The question of whether mushrooms, particularly psychedelic varieties like psilocybin mushrooms, can be detected in a urine analysis (UA) is a topic of interest for both medical professionals and individuals undergoing drug testing. While standard UAs typically screen for common substances such as marijuana, cocaine, opioids, and amphetamines, the detection of psilocybin and its metabolites is less straightforward. Psilocybin is metabolized quickly in the body, with its primary metabolite, psilocin, having a short detection window of approximately 24–48 hours in urine. Specialized tests are required to identify these compounds, and they are not included in routine drug panels. As a result, mushrooms are unlikely to be detected in a standard UA unless specifically tested for, making this an important consideration for both testing protocols and individuals concerned about potential detection.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Detection in Standard Urine Analysis (UA) | Mushrooms (psilocybin mushrooms) are not typically detected in a standard urine analysis (UA). Standard UAs are designed to detect common substances like drugs of abuse (e.g., opioids, cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines), alcohol, and certain metabolites, but not psilocybin or psilocin (the active compounds in mushrooms). |

| Specialized Testing Required | Detection of psilocybin or psilocin requires specific, targeted tests not included in routine UAs. These tests are rarely performed unless specifically requested. |

| Detection Window | If specialized testing is conducted, psilocybin and its metabolites can be detected in urine for up to 24-48 hours after ingestion, depending on factors like dosage, metabolism, and frequency of use. |

| False Positives/Negatives | Standard UAs do not cross-react with psilocybin, so false positives are unlikely. However, specialized tests may have limitations in accuracy. |

| Legal and Medical Context | Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal in many jurisdictions, but their detection in a UA is uncommon unless specifically tested for, often in forensic or research settings. |

| Other Detection Methods | Hair, blood, or saliva tests can also detect psilocybin, but these are even less common than urine testing. |

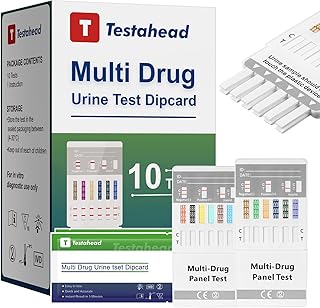

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Types of mushrooms detectable in UA tests

Standard urine analysis (UA) tests are not designed to detect mushrooms or their psychoactive compounds. These tests typically screen for substances like THC, opioids, amphetamines, and alcohol metabolites. However, certain mushrooms, particularly those containing psilocybin, can produce metabolites that may be detectable in specialized drug tests, though not in routine UAs. Psilocybin, the primary psychoactive compound in "magic mushrooms," is metabolized into psilocin, which can be identified in urine, blood, or hair samples using specific assays.

Forensic toxicology labs employ advanced techniques like liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to detect psilocin in urine samples. The detection window for psilocin is relatively short, typically 24–48 hours after ingestion, depending on dosage and individual metabolism. A moderate dose of 1–2 grams of dried psilocybin mushrooms can produce detectable levels of psilocin in urine for up to 24 hours. However, these tests are not part of standard UA panels and are only used in specific contexts, such as clinical research or legal investigations.

Amanita mushrooms, another class of fungi containing compounds like ibotenic acid and muscimol, are even less likely to be detected in UAs. These compounds are structurally distinct from those screened in routine drug tests and require specialized assays for identification. While muscimol can be detected in urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), such testing is rare and typically reserved for poisoning cases or research purposes. For individuals concerned about detection, it’s crucial to understand that standard UAs will not flag these substances unless specifically tested for.

In practical terms, if you’re undergoing a routine UA for employment or medical purposes, mushrooms—whether psilocybin-containing or Amanita species—will not be detected. However, if you’re participating in a clinical trial or facing legal scrutiny, specialized testing could reveal mushroom metabolites. To minimize detection risks, abstaining from mushroom use for at least 72 hours before testing is advisable, as this allows most metabolites to clear the system. Always verify the scope of testing if you suspect specialized assays might be used.

Do Psychedelic Mushrooms Show Up in Standard Drug Tests?

