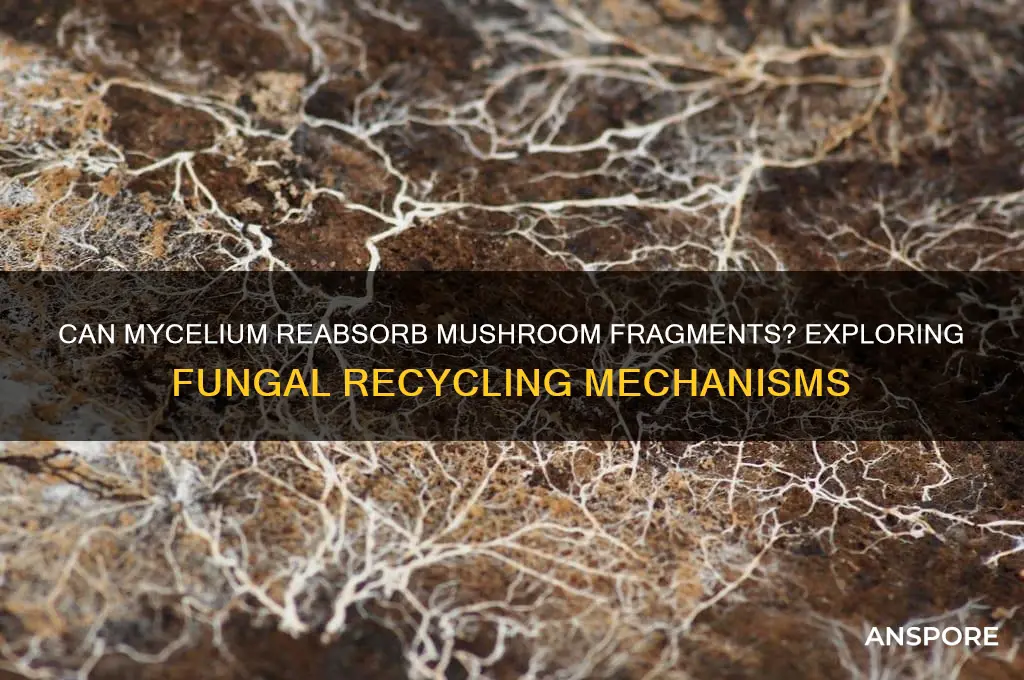

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus consisting of a network of fine white filaments, plays a crucial role in the life cycle of mushrooms. As the primary nutrient-absorbing structure, mycelium not only decomposes organic matter but also supports the growth and development of mushrooms. An intriguing aspect of this relationship is the ability of mycelium to reabsorb bits of mushroom tissue under certain conditions. This process, often observed in nature, allows the fungus to recycle nutrients from decaying or damaged mushroom parts, ensuring efficient resource utilization. Understanding this mechanism sheds light on the remarkable adaptability and sustainability of fungal ecosystems, highlighting the intricate interplay between mycelium and its fruiting bodies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reabsorption Capability | Mycelium can reabsorb parts of mushrooms under certain conditions, primarily when the mushroom tissue is damaged or senescent. |

| Purpose | Reabsorption allows mycelium to recycle nutrients, conserve resources, and maintain energy efficiency within the fungal network. |

| Mechanism | The process involves the breakdown of mushroom tissue by enzymes secreted by the mycelium, followed by nutrient reuptake. |

| Conditions for Reabsorption | Occurs more readily in environments with limited nutrients or when the mushroom is no longer viable (e.g., post-spore release or physical damage). |

| Species Variability | Not all fungal species exhibit this behavior; it is more common in saprotrophic and wood-decaying fungi. |

| Ecological Significance | Enhances fungal survival in nutrient-poor environments and contributes to nutrient cycling in ecosystems. |

| Research Status | While observed, the exact mechanisms and triggers for reabsorption are still areas of ongoing research. |

| Practical Applications | Understanding this process could inform mycoremediation, sustainable agriculture, and fungal biotechnology. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mycelium's Role in Nutrient Cycling

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, operates as a subterranean network that plays a pivotal role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems. Unlike plants, which rely on photosynthesis, mycelium extracts nutrients from organic matter through enzymatic breakdown. This process not only decomposes dead material but also redistributes essential elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon throughout the soil. For instance, when a mushroom cap or stem falls apart, mycelium can reabsorb these fragments, reclaiming nutrients to sustain its growth and metabolic functions. This ability underscores its efficiency in minimizing waste and maximizing resource utilization.

