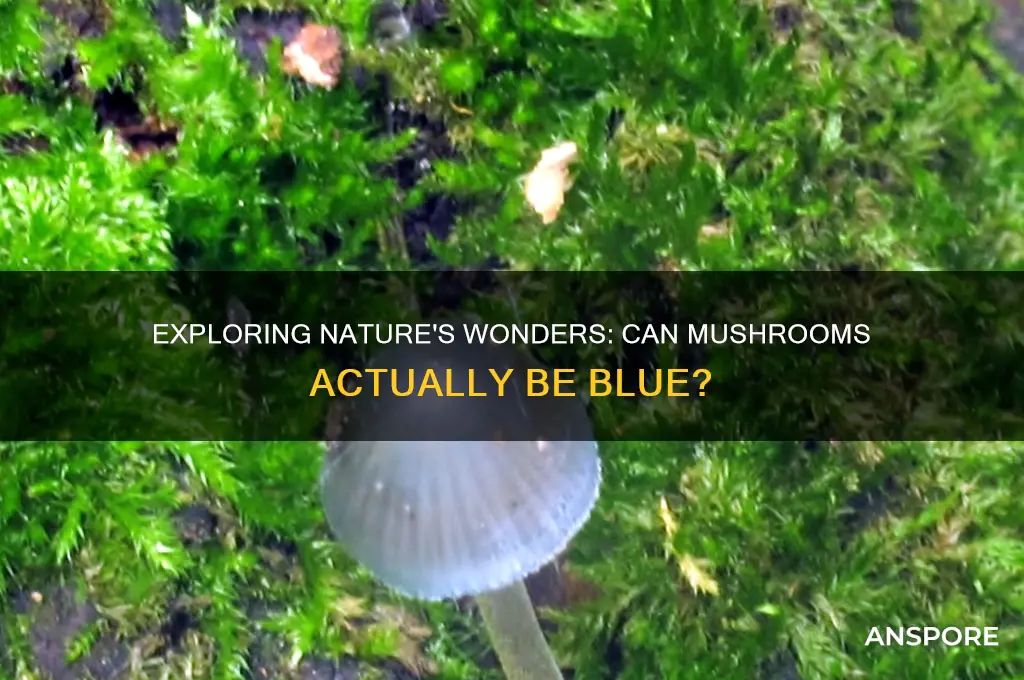

Mushrooms, often associated with earthy browns and whites, can indeed exhibit a striking blue hue, captivating both foragers and mycologists alike. This unusual coloration is primarily due to the presence of specific pigments or chemical reactions within the mushroom's tissues. For instance, the Indigo Milk Cap (*Lactarius indigo*) is renowned for its vibrant blue cap and gills, while the Blue Entoloma (*Entoloma hochstetteri*) boasts a stunning azure appearance. These blue mushrooms are not only visually intriguing but also highlight the diverse and often surprising characteristics of the fungal kingdom, sparking curiosity about their ecological roles, edibility, and the biochemical processes behind their unique colors.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Mushrooms Be Blue? | Yes, some mushrooms can naturally exhibit blue coloration. |

| Common Blue Mushroom Species | Indigo Milk Cap (Lactarius indigo), Blue Entoloma (Entoloma hochstetteri), Blue Roundhead (Stropharia caerulea). |

| Cause of Blue Color | Often due to pigments like azulene or other blue-producing compounds in the mushroom's tissue. |

| Toxicity | Varies by species; some blue mushrooms are edible (e.g., Indigo Milk Cap), while others are toxic. Always verify before consuming. |

| Habitat | Found in forests, woodlands, and grassy areas, depending on the species. |

| Seasonality | Typically appear in late summer to fall, depending on the species and region. |

| Ecological Role | Many blue mushrooms are mycorrhizal, forming symbiotic relationships with trees, or saprotrophic, decomposing organic matter. |

| Cultural Significance | Some blue mushrooms are prized in culinary traditions, while others are admired for their striking appearance in nature. |

| Conservation Status | Varies; some species are common, while others may be rare or threatened due to habitat loss. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Blue Mushrooms: Explore species like Indigo Milk Cap and Blue Entoloma found in forests

- Causes of Blue Color: Pigments, bruising reactions, or mycelium chemistry create blue hues in mushrooms

- Edibility of Blue Mushrooms: Some are edible, others toxic; proper identification is crucial for safety

- Cultivation of Blue Mushrooms: Techniques to grow blue varieties at home or in labs