You may want to see also

False positives linked to mushroom consumption

Mushroom consumption, particularly of certain wild varieties, has been linked to false positives in urine drug tests, raising concerns for both consumers and employers. Psilocybin-containing mushrooms, often referred to as "magic mushrooms," are a prime example. When metabolized, psilocybin breaks down into psilocin, which can cross-react with immunoassay tests commonly used in initial drug screenings. These tests are designed to detect substances like LSD or other hallucinogens, but their broad reactivity can lead to misleading results. A study published in the *Journal of Analytical Toxicology* highlighted that even moderate consumption (1-2 grams) of psilocybin mushrooms can trigger false positives for up to 48 hours post-ingestion, depending on the individual’s metabolism and the test’s cutoff threshold.

To mitigate the risk of false positives, it’s crucial to understand the limitations of urine drug tests. Confirmatory tests, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), are far more accurate and can differentiate between psilocin and other substances. However, these tests are rarely conducted unless an initial screening flags a positive result. For individuals who consume mushrooms recreationally or for therapeutic purposes, disclosing recent mushroom use to the testing authority can preemptively address potential discrepancies. Employers and testing facilities should also be aware of this cross-reactivity to avoid unfair consequences for employees or applicants.

Another factor contributing to false positives is the presence of naturally occurring compounds in mushrooms that mimic illicit substances. For instance, some edible mushrooms contain trace amounts of ibotenic acid or muscarine, which can theoretically interfere with drug tests designed to detect stimulants or opioids. While these compounds are not psychoactive in typical culinary doses, their structural similarity to controlled substances can lead to confusion. A 2019 case report in *Forensic Science International* documented a false positive for opioids in a patient who had consumed a large quantity of wild mushrooms, underscoring the need for context-aware testing protocols.

Practical steps can be taken to minimize the likelihood of false positives. For individuals anticipating a drug test, avoiding mushroom consumption for at least 72 hours beforehand is advisable, as this allows sufficient time for metabolites to clear the system. Staying hydrated and maintaining a balanced diet can also support faster detoxification. If a false positive occurs, requesting a confirmatory test and providing documentation of mushroom consumption (e.g., receipts from a grocery store or a statement from a healthcare provider) can help resolve the issue. Awareness and proactive communication are key to navigating this potential pitfall.

In conclusion, while mushrooms themselves are not typically targeted in urine drug tests, their chemical components can inadvertently trigger false positives. Understanding the mechanisms behind these results and taking preventive measures can help individuals and organizations avoid unnecessary complications. As drug testing technology evolves, greater specificity in detecting substances will reduce the incidence of such errors, but until then, vigilance and education remain essential.

Are Year-Old Canned Mushrooms Safe to Eat? Expert Advice

You may want to see also

Detection window for mushroom metabolites

Mushroom metabolites, particularly those from psilocybin-containing species, can be detected in urine, but the window of detection varies significantly based on factors like dosage, metabolism, and testing methodology. Psilocin, the active metabolite of psilocybin, is typically detectable in urine for 24 to 48 hours after ingestion. However, more sensitive tests, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), can extend this window to up to 72 hours, especially with higher doses (e.g., 2–3 grams of dried mushrooms). For occasional users, a standard urine test is unlikely to detect metabolites beyond this timeframe, but chronic or heavy use may leave traceable residues for slightly longer due to cumulative buildup.

Understanding the detection window requires considering individual metabolic rates, which differ based on age, weight, hydration, and liver function. Younger individuals with faster metabolisms may eliminate psilocin more quickly, reducing the detection window to as little as 12 hours in some cases. Conversely, older adults or those with impaired liver function may retain metabolites longer, potentially extending detection to 48–72 hours. Hydration plays a critical role; drinking water can dilute urine and expedite excretion, but excessive fluid intake may trigger test rejections due to sample adulteration. For accurate results, follow standard pre-test instructions and avoid overhydration.

Employing strategies to minimize detection is a common concern, but few methods are reliable. Detox drinks or diuretics may temporarily dilute urine but do not guarantee metabolite elimination. Time remains the most effective factor in clearing psilocin from the system. For individuals facing drug testing, abstaining from mushroom use for at least 72 hours is advisable, with a full week recommended for higher doses or chronic use. Home testing kits can provide preliminary confirmation of clearance but are less sensitive than laboratory tests, so negative home results do not ensure a negative lab result.

