The Archaea domain, one of the three primary domains of life, comprises ancient microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments, such as hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, and highly saline habitats. Unlike bacteria and eukaryotes, archaea have unique cellular structures and metabolic pathways, raising questions about their reproductive mechanisms. While some archaea reproduce through binary fission, similar to bacteria, the ability to form spores—a dormant, resilient cell type—has been a topic of scientific inquiry. Spores are typically associated with bacteria and fungi, serving as survival structures in harsh conditions. However, recent research suggests that certain archaea, particularly those in the genus *Halobacterium*, may produce spore-like structures under stress. These structures, though not identical to bacterial spores, exhibit similar protective functions, enabling archaea to endure extreme environments. Thus, while not all archaea reproduce via spores, some species appear to have evolved spore-like mechanisms to ensure survival in their challenging habitats.

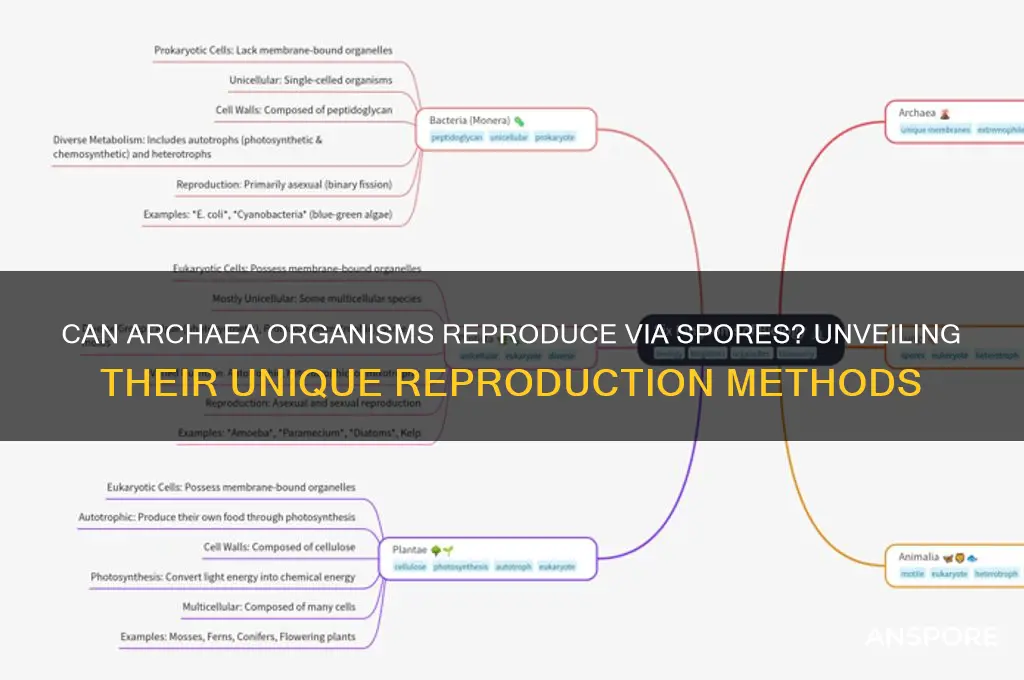

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction via Spores | No, organisms in the Archaea domain do not reproduce via spores. |

| Reproduction Methods | Primarily asexual reproduction through binary fission, fragmentation, or budding. |

| Sporulation Ability | Unlike some Bacteria (e.g., Bacillus), Archaea lack the genetic and cellular mechanisms for sporulation. |

| Survival Strategies | Form cysts or biofilms for protection in harsh environments (e.g., extreme temperatures, salinity). |

| Genetic Exchange | Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) via conjugation, transformation, or transduction, but not spore-mediated transfer. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Pseudopeptidoglycan or other unique polymers, distinct from bacterial spore structures. |

| Environmental Adaptations | Thrive in extreme habitats (thermophiles, halophiles, acidophiles) without relying on spore formation. |

| Notable Exceptions | No known Archaea species produce spores; research confirms absence of sporulation genes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporulation mechanisms in Archaea

Archaea, one of the three domains of life, are renowned for their ability to thrive in extreme environments, from hydrothermal vents to highly saline lakes. While sporulation is a well-documented survival strategy in bacteria, its occurrence in Archaea has been a subject of scientific inquiry. Recent studies suggest that certain archaeal species can indeed form spore-like structures, though the mechanisms differ significantly from those in bacteria. These structures, often termed "cysts" or "resting cells," serve as protective forms that enhance survival under harsh conditions. Understanding these sporulation mechanisms not only sheds light on archaeal resilience but also has implications for astrobiology and biotechnology.