- Myths About Blue Mushrooms: Debunking folklore and misconceptions surrounding blue-colored fungi

Natural Blue Mushrooms: Explore species like Indigo Milk Cap and Blue Entoloma found in forests

Blue mushrooms exist in nature, and their vibrant hues are not just a feast for the eyes but also a fascinating subject for mycologists and nature enthusiasts alike. Among the most striking examples are the Indigo Milk Cap (*Lactarius indigo*) and the Blue Entoloma (*Entoloma hochstetteri*). These species, found in forests across North America, Europe, and New Zealand, challenge the typical brown and white mushroom stereotypes. The Indigo Milk Cap, for instance, boasts a deep blue cap and stem, while its latex—a milky substance exuded when injured—is also indigo. This unique feature makes it easily identifiable, even for novice foragers. However, caution is advised: while it is edible and used in culinary traditions, proper preparation is essential to avoid its mild acridity.

In contrast, the Blue Entoloma is a visual marvel but a culinary no-go. Found in New Zealand’s forests, this mushroom’s electric blue color is a result of its unique cellular structure, not pigments. Despite its allure, it is toxic and should never be consumed. Its presence highlights the duality of nature’s beauty and danger, serving as a reminder that not all colorful mushrooms are safe. Foraging enthusiasts should always carry a reliable field guide and consult experts when in doubt, as misidentification can have serious consequences.

Exploring these species in their natural habitats offers more than just aesthetic pleasure. The Indigo Milk Cap, for example, plays a role in forest ecosystems by forming mycorrhizal relationships with trees, aiding nutrient exchange. Its blue latex is thought to deter predators, though research is ongoing. The Blue Entoloma, on the other hand, remains a mystery in terms of ecological function, but its striking appearance has made it a symbol of New Zealand’s biodiversity. Both mushrooms underscore the importance of conservation efforts to protect their forest habitats, which are increasingly threatened by deforestation and climate change.

For those interested in observing these species, timing and location are key. The Indigo Milk Cap thrives in coniferous and deciduous forests during late summer and fall, often found near oak and beech trees. The Blue Entoloma prefers New Zealand’s native forests, particularly those with beech trees, and is most visible in spring. When venturing out, wear appropriate gear, carry a knife for clean cuts, and avoid disturbing the forest floor. Photography is a great way to document your findings without harming the mushrooms or their ecosystems.

In conclusion, natural blue mushrooms like the Indigo Milk Cap and Blue Entoloma are not only visually stunning but also ecologically significant. While one offers culinary potential with proper preparation, the other serves as a cautionary tale of nature’s beauty and danger. By understanding and respecting these species, we can appreciate their role in the forest while ensuring their preservation for future generations. Whether you’re a forager, photographer, or nature lover, these blue wonders are a testament to the diversity and intrigue of the fungal kingdom.

Enhance Your Curry with Mushrooms: Tips and Flavorful Ideas

You may want to see also

Causes of Blue Color: Pigments, bruising reactions, or mycelium chemistry create blue hues in mushrooms

Mushrooms can indeed be blue, and this striking color often stems from specific pigments, bruising reactions, or unique mycelium chemistry. One of the most well-known blue mushrooms is the *Lactarius indigo*, which owes its vibrant hue to a water-soluble pigment called azulene. Azulene is a compound derived from sesquiterpenes and is also found in chamomile and eucalyptus. Its deep blue color is not just visually captivating but also stable, meaning it doesn’t fade easily when exposed to light or air. This pigment serves as a natural defense mechanism, potentially deterring predators with its unusual appearance.

Bruising reactions are another common cause of blue hues in mushrooms. When certain species, like the *Coprinus comatus* or shaggy mane mushroom, are damaged or handled, their flesh reacts by turning blue. This occurs due to enzymatic browning, a process similar to what happens when an apple is cut and exposed to air. In mushrooms, the enzyme polyphenol oxidase oxidizes phenolic compounds, resulting in a blue or bluish-green discoloration. While this reaction can be alarming, it’s typically harmless and often used as a field identification marker for foragers.

Mycelium chemistry plays a crucial role in blue coloration as well, particularly in species like *Clitocybe nuda* (wood blewit). The mycelium produces a blue pigment as part of its metabolic processes, which accumulates in the fruiting body. This pigment is thought to protect the mushroom from UV radiation or pathogens. Interestingly, the intensity of the blue color can vary based on environmental factors such as soil pH, humidity, and temperature. For cultivators, maintaining optimal growing conditions—such as a pH range of 6.0 to 6.5 and a humidity level of 85–95%—can enhance the blue pigmentation in these species.

