While mushrooms are often celebrated for their nutritional benefits and potential therapeutic properties, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that mushrooms can cause bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is a complex mental health condition influenced by genetic, environmental, and neurochemical factors, and it is not linked to the consumption of mushrooms. However, some psychoactive mushrooms, like those containing psilocybin, can induce altered states of consciousness and mood changes, which might temporarily mimic symptoms of bipolar disorder in susceptible individuals. It is crucial to approach such substances with caution and consult healthcare professionals, especially for those with a history of mental health issues.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Direct Causation | No scientific evidence directly links mushroom consumption to causing bipolar disorder. |

| Psilocybin Mushrooms | Some studies suggest psilocybin (found in certain mushrooms) may temporarily induce mood changes or psychotic symptoms in susceptible individuals, but it does not cause bipolar disorder. |

| Mental Health Risks | Psilocybin use in individuals with a predisposition to mental health disorders (e.g., bipolar, schizophrenia) may trigger or exacerbate symptoms, but it does not cause the disorder itself. |

| Therapeutic Potential | Psilocybin is being researched for its potential in treating depression and anxiety, but its effects on bipolar disorder are not well-studied and may be risky. |

| Individual Variability | Responses to mushrooms vary widely; some may experience mood swings or mania-like symptoms, but these are not indicative of bipolar disorder development. |

| Medical Consensus | Bipolar disorder is primarily caused by genetic, environmental, and neurochemical factors, not by mushroom consumption. |

| Recreational Use Risks | Misuse of mushrooms can lead to temporary psychological distress but is not a recognized cause of bipolar disorder. |

| Research Gaps | Limited research specifically explores the link between mushrooms and bipolar disorder, but current evidence does not support causation. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom Types and Bipolar Risk: Identifying specific mushrooms linked to bipolar symptoms or mood changes

- Psilocybin and Mental Health: Exploring psilocybin's effects on bipolar disorder, including potential risks or benefits

- Toxic Mushrooms and Mood Swings: Investigating toxic mushrooms that may trigger bipolar-like symptoms or episodes

- Immune Response and Bipolar: Examining how mushroom consumption might affect immunity, indirectly impacting bipolar disorder

- Anecdotal Evidence vs. Science: Analyzing personal reports of mushrooms causing bipolar symptoms versus scientific research findings

Mushroom Types and Bipolar Risk: Identifying specific mushrooms linked to bipolar symptoms or mood changes

Certain mushrooms, particularly those containing psychoactive compounds, have been anecdotally linked to mood changes and, in rare cases, bipolar-like symptoms. Psilocybin mushrooms, for example, are known to induce altered states of consciousness, euphoria, and introspection. While these effects are often temporary, individuals with a predisposition to mental health disorders may experience prolonged or intensified mood swings. A 2019 study published in *Nature Medicine* found that psilocybin could exacerbate underlying psychiatric conditions in vulnerable populations, though it did not establish a direct causal link to bipolar disorder. Dosage plays a critical role here: microdosing (0.1–0.3 grams) is less likely to trigger severe reactions compared to full doses (1–5 grams), but individual sensitivity varies widely.

