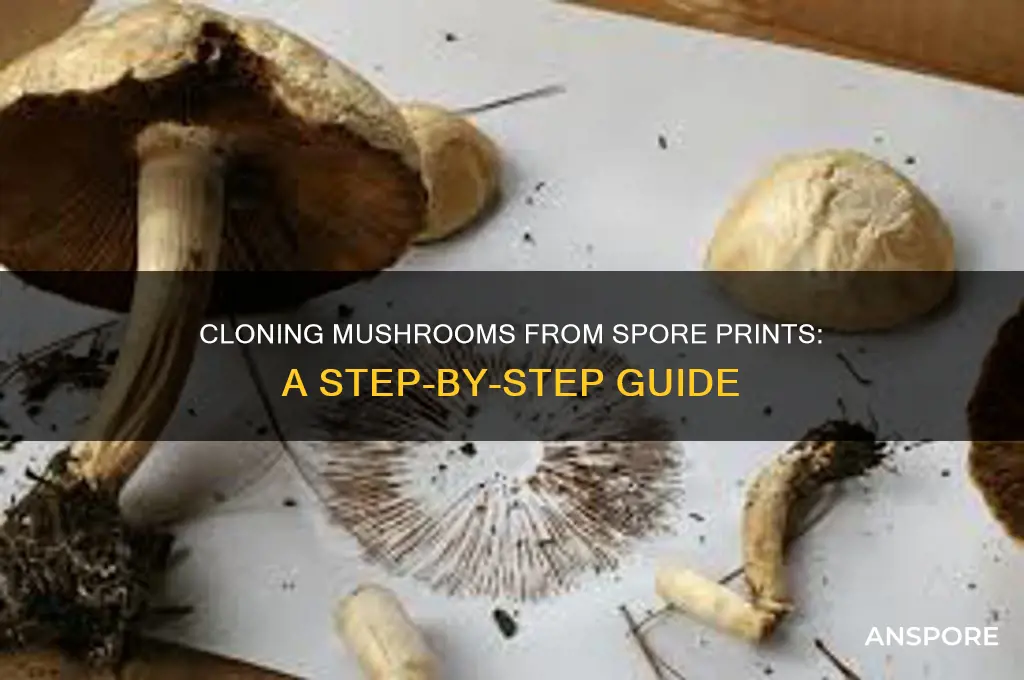

Cloning mushrooms from a spore print is a fascinating process that allows cultivators to replicate specific mushroom strains with desirable traits. A spore print, which is a collection of spores released by a mature mushroom cap, serves as the starting point for this method. By carefully collecting and cultivating these spores under controlled conditions, mycologists can initiate the growth of mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. This mycelium can then be transferred to a suitable substrate, where it will eventually produce new mushrooms genetically identical to the parent. While the process requires precision and sterile techniques to avoid contamination, it offers a reliable way to preserve and propagate unique mushroom varieties, making it a valuable technique in both scientific research and gourmet mushroom cultivation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cloning Method | Spore Print |

| Feasibility | Yes, but challenging |

| Success Rate | Variable (depends on technique, species, and conditions) |

| Required Materials | Spore print, sterile agar plates, scalpel, sterile syringe, growth chamber |

| Process Steps | 1. Collect spore print 2. Sterilize equipment 3. Transfer spores to agar 4. Incubate for mycelium growth 5. Transfer mycelium to substrate |

| Time Frame | Several weeks to months |

| Species Suitability | Varies; some species are easier to clone than others |

| Contamination Risk | High (requires strict sterile technique) |

| Advantages | Preserves genetic diversity, allows for cultivation of specific strains |

| Disadvantages | Time-consuming, requires precision, lower success rate compared to tissue culture |

| Alternative Methods | Tissue culture, grain spawn, liquid culture |

| Common Challenges | Contamination, slow growth, genetic variability among spores |

| Recommended for | Experienced cultivators, research purposes, preserving rare species |

Explore related products

$12.74 $14.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Print Collection: Gather spores by placing mushroom cap on paper for several hours

- Sterilization Techniques: Clean tools and surfaces to prevent contamination during cloning process

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare nutrient-rich medium like agar or grain for spore germination

