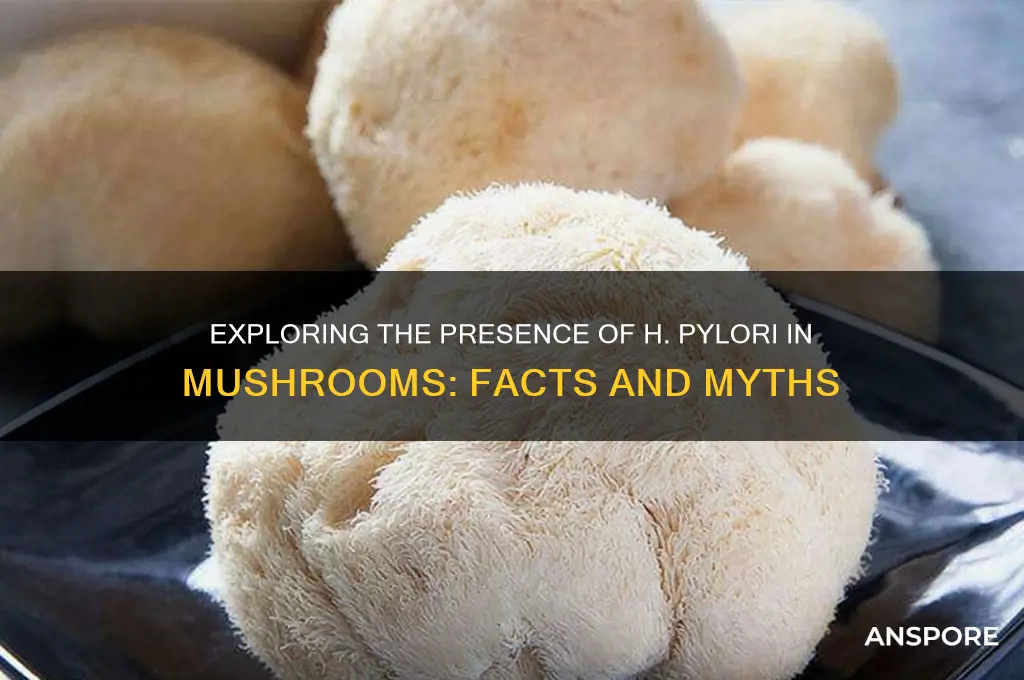

The question of whether *Helicobacter pylori* (*H. pylori*), a bacterium known to cause stomach ulcers and other gastrointestinal issues, can be found in mushrooms has sparked curiosity and debate. While *H. pylori* primarily resides in the human stomach and is typically transmitted through contaminated food, water, or person-to-person contact, there is limited scientific evidence directly linking its presence to mushrooms. Mushrooms, being fungi, grow in environments that are not typically conducive to harboring *H. pylori*, which thrives in acidic conditions. However, contamination during handling, storage, or preparation could theoretically introduce the bacterium to mushrooms. To date, no widespread studies have confirmed *H. pylori* in mushrooms, but proper hygiene and food safety practices remain essential to minimize the risk of bacterial contamination in any food source.

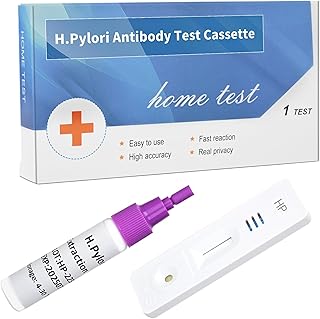

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushroom Species and H. Pylori

Observation: While *Helicobacter pylori* (*H. pylori*) is primarily associated with human gastric infections, its presence in environmental sources, including mushrooms, has sparked curiosity. Certain mushroom species, particularly those growing in contaminated soil or near animal habitats, have been investigated for potential *H. pylori* colonization. For instance, wild mushrooms like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushrooms) and *Boletus edulis* (porcini) have been studied for their microbial content, though conclusive evidence of *H. pylori* remains limited.

Analytical Insight: The likelihood of *H. pylori* in mushrooms hinges on their growing conditions. Mushrooms are bioaccumulative, absorbing microorganisms from their environment. Studies suggest that mushrooms cultivated in regions with poor sanitation or near livestock may harbor pathogens, including *H. pylori*. However, commercial mushrooms grown in controlled environments are less likely to carry such bacteria. A 2018 study in *Food Control* found trace levels of *H. pylori* DNA in wild mushrooms, but viable bacteria were not detected, indicating minimal risk from consumption.

