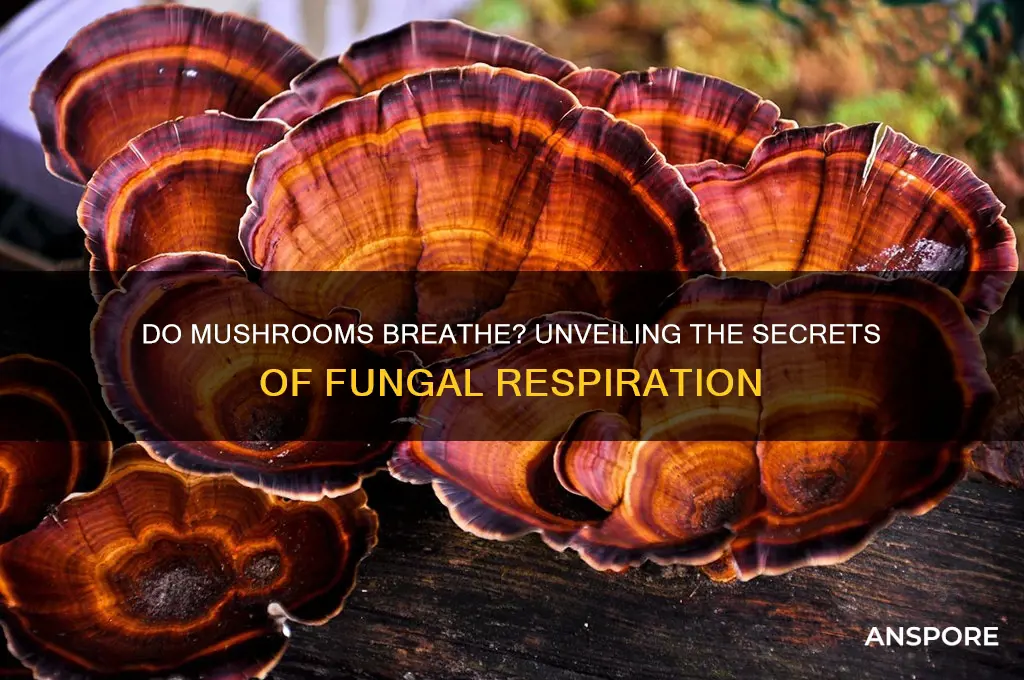

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants, are actually fungi and belong to a separate kingdom of organisms. Unlike plants and animals, mushrooms do not have lungs or a respiratory system, yet they still engage in a form of breathing essential for their survival. This process, known as cellular respiration, allows mushrooms to convert organic matter into energy by exchanging gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide through their porous surfaces. While it differs fundamentally from the breathing mechanisms of animals, this gas exchange is crucial for mushrooms to thrive and play their vital role in ecosystems as decomposers and nutrient recyclers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Mushrooms Breathe? | No, mushrooms do not breathe in the same way animals do. They lack lungs or a respiratory system. |

| Gas Exchange Mechanism | Mushrooms exchange gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide) directly through their cell membranes via diffusion. |

| Oxygen Requirement | Mushrooms require oxygen for cellular respiration, a process that breaks down glucose to release energy. |

| Carbon Dioxide Production | Mushrooms produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct of cellular respiration. |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | Some mushroom species can tolerate low oxygen conditions for short periods. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Do mushrooms have lungs?

Mushrooms, unlike animals, do not possess lungs or any respiratory organs as we understand them. Their method of gas exchange is fundamentally different from that of multicellular organisms with specialized breathing systems. Instead of lungs, mushrooms rely on a process called diffusion to absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide directly through their cell walls. This passive mechanism is sufficient for their metabolic needs, as fungi grow slowly and have low energy requirements compared to animals. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the unique biology of mushrooms and dispelling the misconception that they breathe like humans or other animals.

To illustrate, consider the structure of a mushroom. Its body, or mycelium, consists of a network of thread-like filaments called hyphae. These hyphae are permeable, allowing gases to move freely in and out of the cells. This design eliminates the need for complex respiratory organs. For example, a single cubic inch of soil can contain miles of fungal hyphae, all exchanging gases efficiently without lungs. This simplicity is a testament to the adaptability of fungi, which thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying wood, using minimal resources.

From a practical standpoint, this knowledge has implications for mushroom cultivation. Growers do not need to worry about providing a respiratory system for their fungi; instead, they focus on maintaining optimal humidity, temperature, and substrate conditions. Ensuring proper air circulation in grow rooms or containers is essential, not because mushrooms "breathe" like animals, but because it prevents the buildup of carbon dioxide and promotes healthy mycelial growth. For instance, using fans or vents to circulate air can significantly improve yields in oyster or shiitake mushroom farms.

Comparatively, the absence of lungs in mushrooms highlights the diversity of life’s strategies for survival. While animals evolved complex respiratory systems to support high-energy lifestyles, fungi adopted a minimalist approach, relying on diffusion to meet their needs. This contrast underscores the principle that evolution favors efficiency over complexity when simpler solutions suffice. For educators or enthusiasts, this comparison offers a compelling example of how different organisms solve the same problem—gas exchange—in radically different ways.

