Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants, are actually fungi and belong to a distinct kingdom of organisms. Unlike plants, which have roots to anchor themselves and absorb water and nutrients, mushrooms lack true roots. Instead, they possess a network of thread-like structures called mycelium that grow underground or within their substrate. This mycelium serves as the mushroom's primary means of nutrient absorption and support, though it functions differently from plant roots. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the unique biology of fungi and their role in ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do mushrooms have roots? | No, mushrooms do not have roots. |

| Structure responsible for nutrient absorption | Mycelium, a network of thread-like filaments called hyphae, acts as the absorptive organ. |

| Function of mycelium | Absorbs water, nutrients, and minerals from the substrate (e.g., soil, wood). |

| Anchor for mushrooms | Mycelium also serves as an anchor, securing the mushroom to its substrate. |

| Comparison to plant roots | Unlike plant roots, mycelium lacks specialized tissues for water and nutrient transport. |

| Scientific classification | Mushrooms are fungi, belonging to the kingdom Fungi, whereas plants belong to the kingdom Plantae. |

| Growth habit | Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, produced by the mycelium under specific conditions. |

| Substrate dependence | Mushrooms rely on their substrate for nutrients, but do not form root-like structures. |

| Common misconception | The stem-like structure of a mushroom (stipe) is often mistaken for a root, but it is not absorptive. |

| Ecosystem role | Mycelium plays a crucial role in decomposing organic matter and nutrient cycling in ecosystems. |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Mycelium vs. Roots: Mushrooms lack true roots; mycelium networks absorb nutrients from substrates

- Anchoring Structures: Some fungi use rhizomorphs or root-like structures for stability in soil

- Nutrient Absorption: Mycelium efficiently extracts nutrients, mimicking root functions without being roots

- Ecology of Fungi: Fungi decompose organic matter, playing a role distinct from plant roots

- Comparative Anatomy: Mushrooms have no vascular tissue, differing fundamentally from plant root systems

Mycelium vs. Roots: Mushrooms lack true roots; mycelium networks absorb nutrients from substrates

Mushrooms, unlike plants, do not possess true roots. Instead, they rely on a complex network of thread-like structures called mycelium to absorb nutrients from their environment. This fundamental difference in nutrient acquisition highlights the unique biology of fungi, setting them apart from the plant kingdom. While roots are specialized organs that anchor plants and draw water and minerals from the soil, mycelium serves a dual purpose: it both anchors the mushroom and acts as its digestive system, breaking down organic matter in substrates like wood, soil, or decaying leaves.

To understand the efficiency of mycelium, consider its structure. Mycelium consists of tiny filaments called hyphae, which can spread over vast areas, sometimes covering acres underground. This expansive network allows mushrooms to access nutrients that are unavailable to plants with localized root systems. For instance, mycelium can penetrate tiny crevices in wood, secreting enzymes to decompose cellulose and lignin, compounds indigestible to most organisms. This process not only sustains the mushroom but also plays a critical role in ecosystem nutrient cycling, breaking down complex organic materials into simpler forms.

From a practical standpoint, understanding mycelium’s role is essential for cultivating mushrooms. Unlike gardening, where soil quality and root health are paramount, mushroom cultivation focuses on substrate preparation. Growers must provide materials rich in organic matter, such as straw, sawdust, or compost, for mycelium to colonize. Maintaining optimal moisture and temperature levels is crucial, as mycelium thrives in humid, cool environments. For example, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) grow best on straw substrates kept at 60-70°F (15-21°C) with consistent moisture, allowing the mycelium to efficiently break down the material and produce fruiting bodies.

Comparatively, the absence of true roots in mushrooms offers both advantages and challenges. While mycelium’s adaptability allows fungi to thrive in diverse habitats, from forests to deserts, it also makes them vulnerable to environmental changes. Unlike roots, which can store water and nutrients, mycelium relies on a constant supply of organic matter. This dependency underscores the importance of sustainable practices in mushroom cultivation and foraging, ensuring substrates are not depleted. For instance, using agricultural waste as substrate not only supports mushroom growth but also recycles organic materials, reducing environmental impact.