Practical Tips: To minimize potential exposure, avoid consuming raw wild mushrooms, especially those harvested from areas with known contamination. Thoroughly cooking mushrooms at temperatures above 60°C (140°F) for at least 10 minutes can eliminate most pathogens, including *H. pylori*. Foraging enthusiasts should also wear gloves and clean tools to prevent cross-contamination. If you suspect gastrointestinal symptoms after consuming mushrooms, consult a healthcare provider for *H. pylori* testing, as symptoms like bloating, nausea, or stomach pain may overlap with mushroom-related illnesses.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike *H. pylori*, other bacteria like *E. coli* and *Salmonella* are more commonly found in contaminated mushrooms. *H. pylori*’s acid-resistant nature makes it less likely to survive outside the human stomach for extended periods. In contrast, mushrooms are more prone to carrying soil-borne pathogens. This distinction highlights the importance of focusing on broader food safety practices rather than *H. pylori* specifically when handling mushrooms.

Takeaway: While *H. pylori* in mushrooms is theoretically possible, particularly in wild varieties from high-risk environments, the risk is negligible for most consumers. Adhering to proper hygiene, cooking methods, and sourcing mushrooms from reputable suppliers can effectively mitigate any potential health concerns. Research remains inconclusive, but current evidence suggests that *H. pylori* transmission via mushrooms is not a significant public health issue.

Psilocybin vs. Deadly Mushrooms: How to Safely Identify the Difference

You may want to see also

Contamination Sources in Mushrooms

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their nutritional benefits and culinary versatility, are not immune to contamination. One of the primary sources of contamination in mushrooms is their growing environment. Mushrooms are natural absorbers, readily soaking up substances from their surroundings, including soil, water, and air. This unique characteristic makes them particularly vulnerable to contaminants like heavy metals, pesticides, and bacteria. For instance, mushrooms cultivated in soil contaminated with lead or cadmium can accumulate these metals to levels that pose health risks when consumed. Similarly, wild mushrooms growing in areas treated with pesticides or near industrial sites may harbor residues that are harmful to humans.

Another significant contamination source is improper handling and storage during harvesting and post-harvest processes. Mushrooms are highly perishable and require careful handling to prevent bacterial growth. Cross-contamination from unsanitary equipment, surfaces, or hands can introduce pathogens such as *E. coli* or *Salmonella*. Additionally, inadequate refrigeration or exposure to moisture can create conditions conducive to mold growth, rendering the mushrooms unsafe for consumption. Farmers and distributors must adhere to strict hygiene protocols, including regular cleaning of tools, wearing protective gear, and maintaining optimal storage conditions to minimize these risks.

Water quality plays a critical role in mushroom contamination, especially in commercial cultivation. Mushrooms require a significant amount of water during growth, and if the water source is contaminated with bacteria, parasites, or chemicals, these can be transferred to the mushrooms. For example, irrigation water tainted with *Helicobacter pylori* (H. pylori), a bacterium commonly associated with stomach ulcers, could theoretically lead to contamination, though such cases are rare and not well-documented. To mitigate this risk, cultivators should test water sources regularly and use filtration systems to ensure it is free from harmful microorganisms and pollutants.

Lastly, the type of substrate used in mushroom cultivation can introduce contaminants. Substrates like straw, wood chips, or compost provide the nutrients mushrooms need to grow, but if these materials are not properly sterilized, they can harbor bacteria, fungi, or pests. For instance, compost contaminated with *H. pylori* or other pathogens could potentially transfer these microorganisms to the mushrooms. Cultivators should sterilize substrates using methods such as steam treatment or chemical disinfection to eliminate harmful organisms. By addressing these contamination sources, both growers and consumers can ensure that mushrooms remain a safe and healthy food choice.

Mushrooms and ED: Exploring Natural Remedies for Erectile Dysfunction

You may want to see also

H. Pylori Survival in Fungi

Observation: *Helicobacter pylori* (*H. pylori*), a bacterium notorious for colonizing the human stomach, has been detected in unexpected environments, including fungi. This raises questions about its survival mechanisms outside the host and potential transmission vectors.

Analytical Insight: Studies have identified *H. pylori* in mushroom samples, particularly those grown in contaminated soil or water. The bacterium’s ability to survive in fungi is attributed to its resilience in low-pH environments and biofilm formation. Fungi, with their complex structures and moisture retention, provide a protective niche for *H. pylori*, shielding it from environmental stressors. This symbiotic relationship suggests fungi could act as reservoirs, prolonging bacterial survival outside the human body.

Instructive Guidance: To minimize exposure, individuals should thoroughly wash mushrooms before consumption, especially if sourced from areas with poor sanitation. Boiling mushrooms for at least 10 minutes can reduce bacterial load, as *H. pylori* is heat-sensitive above 60°C. For immunocompromised individuals or those with a history of *H. pylori* infection, avoiding raw mushrooms is advisable.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike *H. pylori*’s survival in water or soil, fungi offer a more stable habitat due to their organic matter and moisture content. While soil contamination is transient, fungal colonization provides a persistent source of bacterial exposure. This distinction highlights the need for targeted food safety measures, particularly in mushroom cultivation and handling.

Persuasive Argument: The detection of *H. pylori* in fungi underscores the importance of reevaluating food safety protocols. Regulatory bodies should mandate testing for bacterial contamination in mushroom farms, especially in regions with high *H. pylori* prevalence. Public awareness campaigns can educate consumers on proper mushroom preparation, reducing the risk of inadvertent bacterial ingestion.