Understanding these mechanisms isn’t just academic—it has practical applications. For foragers, recognizing blue pigments or bruising reactions can aid in species identification and safety. For cultivators, manipulating mycelium chemistry can produce mushrooms with more vibrant colors for culinary or decorative purposes. For example, exposing *Lactarius indigo* mycelium to controlled light cycles can intensify its azulene production. Whether you’re a mycologist, forager, or hobbyist, knowing the science behind blue mushrooms unlocks a deeper appreciation for these fascinating organisms.

Legally Buying Magic Mushroom Seeds: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Edibility of Blue Mushrooms: Some are edible, others toxic; proper identification is crucial for safety

Blue mushrooms, with their striking appearance, captivate both foragers and nature enthusiasts. However, their allure comes with a critical caveat: not all blue mushrooms are safe to eat. While some, like the Indigo Milk Cap (Lactarius indigo), are prized for their culinary value, others, such as the Blue-Staining Russula, can cause gastrointestinal distress. The key to safely enjoying these fungi lies in precise identification, as even experienced foragers can mistake toxic species for edible ones. Always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult an expert before consumption.

Proper identification involves examining specific traits: spore color, gill structure, and the presence of bruising or milky sap. For instance, the Indigo Milk Cap exudes a distinctive blue milk-like substance when cut, a unique identifier. In contrast, toxic species often lack such clear markers or may exhibit subtle differences, such as a slightly different shade of blue or a faintly acrid smell. Beginners should avoid blue mushrooms altogether until they gain sufficient knowledge, as misidentification can lead to severe consequences, including organ damage or hospitalization.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to accidental poisoning, as they may be drawn to the vibrant colors of blue mushrooms. If ingestion occurs, seek immediate medical attention, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Dosage matters in toxicity; even a small amount of a toxic blue mushroom can cause symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or dizziness. Prevention is paramount—educate family members about the risks and supervise outdoor activities in mushroom-rich areas.

For those determined to forage, start with guided tours or workshops led by mycologists. Learn to use a spore print kit to determine spore color, a crucial step in identification. Avoid relying solely on color, as environmental factors can alter appearance. Instead, focus on a combination of characteristics, such as habitat, season, and physical features. Remember, the goal is not just to find blue mushrooms but to find the *right* blue mushrooms. Safety should always outweigh curiosity in the wild.

Upside-Down Gardening: Can Mushrooms Thrive in a Topsy Turvy Bag?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cultivation of Blue Mushrooms: Techniques to grow blue varieties at home or in labs

Blue mushrooms, such as the striking *Clitocybe nuda* (wood blewit) or the bioluminescent *Mycena lux-coeli*, captivate both hobbyists and researchers. Cultivating these varieties at home or in labs requires precision, as their pigmentation often ties to specific environmental triggers. Unlike common button mushrooms, blue species demand controlled conditions to express their vivid hues, making their cultivation both an art and a science.

Step-by-Step Cultivation Techniques

Begin by sourcing spores or mycelium from reputable suppliers, ensuring the strain’s authenticity. Sterilize your substrate—a mix of hardwood sawdust, straw, or compost—to prevent contamination. Inoculate the substrate with the mycelium in a sterile environment, maintaining temperatures between 68–72°F (20–22°C). Blue mushrooms often thrive in slightly acidic conditions (pH 5.5–6.0), so adjust your substrate accordingly. Humidity levels should remain above 85%, mimicking their natural woodland habitats. For bioluminescent varieties, introduce low-light conditions during fruiting to enhance glow intensity.

Environmental Triggers for Blue Pigmentation

The blue coloration in mushrooms like *Clitocybe nuda* stems from azulene compounds, influenced by factors like pH, light exposure, and nutrient availability. To intensify blue hues, expose fruiting bodies to indirect natural light for 4–6 hours daily. Avoid direct sunlight, which can bleach pigments. Some cultivators introduce trace amounts of copper sulfate (0.01% solution) to the substrate, though this must be done cautiously to prevent toxicity. Monitor pH levels weekly, using peat moss or citric acid to maintain acidity.

