Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, have also garnered attention for their unique ability to interact with environmental contaminants, including radiation. Certain species of fungi, such as those in the genus *Radiomyces* and *Cladosporium*, have been observed to absorb and accumulate radioactive isotopes like cesium-137 and strontium-90 from their surroundings. This phenomenon, known as mycoremediation, leverages mushrooms' natural processes to mitigate radiation in contaminated soils. Research suggests that mushrooms can bind radioactive particles within their biomass, effectively reducing their bioavailability and potential harm to ecosystems. While this capability holds promise for environmental cleanup, particularly in areas affected by nuclear accidents, further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms and long-term implications of using mushrooms for radiation absorption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ability to Absorb Radiation | Yes, certain mushroom species can absorb and accumulate radioactive isotopes from their environment. |

| Mechanism | Mushrooms absorb radiation through their mycelium, which acts as a natural filter, binding to radioactive particles like cesium-137 and strontium-90. |

| Species Known for Absorption | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum), and Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) are among the most studied for their radiation-absorbing properties. |

| Applications | Used in mycoremediation to clean up radioactive contaminated soil and water. Also studied for potential use in reducing radiation exposure in humans. |

| Effectiveness | Can reduce radioactive isotopes in soil by up to 90% in some cases, depending on the species and contamination level. |

| Limitations | Absorbed radiation remains in the mushroom biomass, requiring safe disposal. Not a complete solution for large-scale nuclear contamination. |

| Research Status | Active research ongoing, particularly in areas affected by nuclear disasters like Chernobyl and Fukushima. |

| Environmental Impact | Considered an eco-friendly method compared to chemical or physical remediation techniques. |

| Human Consumption | Mushrooms grown in contaminated areas should not be consumed due to accumulated radiation. |

| Future Potential | Promising for localized cleanup efforts and complementary strategies in radiation management. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushroom species with radiation absorption capabilities

Certain mushroom species have demonstrated a remarkable ability to absorb and accumulate radioactive isotopes from their environment, a phenomenon that has intrigued scientists and environmentalists alike. One such species is the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which has been studied extensively for its bioremediation potential. Research conducted in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone revealed that oyster mushrooms can accumulate significant amounts of cesium-137, a radioactive isotope released during nuclear accidents. This capability is attributed to the mushrooms' efficient mycelial networks, which act as natural filters, trapping and concentrating radioactive particles from contaminated soil. For instance, studies have shown that oyster mushrooms can reduce cesium-137 levels in soil by up to 50% within a few weeks, making them a promising tool for decontaminating areas affected by nuclear disasters.

Another notable species is the shiitake mushroom (*Lentinula edodes*), which has been investigated for its ability to absorb strontium-90, another harmful radioactive isotope. In laboratory experiments, shiitake mycelium was exposed to strontium-90-contaminated water, and results indicated that the mushrooms could accumulate the isotope in their fruiting bodies. This process, known as bioaccumulation, effectively removes strontium-90 from the water, rendering it safer for consumption or agricultural use. However, it is crucial to note that mushrooms used for bioremediation should not be consumed, as the accumulated isotopes can pose health risks if ingested. Instead, these mushrooms are typically disposed of safely, often through controlled incineration to prevent further contamination.

The reishi mushroom (*Ganoderma lucidum*), often referred to as the "mushroom of immortality," has also shown potential in radiation absorption studies. Unlike oyster and shiitake mushrooms, reishi's primary role is not in bioremediation but in protecting living organisms from radiation damage. Research suggests that reishi extracts contain compounds like polysaccharides and triterpenes, which exhibit radioprotective properties. For example, animal studies have demonstrated that reishi supplementation can mitigate radiation-induced DNA damage and enhance survival rates in irradiated subjects. While reishi mushrooms themselves do not absorb radiation from the environment, their bioactive components offer a unique approach to combating the harmful effects of radiation exposure.

Practical applications of these mushroom species require careful consideration of environmental conditions and safety protocols. For instance, when using oyster mushrooms for soil decontamination, it is essential to monitor the pH and nutrient levels of the substrate, as these factors influence the mushrooms' growth and absorption efficiency. Additionally, workers handling contaminated mushrooms must wear protective gear to avoid exposure to radioactive isotopes. For those interested in harnessing the radioprotective benefits of reishi, it is advisable to consult healthcare professionals, especially for individuals undergoing radiation therapy or living in high-radiation areas. While mushrooms offer innovative solutions to radiation-related challenges, their use must be guided by scientific rigor and safety precautions.