In conclusion, the mycelium network is a marvel of fungal biology, compensating for the absence of true roots with unparalleled efficiency and adaptability. By absorbing nutrients directly from substrates, mycelium sustains mushrooms while contributing to ecosystem health. Whether you’re a cultivator, forager, or simply curious about fungi, understanding this distinction between mycelium and roots provides valuable insights into the unique role mushrooms play in nature and their potential applications in agriculture, ecology, and beyond.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Zero Gravity? Exploring Space Fungus Potential

You may want to see also

Anchoring Structures: Some fungi use rhizomorphs or root-like structures for stability in soil

Fungi, often misunderstood as simple organisms, have evolved intricate strategies to thrive in diverse environments. One such adaptation is the development of rhizomorphs—root-like structures that anchor fungi firmly in soil. Unlike plant roots, which absorb water and nutrients, rhizomorphs primarily provide stability, allowing fungi to withstand environmental stresses like wind, water, or animal disturbance. These structures are particularly common in wood-decaying fungi, such as *Armillaria* species, where they form dense networks that can span meters underground.

To understand rhizomorphs, imagine them as fungal "anchors." Composed of tightly packed hyphae (the thread-like cells of fungi), they are often melanized, meaning they contain dark pigments that enhance durability. This melanin acts as a protective shield, safeguarding the fungus from microbial attack and UV radiation. For gardeners or foresters, recognizing rhizomorphs is crucial: their presence indicates a well-established fungal network, which can either benefit or harm nearby plants, depending on the species.

Practical observation of rhizomorphs requires minimal tools. A trowel and a keen eye suffice. When excavating soil around the base of trees or decaying wood, look for black or brown cord-like structures. These are rhizomorphs, often radiating outward from the fungal source. For those studying fungal ecology, documenting their distribution can reveal how fungi colonize new areas. A simple mapping exercise using stakes and string can track their spread over time, offering insights into fungal behavior.

While rhizomorphs are fascinating, their presence isn’t always benign. In agriculture, certain fungi with rhizomorphs, like *Armillaria*, can cause root rot in crops. To mitigate this, rotate crops annually and avoid planting susceptible species in areas with known fungal activity. For forest managers, monitoring rhizomorph density can predict potential tree mortality, allowing for proactive measures like selective thinning or soil treatment.

In conclusion, rhizomorphs exemplify fungi’s ingenuity in adapting to their environment. By anchoring themselves securely, these organisms ensure survival and expansion, even in challenging conditions. Whether you’re a hobbyist mycologist or a professional, understanding these structures deepens your appreciation of fungal ecology and equips you to manage their impact effectively. Next time you dig into the soil, take a moment to search for these hidden anchors—they tell a story of resilience and resourcefulness.

Can Mushrooms Grow on Clothes? Uncovering the Surprising Truth

You may want to see also

Nutrient Absorption: Mycelium efficiently extracts nutrients, mimicking root functions without being roots

Mushrooms, unlike plants, lack true roots, yet they thrive by employing a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. This mycelium acts as a subterranean nutrient scavenger, efficiently extracting essential elements from its environment. While it doesn’t resemble traditional roots in structure or function, its role in nutrient absorption is strikingly similar, challenging our understanding of how organisms acquire sustenance.

Consider the process: mycelium secretes enzymes that break down complex organic matter—dead leaves, wood, or soil particles—into simpler compounds. These compounds are then absorbed directly through the mycelial network, fueling the mushroom’s growth. This mechanism mirrors root systems in plants, which release acids to solubilize minerals and transport them to the plant body. However, mycelium operates with a finesse that allows it to access nutrients in environments where roots might falter, such as dense wood or nutrient-poor soils.

For gardeners or cultivators, understanding this process can revolutionize how we nurture mushrooms. Instead of focusing on soil fertility alone, creating a substrate rich in organic matter—like straw, sawdust, or compost—encourages mycelial growth. Maintaining a slightly acidic pH (around 5.5–6.5) enhances enzyme activity, optimizing nutrient extraction. For instance, oyster mushrooms thrive in straw-based substrates, while shiitakes prefer hardwood sawdust, demonstrating how substrate selection aligns with mycelial preferences.

A cautionary note: while mycelium is adept at nutrient absorption, it is also sensitive to contaminants. Avoid using substrates treated with pesticides or heavy metals, as mycelium can accumulate these toxins, rendering mushrooms unsafe for consumption. Additionally, proper sterilization of substrates (e.g., steaming at 100°C for 1–2 hours) prevents competing microorganisms from hindering mycelial growth.

