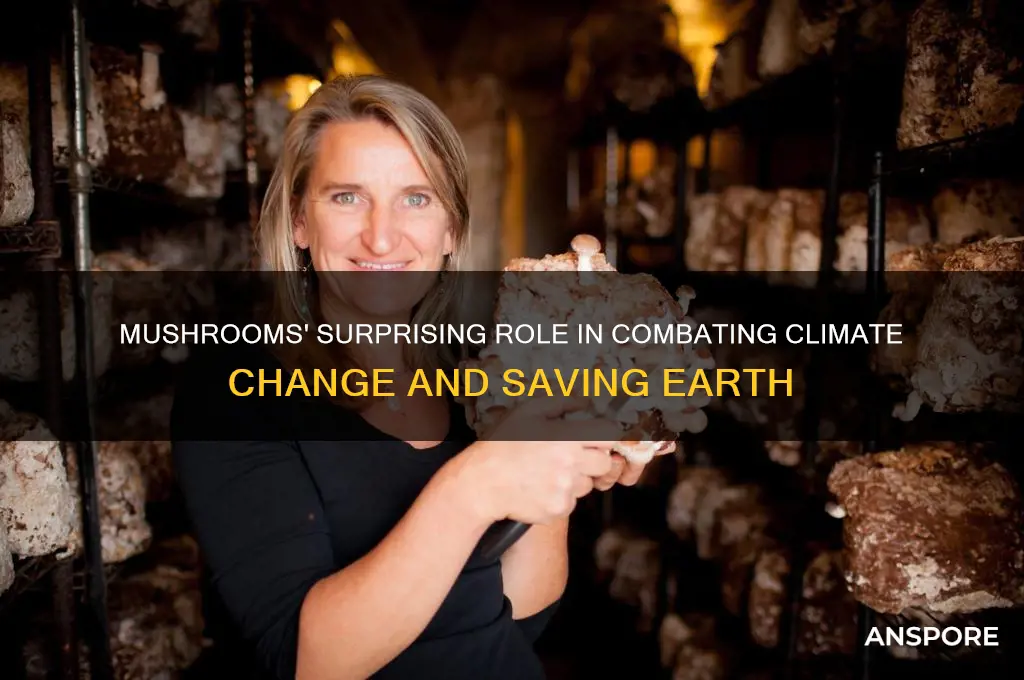

Mushrooms, often overlooked in discussions about environmental solutions, hold remarkable potential to address some of the planet’s most pressing challenges. From their ability to decompose pollutants and restore ecosystems through mycoremediation, to their role in sustainable agriculture as natural pesticides and soil enrichers, fungi are proving to be ecological powerhouses. Beyond their environmental benefits, mushrooms offer a low-carbon, nutrient-dense food source and are being explored as alternatives to plastic, leather, and even building materials. As climate change and resource depletion accelerate, the humble mushroom emerges as a versatile and sustainable ally, sparking hope that these fungi could play a pivotal role in saving the planet.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycoremediation: Mushrooms absorb pollutants, cleaning soil, water, and air effectively

- Sustainable packaging: Mushroom-based materials replace plastic, reducing waste

- Carbon sequestration: Fungi store carbon, combating climate change

- Food security: High-protein mushrooms offer sustainable, scalable nutrition

- Biodegradable leather: Mushroom leather alternatives reduce environmental impact

Mycoremediation: Mushrooms absorb pollutants, cleaning soil, water, and air effectively

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary uses, possess a lesser-known superpower: mycoremediation. This process leverages fungi’s natural ability to absorb and break down pollutants, effectively cleaning soil, water, and air. Unlike chemical treatments, mycoremediation is organic, sustainable, and often more cost-effective. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) have been used to remove petroleum hydrocarbons from contaminated soil, reducing toxicity by up to 95% within weeks. This isn’t science fiction—it’s a proven method already in use across the globe.

To implement mycoremediation, start by identifying the pollutant type and selecting the appropriate mushroom species. For oil spills, oyster mushrooms excel; for heavy metals like lead or mercury, shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) or reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*) are effective. The process involves inoculating contaminated soil or water with mushroom mycelium, which acts as a biofilter. Dosage matters: a 10% mycelium-to-soil ratio is often recommended for optimal results. Monitor pH levels, as mycelium thrives in slightly acidic to neutral conditions (pH 5.5–7.0). Regular testing of pollutant levels will track progress, ensuring the fungi are doing their job.

One of the most compelling aspects of mycoremediation is its versatility. In urban areas, mushrooms can clean air by absorbing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) through their mycelial networks. In rural settings, they restore farmland contaminated by pesticides or industrial runoff. Take the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster: mycologist Paul Stamets proposed using *Trichoderma* fungi to neutralize radiation in soil, though the idea remains untested at scale. While not a silver bullet, mycoremediation offers a complementary solution to traditional cleanup methods, particularly in resource-limited regions.