One notable example is *Halobacterium salinarum*, a halophilic archaeon that forms cyst-like structures in response to nutrient deprivation. These structures are characterized by a thickened cell wall and reduced metabolic activity, enabling long-term survival in hypersaline environments. Unlike bacterial spores, which involve a complex process of endospore formation, archaeal sporulation appears to be a simpler, more rapid adaptation. The process is triggered by environmental stressors such as desiccation or high salinity, with cells undergoing morphological changes within hours. This rapid response underscores the efficiency of archaeal survival strategies in dynamic ecosystems.

From a mechanistic perspective, archaeal sporulation involves the upregulation of genes associated with cell wall synthesis and stress response. For instance, genes encoding S-layer proteins, which form the outermost layer of the archaeal cell wall, are overexpressed during sporulation. Additionally, studies have identified heat shock proteins and DNA repair enzymes that play a crucial role in maintaining cellular integrity under stress. While the exact molecular pathways remain under investigation, it is clear that archaeal sporulation is a highly coordinated process that prioritizes cellular preservation over replication.

Practical applications of archaeal sporulation mechanisms are emerging in biotechnology and astrobiology. For example, understanding how archaea form protective structures could inspire the development of novel preservation techniques for microorganisms in industrial processes. Moreover, the ability of archaea to survive in extreme conditions mirrors those found on other planets, making them prime candidates for studying potential extraterrestrial life. By deciphering the sporulation mechanisms in Archaea, scientists can gain insights into the limits of life and the strategies organisms employ to endure in the most inhospitable environments.

In conclusion, while archaeal sporulation differs from bacterial sporulation, it represents a unique and efficient survival mechanism tailored to the extreme niches these organisms inhabit. Continued research into this area promises to reveal not only the molecular intricacies of archaeal resilience but also practical applications that could revolutionize biotechnology and expand our understanding of life’s boundaries.

Dry Rot Spores: Uncovering Potential Health Risks and Concerns

You may want to see also

Types of spores produced by Archaea

Archaea, one of the three domains of life, are renowned for their ability to thrive in extreme environments, from hydrothermal vents to highly saline lakes. While many organisms in the Bacteria and Eukarya domains reproduce via spores, the question of whether Archaea produce spores has intrigued scientists for decades. Research indicates that certain Archaea, particularly those in the genus *Halobacterium*, form structures akin to endospores, though they differ significantly from bacterial spores in composition and function. These archaeal spores are not true endospores but rather highly resistant cells called cysts, which allow them to survive harsh conditions.

Analyzing the types of spores produced by Archaea reveals a unique adaptation to their environments. For instance, *Halobacterium salinarum* forms cysts in response to nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of phosphorus. These cysts are characterized by a thickened cell wall and reduced metabolic activity, enabling long-term survival in hypersaline environments. Unlike bacterial spores, which are typically heat-resistant, archaeal cysts are optimized for desiccation and osmotic stress resistance. This distinction highlights the specialized nature of archaeal spore-like structures, tailored to their specific ecological niches.

From a practical standpoint, understanding archaeal spore formation has implications for biotechnology and astrobiology. For example, the ability of *Halobacterium* to form cysts could inspire the development of preservation techniques for extremophile microorganisms in industrial processes. Additionally, studying these structures provides insights into potential life forms on other planets, where extreme conditions similar to those on Earth might exist. Researchers can mimic these environments in labs to induce cyst formation, using controlled nutrient deprivation and salinity levels to observe the process.

Comparatively, while bacterial spores are well-documented for their role in survival and dispersal, archaeal cysts remain less understood. Bacterial spores, such as those of *Bacillus subtilis*, are encased in multiple protective layers, including a proteinaceous coat and an outer exosporium. In contrast, archaeal cysts lack these complex layers but rely on a modified cell wall and altered lipid composition to withstand stress. This comparison underscores the evolutionary divergence in spore-like structures across domains, reflecting distinct survival strategies.