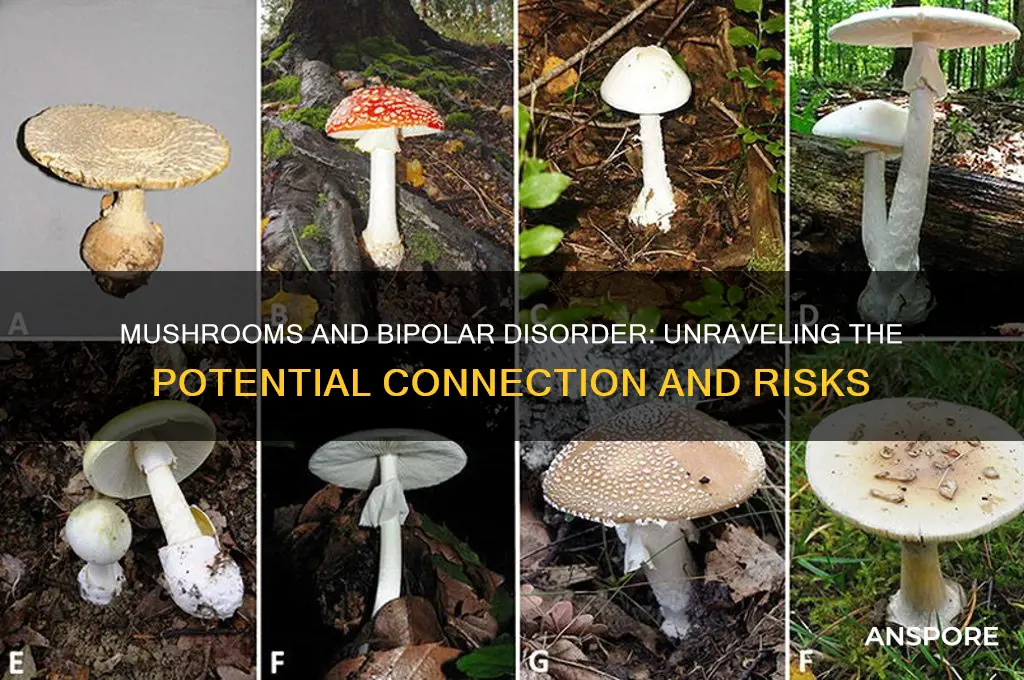

Not all mushrooms pose the same risks. Edible varieties like shiitake, oyster, and button mushrooms are generally safe and lack psychoactive properties. However, Amanita muscaria and Amanita pantherina, often referred to as "fly agaric," contain muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause confusion, agitation, and mood disturbances. These symptoms, while not identical to bipolar disorder, may mimic its manic or hypomanic phases. It’s crucial to avoid misidentification, as these mushrooms are sometimes mistaken for edible species, leading to accidental ingestion and adverse effects. Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide when foraging.

For those with bipolar disorder or a family history of the condition, caution is warranted. Psilocybin therapy, currently under clinical investigation for depression and PTSD, excludes individuals with bipolar disorder due to concerns about triggering manic episodes. A 2021 review in *Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology* highlighted that even controlled therapeutic settings cannot eliminate the risk of mood destabilization in this population. If you’re considering mushroom use, disclose your medical history to a healthcare provider, especially if you’re taking mood stabilizers, as interactions are poorly understood.

Practical tips for minimizing risk include starting with the smallest possible dose and avoiding mushrooms altogether if you have a history of mood disorders. Keep a journal to track any changes in mood or behavior after consumption. For parents and caregivers, educate children about the dangers of wild mushrooms, as accidental ingestion is more common in younger age groups. Finally, prioritize mental health monitoring: if you notice persistent mood swings, irritability, or euphoria after mushroom use, seek professional evaluation immediately. While mushrooms may not directly cause bipolar disorder, their interaction with vulnerable brains can be unpredictable and potentially harmful.

Can Dogs Eat Mushrooms? Safety Tips for Pet Owners

You may want to see also

Psilocybin and Mental Health: Exploring psilocybin's effects on bipolar disorder, including potential risks or benefits

Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in certain mushrooms, has garnered significant attention for its potential therapeutic effects on mental health conditions, including depression and anxiety. However, its impact on bipolar disorder remains a complex and under-researched area. Bipolar disorder, characterized by extreme mood swings, requires careful consideration when exploring novel treatments like psilocybin. While some studies suggest psilocybin’s ability to reset neural pathways could offer benefits, there are concerns about its potential to trigger manic or hypomanic episodes in susceptible individuals.