In essence, mycelium’s nutrient absorption capabilities highlight its evolutionary ingenuity. By mimicking root functions without being roots, it not only sustains mushrooms but also plays a vital role in ecosystem nutrient cycling. For cultivators, this knowledge translates into practical strategies for optimizing mushroom yields, proving that understanding nature’s subtleties can yield profound results.

Mushrooms in Dog Poop: Unlikely Growth or Common Occurrence?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.39 $19.99

Ecology of Fungi: Fungi decompose organic matter, playing a role distinct from plant roots

Fungi, unlike plants, lack roots in the traditional sense. Instead, they form a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, collectively known as mycelium. This mycelium is the primary organ for nutrient absorption, allowing fungi to decompose organic matter efficiently. While plant roots primarily anchor the plant and absorb water and minerals from the soil, fungal mycelium secretes enzymes to break down complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin, which are indigestible to most other organisms. This process not only recycles nutrients back into the ecosystem but also highlights the unique ecological role of fungi as decomposers.

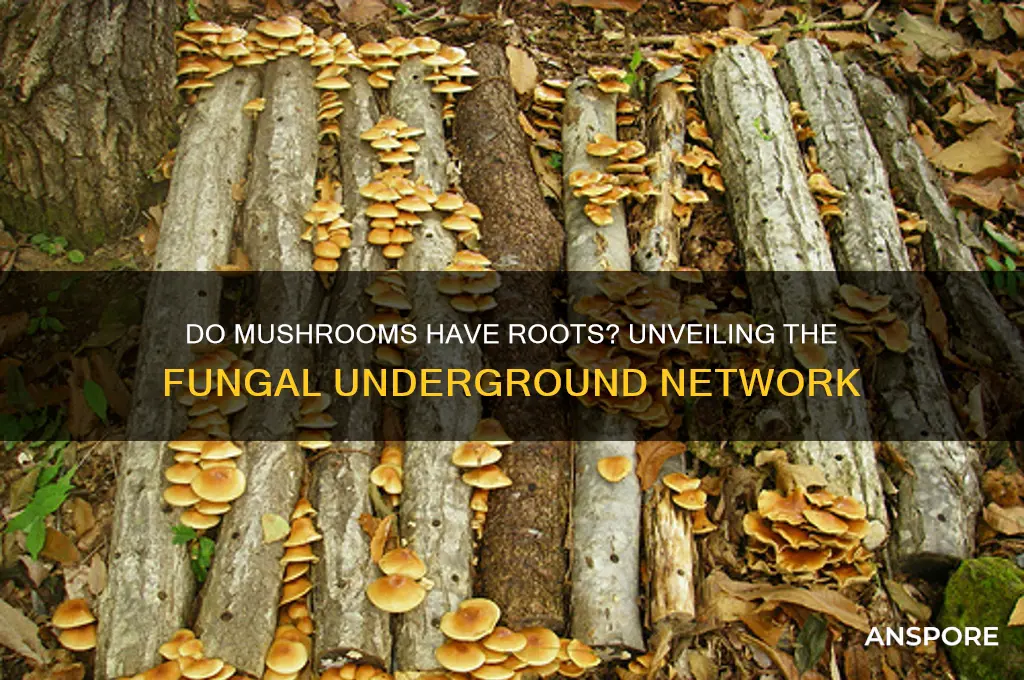

Consider the forest floor, where fallen leaves and dead trees accumulate. Without fungi, this organic matter would remain largely intact, depriving the soil of essential nutrients. Fungi, through their mycelium, penetrate these materials, releasing enzymes that break down tough plant fibers. For instance, certain species of white-rot fungi can degrade lignin, a process that even bacteria struggle to accomplish. This ability makes fungi indispensable in nutrient cycling, ensuring that carbon, nitrogen, and other elements are returned to the soil, where they can be used by plants and other organisms.