- Inoculation Process: Transfer spores to substrate using sterile techniques to start growth

- Incubation Conditions: Maintain optimal temperature, humidity, and light for successful mushroom cloning

Spore Print Collection: Gather spores by placing mushroom cap on paper for several hours

Spore print collection is a straightforward yet fascinating process that allows you to gather spores from a mushroom cap for cultivation or study. By placing the cap gill-side down on a piece of paper, you create an environment where spores naturally drop over several hours. This method is not only simple but also highly effective, making it a favorite among mycologists and hobbyists alike. The key lies in patience and precision: ensure the cap is fully mature for optimal spore release, and choose a clean, dry surface to avoid contamination.

To begin, select a healthy, fully opened mushroom with visible gills. Gently twist or cut the stem to separate the cap, taking care not to damage the delicate gill structure. Place the cap gill-side down on a piece of white or black paper—the contrast helps visualize the spore deposit. Cover the setup with a glass or bowl to maintain humidity and prevent air currents from dispersing the spores. Leave it undisturbed for 6–12 hours, depending on the species and environmental conditions. For example, *Psylocybe* spores may drop within 4 hours, while *Oyster* mushrooms might take closer to 8.

While spore print collection is relatively foolproof, there are nuances to consider. Humidity is critical; if the air is too dry, spores may not release effectively. Conversely, excessive moisture can lead to mold growth. Temperature also plays a role—most mushrooms prefer a range of 68–75°F (20–24°C) for optimal spore release. Additionally, avoid handling the cap with bare hands to prevent oils or contaminants from interfering with the process. Using gloves or tweezers can help maintain sterility.

Once the spores have dropped, carefully lift the cap to reveal a distinct pattern—your spore print. This can be used for identification, art, or cultivation. For cloning, however, spores are just the beginning. They must be sterilized and introduced to a nutrient-rich substrate to grow mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. While spore prints are a vital step, they are not a direct clone of the parent mushroom; rather, they carry genetic diversity, potentially producing variations in subsequent generations.

In conclusion, spore print collection is a blend of art and science, offering both practical and educational value. It’s a gateway to understanding fungal reproduction and a foundational skill for mushroom cultivation. With minimal equipment and a bit of patience, anyone can master this technique, unlocking the world of mycology one spore at a time.

Can Toddlers Safely Eat Mushrooms? A Parent's Guide to Nutrition

You may want to see also

Sterilization Techniques: Clean tools and surfaces to prevent contamination during cloning process

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of mushroom cloning, capable of derailing weeks of effort in a matter of days. Even a single stray bacterium or mold spore can outcompete your delicate mycelium, turning your sterile substrate into a microbial battleground. This makes sterilization not just a step, but the foundation of successful cloning.

Every surface, tool, and even your hands become potential vectors for contamination. A spore print, while containing the genetic blueprint for your mushroom, is also a haven for microorganisms. Without meticulous sterilization, you're essentially inviting competitors to the party.

The Sterilization Arsenal:

Think of sterilization as a multi-pronged attack. Heat is your heavy artillery. Autoclaving, a process using pressurized steam at 121°C (250°F) for 15-30 minutes, is the gold standard for sterilizing substrates, jars, and tools. For heat-sensitive items like petri dishes or agar, flame sterilization with a bunsen burner or alcohol lamp provides a quick, intense blast. Chemical disinfectants like 70% isopropyl alcohol or 10% bleach solution are useful for wiping down surfaces and tools, but remember, they don't penetrate deeply and require thorough drying to avoid harming your mycelium.

Beyond the Tools: Creating a Clean Zone

Your workspace itself demands attention. Designate a specific area for cloning, ideally with good ventilation and minimal foot traffic. HEPA filters can be a game-changer, removing airborne contaminants. Cover your hair with a cap or net, and wear sterile gloves to minimize shedding skin cells and hair follicles, both potential contamination sources. Remember, even the cleanest environment can be compromised by a sneeze or a gust of wind, so work with deliberate, controlled movements.

Pro Tip: Create a "sterile flow" by arranging your workspace in a way that minimizes backtracking and potential cross-contamination.