Comparatively, mushroom metabolites have a shorter detection window than substances like cannabis or opioids, which can remain traceable in urine for days to weeks. This brevity is due to psilocin’s rapid metabolism and excretion, making it less likely to be detected in routine screenings. However, specialized tests designed for hallucinogens can still identify metabolites within the 24–72 hour window, particularly in forensic or clinical contexts. Awareness of these timelines is crucial for individuals in professions requiring drug testing, as even legal mushroom use in certain regions may trigger positive results in zero-tolerance environments.

In practical terms, the detection window for mushroom metabolites is narrow but non-negotiable. For a standard urine test, plan for at least 48 hours of abstinence, with an additional buffer for higher doses or metabolic variability. Employers or testing agencies rarely disclose the specific substances screened, so assuming mushrooms could be included is prudent. While the legal status of psilocybin varies, its detectability remains consistent across testing protocols. Prioritize transparency with testing authorities if mushroom use is a concern, as disclosure may mitigate consequences compared to an unexpected positive result.

Baking Portobello Mushrooms: Tips, Recipes, and Perfect Techniques

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common mushrooms that may flag UA tests

Certain mushrooms, particularly those containing psychoactive compounds, can trigger false positives on urine analysis (UA) tests. Psilocybin mushrooms, for instance, contain psilocybin and psilocin, which metabolize into compounds that may cross-react with immunoassays used in drug screenings. While these tests are not designed to detect psilocybin, the structural similarity to LSD or other indole alkaloids can lead to misleading results. A study published in the *Journal of Analytical Toxicology* highlights that psilocybin can cause false positives for LSD or serotonin, though confirmatory tests like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) can differentiate these substances.

Another mushroom of concern is the Amanita muscaria, known for its ibotenic acid and muscimol content. These compounds are not typically screened for in standard UAs but can theoretically produce false positives for sedatives or benzodiazepines due to their depressant effects. However, such cross-reactivity is rare and usually requires high doses or repeated consumption. For example, ingesting more than 10 grams of dried Amanita muscaria could increase the likelihood of metabolic byproducts interfering with test results, though this is not well-documented in clinical settings.

Reishi mushrooms (Ganoderma lucidum), often used in traditional medicine, contain triterpenes that may interfere with drug tests, particularly those screening for opioids. While triterpenes are not opioids, their complex molecular structure could potentially trigger false positives in initial immunoassays. A 2019 case report in *Clinical Toxicology* described a patient who tested positive for opioids after consuming reishi supplements, though GC-MS confirmed no opioid presence. This underscores the importance of confirmatory testing when using supplements derived from mushrooms.

To minimize the risk of false positives, individuals should disclose mushroom consumption to testing authorities, especially if using psychoactive or medicinal varieties. For example, psilocybin users should abstain for at least 72 hours before a UA, as metabolites can persist in urine for 24–48 hours after ingestion. Similarly, those taking reishi or Amanita-based supplements should provide documentation of their regimen to avoid misinterpretation. While mushrooms are not primary targets of UAs, their biochemical complexity demands caution in testing scenarios.

Magic Mushrooms' Impact: Rewiring the Brain and Transforming Perception

You may want to see also

Differentiating mushroom compounds from illicit substances

Mushroom compounds, particularly psilocybin, present a unique challenge in drug testing due to their distinct metabolic pathways and chemical structures. Unlike illicit substances such as cocaine or opioids, psilocybin is rapidly metabolized into psilocin, which is then broken down into inactive compounds. This process significantly reduces the detection window in standard urine analysis (UA), typically limiting it to 24–48 hours after ingestion. In contrast, substances like THC or amphetamines can remain detectable for days or even weeks, depending on dosage and frequency of use. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate interpretation of UA results, especially in contexts where mushroom use may be legally or medically relevant.

To differentiate mushroom compounds from illicit substances in a UA, laboratories must employ specific testing methodologies. Standard drug panels often do not include psilocybin or psilocin, as they are not classified as drugs of abuse in many jurisdictions. However, specialized tests, such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), can detect these compounds with high sensitivity. For instance, a dose of 10–20 mg of psilocybin can be detected in urine within 3–6 hours post-ingestion, but levels drop rapidly thereafter. In comparison, a single dose of cocaine (50–100 mg) may remain detectable for up to 72 hours. This highlights the need for targeted testing protocols when mushroom use is suspected, particularly in forensic or clinical settings.