In conclusion, the types of spores produced by Archaea, though not true spores, represent a fascinating adaptation to extreme environments. From the cysts of *Halobacterium* to potential undiscovered structures in other archaeal species, these formations offer a window into the resilience of life. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can unlock new applications in biotechnology and deepen our understanding of life’s limits, both on Earth and beyond. Practical experiments, such as inducing cyst formation in controlled lab settings, can further illuminate these processes and their potential uses.

Can Bulbasaur Learn Stun Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore formation

Spore formation in Archaea, particularly in extremophiles like *Halobacteria*, is a survival strategy triggered by specific environmental cues. Unlike bacteria, Archaea do not typically form spores, but some species exhibit sporulation-like processes in response to stress. For instance, *Halobacterium salinarum* forms dormant cysts under nutrient deprivation, a mechanism akin to spore formation. These cysts are triggered by a lack of essential nutrients like phosphate or nitrogen, showcasing how resource scarcity directly induces a protective state. Understanding these triggers is crucial for studying Archaea’s resilience in extreme habitats, such as salt flats or deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

Analyzing the role of salinity and pH shifts reveals another layer of environmental triggers. Archaea in hypersaline environments, such as *Haloarchaea*, often face rapid changes in salt concentration. A sudden increase in salinity beyond their optimal range (typically 15–25% NaCl) can induce spore-like structures. Similarly, extreme pH fluctuations—either highly acidic or alkaline conditions—activate stress responses leading to dormancy. For example, *Thermoplasma acidophilum* responds to pH levels below 2 by halting metabolic activity and forming protective aggregates. These responses highlight how Archaea use environmental extremes as cues to initiate survival mechanisms.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to biotechnology and astrobiology. By mimicking environmental triggers in lab settings, researchers can induce spore-like states in Archaea for preservation or study. For instance, exposing *Haloferax volcanii* to 30% NaCl for 48 hours consistently triggers cyst formation, which can later be revived under optimal conditions. This technique is valuable for long-term storage of extremophiles or for simulating extraterrestrial conditions, as Archaea’s resilience mirrors potential life forms on Mars or Europa. Understanding these triggers also aids in predicting how Archaea respond to climate change, such as shifting salinity in oceans or increased acidification.

Comparing Archaea’s spore-like mechanisms to those in bacteria reveals both similarities and unique adaptations. While bacterial spores (e.g., *Bacillus*) rely on heat, desiccation, or nutrient depletion, Archaea’s triggers are often tied to their specific extremophile niches. For example, thermophilic Archaea like *Pyrococcus furiosus* may form dormant states under sudden temperature drops below 80°C, a stark contrast to their optimal 100°C growth. This niche-specificity underscores the importance of tailoring environmental triggers to the organism’s habitat. Such comparisons not only deepen our understanding of microbial survival but also inspire biomimetic technologies for extreme conditions.

In conclusion, environmental triggers for spore-like formation in Archaea are finely tuned to their extreme habitats, ranging from nutrient deprivation to salinity and pH shifts. These mechanisms not only ensure survival but also offer practical insights for biotechnology and astrobiology. By studying these triggers, we unlock the secrets of Archaea’s resilience and their potential applications in industries and space exploration. Whether in a lab or on another planet, understanding these cues is key to harnessing the power of extremophiles.

Can Concrobium Effectively Kill C-Diff Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in Archaea survival

Archaea, one of the three domains of life, are renowned for their ability to thrive in extreme environments, from scorching hot springs to highly saline lakes. While not all archaea reproduce via spores, certain species within this domain have evolved this mechanism as a survival strategy. Spores are highly resistant, dormant structures that enable organisms to endure harsh conditions, such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, and radiation. For archaea, spore formation is particularly crucial in environments where resources are scarce or conditions fluctuate dramatically. This adaptive feature allows them to persist in a state of suspended animation until more favorable conditions return.

Consider the example of *Halobacterium salinarum*, an archaeon found in hypersaline environments. While it does not form spores, its close relative *Haloarcula vallismortis* has been studied for its ability to produce spore-like structures under stress. These structures provide a protective barrier against osmotic shock and UV radiation, ensuring survival in salt-saturated habitats. Similarly, thermophilic archaea like *Sulfolobus* species, which inhabit hot springs, may enter a dormant state akin to sporulation when nutrients are depleted. This dormancy is not identical to bacterial sporulation but serves a comparable purpose: long-term survival in adverse conditions.

