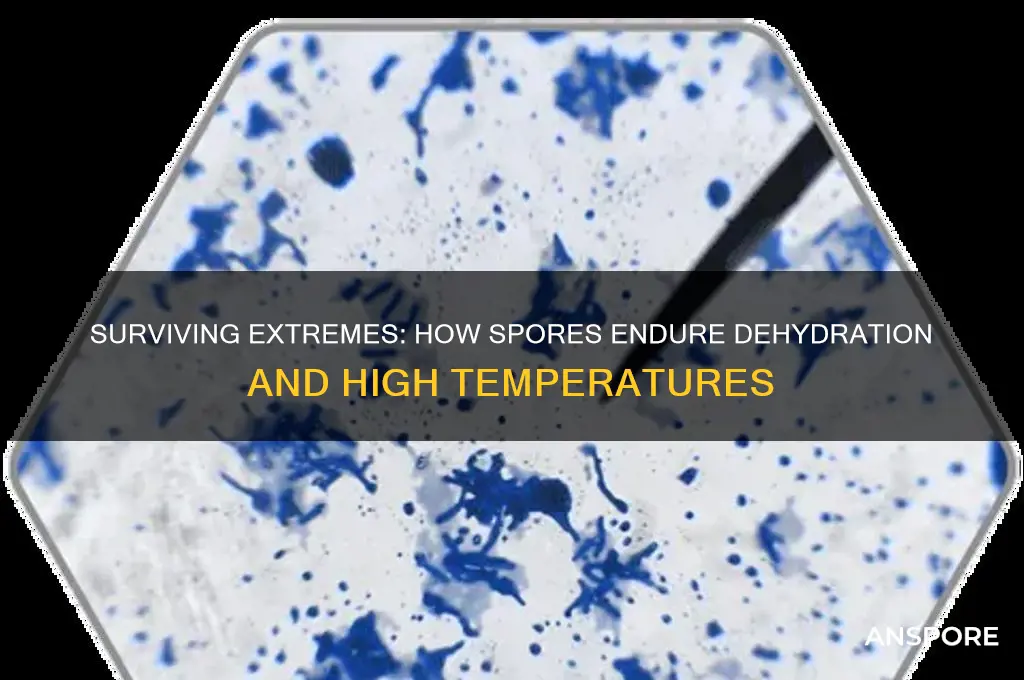

Spores, the highly resilient reproductive structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme environmental conditions. One of the most remarkable aspects of their survival capabilities is their resistance to dehydration and high temperatures, which are often lethal to other forms of life. When exposed to arid conditions, spores can enter a state of dormancy, minimizing metabolic activity and reducing water loss, allowing them to endure prolonged periods of desiccation. Similarly, their robust cell walls and protective coatings enable them to tolerate elevated temperatures that would denature proteins and disrupt cellular functions in most organisms. This extraordinary adaptability makes spores a subject of significant interest in fields such as astrobiology, food preservation, and biotechnology, as understanding their survival mechanisms could provide insights into life's persistence in harsh environments and inspire new technologies for preserving biological materials.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival in Dehydration | Spores can survive extreme desiccation for extended periods, often years or even decades. This is due to their low water content and robust cell wall structure. |

| Survival in High Temperatures | Many spores are highly heat-resistant and can survive temperatures above 100°C. Some bacterial spores (e.g., Bacillus and Clostridium) can withstand temperatures up to 120°C or higher. |

| Mechanism of Heat Resistance | Heat resistance is attributed to the presence of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and a thick protein coat (e.g., small acid-soluble proteins, SASPs) that protect the spore's DNA and core. |

| Rehydration and Germination | Spores can rapidly rehydrate and germinate when favorable conditions (e.g., water, nutrients, and appropriate temperature) return, allowing them to resume metabolic activity. |

| Applications in Industry | Their resistance to dehydration and heat makes spores useful in food preservation, sterilization processes, and as biological indicators for autoclave efficiency. |

| Environmental Persistence | Spores can persist in soil, water, and other environments for long periods, contributing to their role as potential pathogens or contaminants in various settings. |

| Limitations | While highly resistant, spores are not invincible. Prolonged exposure to extreme conditions (e.g., very high temperatures or harsh chemicals) can eventually kill them. |

| Examples of Spore-Forming Organisms | Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), Clostridium botulinum (causes botulism), and Aspergillus (fungal spores) are well-known examples of organisms that produce heat- and desiccation-resistant spores. |

Explore related products

$10.19 $19.22

What You'll Learn

Mechanisms of spore resistance to dehydration

Spores, particularly those of bacteria and fungi, exhibit remarkable resilience to dehydration, a trait that ensures their survival in harsh environments. This resistance is not merely a passive endurance but an active, multifaceted mechanism honed through evolution. At the core of this survival strategy is the spore’s ability to reduce water content to levels as low as 1-10% of its dry weight, a process that would be lethal to most other life forms. This desiccation tolerance hinges on several key adaptations, each contributing uniquely to the spore’s ability to withstand the absence of water.