From a practical standpoint, differentiating mushroom compounds from illicit substances requires clear communication between testers and individuals being screened. For example, in workplace drug testing, employees should be informed that standard UAs may not detect mushrooms, but specialized tests can be requested if there is a specific concern. Similarly, in medical settings, patients should disclose mushroom use to avoid misinterpretation of symptoms or test results. For instance, psilocybin’s psychoactive effects can mimic those of illicit substances, but its therapeutic use in treating conditions like depression or PTSD necessitates a nuanced approach to testing and interpretation.

A comparative analysis reveals that the legal and medical contexts of mushroom use further complicate differentiation efforts. In jurisdictions where psilocybin is decriminalized or approved for therapeutic use, such as Oregon or certain European countries, its detection in a UA may not carry the same implications as illicit substances. Conversely, in regions where it remains illegal, positive results could lead to legal or occupational consequences. This underscores the importance of aligning testing practices with local regulations and medical guidelines. For example, a 25-year-old patient in a clinical trial for psilocybin-assisted therapy should not face penalties for a positive UA, whereas an airline pilot in a zero-tolerance jurisdiction might.

In conclusion, differentiating mushroom compounds from illicit substances in a UA demands a combination of specialized testing, clear communication, and context-aware interpretation. By understanding the unique metabolic profile of psilocybin and employing targeted methodologies like LC-MS/MS, laboratories can provide accurate results that reflect the distinct nature of mushroom use. Practical tips, such as disclosing use in medical settings and staying informed about local regulations, further ensure that testing outcomes are both fair and meaningful. This approach not only enhances the reliability of UAs but also acknowledges the evolving role of mushrooms in medicine and society.

Do Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Expire? Shelf Life and Safety Concerns

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, standard UAs typically test for drugs like marijuana, cocaine, opioids, and amphetamines, not mushrooms or psilocybin.

Psilocybin can be detected in specialized drug tests, but it is not included in standard UAs unless specifically requested.

Psilocybin is usually undetectable in urine after 24-48 hours, but this can vary based on metabolism and dosage.

No, consuming mushrooms (psilocybin or edible varieties) will not cause a false positive on a standard UA for common drugs.

Yes, specialized tests can detect psilocybin, but they are not part of routine UAs and must be specifically ordered.

![[5 pack] Prime Screen 14 Panel Urine Drug Test Cup - Instant Testing Marijuana (THC),OPI,AMP, BAR, BUP, BZO, COC, mAMP, MDMA, MTD, OXY, PCP, PPX, TCA](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71cI114sLUL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Prime Screen-12 Panel Multi Drug Urine Test Compact Cup (THC 50, AMP,BAR,BUP,BZO,COC,mAMP/MET,MDMA,MOP/OPI,MTD,OXY,PCP) C-Cup-[1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/714z5mLCPkL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Prime Screen Multi-Drug Urine Test Cup 16 Panel Kit (AMP,BAR,BUP,BZO,COC,mAMP,MDMA,MOP/OPI,MTD,OXY,PCP,THC, ETG, FTY, TRA, K2) -[1 Pack]-CDOA-9165EFTK](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/718HvC-tp-L._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Easy@Home 5 Panel Urine Drug Test Kit [5 Pack] - THC/Marijuana, Cocaine, OPI/Opiates, AMP, BZO All Drugs Testing Strips in One Kit - at Home Use Screening Test with Results in 5 Mins #EDOAP-754](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81pqr85M3-L._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![[1 Test Cup] 14-Panel EZCHECK® Multi-Drug Urine Test Cup – at-Home Instant Testing for 14 Substances - Fast Result in 5 mins - FSA/HSA Eligible](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71Geu5JRvZL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Prime Screen [5 Pack] 6 Panel Urine Drug Test Kit (THC-Marijuana, BZO-Benzos, MET-Meth, OPI, AMP, COC), WDOA-264](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71hU5zzuEaL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![[5 Pack] Prime Screen 12 Panel Urine Test (AMP,BAR,BZO,COC,mAMP,MDMA,MOP/OPI 300,MTD,OXY,PCP,TCA,THC) - WDOA-7125](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71Hy719lOfL._AC_UL320_.jpg)