Mushrooms and Aggression: Unraveling the Myth of Violent Fungal Effects

You may want to see also

Mechanisms of radiation absorption in fungi

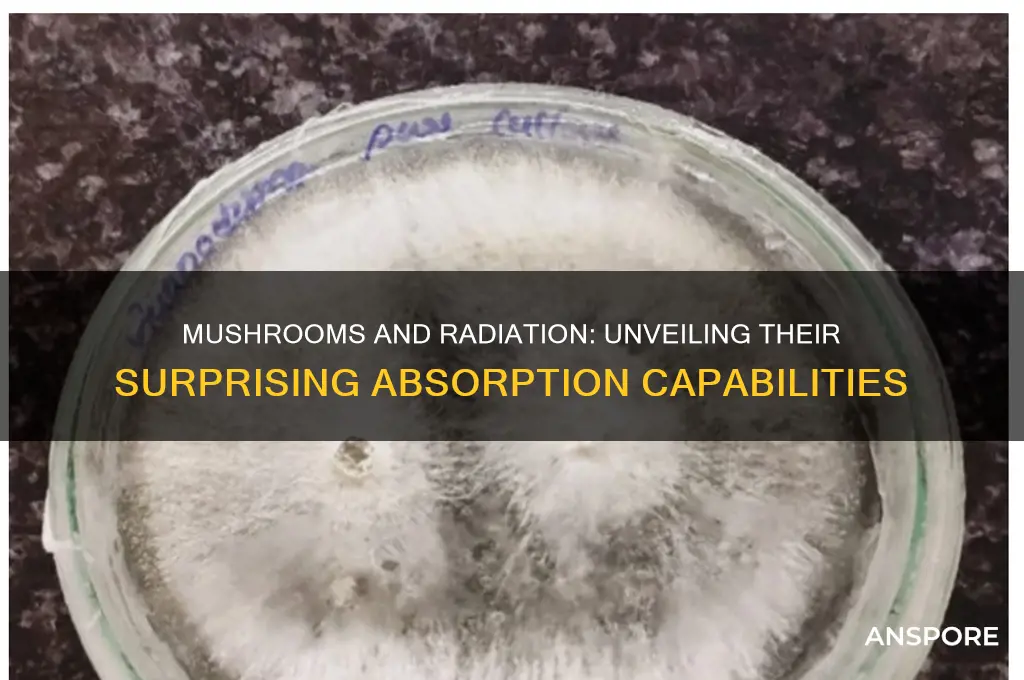

Fungi, particularly mushrooms, possess unique biological mechanisms that enable them to absorb and accumulate radiation, a phenomenon that has intrigued scientists for decades. One key mechanism involves the high melanin content in certain fungal species. Melanin, a pigment found in mushroom cell walls, acts as a natural radioprotective compound. When exposed to ionizing radiation, melanin converts the energy into heat, reducing the formation of harmful free radicals. This process not only protects the fungi but also allows them to thrive in radiation-rich environments, such as the Chernobyl exclusion zone, where melanin-rich fungi like *Cladosporium sphaerospermum* have been observed to flourish.

Another critical mechanism is the fungi’s ability to bioaccumulate radioactive isotopes through their mycelial networks. Mycelium, the root-like structure of fungi, secretes enzymes and acids that break down minerals and metals in the soil, including radioactive particles like cesium-137 and strontium-90. This bioaccumulation process is particularly efficient in species like *Reishi* (*Ganoderma lucidum*) and *Oyster* mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). For instance, studies have shown that *Oyster* mushrooms can reduce soil cesium-137 levels by up to 50% within weeks, making them valuable for bioremediation efforts in contaminated areas. However, this ability also raises concerns about their safety for consumption, as accumulated isotopes can pose health risks if ingested.

A lesser-known mechanism involves the role of fungal antioxidants in mitigating radiation damage. Mushrooms are rich in antioxidants like ergothioneine and glutathione, which neutralize oxidative stress caused by radiation exposure. These compounds not only protect the fungi but also offer potential therapeutic benefits for humans. For example, ergothioneine has been studied for its radioprotective effects in medical settings, particularly in reducing tissue damage during radiation therapy. Incorporating mushrooms like *Shiitake* (*Lentinula edodes*) or *Maitake* (*Grifola frondosa*) into the diet may enhance the body’s resilience to radiation, though dosages should be carefully monitored to avoid overexposure to accumulated isotopes.