The Devil's in the Details:

Don't underestimate the power of seemingly insignificant details. Label everything clearly to avoid confusion and accidental contamination. Date your sterilized materials and discard anything past its prime. Inspect your tools regularly for cracks or damage that could harbor contaminants. Even the smallest oversight can lead to disaster. Think of sterilization as a meticulous dance, where every step, every surface, and every tool plays a crucial role in the delicate ballet of mushroom cloning.

Can Shiitake Mushrooms Thrive on Maple Trees? A Guide

You may want to see also

Substrate Preparation: Prepare nutrient-rich medium like agar or grain for spore germination

Cloning mushrooms from a spore print begins with a critical step: preparing a nutrient-rich substrate that encourages spore germination. Unlike wild environments where spores land on unpredictable surfaces, controlled cultivation requires a tailored medium like agar or grain. These substrates provide the essential nutrients, moisture, and structure spores need to develop into mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus.

Analytical Perspective: Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, is a popular choice for initial spore germination due to its sterile nature and ability to support rapid mycelial growth. Grain substrates, such as rye or millet, offer a more nutrient-dense environment but require sterilization to prevent contamination. The choice between agar and grain depends on the cultivator’s goals: agar is ideal for isolating pure cultures, while grain is better for bulk mycelium production. Both substrates must be properly hydrated and sterilized to ensure spores have a clean, nutrient-rich foundation.

Instructive Steps: To prepare agar, mix 20 grams of agar powder with 1 liter of distilled water, then add 1 liter of nutrient solution (e.g., light malt extract or potato dextrose). Heat the mixture until the agar dissolves, pour it into sterile Petri dishes, and allow it to cool. For grain substrates, soak 1 kilogram of rye berries in water for 12–24 hours, drain, and steam for 1–2 hours to cook and sterilize. Let the grain cool before inoculating with spores. Always work in a sterile environment to avoid contamination, using tools like a pressure cooker for sterilization and a laminar flow hood for inoculation.

Comparative Insight: While agar provides a clear, sterile surface to observe mycelial growth and isolate specific strains, grain substrates mimic natural conditions more closely, promoting robust mycelial development. Agar is more forgiving for beginners due to its simplicity and visibility, but grain substrates are cost-effective for larger-scale cultivation. Both require precision in preparation: agar must be free of impurities, and grain must be properly hydrated and sterilized to prevent mold or bacterial growth.

Practical Tips: Maintain a pH level between 5.5 and 6.5 for optimal spore germination. Label all substrates with preparation dates to track freshness. Store prepared agar plates at 4°C (39°F) for up to 2 weeks, and grain substrates in sealed containers in a cool, dark place. When inoculating, use a spore syringe or print to evenly distribute spores across the substrate. Patience is key—spore germination can take 7–21 days, depending on the mushroom species and environmental conditions.

Old Man of the Woods Mushroom: Identifying Look-Alikes and Avoiding Confusion

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99

Inoculation Process: Transfer spores to substrate using sterile techniques to start growth

Spores are the microscopic seeds of the fungal world, and transferring them to a nutrient-rich substrate is the first step in cultivating mushrooms. This process, known as inoculation, requires precision and sterility to ensure successful colonization. Imagine a surgeon in an operating room—every movement deliberate, every tool sanitized—because contamination can derail the entire endeavor. The substrate, often a mixture of grains or sawdust, must be prepared and sterilized to eliminate competing organisms. Once cooled, it becomes a blank canvas ready to receive the spores, which are typically suspended in a sterile solution or carefully scattered using a sterile tool.

The inoculation process begins with a spore print, a delicate deposit of spores collected from a mature mushroom cap. To transfer these spores, a sterile syringe or scalpel is used to scrape a small amount of the print. This material is then introduced to the substrate in a controlled environment, such as a still air box or laminar flow hood, to minimize airborne contaminants. For liquid cultures, spores are mixed into a sterile nutrient broth, which is later used to inoculate the substrate. Timing is critical: too much handling or exposure to air increases the risk of contamination. Think of it as planting a garden in a vacuum—every step must be calculated to protect the fragile ecosystem you’re creating.