One critical mechanism is the accumulation of small, highly soluble molecules known as compatible solutes. These include sugars like trehalose and mannitol, which act as molecular shields, stabilizing cellular structures and preventing the denaturation of proteins and membranes during dehydration. Trehalose, for instance, forms a glass-like matrix around proteins, effectively preserving their native conformations even in the absence of water. This protective effect is so potent that spores can survive decades in a dry state, only to revive upon rehydration. Practical applications of this knowledge are seen in the food industry, where trehalose is used to extend the shelf life of dried products by mimicking the spore’s natural preservation methods.

Another vital adaptation is the spore’s robust cell wall, which undergoes significant modifications during sporulation. This wall is enriched with dipicolinic acid (DPA), a calcium-chelating molecule that binds to water molecules, reducing their availability for chemical reactions that could damage the spore. DPA also contributes to the spore’s heat resistance, a trait often coupled with dehydration tolerance. The cell wall itself is composed of peptidoglycan and additional layers of proteins and polymers, creating a barrier that minimizes water loss and protects against mechanical stress. This structural reinforcement is akin to building a fortress around the spore’s genetic material, ensuring its integrity even under extreme conditions.

Beyond molecular and structural defenses, spores employ metabolic shutdown as a survival tactic. During dehydration, metabolic activity is drastically reduced, minimizing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could otherwise cause oxidative damage. This dormancy is not permanent but a reversible state, allowing spores to “wait out” unfavorable conditions. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can remain viable for centuries, a testament to the effectiveness of this strategy. To replicate this in practical scenarios, such as preserving biological materials, controlled dehydration processes that mimic the spore’s natural dormancy induction can be employed, ensuring long-term viability.

Lastly, the spore’s DNA is protected by specialized proteins that prevent damage from desiccation-induced stress. These proteins, such as DNA-binding proteins from starved cells (Dps), shield DNA from hydroxyl radicals and other harmful byproducts of dehydration. This protection is crucial, as even minor DNA damage could render the spore non-viable upon rehydration. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on spore biology but also inspires biotechnological innovations, such as developing desiccation-tolerant crops or improving the stability of vaccines and enzymes in dry formulations. By studying spores, we unlock principles of survival that transcend microbiology, offering solutions to challenges in agriculture, medicine, and beyond.

Are Spores Always Dispersed? Unraveling Nature's Seed Scattering Secrets

You may want to see also

Heat tolerance in bacterial endospores

Bacterial endospores are nature's ultimate survivalists, capable of withstanding extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. Among their remarkable abilities, heat tolerance stands out as a critical factor in their resilience. Endospores can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C, a feat achieved through a combination of structural and biochemical adaptations. This heat resistance is not merely a passive trait but an active defense mechanism honed over millennia of evolutionary pressure.

Consider the process of autoclaving, a standard sterilization method in laboratories and medical settings, which subjects materials to temperatures of 121°C for 15–20 minutes. While this effectively kills vegetative bacteria, endospores of species like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis* can persist. Their survival hinges on a multi-layered protective coat, low water content, and the presence of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a calcium-chelating molecule that stabilizes the spore’s internal structure. Heat tolerance in endospores is not uniform; some species, such as *Bacillus subtilis*, can withstand higher temperatures than others, making them ideal subjects for studying extremophile biology.

To neutralize endospores, prolonged exposure to high temperatures is necessary. For instance, moist heat at 121°C requires at least 15 minutes to achieve sterilization, while dry heat at 160°C may take up to 2 hours. This disparity underscores the importance of moisture in heat inactivation, as water acts as a conductor of heat, accelerating the denaturation of spore proteins. Practical applications of this knowledge are seen in food preservation techniques like canning, where temperatures of 116°C–121°C are maintained for 10–20 minutes to ensure safety.