Finally, the structural composition of fungal cell walls plays a pivotal role in radiation absorption. Composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides, these cell walls act as a physical barrier and a binding site for radioactive particles. This dual function allows fungi to sequester radiation while maintaining cellular integrity. Practical applications of this mechanism include using fungal biomass as a biofilter in nuclear waste management. For instance, mycelium mats have been employed to filter radioactive isotopes from water, demonstrating their potential as a low-cost, eco-friendly solution. However, implementing such methods requires careful consideration of fungal species and environmental conditions to ensure effectiveness and safety.

Growing Magic Mushrooms from Dried Spores: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Role of melanin in mushroom radiation protection

Melanin, the pigment responsible for color in many organisms, plays a pivotal role in the radiation-absorbing capabilities of certain mushrooms. Unlike humans, where melanin primarily protects against UV radiation, fungal melanin acts as a broad-spectrum radiation shield. Studies have shown that melanized fungi, such as *Cryptococcus neoformans* and *Cladosporium sphaerospermum*, can withstand doses of ionizing radiation up to 10,000 gray (Gy), far exceeding the lethal dose for humans (4–10 Gy). This remarkable resilience is attributed to melanin’s ability to quench reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by radiation, preventing cellular damage.

To harness this property, researchers have explored using melanin-rich mushrooms in bioremediation of radioactive sites. For instance, *C. neoformans* has been tested in Chernobyl’s Exclusion Zone, where it demonstrated the capacity to bind and stabilize radioactive isotopes like cesium-137. Practical applications include incorporating mushroom melanin into protective materials for astronauts or nuclear workers. A 2019 study found that a 1-millimeter layer of melanin-infused polymer reduced gamma radiation exposure by 30%, offering a lightweight alternative to traditional lead shielding.

However, not all mushrooms are created equal in this regard. Melanin content varies widely among species, with darker varieties like *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake) and *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) exhibiting higher protective potential. For home growers or foragers, cultivating or selecting these species could provide a natural radiation shield in contaminated environments. A simple tip: expose mushroom mycelium to UV light during growth, as this stimulates melanin production, enhancing their protective properties.

Despite its promise, mushroom melanin is not a panacea. Its effectiveness depends on radiation type, dosage, and exposure duration. For instance, while melanin excels at neutralizing gamma rays, it is less effective against neutron radiation. Additionally, consuming melanin-rich mushrooms does not confer internal radiation protection; their utility lies in external applications or environmental remediation. As research advances, understanding melanin’s mechanisms could unlock innovative solutions for radiation safety, blending biology with technology.

Mushrooms in Beehives: Benefits, Risks, and Safe Practices Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Potential applications in nuclear cleanup

Mushrooms have demonstrated a unique ability to absorb and accumulate heavy metals and radionuclides from their environment, a process known as bioaccumulation. This characteristic has sparked interest in their potential use for nuclear cleanup, particularly in areas contaminated by radioactive isotopes like cesium-137 and strontium-90. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) have been studied for their efficiency in absorbing cesium, reducing soil contamination levels by up to 50% in controlled experiments. Such findings suggest that fungi could serve as a cost-effective, eco-friendly alternative to traditional remediation methods, which often involve excavation and disposal of contaminated soil.

Implementing mushroom-based cleanup requires careful planning and execution. The process typically involves cultivating mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus—directly in contaminated soil. Mycelium acts as a natural filter, binding to radioactive particles and preventing their spread. For optimal results, select mushroom species with high bioaccumulation rates, such as *Pleurotus ostreatus* or *Lentinula edodes*. After cultivation, the mushrooms must be harvested and safely disposed of, as they will contain concentrated radioactive material. This method is particularly promising for low- to medium-level contamination scenarios, where it can complement other remediation techniques.

One of the most compelling advantages of using mushrooms for nuclear cleanup is their sustainability. Unlike chemical or mechanical methods, fungi rely on natural biological processes, minimizing environmental disruption. Additionally, mushrooms can break down organic pollutants, offering dual benefits in areas with mixed contamination. However, challenges remain, including the need for long-term monitoring to ensure effectiveness and the potential risk of mushrooms re-releasing radionuclides if not properly managed. Research is ongoing to address these concerns, with scientists exploring genetic modifications to enhance fungi’s absorption capabilities and containment strategies.

