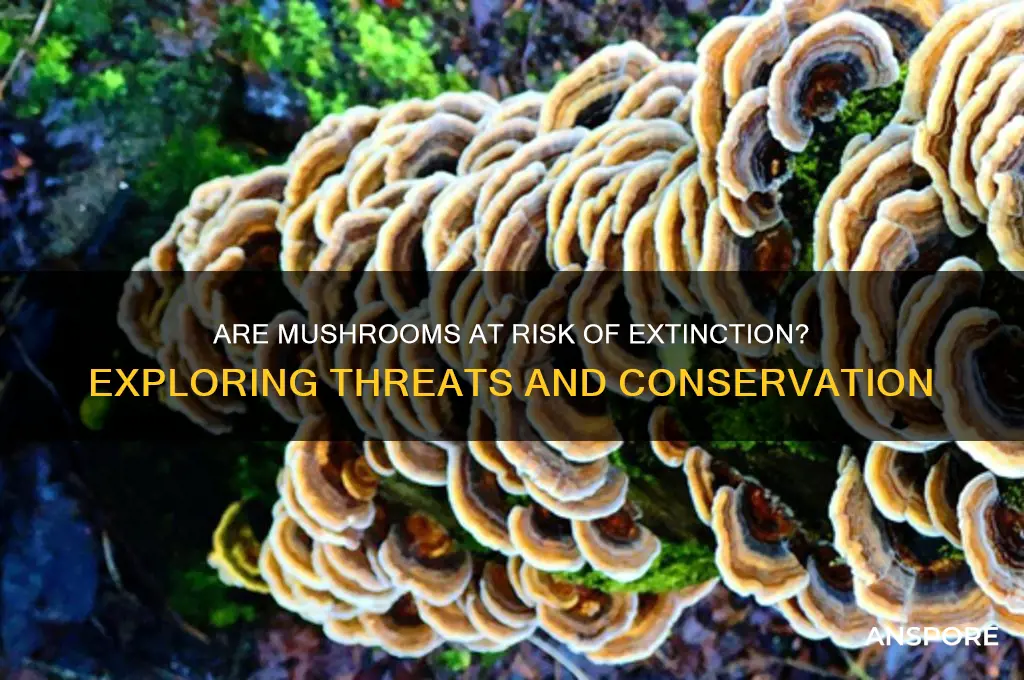

Mushrooms, often overlooked in discussions about biodiversity, play a crucial role in ecosystems worldwide, yet their survival is increasingly threatened by human activities and environmental changes. As key decomposers, they recycle nutrients, support plant growth, and maintain soil health, but factors such as habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and overharvesting are pushing many species to the brink. Unlike animals and plants, mushrooms lack widespread conservation efforts, and their complex life cycles make them particularly vulnerable to extinction. Understanding the risks they face is essential, as the loss of mushroom species could disrupt ecosystems, reduce biodiversity, and have far-reaching consequences for both wildlife and humans.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can mushrooms go extinct? | Yes, mushrooms can go extinct. |

| Threats to mushroom populations | Habitat loss, deforestation, pollution, climate change, over-harvesting, invasive species, disease |

| Vulnerability to extinction | Varies by species; some mushrooms are more resilient than others. Many mushroom species have not been thoroughly studied, making it difficult to assess their conservation status. |

| Conservation status | According to the IUCN Red List, several mushroom species are listed as endangered, vulnerable, or critically endangered. Examples include the Ghost Orchid Mushroom (Didymium difforme) and the Woolly Milkcap (Lactarius torminosus). |

| Role in ecosystems | Mushrooms play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and mutualistic relationships with plants. Their extinction could have cascading effects on entire ecosystems. |

| Current research and conservation efforts | Ongoing research focuses on understanding mushroom biodiversity, ecology, and conservation needs. Some initiatives include habitat restoration, protected areas, and sustainable harvesting practices. |

| Examples of extinct or endangered mushrooms | |

| - Extinct: None confirmed, but many species are likely extinct due to habitat loss and other threats. | |

| - Endangered: Ghost Orchid Mushroom, Woolly Milkcap, and various truffle species. | |

| Human impact on mushroom populations | Significant; human activities such as deforestation, pollution, and over-harvesting directly contribute to mushroom decline. |

| Climate change impact | Altered temperature and precipitation patterns can disrupt mushroom growth, distribution, and symbiotic relationships. |

| Importance of mushroom conservation | Essential for maintaining ecosystem health, biodiversity, and potential medicinal and ecological benefits. |

| Latest data (as of 2023) | Approximately 140,000 mushroom species have been described, but estimates suggest over 2.5 million species exist. Many remain undiscovered or unstudied, highlighting the need for continued research and conservation efforts. |