Critics argue that mycoremediation is slow and unpredictable compared to chemical treatments. However, its long-term benefits outweigh these drawbacks. Fungi not only remove pollutants but also restore soil health by improving structure and nutrient cycling. Plus, the mushrooms themselves can often be harvested and repurposed—edible species for food, others for medicinal extracts or biodegradable packaging. This dual functionality makes mycoremediation a win-win for both environmental cleanup and resource utilization.

In practice, mycoremediation is accessible to individuals and communities alike. Backyard gardeners can use oyster mushrooms to detoxify soil contaminated by lawn chemicals, while municipalities can deploy fungi to clean up industrial sites. DIY kits are available for small-scale projects, though larger operations require expert consultation. The key is patience—mycoremediation is a marathon, not a sprint. Yet, as climate crises escalate, this ancient biological process offers a modern solution, proving that mushrooms aren’t just food or medicine—they’re environmental allies.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Zero Gravity? Exploring Space Fungus Potential

You may want to see also

Sustainable packaging: Mushroom-based materials replace plastic, reducing waste

Plastic waste is a global crisis, with over 300 million tons produced annually, much of which ends up in landfills or oceans. Mushroom-based packaging offers a biodegradable alternative that decomposes in weeks, not centuries. Companies like Ecovative Design have pioneered this technology, using mycelium—the root structure of fungi—to create sturdy, compostable materials. By replacing plastic with mushroom-based solutions, industries can drastically reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining functionality.

To implement mushroom-based packaging, businesses should follow a three-step process. First, assess product needs—mycelium packaging is ideal for protective cushioning, containers, and insulation. Second, partner with suppliers like Ecovative or MycoWorks, who provide customizable solutions. Third, educate consumers on proper disposal, as these materials are home-compostable but require specific conditions to break down efficiently. For instance, packaging should be buried in soil or added to a compost bin, not thrown in regular trash.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantages of mushroom-based materials over traditional plastics. Unlike polystyrene, which takes 500 years to decompose, mycelium packaging breaks down in 45 days, leaving no toxic residue. It’s also lighter, reducing transportation emissions, and requires no harmful chemicals in production. However, scalability remains a challenge, as current production capacities are limited compared to plastic manufacturing. Investing in research and infrastructure could address this gap, making mushroom packaging a viable global solution.

Persuasively, the economic and environmental benefits of adopting mushroom-based packaging are undeniable. Brands that switch to sustainable materials can enhance their reputation and meet growing consumer demand for eco-friendly products. For example, IKEA replaced polystyrene with mycelium packaging for fragile items, reducing waste and appealing to conscious shoppers. By prioritizing innovation over convenience, companies can lead the charge in combating plastic pollution while staying competitive in a green economy.

Floating Fungi: Exploring Mushroom Growth on Airborne Islands

You may want to see also

Carbon sequestration: Fungi store carbon, combating climate change

Fungi, often overlooked in the grand scheme of climate solutions, play a pivotal role in carbon sequestration. Mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, are particularly adept at capturing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. These fungi create extensive underground networks that not only enhance soil health but also act as long-term carbon sinks. Studies show that mycorrhizal networks can store up to 70% of the carbon absorbed by plants, locking it away in the soil for decades or even centuries. This natural process is a silent yet powerful tool in the fight against climate change.

To harness this potential, consider integrating mycorrhizal fungi into agricultural practices. Farmers can inoculate crop soils with specific fungal species like *Glomus intraradices* or *Laccaria bicolor* to boost carbon storage while improving crop yields. For home gardeners, adding mycorrhizal inoculants to soil when planting trees or vegetables can enhance carbon sequestration on a smaller scale. These fungi thrive in diverse ecosystems, so preserving natural habitats and reducing soil disturbance are equally important. By fostering fungal growth, we can turn agricultural lands and forests into more effective carbon sinks.

A comparative analysis reveals that fungal carbon sequestration outperforms many engineered solutions in terms of cost and scalability. Unlike carbon capture technologies, which require significant energy and infrastructure, fungi operate passively, powered by sunlight and organic matter. For instance, a single hectare of forest with healthy mycorrhizal networks can sequester up to 2.5 metric tons of carbon annually—equivalent to the emissions from driving a car for over 6,000 miles. This natural efficiency underscores the untapped potential of fungi in global carbon reduction strategies.

However, maximizing fungal carbon sequestration requires careful management. Overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides can disrupt mycorrhizal networks, reducing their effectiveness. To avoid this, adopt organic farming practices that promote soil biodiversity. Additionally, reforestation efforts should prioritize native tree species that form strong mycorrhizal associations. Policymakers can incentivize these practices through subsidies or carbon credits, ensuring that fungi become a cornerstone of climate mitigation efforts. By nurturing these microscopic allies, we can turn the tide against climate change.