Comparing mushroom-based cleanup to traditional methods highlights its potential and limitations. Conventional techniques like soil washing or phytoremediation (using plants) are well-established but often expensive and resource-intensive. Mushrooms, on the other hand, can be cultivated with minimal inputs and thrive in a variety of conditions, making them accessible for use in remote or resource-limited areas. However, their slower remediation timeline—often spanning months or years—means they may not be suitable for urgent cleanup efforts. Combining mushroom remediation with other methods could offer a balanced approach, leveraging the strengths of each technique.

For communities affected by nuclear accidents or industrial contamination, mushroom-based cleanup represents a beacon of hope. Pilot projects in Chernobyl and Fukushima have already demonstrated the feasibility of this approach, with local species being cultivated to reduce radiation levels in affected areas. To replicate such efforts, stakeholders should start by identifying native mushroom species with bioaccumulation potential, conducting small-scale trials, and engaging local populations in the process. While not a silver bullet, this innovative use of fungi offers a promising tool in the fight against nuclear contamination, blending science and nature to restore damaged ecosystems.

Can Giant African Land Snails Safely Eat Mushrooms? A Guide

You may want to see also

Impact of radiation on mushroom growth and survival

Mushrooms, particularly certain species like *Reishi* (*Ganoderma lucidum*) and *Oyster* (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), have demonstrated the ability to absorb and accumulate radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137 and strontium-90 from contaminated environments. This phenomenon, known as bioremediation, raises questions about how radiation exposure impacts their growth and survival. While mushrooms can tolerate low to moderate radiation levels, their response varies significantly depending on the dosage, duration, and species. For instance, exposure to gamma radiation below 100 Gy can stimulate mycelial growth in some species due to hormesis, a beneficial low-dose stress response. However, doses exceeding 500 Gy typically inhibit growth, cause cellular damage, and reduce spore viability, highlighting a threshold beyond which radiation becomes detrimental.

To understand the practical implications, consider the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear disasters, where mushrooms became hyperaccumulators of radioactive particles. In these cases, radiation exposure altered mushroom morphology, reduced fruiting body production, and increased mutation rates. For cultivators or foragers, this means that mushrooms from contaminated areas may appear stunted, discolored, or malformed, signaling potential radiation damage. Testing for radionuclide levels using a Geiger-Müller counter or laboratory analysis is crucial before consumption, as accumulated isotopes can pose health risks. For example, cesium-137 mimics potassium in the body, leading to bioaccumulation in vital organs.

From a survival perspective, mushrooms’ ability to absorb radiation is a double-edged sword. While they can help decontaminate soil, their consumption in radioactive environments can transfer harmful isotopes to humans and animals. Species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* have been studied for their role in mycoremediation, breaking down organic pollutants and binding heavy metals, but their efficacy diminishes under high radiation stress. For those in affected areas, cultivating radiation-resistant strains in controlled environments, such as indoor farms with filtered air and soil, can mitigate risks. Additionally, pairing mushrooms with radiation-tolerant plants like sunflowers in phytoremediation projects enhances soil recovery efforts.

Finally, the impact of radiation on mushroom survival extends beyond individual organisms to ecosystem dynamics. Radiation-induced changes in mushroom populations can disrupt nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships with trees, affecting forest health. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi like *Boletus* species, which depend on root associations, may experience reduced colonization rates under radiation stress, impairing tree growth. Conservation efforts in contaminated zones should focus on monitoring fungal biodiversity and promoting species with higher radiation tolerance. By understanding these interactions, we can develop strategies to protect both mushrooms and the ecosystems they support in the face of radiation challenges.

Using Mushroom Stems in Soup: A Tasty, Waste-Free Cooking Tip

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, certain mushrooms, such as *Reishi* (*Ganoderma lucidum*) and *Oyster* (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), have been studied for their ability to absorb and accumulate radioactive isotopes like cesium-137 and strontium-90 from their environment.

Mushrooms absorb radiation through a process called bioaccumulation, where they take up radioactive particles from contaminated soil or water. Some species also produce melanin, a pigment that may bind to radioactive isotopes and reduce their mobility.

Yes, a technique called mycoremediation uses mushrooms to absorb and reduce radioactive contamination in the environment. For example, *Pleurotus ostreatus* has been used to clean up areas affected by nuclear accidents, though it is not a complete solution and requires further research.