Explore related products

$23.49 $39.95

What You'll Learn

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation and land conversion threaten mushroom ecosystems, reducing their natural habitats

- Climate Change: Shifting temperatures and rainfall patterns disrupt mushroom growth cycles and distribution

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants and soil contamination can harm mycorrhizal networks essential for mushroom survival

- Overharvesting: Excessive foraging of wild mushrooms depletes populations faster than they can regenerate

- Invasive Species: Non-native fungi and organisms outcompete native mushrooms, reducing biodiversity and survival chances

Habitat Loss: Deforestation and land conversion threaten mushroom ecosystems, reducing their natural habitats

Mushrooms, often overlooked in conservation efforts, are silently suffering from the relentless march of deforestation and land conversion. These fungi, integral to forest ecosystems, rely on specific conditions—moisture, decaying wood, and symbiotic relationships with trees—that are rapidly disappearing. For instance, the iconic Amanita muscaria, a symbol of fairy tales and forest floors, is losing its habitat as old-growth forests are cleared for agriculture and urban development. This isn’t just about losing a species; it’s about disrupting the intricate web of life that mushrooms help sustain, from nutrient cycling to soil health.

Consider the steps involved in land conversion: forests are cleared, soil is tilled, and monoculture crops or concrete structures replace diverse ecosystems. Mushrooms, particularly mycorrhizal species that depend on tree roots, cannot survive in such altered environments. A study in the Amazon found that deforestation reduced fungal diversity by up to 50% in just a decade. Practical tips for mitigating this? Support reforestation projects that prioritize native tree species, as these provide the organic matter and root systems mushrooms need. Even small-scale efforts, like planting oak or beech trees in urban green spaces, can create microhabitats for fungi to thrive.

The persuasive argument here is clear: habitat loss isn’t just a threat to charismatic megafauna; it’s a death sentence for the unseen architects of ecosystems. Take the example of truffle-producing fungi, which require specific soil conditions and undisturbed habitats. In Europe, truffle yields have declined by 30% in the past 50 years due to land conversion and climate change. This isn’t just a culinary loss—truffles play a role in soil aeration and nutrient distribution. To protect these fungi, advocate for land-use policies that preserve natural habitats and limit fragmentation. A caution: while agroforestry can help, it’s not a silver bullet; mushrooms need diverse, undisturbed ecosystems to flourish.

Comparatively, the plight of mushrooms mirrors that of pollinators, yet they receive a fraction of the attention. Bees and butterflies have campaigns and conservation programs, but mushrooms? Rarely. This oversight is dangerous. Fungi are keystone species in many ecosystems, and their decline could trigger cascading effects, from reduced carbon sequestration to the loss of medicinal compounds. For instance, the fungus *Penicillium* gave us penicillin, and countless undiscovered species may hold cures for diseases like cancer. The takeaway? Protecting mushroom habitats isn’t just about saving fungi—it’s about safeguarding the health of our planet and ourselves. Start by educating others, supporting fungi-focused research, and demanding policies that treat forests as more than timber resources.

Are Mushrooms with Small Spots Safe to Eat? Find Out Here

You may want to see also

Climate Change: Shifting temperatures and rainfall patterns disrupt mushroom growth cycles and distribution

Mushrooms, often overlooked in discussions about climate change, are highly sensitive to environmental shifts. Their growth cycles are intricately tied to specific temperature and moisture conditions, which are now being disrupted by global warming. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with trees, rely on consistent soil temperatures to thrive. Even a 1°C increase can alter their metabolic rates, leading to reduced spore production and weaker root associations. This isn’t just a theoretical concern—studies in the Pacific Northwest have already documented declines in truffle populations, a critical food source for wildlife and humans alike.

Consider the lifecycle of the morel mushroom, a delicacy prized by foragers. Morels typically emerge in spring after forest fires, relying on a precise balance of warmth and moisture. However, prolonged droughts followed by intense rainfall—a hallmark of climate change—can desiccate their mycelium or drown emerging fruiting bodies. For foragers, this unpredictability means fewer harvests and economic losses. To adapt, enthusiasts are now tracking hyperlocal weather patterns and soil conditions, using apps like iNaturalist to document shifts in mushroom distribution. Practical tip: If you’re a forager, invest in a soil moisture meter and monitor regional climate forecasts to anticipate mushroom seasons.