One critical aspect to consider is the dosage and administration of psilocybin in clinical settings. Research typically involves controlled doses (10–25 mg) administered in a therapeutic environment with psychological support. This structured approach aims to minimize risks while maximizing potential benefits. For individuals with bipolar disorder, even small deviations from this protocol could lead to unpredictable outcomes. For instance, a study published in *Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology* highlighted the importance of screening for bipolar disorder before administering psilocybin, as individuals with a history of mania may be at higher risk of adverse reactions.

Comparatively, the mechanism of psilocybin—which acts on serotonin receptors to promote neuroplasticity—aligns with its potential to alleviate depressive symptoms. However, this same mechanism could theoretically destabilize mood regulation in bipolar patients, particularly during depressive phases. Anecdotal reports and case studies have documented instances where psilocybin use led to prolonged manic episodes or rapid cycling between moods. This duality underscores the need for rigorous clinical trials specifically targeting bipolar populations to establish safety and efficacy.

From a practical standpoint, individuals with bipolar disorder considering psilocybin should prioritize consultation with a psychiatrist or mental health professional. Monitoring for early signs of mood destabilization, such as increased energy, decreased need for sleep, or irritability, is crucial. Additionally, maintaining a stable medication regimen and avoiding self-administration of psilocybin outside clinical trials is strongly advised. While the allure of a breakthrough treatment is compelling, the risks of exacerbating bipolar symptoms cannot be overlooked.

In conclusion, the exploration of psilocybin’s effects on bipolar disorder is a delicate balance between potential therapeutic breakthroughs and significant risks. Current evidence is insufficient to recommend its use in this population, but ongoing research may provide clearer guidelines in the future. For now, caution and professional oversight remain paramount in navigating this emerging frontier of mental health treatment.

Prepping Mushroom Duxelles: Make-Ahead Tips for Perfect Flavor Every Time

You may want to see also

Toxic Mushrooms and Mood Swings: Investigating toxic mushrooms that may trigger bipolar-like symptoms or episodes

Certain mushrooms, particularly those containing psychoactive compounds like psilocybin or toxic substances such as amatoxins, have been linked to mood disturbances that mimic bipolar-like symptoms. While psilocybin mushrooms are more commonly associated with temporary altered states of consciousness, toxic varieties like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) or the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) can induce severe neurological and psychological effects, including confusion, agitation, and rapid mood swings. These symptoms often arise from organ failure or direct neurotoxicity, rather than a primary psychiatric mechanism. Understanding the distinction between psychoactive and toxic mushrooms is crucial, as misidentification can lead to life-threatening consequences.

For instance, accidental ingestion of toxic mushrooms can result in symptoms such as euphoria, paranoia, or depression within 6–24 hours, depending on the species and dosage. Amatoxin-containing mushrooms, for example, cause initial gastrointestinal distress followed by a latent phase where apparent recovery may occur, only to be followed by severe liver and kidney damage. During this phase, patients may exhibit erratic behavior, including manic-like episodes or profound lethargy, which can be mistaken for bipolar disorder. It’s essential to seek immediate medical attention if such symptoms occur, as delayed treatment significantly increases mortality rates.

From a preventive standpoint, proper mushroom identification is paramount. Foraging without expertise is risky, as toxic species often resemble edible varieties. For example, the Death Cap closely resembles the Paddy Straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*), a popular edible species in Asia. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable guides, and consider consulting a mycologist. If experimenting with psychoactive mushrooms, such as those containing psilocybin, ensure a controlled environment and a trusted source to minimize risks of contamination or misidentification. Dosage matters—even small amounts of toxic mushrooms can be fatal, while psychoactive varieties require precise measurement to avoid overwhelming experiences.

Comparatively, while psychoactive mushrooms have been explored for their potential therapeutic effects in mental health, including bipolar disorder, toxic mushrooms offer no such benefits. Studies on psilocybin have shown promise in treating depression and anxiety, but these are administered in controlled, clinical settings. Toxic mushrooms, on the other hand, pose only risks. For those with pre-existing mental health conditions, exposure to toxic mushrooms could exacerbate symptoms or trigger episodes, making avoidance critical. Education and awareness are key to distinguishing between these two categories and their vastly different impacts on mental health.