Consider the practical implications of this nutrient cycling for gardening and agriculture. By incorporating mycelium-rich compost or fungal inoculants into soil, gardeners can enhance nutrient availability for plants. A study published in *Nature Microbiology* highlights that mycelium networks can increase soil phosphorus uptake by up to 70% in agricultural systems. To implement this, mix 10–20% mycelium-infused substrate into your soil bed, ensuring even distribution. Avoid over-tilling, as this can disrupt the delicate fungal networks. For best results, monitor soil pH (optimal range: 6.0–7.0) and moisture levels, as mycelium thrives in slightly acidic, damp conditions.

From a comparative perspective, mycelium’s nutrient cycling efficiency outpaces that of bacteria in certain environments. While bacteria decompose organic matter rapidly, mycelium excels in breaking down complex compounds like lignin and chitin, which are resistant to bacterial action. This complementary relationship between fungi and bacteria creates a balanced ecosystem where nutrients are cycled more comprehensively. For example, in forest ecosystems, mycelium networks can span acres, connecting trees and facilitating the transfer of nutrients from decaying logs to living roots. This symbiotic process, known as the "wood wide web," highlights mycelium’s role as a keystone species in nutrient distribution.

Persuasively, understanding mycelium’s role in nutrient cycling offers a sustainable solution to modern agricultural challenges. Synthetic fertilizers, while effective, contribute to soil degradation and environmental pollution. In contrast, harnessing mycelium’s natural processes can improve soil health, reduce chemical dependency, and promote long-term fertility. Farmers in regions like the Pacific Northwest have already adopted mycelium-based practices, reporting increased crop yields and reduced pest incidence. By embracing this approach, we can shift toward regenerative agriculture, ensuring food security while preserving ecological balance.

Descriptively, imagine a forest floor teeming with life, where mycelium threads weave through the soil like a hidden tapestry. As leaves, twigs, and even mushroom remnants fall, these threads envelop them, secreting enzymes to unlock their nutrients. This subterranean alchemy transforms decay into vitality, fueling the growth of plants, microbes, and fungi alike. Observing this process, one grasps the elegance of nature’s design—a system where nothing is wasted, and every element serves a purpose. Mycelium’s role in nutrient cycling is not just functional; it is poetic, a testament to the interconnectedness of life.

Can Mushrooms Thrive on Mars? Exploring Fungal Survival in Space

You may want to see also

Reabsorption Mechanisms in Fungi

Fungi exhibit a remarkable ability to reabsorb parts of their fruiting bodies, such as mushrooms, through intricate mechanisms tied to their mycelial networks. This process, often triggered by environmental stressors or nutrient depletion, allows fungi to recycle resources efficiently. For instance, when a mushroom is damaged or begins to senesce, the mycelium can detect this through chemical signals, initiating the reabsorption of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. This adaptive strategy ensures survival in nutrient-poor environments, highlighting the mycelium’s role as both builder and recycler within the fungal ecosystem.

To understand reabsorption, consider the steps involved: first, the mycelium senses the compromised mushroom via signaling molecules like autoinducers. Next, it redirects enzymes and transport proteins to the site, breaking down cellular components into reusable forms. For example, chitinases degrade the mushroom’s chitinous cell walls, while proteases target proteins. These nutrients are then transported back to the mycelium via hyphae, where they are stored or used for growth. Practical observation of this process can be facilitated by monitoring mushrooms in controlled environments, noting changes in color, texture, and mass over time.

A comparative analysis reveals that reabsorption mechanisms vary across fungal species. Saprotrophic fungi, like *Coprinopsis cinerea*, are adept at rapid reabsorption, often dissolving their caps within hours under stress. In contrast, mycorrhizal fungi, such as *Amanita muscaria*, may reabsorb more slowly, prioritizing nutrient retention for their symbiotic partners. This diversity underscores the evolutionary tailoring of reabsorption to specific ecological niches. For hobbyists or researchers, documenting these differences can provide insights into fungal behavior and potential biotechnological applications.

Persuasively, the study of fungal reabsorption holds untapped potential for sustainable agriculture and waste management. By mimicking these mechanisms, we could develop systems for nutrient recycling in crop cultivation or bio-remediation. For instance, mycelium-based filters could reabsorb pollutants, much like they reclaim mushroom tissue. Implementing such solutions requires interdisciplinary collaboration, but the payoff—reduced waste and enhanced resource efficiency—is compelling. Start small: experiment with fungal cultures in lab settings to observe reabsorption firsthand and contribute to this growing field.