The impact isn’t limited to wild mushrooms; cultivated varieties are equally vulnerable. Shiitake and oyster mushrooms, grown commercially in controlled environments, require stable humidity levels (85-95%) and temperatures (15-25°C). Climate-induced heatwaves can disrupt these conditions, leading to mold outbreaks or stunted growth. Farmers are responding by installing expensive cooling systems or relocating to cooler regions, but these solutions are unsustainable for small-scale producers. Comparative analysis shows that indoor farms in temperate zones are faring better than those in tropical regions, where humidity fluctuations are more extreme. Takeaway: Diversifying mushroom species in cultivation—such as heat-tolerant strains like the lion’s mane—can mitigate risks.

Finally, the broader ecological implications cannot be ignored. Mushrooms play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling, decomposing organic matter and releasing carbon back into the soil. When their growth cycles are disrupted, this process slows, exacerbating carbon buildup in ecosystems. For example, the decline of Amanita muscaria in boreal forests has been linked to reduced soil fertility, affecting tree health and biodiversity. To combat this, conservationists are experimenting with mycorrhizal inoculation—introducing fungi to degraded soils to restore balance. Step-by-step: Collect spores from healthy mushrooms, mix them with a substrate like wood chips, and distribute in affected areas during the rainy season for optimal absorption. Caution: Ensure the fungi are native to the region to avoid ecological disruption. Conclusion: While mushrooms may not face extinction outright, their delicate balance with the environment underscores the urgency of addressing climate change.

How to Inoculate Grain with Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

Pollution: Chemical pollutants and soil contamination can harm mycorrhizal networks essential for mushroom survival

Chemical pollutants, from industrial runoff to agricultural pesticides, infiltrate soils at alarming rates, disrupting the delicate mycorrhizal networks that mushrooms rely on for survival. These networks, often referred to as the "wood wide web," facilitate nutrient exchange between fungi and plant roots, forming the backbone of forest ecosystems. Studies show that even low concentrations of pollutants like heavy metals (e.g., lead, cadmium) and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) can inhibit mycelial growth and reduce spore germination rates by up to 50%. For instance, a 2020 study in *Environmental Science & Technology* found that soils contaminated with glyphosate, a common herbicide, decreased mycorrhizal colonization by 30% in just six weeks.

To mitigate these effects, consider soil remediation techniques such as phytoremediation, where plants like sunflowers or willows are used to absorb and break down contaminants. For gardeners and farmers, reducing chemical inputs and adopting organic practices can protect mycorrhizal networks. Test soil regularly for pollutants using kits available for under $50, and avoid areas near industrial sites or heavily trafficked roads when foraging for mushrooms. Even small actions, like composting organic waste instead of using synthetic fertilizers, can restore soil health and support fungal resilience.

Persuasively, the loss of mycorrhizal networks isn’t just a threat to mushrooms—it’s a threat to global biodiversity. These networks sustain 90% of plant species, and their collapse could trigger cascading ecosystem failures. Compare this to the decline of bees: just as pollinators are vital for crops, mycorrhizal fungi are essential for forest regeneration. Governments and corporations must prioritize stricter regulations on chemical pollutants, particularly in regions with high fungal diversity like the Amazon or Appalachian Mountains. Public awareness campaigns, akin to those for coral reefs, could highlight the unseen role of fungi in ecosystem stability.

Descriptively, imagine a forest floor once teeming with chanterelles and morels, now barren due to soil contamination. The absence of mushrooms signals a deeper crisis: trees weaken, carbon sequestration slows, and wildlife loses critical food sources. In contaminated areas, mycelium struggles to form the intricate webs that once connected roots across acres. This isn’t a distant future—it’s already happening in industrial zones and monoculture farms. Yet, there’s hope in restoration efforts like the reintroduction of native fungi species and the creation of "fungal corridors" to reconnect fragmented habitats.

Practically, individuals can contribute by supporting mycorrhizal-friendly practices. Plant native trees and shrubs, which form stronger symbiotic relationships with local fungi. Avoid tilling soil excessively, as this damages mycelial structures. For urban dwellers, grow mycorrhizal-associated plants in balconies or community gardens, using organic soil amendments like worm castings. Schools and universities can incorporate fungal ecology into curricula, fostering a new generation of stewards. Every action, no matter how small, helps safeguard these invisible lifelines against the silent threat of pollution.

Can Mushrooms Thrive Without Oxygen? Exploring Anaerobic Growth Conditions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$32.5 $32.5

Overharvesting: Excessive foraging of wild mushrooms depletes populations faster than they can regenerate

Wild mushrooms, often foraged for culinary delights or medicinal properties, face a silent threat: overharvesting. Unlike cultivated varieties, many wild species grow slowly and reproduce through delicate mycelial networks. When foragers collect mushrooms in excess, they disrupt these networks, preventing spores from dispersing and new growth from emerging. For instance, the prized *Tricholoma magnivelare* (Puffy White Mushroom) takes years to establish a robust colony, yet a single overzealous harvest can decimate its population in an area. This imbalance accelerates depletion, outpacing the species’ natural regeneration rate.