Mushrooms for Bloating Relief: Natural Solutions to Ease Discomfort

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Food security: High-protein mushrooms offer sustainable, scalable nutrition

Mushrooms, often overlooked in the realm of sustainable agriculture, are emerging as a high-protein solution to global food security challenges. With a protein content rivaling that of meat—oyster mushrooms, for instance, contain approximately 30 grams of protein per 100 grams when dried—they offer a nutrient-dense alternative that requires a fraction of the resources. Unlike livestock, which demands vast amounts of water, land, and feed, mushrooms can grow vertically in controlled environments, making them scalable even in urban settings. This efficiency positions them as a critical tool in feeding a growing global population while minimizing environmental impact.

Consider the practicalities of integrating mushrooms into diets: a single serving of shiitake mushrooms provides 2-3 grams of protein, comparable to an egg. For families in resource-scarce regions, cultivating mushrooms on agricultural waste like straw or sawdust can yield a steady protein source within weeks. In schools, incorporating mushroom-based meals—such as lentil and mushroom stews—can address malnutrition in children aged 5–12, a critical demographic for cognitive development. Pairing mushrooms with legumes enhances protein quality, ensuring all essential amino acids are present, a strategy already adopted in communities across Southeast Asia and Africa.

Scaling mushroom production requires addressing logistical hurdles. Smallholder farmers can start with low-cost methods like bag cultivation, using pasteurized substrate inoculated with spawn. For larger operations, vertical farming systems with LED lighting and humidity control maximize yield per square meter. Governments and NGOs can play a role by subsidizing spawn distribution and training programs, particularly in regions prone to food insecurity. A pilot project in India, for example, increased household protein intake by 40% through mushroom cultivation, demonstrating replicable success.

Critics may argue that mushrooms alone cannot solve food security, but their role as a complementary protein source is undeniable. Their rapid growth cycle—some varieties mature in 7–14 days—and ability to thrive on organic waste make them uniquely adaptable. By diversifying diets with mushrooms, societies can reduce reliance on resource-intensive animal agriculture while building resilience against climate-induced crop failures. As the world seeks sustainable nutrition solutions, mushrooms stand out not as a panacea, but as a scalable, protein-rich pillar in the fight against hunger.

Do Mushrooms Release Oxygen? Exploring Their Role in Ecosystems

You may want to see also

Biodegradable leather: Mushroom leather alternatives reduce environmental impact

The fashion industry's environmental footprint is staggering, with conventional leather production contributing significantly to deforestation, water pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. Enter mushroom leather, a biodegradable alternative that’s turning heads in sustainable fashion circles. Derived from mycelium, the root structure of fungi, this material mimics the texture and durability of animal leather without the ethical or ecological drawbacks. Brands like MycoWorks and Bolt Threads are already partnering with luxury designers to bring mushroom leather handbags, shoes, and jackets to market, proving that style and sustainability can coexist.

To understand the process, imagine a simple, nature-driven system: mycelium is grown in a lab on agricultural waste like sawdust or hemp, forming a dense, leather-like mat within weeks. Unlike animal leather, which requires toxic tanning chemicals and vast amounts of water, mushroom leather uses minimal resources and is fully biodegradable. When discarded, it decomposes in a matter of weeks, returning nutrients to the soil rather than clogging landfills. For consumers, this means guilt-free fashion—a pair of mushroom leather boots, for instance, could outlast synthetic alternatives while leaving a lighter ecological footprint.

Adopting mushroom leather isn’t just an eco-friendly choice; it’s a practical one. Studies show that mycelium-based materials can match or exceed the tensile strength and flexibility of traditional leather, making them suitable for high-wear items. However, challenges remain. Scaling production to meet global demand requires significant investment in research and infrastructure. Consumers can support this transition by prioritizing brands that use mushroom leather and advocating for policies that incentivize sustainable materials.

For those looking to make the switch, start small: opt for mushroom leather accessories like wallets or belts before committing to larger items. Check product labels for certifications like USDA BioPreferred or Cradle to Cradle, ensuring the material is genuinely sustainable. While mushroom leather may currently carry a premium price tag, its long-term benefits—both for the planet and personal style—make it a worthwhile investment. As the technology advances, this innovative material could redefine luxury, proving that fashion’s future is as much about responsibility as it is about aesthetics.

Mushrooms and Hair Loss: Unraveling the Surprising Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While mushrooms alone cannot "save the planet," they have significant potential to address environmental challenges. Mycelium, the root structure of mushrooms, can break down pollutants, replace plastic with biodegradable materials, and improve soil health, contributing to sustainability.

Mushrooms can sequester carbon by decomposing organic matter and storing it in the soil. Additionally, mycelium-based materials can replace carbon-intensive products like plastic and leather, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Yes, certain mushrooms, through a process called mycoremediation, can absorb and break down toxins like oil, heavy metals, and pesticides, helping to restore contaminated environments.

Absolutely. Mycelium can be grown into durable, biodegradable materials that mimic plastic, foam, and leather, offering eco-friendly alternatives to reduce plastic waste and pollution.

Mushrooms improve soil health by enhancing nutrient cycling and water retention. They can also be used as natural pesticides and fertilizers, reducing the need for chemical inputs in farming.