In conclusion, mushrooms do not have lungs, nor do they need them. Their reliance on diffusion through permeable cell walls is a highly effective adaptation that supports their growth and metabolism. This fact not only deepens our understanding of fungal biology but also informs practical applications in cultivation and education. By recognizing the unique mechanisms at play, we can better appreciate the ingenuity of nature and apply this knowledge to real-world scenarios, whether in a classroom or a mushroom farm.

Mushrooms and Lactic Bacteria: Exploring Symbiotic Growth Possibilities

You may want to see also

How do mushrooms exchange gases?

Mushrooms, unlike animals, lack lungs or gills for gas exchange, yet they actively participate in respiration. Their unique structure—a network of hyphae forming the mycelium—facilitates this process. Oxygen diffuses directly through the cell walls of these hyphae, while carbon dioxide, a byproduct of metabolism, escapes in the same manner. This passive yet efficient system allows mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying logs.

Consider the analogy of a sponge absorbing water. Similarly, mushroom hyphae absorb oxygen from their surroundings, enabling cellular respiration. This process is crucial for energy production, as mushrooms break down organic matter to fuel their growth. Unlike plants, which rely on stomata for gas exchange, mushrooms’ entire surface area acts as an interface for respiration. This adaptability highlights their evolutionary success in nutrient-rich but oxygen-variable habitats.

To observe this in action, place a mushroom in a sealed container with a moist substrate. Over time, you’ll notice subtle changes in its growth and color, indicating active gas exchange. For optimal mushroom cultivation, maintain humidity levels between 85–95% and ensure adequate airflow to prevent CO2 buildup, which can stunt growth. This simple experiment underscores the importance of environmental conditions in supporting fungal respiration.

Comparatively, while humans rely on complex respiratory systems, mushrooms exemplify nature’s simplicity. Their decentralized structure eliminates the need for specialized organs, making them resilient in resource-limited settings. This efficiency has inspired biomimicry in engineering, such as designing breathable materials for sustainable architecture. By studying mushroom respiration, we gain insights into both biological ingenuity and practical applications.

In essence, mushrooms “breathe” through their entire body, a testament to their evolutionary elegance. Understanding this mechanism not only deepens our appreciation for fungi but also offers lessons in efficiency and adaptability. Whether you’re a cultivator, scientist, or enthusiast, recognizing how mushrooms exchange gases unlocks a new perspective on these often-overlooked organisms.

Magic Mushrooms and Brain Health: Separating Fact from Fiction

You may want to see also

Role of mycelium in respiration

Mushrooms, unlike animals, do not have lungs or gills for respiration, yet they still require oxygen to survive. This process is facilitated by their intricate network of mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Mycelium plays a pivotal role in fungal respiration by maximizing surface area for gas exchange, enabling mushrooms to absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide efficiently. This network acts as the fungus’s respiratory system, ensuring metabolic processes continue uninterrupted.

To understand the role of mycelium in respiration, consider its structure. Hyphae, the individual filaments of mycelium, are incredibly thin and densely packed, often spreading over large areas in soil or substrate. This design allows for passive diffusion of gases, where oxygen moves from areas of high concentration (like the surrounding environment) to areas of low concentration (within the fungus). For example, in a forest floor, mycelium can extend for acres, creating a vast interface for gas exchange. This efficiency is why fungi can thrive in environments with limited oxygen availability, such as deep within wood or soil.

Practical applications of mycelium’s respiratory function are emerging in biotechnology. Researchers are exploring how mycelium can be used in biofiltration systems to absorb pollutants, as its high surface area and metabolic activity make it an effective medium for breaking down harmful gases. For instance, mycelium-based filters have been tested to remove volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from indoor air, with studies showing up to 80% reduction in pollutants over 24 hours. To implement this at home, grow oyster mushroom mycelium on coffee grounds or straw in a well-ventilated container, placing it near sources of VOCs like printers or paint.

Comparatively, mycelium’s respiratory efficiency outshines many other biological systems. While plant roots rely on soil pores for oxygen, mycelium actively seeks out oxygen by growing toward it, a process known as positive aerotropism. This adaptability makes fungi resilient in oxygen-depleted environments, such as waterlogged soils, where plants would typically suffocate. For gardeners, incorporating mycelium-rich compost into soil can improve oxygen availability for plant roots, enhancing overall soil health and plant growth.

In conclusion, mycelium is not just the foundation of fungal life but also the key to its respiratory success. Its unique structure and function enable mushrooms to breathe without specialized organs, showcasing nature’s ingenuity. Whether in natural ecosystems or human-designed applications, understanding and harnessing mycelium’s respiratory role opens doors to sustainable solutions in pollution control, agriculture, and beyond.

Mushroom Stems and Drug Testing: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Do mushrooms produce carbon dioxide?

Mushrooms, unlike animals, do not have lungs or a respiratory system, yet they still engage in a form of "breathing" essential for their survival. This process, known as cellular respiration, is how mushrooms convert nutrients into energy, releasing carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a byproduct. While plants primarily release oxygen during photosynthesis, mushrooms, being fungi, rely on decomposing organic matter and follow a metabolic pathway similar to animals. This fundamental biological process raises the question: how significant is the CO₂ production of mushrooms, and what does it mean for their role in ecosystems?