Challenges and Troubleshooting

Contamination is the primary hurdle in blue mushroom cultivation. Always use sterile techniques, such as flame-sterilizing tools and working in a laminar flow hood if possible. If mold appears, remove affected areas immediately and increase air circulation. Slow mycelium growth? Ensure proper nutrient balance—a 2:1 ratio of carbon to nitrogen in the substrate often accelerates colonization. For home growers, investing in a humidity-controlled grow tent can mitigate environmental inconsistencies.

Advanced Techniques for Lab Cultivation

In lab settings, agar cultivation allows for precise control over genetic expression. Transfer spores to malt extract agar plates, incubating at 70°F (21°C) for 7–14 days. Once mycelium colonizes, subculture onto nutrient-rich agar supplemented with azulene-inducing compounds like calcium chloride (0.5% concentration). For research purposes, bioluminescent species like *Mycena lux-coeli* can be genetically modified to enhance glow intensity, though this requires advanced molecular techniques. Document growth conditions meticulously to replicate successful outcomes.

Cultivating blue mushrooms is a rewarding endeavor that bridges horticulture and chemistry. Whether at home or in a lab, understanding the interplay of environmental factors and biochemical triggers unlocks the potential to grow these mesmerizing fungi. With patience and precision, even beginners can witness the ethereal beauty of blue mushrooms flourishing under their care.

Fried Mushrooms for Babies: Safe or Risky Feeding Choice?

You may want to see also

Myths About Blue Mushrooms: Debunking folklore and misconceptions surrounding blue-colored fungi

Blue mushrooms, with their striking appearance, have long captivated human imagination, often becoming the subject of myths and misconceptions. One prevalent myth is that all blue mushrooms are poisonous. While it’s true that some blue fungi, like the indigo milk cap (*Lactarius indigo*), are edible, others, such as the blue-staining species in the *Entoloma* genus, can be toxic. The color itself is not an indicator of toxicity; instead, proper identification based on spore print, habitat, and other characteristics is essential. Blindly avoiding or consuming blue mushrooms based on color alone can lead to dangerous outcomes.

Another common misconception is that blue mushrooms are rare and mystical, often associated with fairy tales or magical properties. While blue fungi are less common than their brown or white counterparts, they are not as rare as folklore suggests. Species like the *Clitocybe nuda* (wood blewit) and *Cortinarius caerulescens* are found in various regions, particularly in temperate forests. Their presence is a natural result of specific pigments, such as azulene or polyporic acid, rather than any supernatural origin. Appreciating their biological uniqueness over mythical narratives fosters a deeper understanding of fungal ecology.

A third myth is that blue mushrooms glow in the dark, a belief fueled by their otherworldly appearance. While bioluminescent fungi do exist, such as the ghost mushroom (*Omphalotus nidiformis*), none of the naturally blue species exhibit this trait. The confusion likely arises from their vivid color, which can appear luminous in certain lighting conditions. To distinguish fact from fiction, examine mushrooms under consistent light and avoid attributing glow-in-the-dark properties without scientific evidence. This clarity helps separate biological reality from imaginative folklore.

Lastly, some believe blue mushrooms possess medicinal or psychedelic properties solely due to their color. While certain fungi, like *Psilocybe* species, can be blue-tinted and psychoactive, color is not a reliable indicator of their effects. Medicinal properties, such as those found in *Lactarius indigo*, are species-specific and not tied to pigmentation. Always consult expert resources or mycologists before consuming any mushroom for medicinal or recreational purposes. Relying on color alone can lead to misidentification and potential harm.

In summary, blue mushrooms are fascinating organisms that defy simplistic myths. By understanding their biology, distribution, and properties, we can appreciate them for what they truly are—remarkable examples of nature’s diversity. Avoid folklore-driven assumptions and prioritize factual knowledge to safely engage with these captivating fungi.

Sleeping on Mushrooms: Safe, Risky, or Just a Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some mushrooms can naturally be blue due to pigments like azulene or other compounds that produce blue hues.

Not all blue mushrooms are safe to eat. Some are edible, like the Indigo Milk Cap, while others, like the Blue Entoloma, are toxic. Always identify mushrooms properly before consuming.

Some mushrooms, like the Psilocybe species, contain psilocin or psilocybin, which oxidize when exposed to air, causing them to turn blue when bruised or damaged.

Blue mushrooms are relatively rare compared to brown, white, or red varieties, but they can be found in specific habitats, particularly in forests with certain tree species.

Some blue mushrooms, like those containing psilocybin, are being studied for their potential medicinal uses, including treating depression and anxiety. However, their use is highly regulated and should only be under professional guidance.