In conclusion, while mushrooms can indeed induce mood swings or bipolar-like symptoms, the cause lies primarily in toxicity rather than psychoactive properties. Accidental ingestion of toxic species poses a far greater danger than controlled use of psychoactive varieties. Practical steps such as proper identification, avoiding foraging without expertise, and seeking immediate medical attention for suspected poisoning are essential. By understanding these distinctions, individuals can mitigate risks and make informed decisions regarding mushroom consumption or exposure.

Can Mushrooms Detoxify Estrogen? Exploring Their Hormonal Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Immune Response and Bipolar: Examining how mushroom consumption might affect immunity, indirectly impacting bipolar disorder

The relationship between mushroom consumption and bipolar disorder is not straightforward, but emerging research suggests a potential link through immune system modulation. Mushrooms, particularly varieties like lion’s mane, reishi, and cordyceps, contain bioactive compounds such as beta-glucans and polysaccharides that can influence immune responses. For individuals with bipolar disorder, whose condition may be exacerbated by systemic inflammation or immune dysregulation, understanding this interaction is crucial. While mushrooms are generally touted for their immunomodulatory benefits, their effects can vary depending on the type, dosage, and individual health status. For instance, beta-glucans in shiitake mushrooms (at doses of 2–6 grams daily) have been shown to enhance immune function, but overstimulation in sensitive individuals could theoretically trigger inflammatory pathways linked to mood instability.

To examine this further, consider the bidirectional relationship between the immune system and the brain, often referred to as the neuroimmune axis. Chronic inflammation, a common feature in bipolar disorder, can disrupt neurotransmitter balance and neuronal function, potentially worsening symptoms. Mushrooms with anti-inflammatory properties, such as turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), might mitigate this by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-alpha. However, immunostimulatory mushrooms like maitake could have the opposite effect if consumed in excess. For adults, a daily dose of 1–3 grams of mushroom extract is often recommended for immune support, but those with bipolar disorder should monitor their response closely, as even beneficial immune modulation can inadvertently affect mood regulation.

A comparative analysis of mushroom types reveals distinct immunological effects. Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum), for example, acts as an immune regulator, balancing both underactive and overactive immune responses, making it a safer option for those with bipolar disorder. In contrast, lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), while neuroprotective and potentially beneficial for cognitive function, may stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF), which could theoretically interact with mood pathways in unpredictable ways. Practical tips include starting with low doses (e.g., 500 mg of reishi extract daily) and gradually increasing while tracking mood changes. Consultation with a healthcare provider is essential, especially for those on mood stabilizers, as mushrooms can interact with medications like lithium.

From a persuasive standpoint, integrating mushrooms into a bipolar management plan requires caution but holds promise. For instance, a 2020 study in *Nutritional Neuroscience* suggested that dietary interventions targeting inflammation, including mushroom consumption, could adjunctively support bipolar treatment. However, anecdotal reports of mood fluctuations after mushroom use highlight the need for individualized approaches. Middle-aged adults (40–60 years) with bipolar disorder might benefit from incorporating small amounts of anti-inflammatory mushrooms into their diet, paired with consistent monitoring of symptoms. Avoiding raw mushrooms and opting for cooked or extracted forms can also reduce potential gastrointestinal side effects, which could indirectly impact mood.