To understand the practical implications, imagine a garden where fungal activity is suppressed. Over time, organic debris would pile up, leading to poor soil structure and reduced fertility. Gardeners can encourage fungal growth by adding compost or mulch, which provides a substrate for mycelium to thrive. Additionally, avoiding excessive tilling preserves the delicate network of hyphae, allowing fungi to continue their decomposition work undisturbed. For those interested in fostering fungal ecosystems, introducing mycorrhizal fungi—which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots—can enhance nutrient uptake in plants while supporting fungal decomposition processes.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between fungal and plant root systems. Plant roots are rigid, localized structures that primarily serve to anchor the plant and absorb water and minerals. In contrast, fungal mycelium is flexible, expansive, and focused on breaking down organic matter. This distinction underscores why fungi are often referred to as nature’s recyclers. While plant roots support growth, fungal mycelium facilitates decay, a process equally vital for ecosystem health. Recognizing this difference is crucial for anyone studying or managing ecosystems, as it informs strategies for soil conservation, agriculture, and biodiversity preservation.

In conclusion, the ecology of fungi is defined by their ability to decompose organic matter through their mycelium, a function that sets them apart from plant roots. By breaking down complex materials, fungi play a critical role in nutrient cycling, ensuring the sustainability of ecosystems. Whether in a forest, garden, or agricultural field, understanding and supporting fungal activity can lead to healthier soils and more resilient environments. Practical steps, such as adding organic matter and minimizing soil disturbance, can help harness the power of fungi, making them an ally in both natural and managed landscapes.

Mushroom Cultivation on Half Slabs: Exploring Unique Growing Surfaces

You may want to see also

Comparative Anatomy: Mushrooms have no vascular tissue, differing fundamentally from plant root systems

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants, lack a critical component that defines plant root systems: vascular tissue. This absence fundamentally distinguishes fungi from plants, reshaping how we understand their growth and nutrient absorption. While plant roots rely on xylem and phloem to transport water, nutrients, and sugars, mushrooms use a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. This mycelium operates differently, absorbing nutrients directly from the substrate through osmosis and diffusion, a process far less efficient than the active transport seen in vascular plants.

To illustrate this difference, consider how a tree’s roots draw water from deep soil layers and transport it to leaves via xylem. Mushrooms, in contrast, cannot perform this long-distance transport. Their mycelium remains in direct contact with the nutrient source, often decomposing organic matter to release essential elements. This limitation explains why mushrooms thrive in nutrient-rich environments like forests or compost but struggle in barren soils. For gardeners cultivating mushrooms, ensuring a substrate rich in organic material—such as straw, wood chips, or manure—is crucial, as the mycelium cannot seek nutrients beyond its immediate surroundings.

The absence of vascular tissue also affects mushroom structure and function. Plant roots anchor the organism and store energy, but mushrooms rely on their mycelium for both absorption and structural support. This mycelium forms a dense, interconnected network that can span acres underground, yet it lacks the rigidity of plant roots. For instance, while a carrot’s taproot stores carbohydrates, a mushroom’s fruiting body is ephemeral, existing solely to disperse spores. This distinction highlights why mushrooms cannot be cultivated like root vegetables; their growth depends entirely on the health and spread of their mycelium.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this anatomical difference is key to successful mushroom cultivation. Unlike planting a seed and watering it, growing mushrooms requires inoculating a substrate with mycelium and maintaining optimal humidity and temperature. For example, shiitake mushrooms thrive on hardwood logs, while oyster mushrooms prefer straw. Overwatering can drown the mycelium, as it lacks the vascular system to regulate water uptake. Cultivators must monitor moisture levels carefully, often misting the environment rather than saturating the substrate. This approach mimics the natural conditions where mushrooms flourish, emphasizing the importance of respecting their unique biology.

In summary, the absence of vascular tissue in mushrooms is not a limitation but a defining feature that shapes their ecology and cultivation. By recognizing this fundamental difference from plant root systems, we can better appreciate mushrooms’ role in ecosystems and optimize their growth in controlled environments. Whether foraging in the wild or cultivating at home, this comparative anatomy offers practical insights into why mushrooms are neither plants nor simple organisms but a distinct kingdom with its own rules for survival and propagation.

Can Mushrooms Thrive on Flash Drives? Unlikely Fungal Growth Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms do not have roots like plants. Instead, they have a network of thread-like structures called mycelium that absorb nutrients from their environment.

Mushrooms use mycelium, a web of tiny filaments, to anchor themselves and extract nutrients from organic matter, soil, or decaying material.

Mushrooms can grow in various substrates, such as wood, compost, or soil, but they do not rely on soil in the same way plants do. Their mycelium adapts to the available environment.