Finally, a descriptive exploration of reabsorption reveals its elegance and complexity. Picture a network of hyphae, thin as threads, extending like roots beneath the soil. When a mushroom above withers, the mycelium responds with precision, deploying enzymes like a surgical team dismantling a structure. Nutrients flow back through the network, a silent, subterranean economy. This process, though hidden, is a testament to fungi’s resilience and ingenuity, offering lessons in efficiency and adaptability that transcend biology. Observe it closely, and you’ll see not just decay, but renewal.

Exploring Astral Projection: Can Mushrooms Unlock Out-of-Body Experiences?

You may want to see also

Conditions for Mycelium Reabsorption

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, exhibits a remarkable ability to reabsorb parts of its fruiting bodies—mushrooms—under specific conditions. This process, often triggered by environmental stressors or resource scarcity, allows the organism to recycle nutrients and conserve energy. For reabsorption to occur, the mycelium must detect that the mushroom is no longer viable or beneficial, such as when it is damaged, dehydrated, or has completed its spore-releasing function. Understanding these conditions provides insight into fungal survival strategies and offers practical applications in cultivation and conservation.

Environmental Triggers and Optimal Conditions

Reabsorption is most likely to occur in environments where the mycelium perceives a threat to its survival or an opportunity to redirect resources. Low humidity, for instance, can signal water scarcity, prompting the mycelium to reclaim nutrients from the mushroom. Similarly, physical damage to the mushroom, such as breakage or insect predation, may initiate reabsorption as the mycelium prioritizes internal resource allocation. Optimal conditions for this process include a stable substrate with sufficient organic matter, moderate temperatures (typically 18–24°C), and minimal light exposure. Cultivators can mimic these conditions by maintaining consistent moisture levels and avoiding abrupt environmental changes.

Nutrient Availability and Resource Management

The decision to reabsorb mushroom tissue is closely tied to nutrient availability in the surrounding substrate. When the mycelium detects a lack of essential nutrients like nitrogen or phosphorus, it may redirect resources from the mushroom back into its network. This behavior is particularly evident in species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom), which efficiently recycles nutrients in nutrient-poor environments. To encourage reabsorption in cultivation, reduce external nutrient inputs once mushrooms have matured, allowing the mycelium to prioritize internal recycling. However, avoid complete nutrient deprivation, as this can stress the organism and hinder overall growth.

Practical Tips for Observing and Inducing Reabsorption

For those interested in observing mycelium reabsorption, start by cultivating mushrooms in a controlled environment. After harvesting mature mushrooms, leave behind small, damaged, or incomplete fruiting bodies. Monitor the substrate over 7–14 days, maintaining humidity at 60–70% and avoiding direct sunlight. Document changes in mushroom appearance, such as shrinking or color fading, which indicate reabsorption. To induce the process, gently damage the mushroom’s cap or stem, mimicking natural stressors. This technique is particularly useful in educational settings or for studying fungal behavior.

Comparative Analysis and Takeaway

While mycelium reabsorption is a natural process, its efficiency varies across species. For example, *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) shows slower reabsorption rates compared to *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake), which rapidly recycles nutrients under stress. This variation highlights the importance of species-specific conditions for optimal reabsorption. The takeaway is clear: understanding and manipulating these conditions not only enhances our knowledge of fungal ecology but also improves cultivation practices, reducing waste and maximizing resource use in both natural and artificial systems.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Sand? Exploring Unconventional Growing Mediums

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Mushroom Growth Stages

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, plays a pivotal role in nutrient cycling and mushroom development. When bits of a mushroom are broken off or decay, mycelium can indeed reabsorb these fragments, redirecting nutrients back into the fungal network. This process is particularly evident during the maturation stage of mushroom growth, where fallen or damaged fruiting bodies decompose and are reclaimed by the mycelium. For cultivators, this means that minor losses during harvesting or accidental damage do not necessarily equate to wasted resources. However, the efficiency of reabsorption depends on environmental conditions like humidity (optimal at 60-70%) and temperature (20-25°C), which must be maintained to support this regenerative process.

During the spawn run stage, mycelium colonizes the substrate, forming a dense network of hyphae. If mushroom fragments are introduced at this stage—whether intentionally or accidentally—the mycelium can integrate these bits, accelerating colonization by providing additional nutrients. For instance, adding finely chopped mushroom remnants (10-15% by weight of the substrate) can enhance mycelial growth rates by up to 20%. However, caution is necessary: larger fragments or excessive amounts can introduce contaminants or disrupt the substrate’s structure, hindering rather than aiding growth. This technique is especially useful in low-nutrient substrates, where every organic input counts.