Practical Takeaway: While *H. pylori* in fungi is not a widespread concern, it serves as a reminder of the bacterium’s adaptability. Simple precautions, such as washing and cooking mushrooms thoroughly, can mitigate potential health risks. For researchers, this finding opens avenues to explore fungal-bacterial interactions and their implications for disease transmission.

Mushrooms and Digestion: Can Fungi Boost Your Bowel Movements?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health Risks of Infected Mushrooms

Observation: While *Helicobacter pylori* (*H. pylori*) is primarily associated with gastric infections in humans, its presence in mushrooms is a topic of emerging concern. Research indicates that contaminated soil and water can introduce *H. pylori* to mushrooms, particularly in regions with poor sanitation. This raises questions about the health risks associated with consuming infected mushrooms, especially for vulnerable populations.

Analytical Insight: The risk of *H. pylori* transmission via mushrooms lies in the bacterium’s ability to survive in damp, organic environments where mushrooms thrive. Studies have detected *H. pylori* DNA in wild mushrooms, suggesting potential contamination during growth. However, the viability of the bacteria post-harvest and after cooking remains uncertain. Raw or undercooked infected mushrooms pose a higher risk, as heat treatment above 60°C (140°F) for 10–15 minutes can effectively kill *H. pylori*. Individuals with compromised immune systems, such as the elderly or those with HIV, are more susceptible to infection, even from low bacterial loads.

Practical Steps: To minimize health risks, follow these precautions: 1) Source mushrooms from reputable suppliers who adhere to hygienic cultivation practices. 2) Thoroughly wash wild mushrooms to remove soil and potential contaminants. 3) Cook mushrooms at temperatures exceeding 60°C to ensure bacterial inactivation. 4) Avoid raw mushroom consumption, especially for children under 5 and adults over 65, who are at higher risk of complications from *H. pylori* infections.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike foodborne pathogens like *Salmonella* or *E. coli*, *H. pylori* in mushrooms is not a widespread issue but warrants attention due to its association with chronic conditions such as gastritis and ulcers. While contaminated water and raw vegetables are more common sources of *H. pylori*, mushrooms grown in unsanitary conditions could serve as a niche transmission route. This highlights the importance of agricultural hygiene in preventing bacterial contamination across food sources.

Takeaway: While the risk of contracting *H. pylori* from mushrooms is relatively low, it is not negligible, particularly in regions with poor sanitation. By adopting safe handling and cooking practices, consumers can significantly reduce their exposure to this bacterium. Awareness and proactive measures are key to mitigating the health risks associated with infected mushrooms.

Can Mushrooms Hear? Exploring Fungi's Sensory Abilities and Communication

You may want to see also

Testing Mushrooms for H. Pylori

Observation: While *Helicobacter pylori* (H. pylori) is primarily associated with human gastric infections, its presence in environmental sources, including food, raises questions about contamination pathways. Mushrooms, being porous and grown in soil, could theoretically harbor bacteria, but testing them for H. pylori requires specific protocols to ensure accuracy.

Analytical Approach: Testing mushrooms for H. pylori involves both microbiological and molecular methods. Culturing techniques, such as using selective agar plates like Skirrow’s medium, can isolate the bacterium, but H. pylori’s fastidious growth requirements often necessitate PCR (polymerase chain reaction) for definitive detection. PCR amplifies the bacterium’s DNA, targeting genes like *ureA* or *glmM*, offering sensitivity down to a few bacterial cells per gram of sample. However, false positives can occur due to DNA contamination, so controls are critical.

Instructive Steps: To test mushrooms, begin by homogenizing a 10-gram sample in sterile saline solution. Filter the suspension to remove debris, then inoculate both culture media and PCR tubes. For culture, incubate at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions (5% O₂, 10% CO₂) for 5–7 days. Simultaneously, extract DNA using a kit designed for gram-negative bacteria and run PCR with H. pylori-specific primers. Compare results against positive and negative controls to validate findings.

Cautions: Cross-contamination is a significant risk, especially in PCR-based testing. Use separate workstations for sample preparation and DNA amplification. Additionally, mushrooms’ natural microbiota can inhibit H. pylori growth in culture or interfere with PCR, so dilution or enrichment steps may be necessary. False negatives are also possible if the bacterial load is low, so testing multiple samples increases reliability.

Do Psychedelic Mushrooms Show Up in Standard Drug Tests?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, *Helicobacter pylori* (H. pylori) is a bacterium that primarily infects the stomach lining of humans and is not naturally found in mushrooms or other plants.

No, mushrooms are not a source of H. pylori infection. H. pylori is typically transmitted through contaminated food, water, or close person-to-person contact, not through mushrooms.

No, consuming mushrooms does not cause H. pylori infection. The bacterium is not present in mushrooms, and proper food hygiene practices can further reduce any risk of contamination.