Sterile technique is non-negotiable in this process. Autoclaving substrates at 121°C (250°F) for 30–60 minutes ensures all competing microbes are eradicated. Hands, tools, and work surfaces must be disinfected with 70% isopropyl alcohol or a similar agent. Even the air can be a threat, so working during calm, low-humidity periods or using a HEPA filter can reduce airborne spores. Beginners often underestimate the importance of cleanliness, only to find their substrate overrun with mold. It’s a lesson learned quickly: in mushroom cultivation, sterility is survival.

Once inoculated, the substrate is sealed in a grow bag or jar and placed in a dark, temperature-controlled environment (typically 70–75°F or 21–24°C) to encourage mycelial growth. This phase, known as incubation, can take weeks, during which the mycelium colonizes the substrate. Patience is key—rushing or disturbing the container can introduce contaminants or stress the mycelium. Monitoring for signs of mold or slow growth is essential, as early intervention can salvage a batch. Successful inoculation sets the stage for fruiting, where the real magic happens, but it all begins with this meticulous, sterile transfer of spores to substrate.

Mushrooms for Weight Loss: Unlocking Nature's Slimming Superfood Potential

You may want to see also

Incubation Conditions: Maintain optimal temperature, humidity, and light for successful mushroom cloning

Mushroom cloning from a spore print is a delicate process that hinges on precise incubation conditions. Temperature, humidity, and light are the trifecta of factors that can make or break your cloning endeavor. Each species has its own preferences, but a general rule of thumb is to maintain a temperature range of 70-75°F (21-24°C) during incubation. This range mimics the natural environment of many mushroom species, promoting healthy mycelium growth.

Consider the humidity levels, which should be kept consistently high, around 90-95%. This can be achieved by using a humidifier or placing a tray of water near the incubation chamber. However, be cautious not to oversaturate the environment, as excessive moisture can lead to contamination. A simple yet effective method is to use a clear plastic container with a lid, creating a mini-greenhouse effect. Mist the inside of the container with water, and ensure proper air circulation by poking small holes in the lid.

Light requirements for mushroom cloning are often overlooked, but they play a crucial role in the process. While mushrooms do not require intense light, a gentle, indirect light source can stimulate growth. A fluorescent or LED light placed a few feet away from the incubation chamber is sufficient. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can dry out the substrate and hinder mycelium development. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) thrive in low-light conditions, whereas shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) prefer a slightly brighter environment.

To optimize your cloning setup, consider the following steps: prepare a sterile substrate, such as agar or grain spawn, and inoculate it with the spore print. Place the inoculated substrate in the incubation chamber, maintaining the desired temperature and humidity levels. Monitor the growth regularly, looking for signs of contamination or abnormal development. If using a grain spawn, ensure it is fully colonized before transferring it to a bulk substrate for fruiting. This process may take several weeks, depending on the mushroom species and environmental conditions.

In comparison to traditional mushroom cultivation, cloning from a spore print requires more attention to detail and precision. The success rate can be significantly improved by maintaining optimal incubation conditions. For example, a study on shiitake mushroom cloning found that a temperature of 73°F (23°C) and 95% humidity resulted in a 90% success rate, compared to 60% at suboptimal conditions. By providing the ideal environment, you can increase the likelihood of successful mushroom cloning and ultimately enjoy a bountiful harvest. Remember, patience and attention to detail are key when navigating the intricate world of mushroom cultivation.

Do Mushrooms Have Eternal Life? Exploring Their Remarkable Longevity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, you cannot clone a mushroom directly from a spore print. Spores are haploid cells that, when germinated, produce mycelium through random genetic recombination, resulting in unique offspring rather than an exact clone of the parent mushroom.

A spore print is used for identification, preservation, and propagation of mushroom species. While it doesn’t produce clones, it allows for the cultivation of mushrooms by growing mycelium from spores, which can then be used to produce fruiting bodies.

To clone a mushroom, you must use tissue culture or mycelium from the parent mushroom. Techniques like taking a slice of the mushroom’s cap or stem and growing it on a sterile medium can produce an exact genetic copy of the parent.

No, spores from a spore print will produce genetically diverse offspring due to sexual reproduction. To ensure specific traits are preserved, cloning methods using mycelium or tissue from the parent mushroom are necessary.