The pinning stage, where primordia (baby mushrooms) first emerge, is sensitive to environmental and nutritional cues. If mycelium reabsorbs mushroom fragments during this phase, it can redirect resources away from primordia development, potentially delaying fruiting. Conversely, in cases of nutrient deficiency, reabsorption of small fragments can provide a critical nutrient boost, supporting healthy pin formation. Cultivators should monitor this stage closely, ensuring that any reabsorption activity does not compete with the energy demands of fruiting. Maintaining a balanced substrate-to-mycelium ratio (e.g., 1:3 by volume) can mitigate this risk while allowing for efficient nutrient recycling.

In the fruiting stage, reabsorption of mushroom bits is less common but still possible, particularly if mushrooms are damaged or overripe. While this process can free up nutrients for new flushes, it may also signal suboptimal growing conditions, such as inadequate airflow or light. To encourage multiple flushes, cultivators should remove spent or decaying mushrooms promptly, preventing reabsorption that could otherwise divert energy from new growth. For example, in oyster mushroom cultivation, removing mature fruiting bodies within 48 hours of sporulation can increase the likelihood of a second flush by 30-40%.

Finally, during the senescence stage, when mushrooms age and decompose, reabsorption by mycelium becomes a natural part of the fungal life cycle. This stage is critical for nutrient recovery, as the mycelium breaks down spent fruiting bodies and recycles their components. For outdoor cultivators, leaving decomposing mushrooms in place can enrich the soil and support future growth cycles. However, in controlled environments, removing decomposing material is essential to prevent mold or bacterial contamination. Striking this balance ensures that reabsorption serves as a regenerative process rather than a source of decay.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Partially Colonized Jars? Growing Tips

You may want to see also

Ecological Benefits of Reabsorption

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, exhibits a remarkable ability to reabsorb parts of mushrooms, a process that plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems. This reabsorption mechanism allows mycelium to reclaim essential elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon from decaying mushroom tissue, effectively minimizing waste and maximizing resource efficiency. By breaking down and reintegrating these nutrients, mycelium supports the health of surrounding soil and plant life, fostering a more resilient and productive environment.

Consider the forest floor, where mushrooms often sprout, grow, and decay in a matter of days. When mycelium reabsorbs mushroom fragments, it prevents the accumulation of organic matter that could otherwise lead to nutrient imbalances. For instance, in a study published in *Ecology*, researchers observed that mycelium networks in temperate forests reabsorbed up to 30% of mushroom biomass within 48 hours of decay initiation. This rapid recycling ensures that nutrients remain available for other organisms, from bacteria to trees, creating a dynamic and balanced ecosystem.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this process can inform sustainable practices in agriculture and forestry. For example, farmers can encourage mycelium growth by incorporating fungal inoculants into soil, enhancing nutrient retention and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. In permaculture systems, planting mycelium-rich substrates around crops can create a natural nutrient reservoir, particularly beneficial for long-term soil health. A key tip: avoid tilling in areas with active mycelium networks, as this disrupts the fungal structures and hinders their reabsorption capabilities.

Comparatively, ecosystems lacking robust mycelium networks often suffer from slower nutrient cycling and reduced biodiversity. In disturbed habitats, such as clear-cut forests or over-tilled fields, the absence of mycelium leads to nutrient leaching and soil degradation. By contrast, intact mycelium networks act as ecological glue, holding soil particles together and preventing erosion while facilitating nutrient reabsorption. This highlights the importance of preserving fungal habitats in conservation efforts.

Finally, the reabsorption process underscores the interconnectedness of life in ecosystems. Mycelium not only sustains itself but also supports a web of organisms, from microbes to megafauna, by ensuring a steady supply of nutrients. This ecological service is particularly vital in nutrient-limited environments, such as boreal forests or arid grasslands, where efficient nutrient cycling is essential for survival. By recognizing and protecting mycelium’s role, we can foster healthier, more sustainable ecosystems for future generations.

Can Mushrooms Grow on Mushrooms? Exploring Fungal Growth Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mycelium can reabsorb parts of mushrooms, especially when they are damaged, diseased, or no longer viable. This process helps the fungus recycle nutrients and conserve energy.

Mycelium reabsorbs mushroom tissue to reclaim nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon, which can be redirected to support new growth or other parts of the fungal network.

Typically, mycelium does not reabsorb fully mature mushrooms unless they are damaged or decaying. Healthy, mature mushrooms are left to release spores for reproduction.

The speed of reabsorption depends on factors like the size of the mushroom fragment, environmental conditions, and the health of the mycelium. It can take hours to days for noticeable reabsorption to occur.