The heat tolerance of endospores also poses challenges in healthcare and industrial settings. For example, improper sterilization of medical equipment can lead to infections caused by spore-forming pathogens. To mitigate this risk, protocols must account for the specific heat resistance of target species. In research, understanding spore heat tolerance aids in developing more effective decontamination methods, such as combining heat with chemical agents or radiation.

In conclusion, the heat tolerance of bacterial endospores is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By studying their mechanisms of resistance, we not only gain insights into microbial survival strategies but also develop better tools to combat them. Whether in food safety, medicine, or environmental science, this knowledge is indispensable for ensuring sterility and preventing contamination.

Reishi Spore Triterpenes: Unveiling Their Bitter Taste and Benefits

You may want to see also

Fungal spore survival in extreme conditions

Fungal spores are remarkably resilient, capable of withstanding conditions that would destroy most other forms of life. Dehydration and high temperatures, in particular, pose significant challenges, yet many fungal species have evolved mechanisms to endure these extremes. For instance, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* spores can survive desiccation for years, maintaining viability until rehydration occurs. Similarly, *Trichoderma* spores tolerate temperatures exceeding 60°C, a trait exploited in industrial processes like composting. This survival is attributed to their robust cell walls, composed of chitin and glucans, which provide structural integrity and protect against environmental stressors. Additionally, spores often accumulate protective molecules like trehalose, a sugar that stabilizes cellular structures during dehydration.

To understand how fungal spores survive such conditions, consider their dormancy strategies. When faced with dehydration, spores enter a metabolically inactive state, minimizing water loss and halting biochemical reactions that require hydration. This quiescent phase allows them to persist in arid environments, such as deserts or high-altitude regions. High temperatures, on the other hand, are countered through heat shock proteins, which prevent protein denaturation and maintain cellular function. For example, *Neurospora crassa* spores produce HSP70 proteins in response to heat stress, ensuring survival at temperatures up to 50°C. These adaptive mechanisms highlight the evolutionary sophistication of fungal spores, enabling them to thrive in niches inaccessible to most organisms.

Practical applications of fungal spore resilience are widespread, particularly in agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers use *Trichoderma* spores as biofungicides, applying them to soil even in hot climates where temperatures exceed 40°C. These spores remain viable, colonizing plant roots and protecting against pathogens like *Fusarium*. Similarly, in food preservation, fungal spores’ tolerance to dehydration and heat is both a challenge and an opportunity. While they can contaminate dried goods, their resilience also inspires the development of preservation techniques, such as using spore-derived enzymes to stabilize foods under extreme conditions. Understanding these survival strategies allows industries to harness fungal spores’ strengths while mitigating their drawbacks.

Despite their toughness, fungal spores are not invincible. Prolonged exposure to temperatures above 70°C or extreme pH levels can compromise their viability. For instance, *Aspergillus niger* spores, though heat-tolerant, are inactivated after 10 minutes at 80°C. This knowledge is crucial for sterilization protocols in medical and food industries, where complete spore eradication is essential. Additionally, combining dehydration with other stressors, such as UV radiation or chemical agents, can enhance spore inactivation. For example, treating *Cladosporium* spores with hydrogen peroxide (3% solution) under dry conditions reduces their survival rate by 90%. Such targeted approaches underscore the importance of understanding spore vulnerabilities alongside their strengths.

In conclusion, fungal spore survival in extreme conditions is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Their ability to withstand dehydration and high temperatures stems from a combination of structural defenses, metabolic adaptations, and protective molecules. While this resilience poses challenges in certain contexts, it also offers opportunities for innovation in agriculture, biotechnology, and preservation. By studying these mechanisms, we can develop strategies to both exploit and counteract fungal spores’ remarkable durability, ensuring their benefits are maximized while their risks are minimized. Whether in the lab or the field, this knowledge is indispensable for navigating the complex interplay between fungi and their environments.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Pink Eye? Uncovering the Surprising Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spore coat in protection

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, owe their ability to withstand extreme conditions like dehydration and high temperatures largely to their spore coats. This multi-layered protective shell acts as a biological fortress, safeguarding the spore's genetic material and metabolic machinery from environmental assaults.

Comprising proteins, peptides, and complex carbohydrates, the spore coat's composition varies across species, reflecting adaptations to specific ecological niches. For instance, the spore coat of *Bacillus subtilis*, a common soil bacterium, contains keratin-like proteins that provide rigidity and resistance to desiccation.