In conclusion, while mushrooms are not a direct cause of bipolar disorder, their immunomodulatory effects could indirectly influence its course. A tailored, evidence-based approach—considering mushroom type, dosage, and individual health status—is key. For example, a 30-year-old with bipolar II disorder might safely incorporate 1 gram of reishi extract daily, while a 50-year-old with a history of manic episodes should avoid immunostimulatory varieties altogether. By bridging the gap between immune health and mental health, this perspective offers a nuanced understanding of how mushroom consumption might fit into a holistic bipolar management strategy.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Your Basement? A Complete Growing Guide

You may want to see also

Anecdotal Evidence vs. Science: Analyzing personal reports of mushrooms causing bipolar symptoms versus scientific research findings

Personal accounts of mushrooms triggering bipolar symptoms often circulate in online forums and social media, fueling concerns and misconceptions. These anecdotes typically describe individuals who, after consuming mushrooms—whether for culinary, medicinal, or psychoactive purposes—report sudden mood swings, manic episodes, or depressive states resembling bipolar disorder. For instance, a 28-year-old user on a health forum recounted experiencing heightened energy and irritability for weeks following a single dose of psilocybin mushrooms, leading them to question a potential link to bipolar disorder. Such stories are compelling, tapping into the human tendency to seek patterns and causation, but they lack the rigor of scientific scrutiny. Without controlled variables, these reports often conflate correlation with causation, overlooking factors like pre-existing mental health conditions, substance interactions, or placebo effects.

Scientific research, however, paints a more nuanced picture. Studies investigating the relationship between mushrooms and bipolar disorder have yet to establish a direct causal link. Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound in "magic mushrooms," has been studied extensively for its potential therapeutic effects on depression, anxiety, and PTSD, often under controlled, clinical conditions. For example, a 2021 study published in *JAMA Psychiatry* found that psilocybin-assisted therapy significantly reduced depression symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder, with no reported induction of bipolar symptoms. Similarly, research on dietary mushrooms (e.g., shiitake, portobello) has focused on their nutritional benefits, with no evidence linking them to bipolar disorder. While rare cases of psychotic episodes following psilocybin use have been documented, these typically occur in individuals with a predisposition to psychosis or in unsupervised, high-dose settings (e.g., >3 grams of dried mushrooms).

The discrepancy between anecdotal evidence and scientific findings highlights the importance of context and methodology. Anecdotes, while emotionally resonant, often lack critical details such as dosage, frequency of use, and the individual’s mental health history. For instance, a person reporting bipolar-like symptoms after mushroom use might have an undiagnosed predisposition to the disorder, which was merely exacerbated, not caused, by the substance. In contrast, scientific studies employ randomized controlled trials, placebo groups, and longitudinal tracking to isolate variables and establish causality. This methodological rigor ensures that findings are replicable and generalizable, offering a more reliable basis for understanding risks and benefits.

To navigate this complex landscape, individuals should approach both anecdotes and scientific studies with a critical eye. If considering mushroom use—whether for recreational or therapeutic purposes—consult a healthcare professional, especially if there is a personal or family history of mental health disorders. Start with low doses (e.g., 1–2 grams of psilocybin mushrooms) in a controlled environment, and avoid mixing with other substances. For dietary mushrooms, incorporate them as part of a balanced diet, mindful of potential allergies or sensitivities. Ultimately, while anecdotes can spark important conversations, they should not replace evidence-based guidance when it comes to mental health.

Sun-Drying Mushrooms: A Simple Guide to Preserving Your Harvest

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no scientific evidence to suggest that mushrooms directly cause bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is a complex mental health condition influenced by genetic, environmental, and neurological factors, not by mushroom consumption.

Psychedelic mushrooms (containing psilocybin) can trigger psychotic episodes or mood disturbances in individuals predisposed to mental health conditions, but they do not cause bipolar disorder. Use with caution, especially if there is a family history of mental illness.

Edible mushrooms are generally safe and not known to worsen bipolar symptoms. However, individual reactions vary, and it’s best to consult a healthcare provider if you have concerns about dietary triggers.

No direct connection has been established between mushroom use and the development of bipolar disorder. However, substance use, including psychedelics, can exacerbate underlying mental health issues in susceptible individuals.