Eating slimy mushrooms is a topic that raises both curiosity and caution. While some mushrooms develop a slimy texture due to moisture or age, not all slimy mushrooms are unsafe to consume. Certain edible varieties, like oyster mushrooms, naturally have a slightly slippery surface when fresh, which is harmless. However, sliminess can also indicate spoilage, bacterial growth, or the presence of toxic species. It’s crucial to identify the mushroom accurately and assess its condition before consumption. When in doubt, it’s best to avoid slimy mushrooms, as misidentification or consuming spoiled ones can lead to illness. Always prioritize safety and consult a reliable guide or expert if unsure.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Depends on the species; some slimy mushrooms are edible, while others are toxic or inedible. |

| Common Edible Species | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), Enoki mushrooms (Flammulina velutipes), and some species of Agaricus. |

| Common Toxic Species | Certain species of Amanita, such as the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), and some species of Cortinarius. |

| Sliminess Cause | Natural moisture, decomposition, or bacterial growth; not always an indicator of spoilage. |

| Safe Consumption | Sliminess alone is not a definitive sign of toxicity; proper identification and freshness are crucial. |

| Preparation Tips | Clean slimy mushrooms gently, cook thoroughly, and avoid consuming if unsure about the species. |

| Health Risks | Misidentification can lead to poisoning, allergic reactions, or gastrointestinal issues. |

| Expert Advice | Consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide for accurate identification before consumption. |

Explore related products

$9.99

What You'll Learn

Identifying Safe Slime Types

Slime on mushrooms can be a red flag, but not all slimy mushrooms are toxic. Understanding the type of slime and its source is crucial for determining edibility. For instance, the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) often has a slightly slimy cap when young, which is perfectly safe to eat. This slime is a natural part of its moisture content and does not indicate spoilage or toxicity. Conversely, slime caused by bacterial growth or decay, often seen as a thick, off-color layer, is a clear sign to discard the mushroom. The key is to differentiate between natural, species-specific slime and slime resulting from deterioration or contamination.

To identify safe slime types, start by examining the mushroom’s species. Some mushrooms, like the Shaggy Mane (*Coprinus comatus*), naturally exude a black, inky slime as they mature, which is harmless but signals the mushroom is past its prime for consumption. Others, such as the Enoki Mushroom (*Flammulina velutipes*), may have a slight natural sheen or moisture that is safe to eat. Always cross-reference with reliable field guides or apps like iNaturalist to confirm the species. If the slime appears unnatural—thick, discolored, or accompanied by a foul odor—it’s a warning sign, regardless of the mushroom type.

A practical tip for assessing slime is the touch test. Gently press the mushroom’s surface; if the slime feels like a thin, water-like film and the mushroom itself is firm, it’s likely safe. However, if the slime is sticky, stringy, or the mushroom feels soft and mushy, it’s best discarded. Additionally, consider the environment where the mushroom was found. Mushrooms growing in damp, contaminated areas are more prone to harmful slime-causing bacteria. Always clean wild mushrooms thoroughly before inspection, as dirt or debris can mimic slime.

For foragers and cooks, understanding the lifecycle of mushrooms is essential. Young mushrooms often have a natural sheen or moisture that dissipates as they mature. For example, Chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*) may have a slightly glossy cap when young, which is safe. However, as mushrooms age, natural enzymes break down their tissues, leading to a slimy texture that indicates spoilage. A rule of thumb: if the slime is part of the mushroom’s natural appearance and the mushroom is otherwise healthy, it’s likely edible. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and consult an expert.

Finally, while some slime is safe, it’s often a matter of preference. Many cooks prefer to remove the slimy layer from mushrooms like Nameko (*Pholiota nameko*), which has a naturally gelatinous coating, before cooking. This can be done by gently wiping the caps with a damp cloth or blanching them briefly. Remember, safe slime is species-specific and should never be assumed without proper identification. By combining knowledge of mushroom biology, sensory tests, and environmental context, you can confidently distinguish between edible and unsafe slimy mushrooms.

Can You Eat Morel Mushrooms Raw? Risks and Safe Preparation Tips

You may want to see also

Risks of Eating Slimy Mushrooms

Slime on mushrooms often signals bacterial growth, a natural decomposition process that can turn a once-edible fungus into a potential health hazard. This bacterial activity thrives in moist environments, breaking down the mushroom’s structure and releasing byproducts that may cause foodborne illnesses. While not all slimy mushrooms are toxic, the slime itself indicates a higher risk of contamination, making consumption a gamble with your digestive system.