Consider the lifecycle of mushrooms: they rely on mycelium, a subterranean web, to absorb nutrients and produce fruiting bodies. Overharvesting not only removes these bodies but also weakens the mycelium, reducing its ability to recover. In regions like the Pacific Northwest, where *Morchella* (morel) mushrooms are heavily foraged, studies show that repeated overcollection has led to a 30% decline in local populations over the past decade. Foragers often overlook the long-term consequences, focusing instead on immediate gains, whether for personal use or commercial sale.

To mitigate this, sustainable foraging practices are essential. A practical rule of thumb is the "two-thirds rule": leave at least two-thirds of mushrooms in any patch to ensure spore dispersal and mycelial health. Additionally, avoid harvesting in the same location annually, giving ecosystems time to recover. Foraging guides and apps can help identify less vulnerable species, such as *Coprinus comatus* (Shaggy Mane), which regenerates more quickly than rarer varieties. Educating foragers about these practices is crucial, as awareness alone can significantly reduce overharvesting.

Comparatively, overharvesting mushrooms mirrors the plight of other wild-harvested resources, like ginseng or certain fish species. However, mushrooms’ hidden growth mechanisms make their decline less visible, often going unnoticed until populations are critically low. Unlike plants, which can regrow from seeds, mushrooms depend on intact mycelium for survival. This unique vulnerability underscores the need for stricter regulations and community-driven conservation efforts, such as those implemented in parts of Europe, where permits and quotas limit mushroom collection in protected areas.

In conclusion, overharvesting wild mushrooms is not merely a localized issue but a global concern with ecological repercussions. By adopting mindful foraging habits and supporting conservation initiatives, individuals can help preserve these fungi for future generations. The key lies in balancing human use with the natural rhythms of mushroom ecosystems, ensuring that the thrill of the hunt doesn’t come at the cost of their existence.

Freezing Mushrooms and Rice: A Complete Guide to Preservation

You may want to see also

Invasive Species: Non-native fungi and organisms outcompete native mushrooms, reducing biodiversity and survival chances

Invasive species pose a silent yet devastating threat to native mushroom populations, often outcompeting them for resources and habitat. For instance, the introduction of the non-native *Amillaria* species in North American forests has led to the decline of indigenous mycorrhizal fungi, which are essential for tree health. These invasive fungi colonize root systems more aggressively, disrupting symbiotic relationships and reducing the survival chances of native mushrooms. Such ecological imbalances highlight the fragility of fungal ecosystems and the urgent need for targeted conservation efforts.

To combat this issue, mycologists recommend proactive measures such as strict biosecurity protocols to prevent the accidental introduction of invasive species. For example, cleaning hiking boots and gardening tools before entering new environments can reduce the spread of fungal spores. Additionally, monitoring programs that track invasive fungi in vulnerable areas can provide early warnings, allowing for timely interventions. For gardeners and forest managers, avoiding the use of non-native mushroom species in landscaping or restoration projects is crucial, as these can quickly dominate and displace local varieties.

A comparative analysis reveals that invasive fungi often thrive due to their adaptability and lack of natural predators in new environments. Unlike native mushrooms, which have co-evolved with local organisms, invasive species face fewer checks on their growth, giving them a competitive edge. For instance, the *Ophiostoma novo-ulmi* fungus, responsible for Dutch elm disease, has decimated elm trees and their associated fungal communities across Europe and North America. This example underscores the cascading effects of invasive species on entire ecosystems, not just individual mushroom populations.

Persuasively, it’s clear that preserving native mushroom biodiversity requires a shift in perspective—from viewing fungi as passive organisms to recognizing them as dynamic, interconnected components of ecosystems. Educating the public about the risks of invasive species and promoting sustainable practices can foster a culture of stewardship. For instance, schools and community groups can organize workshops on identifying invasive fungi and restoring native habitats. By taking collective action, we can mitigate the threat posed by invasive species and ensure the long-term survival of native mushrooms.

Freezing Psychedelic Mushrooms: Preservation Tips and Potential Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mushrooms can go extinct due to habitat loss, climate change, pollution, overharvesting, and invasive species.

Factors include deforestation, soil degradation, pollution, climate change, and unsustainable harvesting practices.

While documentation is limited, some mushroom species are believed to have disappeared due to habitat destruction and environmental changes.

Climate change alters temperature and humidity levels, disrupting the symbiotic relationships mushrooms rely on and reducing their habitats.

Conservation efforts such as protecting natural habitats, sustainable foraging, reducing pollution, and supporting mycological research can help preserve mushroom species.