The process of spore formation in archaea, though less studied than in bacteria, involves metabolic slowdown and the synthesis of protective molecules like trehalose and proteins resistant to denaturation. These adaptations allow spores to withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C, pH levels as low as 0, and radiation doses lethal to most life forms. For instance, spores of extremophilic archaea can survive exposure to ionizing radiation at doses up to 5,000 Gy, compared to the 10 Gy limit for most eukaryotic cells. This resilience is critical for their persistence in environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents and arid deserts.

From a practical standpoint, understanding archaeal spore mechanisms has implications for biotechnology and astrobiology. Spores’ resistance to extreme conditions makes them valuable for industrial applications, such as enzyme stability in high-temperature manufacturing processes. Additionally, their ability to endure radiation and desiccation fuels speculation about the potential for life on Mars, where similar conditions exist. Researchers are exploring archaeal spores as models for extraterrestrial survival, with experiments simulating Martian conditions showing that some spores remain viable after prolonged exposure to low pressure, UV radiation, and freezing temperatures.

In conclusion, while not all archaea reproduce via spores, those that do leverage this strategy to dominate some of Earth’s most inhospitable niches. By forming spores, these organisms ensure genetic continuity across generations, even in environments where active growth is impossible. This survival mechanism not only highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of archaea but also offers insights into the limits of life and its potential beyond our planet. Studying archaeal spores expands our understanding of biological resilience and inspires innovations in fields ranging from biotechnology to space exploration.

How Long Do Spore Prints Last: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Comparison with bacterial spore reproduction

Archaea and bacteria, though both prokaryotic, diverge significantly in their reproductive strategies, particularly when it comes to spore formation. While bacterial spore reproduction is well-documented, archaeal organisms do not produce spores in the same manner. Bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, form endospores—highly resistant structures that allow them to survive extreme conditions like heat, desiccation, and radiation. These spores are metabolically dormant and can persist for years until conditions become favorable for germination. In contrast, archaea lack this spore-forming capability, relying instead on other mechanisms to endure harsh environments, such as robust cell walls and unique lipid compositions.

To understand the implications of this difference, consider the environments in which these organisms thrive. Bacteria often inhabit transiently harsh habitats, where spore formation provides a survival advantage. Archaea, however, dominate extreme and stable environments like hydrothermal vents, salt lakes, and acidic hot springs. Their survival strategies focus on cellular adaptations rather than spore production. For instance, some archaea produce ether-linked lipids, which maintain membrane integrity under extreme temperatures and pressures. This fundamental distinction highlights how evolutionary pressures shape reproductive and survival mechanisms in these domains.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in archaea has significant implications for biotechnology and environmental studies. Bacterial spores are notorious for their resilience, posing challenges in food preservation, medical sterilization, and industrial processes. Archaea, despite their extremophile nature, do not present the same spore-related concerns. Researchers can exploit this difference by targeting archaeal organisms in applications where spore contamination is problematic, such as in biofuel production or bioremediation. Understanding these reproductive differences allows for more precise manipulation of microbial communities in various industries.

A comparative analysis reveals that while bacterial spores are a specialized survival strategy, archaea’s approach is more about enduring adversity in real-time. For example, *Halobacteria*, an archaeal genus, survives in high-salt environments by accumulating potassium ions internally, a mechanism unrelated to spore formation. This contrasts with *Bacillus subtilis*, which forms spores to withstand similar osmotic stresses. Such comparisons underscore the diversity of prokaryotic survival strategies and the importance of context in evaluating reproductive adaptations.

In conclusion, the comparison between archaeal and bacterial reproductive strategies highlights a critical divergence in how these domains respond to environmental challenges. While bacterial spores are a testament to the power of dormancy, archaea’s reliance on cellular robustness showcases an alternative evolutionary path. This distinction not only enriches our understanding of microbial life but also informs practical applications in fields ranging from biotechnology to astrobiology. By focusing on these differences, scientists can better harness the unique capabilities of archaea and bacteria in addressing real-world problems.

Exploring Rhizopus Sporangium: Unveiling the Presence of Spores Within

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, organisms in the Archaea domain do not reproduce with spores. Spores are primarily associated with certain bacteria and fungi, not archaea.

Archaea do not form spores, but some species can produce cyst-like structures or dormant cells under extreme environmental conditions, though these are not true spores.

Archaea reproduce asexually through binary fission, fragmentation, or budding, depending on the species, and do not rely on spore formation for reproduction.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)