Consider the scenario: a forgotten container of mushrooms in the fridge, now coated in a translucent film. Eating these without thorough inspection could expose you to pathogens like *Salmonella* or *E. coli*, which flourish in such conditions. Symptoms of bacterial contamination include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, typically appearing within 6 to 24 hours. For individuals with compromised immune systems, children under five, or adults over 65, these symptoms can escalate to severe dehydration or systemic infections, requiring medical attention.

The texture of slime also hints at enzymatic breakdown, where mushrooms release digestive enzymes to recycle nutrients. While this process isn’t inherently harmful, it alters the mushroom’s flavor and nutritional profile, often making it unpalatable. Cooking slimy mushrooms might kill surface bacteria, but it won’t reverse the enzymatic changes that have already occurred. As a rule, if a mushroom feels excessively slippery or emits a sour odor, discard it—no recipe or cooking method can salvage its safety or taste.

To minimize risks, store mushrooms properly: keep them unwashed in a paper bag in the refrigerator, where they’ll stay fresh for up to a week. If slime appears, inspect the batch carefully; isolated spots might be removable, but widespread slime warrants disposal. When in doubt, err on the side of caution—the cost of wasting mushrooms pales compared to the potential health consequences. Remember, slime is nature’s warning sign, and ignoring it could turn a meal into a medical issue.

Can Mushrooms Thrive Anywhere? Exploring Their Adaptability to Diverse Environments

You may want to see also

Proper Cleaning Techniques

Slime on mushrooms often indicates excess moisture, which can accelerate spoilage and harbor bacteria. Proper cleaning techniques are essential to salvage slimy mushrooms safely, but not all cases warrant rescue. If the slime is thick, discolored, or accompanied by a foul odor, discard the mushrooms immediately—these are signs of advanced decay. For mildly slimy mushrooms, however, a thorough cleaning can restore their usability, though texture and flavor may be compromised.

Begin by gently brushing off loose slime and debris with a soft-bristled mushroom brush or a clean paper towel. Avoid rinsing under water at this stage, as excess moisture exacerbates slime. Next, trim any visibly affected areas with a sharp knife, removing the slimy portions entirely. For stubborn slime, a damp cloth can be used to wipe the surface, but pat dry immediately to prevent water absorption. This method minimizes moisture while addressing the slime effectively.

After initial cleaning, submerge the mushrooms in a bowl of cold water mixed with 1 tablespoon of white vinegar per cup of water. Vinegar’s acidity helps dissolve remaining slime and kills surface bacteria. Let them soak for 2–3 minutes, then gently agitate the water to dislodge particles. Rinse thoroughly under running water and pat dry with paper towels or a clean kitchen cloth. This two-step process ensures cleanliness without oversaturating the mushrooms.

Caution: Over-cleaning can damage delicate mushroom textures. Avoid scrubbing aggressively or soaking for extended periods. If slime persists after cleaning, it’s safer to discard the mushrooms. Proper storage prevents future slime—keep mushrooms in paper bags or loosely wrapped in paper towels in the refrigerator, allowing airflow while absorbing excess moisture. Cleaned mushrooms should be cooked immediately or stored for no more than 24 hours to prevent recurrence.

In summary, proper cleaning techniques for slimy mushrooms involve a balance of gentle mechanical removal, targeted soaking, and minimal moisture exposure. While mildly slimy mushrooms can be salvaged, prioritize food safety and discard those showing advanced spoilage. Cleaned mushrooms are best used in cooked dishes, where texture differences are less noticeable. Always store mushrooms correctly to avoid slime in the first place, ensuring freshness and safety.

Can Mushroom NPCs Spawn in Artificial Mushroom Biomes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common Edible Slimy Varieties

Slime on mushrooms often triggers hesitation, but several varieties are not only safe to eat but also prized for their texture and flavor. The Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), for instance, is a prime example. Its naturally slimy cap, particularly when young, is a sign of freshness, not spoilage. This slime, composed of water and polysaccharides, enhances its velvety mouthfeel when cooked. Sautéing or grilling Oyster mushrooms at 350°F (175°C) for 5–7 minutes reduces the slime while retaining their umami richness, making them a versatile addition to stir-fries or soups.