To understand the scale of CO₂ production by mushrooms, consider their metabolic rate. Fungi, including mushrooms, are heterotrophs, meaning they obtain energy by breaking down organic compounds. During this process, glucose is oxidized, releasing CO₂ and water. Studies show that a single mushroom can produce approximately 0.001 to 0.01 grams of CO₂ per day, depending on its size and species. While this may seem negligible compared to human respiration (which produces about 1 kg of CO₂ daily), the cumulative effect of vast fungal networks in forests can be substantial. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, contribute significantly to soil CO₂ levels, influencing carbon cycling in ecosystems.

From a practical standpoint, understanding mushroom CO₂ production has implications for indoor cultivation. Growers must manage ventilation to prevent CO₂ buildup, which can hinder mushroom growth. A well-ventilated growing area with air exchange rates of 1-2 times per hour is recommended. Additionally, monitoring CO₂ levels using portable sensors (aiming for concentrations below 1,000 ppm) can optimize conditions for fruiting bodies. For home growers, this means ensuring grow tents or rooms have adequate airflow, possibly incorporating fans or passive vents.

Comparatively, mushrooms’ CO₂ production pales in contrast to their ecological benefits. Fungi are primary decomposers, breaking down dead organic matter and recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. This process, while releasing CO₂, is crucial for soil health and carbon sequestration. For example, mycelial networks can store up to 36% of the world’s soil carbon, mitigating greenhouse gas effects. Thus, while mushrooms do produce CO₂, their net contribution to ecosystems is overwhelmingly positive, highlighting their role as both breathers and healers of the natural world.

In conclusion, mushrooms do produce carbon dioxide as part of their metabolic processes, but the amount is minimal compared to their ecological importance. Whether in a forest or a grow room, their CO₂ output is a natural consequence of their life cycle, one that supports rather than detracts from environmental balance. By understanding this process, we can better appreciate mushrooms’ dual role as both producers of CO₂ and vital contributors to carbon cycling and ecosystem health.

Solo Mushroom Trips: Safety, Benefits, and What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Impact of oxygen on mushroom growth

Mushrooms, unlike animals, do not have lungs or a respiratory system, yet oxygen plays a pivotal role in their growth and development. Oxygen is essential for the breakdown of glucose in mushroom mycelium, a process known as cellular respiration. This metabolic pathway releases energy, which the fungus uses to grow, produce fruiting bodies, and maintain its structure. Without adequate oxygen, mushrooms cannot efficiently convert nutrients into the energy required for optimal development. This fundamental biological process underscores why oxygen levels in the growing environment are critical for cultivators to monitor and control.

To maximize mushroom growth, maintaining proper oxygen levels is both an art and a science. For instance, in commercial mushroom farming, carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels are often managed by increasing ventilation, which indirectly ensures a steady supply of oxygen. Ideal CO₂ levels for mushroom growth typically range between 800 to 1,500 parts per million (ppm), with oxygen levels remaining close to atmospheric concentrations (21%). However, during the spawning and pinning stages, slightly higher oxygen levels (around 22-23%) can stimulate mycelial activity and fruiting body formation. Practical tips include using fans to circulate air and avoiding over-packing substrate bags, which can restrict airflow and reduce oxygen availability.

A comparative analysis of oxygen’s impact reveals its dual role as both a promoter and inhibitor of mushroom growth. While sufficient oxygen fosters healthy mycelium and robust fruiting bodies, excessive levels can lead to drying of the substrate, hindering growth. Conversely, low oxygen conditions encourage anaerobic respiration, which produces ethanol and other byproducts toxic to the fungus. For example, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are particularly sensitive to oxygen deprivation, with growth rates declining significantly below 17% oxygen concentration. In contrast, some species, like shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*), are more tolerant of lower oxygen levels but still require a minimum of 18% for optimal development.

Persuasively, the precise control of oxygen levels can be a game-changer for mushroom cultivators. Investing in environmental monitoring tools, such as oxygen and CO₂ sensors, allows growers to fine-tune conditions for specific mushroom species. For hobbyists, simple strategies like using perforated grow bags or drilling small holes in containers can improve airflow. Commercial growers might consider automated ventilation systems to maintain consistent oxygen levels across large cultivation areas. By prioritizing oxygen management, cultivators can enhance yield, improve mushroom quality, and reduce the risk of contamination, ultimately leading to more successful harvests.

Can Dogs Eat Mushrooms? Safety Tips for Pet Owners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, mushrooms do not breathe in the same way humans do. They lack lungs and a respiratory system, but they exchange gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide) directly through their cell membranes.

Mushrooms absorb oxygen directly from the air or surrounding environment through diffusion, a process that occurs across their surfaces without the need for specialized organs.

Yes, mushrooms produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct of their metabolic processes, similar to how humans exhale CO2 after respiration.

No, mushrooms require oxygen for cellular respiration, the process by which they break down nutrients to produce energy. Without oxygen, they cannot survive.