Imagine the spore coat as a meticulously engineered suit of armor, each layer serving a distinct purpose. The outermost layer, often rich in hydrophobic proteins, repels water, preventing desiccation and maintaining internal hydration. Beneath this lies a layer with cross-linked proteins, creating a robust mesh that resists mechanical stress and enzymatic degradation. Some spore coats even incorporate pigments that absorb harmful UV radiation, further enhancing survival in harsh environments. This multi-layered defense system allows spores to endure conditions that would be lethal to most other life forms.

In the context of high temperatures, the spore coat plays a crucial role in preventing protein denaturation and DNA damage. Certain spore coat proteins act as molecular chaperones, stabilizing the spore's internal proteins and preventing them from unfolding under heat stress. Additionally, the coat's structure may limit the diffusion of heat, slowing down the rate of internal temperature rise and providing the spore with precious time to activate repair mechanisms.

Understanding the intricate architecture and functionality of the spore coat has significant implications. For example, in the food industry, knowledge of spore coat resistance mechanisms can inform the development of more effective sterilization techniques. By targeting specific vulnerabilities in the coat, such as its sensitivity to certain enzymes or chemicals, we can design treatments that ensure complete spore inactivation, enhancing food safety. Conversely, in biotechnology, harnessing the protective properties of spore coats could lead to the development of novel biomaterials for preserving sensitive biological agents or creating durable drug delivery systems.

Are Spore Syringes Legal in California? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Impact of temperature on spore viability

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme conditions. However, their tolerance to high temperatures is not universal. While some spores can endure temperatures exceeding 100°C, others are inactivated at much lower thresholds. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a process routinely used in laboratories to sterilize equipment. In contrast, spores of *Aspergillus* fungi may lose viability at temperatures above 70°C for prolonged periods. This variability underscores the importance of understanding species-specific responses to heat when assessing spore survival.

The impact of temperature on spore viability is not solely determined by the maximum heat exposure but also by the duration and rate of heating. A rapid increase in temperature, such as flash pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds, may not fully inactivate all spores, whereas slower heating processes at lower temperatures can be more effective. This phenomenon is attributed to the differential activation of heat-shock proteins and DNA repair mechanisms within the spore. For example, in the food industry, canned goods are heated to 116°C for 30 minutes to ensure the destruction of *Clostridium botulinum* spores, a critical step in preventing foodborne illness.

Practical applications of temperature control in spore management extend beyond sterilization. In agriculture, soil solarization—a technique involving covering moist soil with clear plastic to raise temperatures to 50–60°C—is used to reduce weed seeds and soilborne pathogens. While this method is effective against many spores, it may not eliminate heat-resistant species like *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*. Similarly, in healthcare, medical instruments are exposed to temperatures of 134°C for 3 minutes in steam sterilizers to ensure the destruction of all microbial spores, a standard protocol in infection control.

To optimize temperature-based spore inactivation, consider the following steps: first, identify the target spore species and its known heat tolerance. Second, select a heating method (dry heat, moist heat, or steam) that aligns with the spore’s resistance mechanisms. Third, monitor both temperature and exposure time meticulously, as deviations can compromise efficacy. For example, in water purification, temperatures above 70°C for 10 minutes are recommended to inactivate most waterborne spores, but this may vary depending on local microbial flora.

Despite their remarkable resilience, spores are not invincible to heat. By leveraging temperature-specific vulnerabilities, industries from food processing to healthcare can effectively manage spore-related risks. However, caution must be exercised, as over-reliance on heat without considering spore type or heating dynamics can lead to incomplete inactivation. Ultimately, a nuanced understanding of temperature’s impact on spore viability is essential for designing robust sterilization and control strategies.

Are Spore Syringes Illegal? Understanding Legal Boundaries and Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are highly resistant to dehydration due to their thick cell walls and low water content, allowing them to remain dormant and viable for extended periods.

Yes, many spores can withstand high temperatures, including those from boiling water or even sterilization processes, thanks to their heat-resistant structures like the spore coat.

Spores can survive in dehydrated conditions for years, decades, or even centuries, depending on the species and environmental factors like humidity and temperature.

No, resistance varies among species. For example, bacterial endospores are more resistant than fungal spores, and some spores have evolved to tolerate extreme conditions better than others.