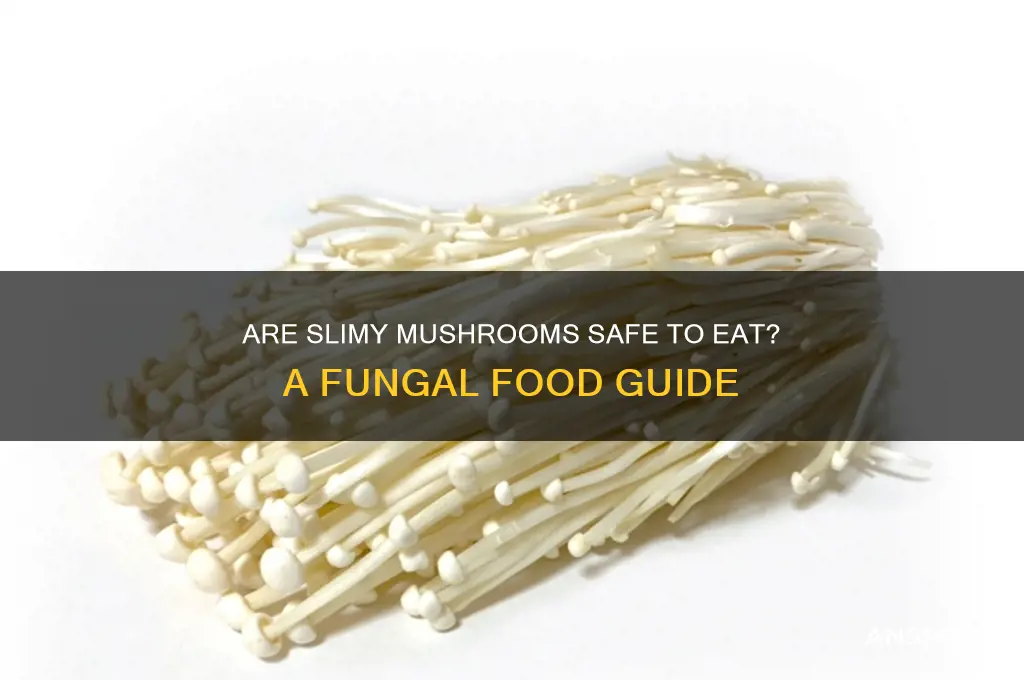

Contrastingly, the Enoki Mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) presents a different slimy profile. Its long, slender stems are coated in a delicate, almost gelatinous layer that becomes pleasantly crunchy when cooked. Unlike Oyster mushrooms, Enoki’s slime is less water-soluble, so quick blanching in boiling water for 30 seconds before stir-frying preserves its texture without making it mushy. This variety is particularly popular in Asian cuisines, where its mild flavor complements broths and salads.

Foraging enthusiasts often encounter the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), a slimy mushroom with a fruity aroma and chewy texture. Its golden, wavy caps are covered in a fine, sticky film that intensifies its flavor when sautéed in butter. However, caution is key: Chanterelles have toxic look-alikes like the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, which lacks their apricot scent. Always perform a spore print test or consult a field guide before consumption.

Lastly, the Nameko (Pholiota nameko) is a Japanese favorite known for its viscous, slippery exterior. This slime, rich in glucan, thickens soups and hot pots, giving them a silky consistency. Unlike other slimy varieties, Nameko’s slime is heat-stable, so prolonged simmering in dishes like miso soup enhances its natural gelatinous quality. Its nutty flavor pairs well with tofu and seaweed, making it a staple in winter comfort foods.

Incorporating these slimy mushrooms into your diet requires understanding their unique properties. While Oyster and Enoki thrive with quick, high-heat cooking, Chanterelles and Nameko benefit from slower methods. Always source mushrooms from reputable suppliers or forage with expert guidance to avoid toxic varieties. With proper preparation, these slimy varieties transform from off-putting to exquisite, offering textures and flavors that elevate any dish.

Where to Buy Philanemo Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Guide for Gamers

You may want to see also

Signs of Spoilage to Avoid

Slime on mushrooms often signals bacterial growth, a red flag for spoilage. This slippery layer forms as microorganisms break down the mushroom’s structure, releasing enzymes that degrade its cell walls. While not all slimy mushrooms are toxic, the slime itself indicates a loss of freshness and potential contamination. If the slime is accompanied by a sour smell or visible mold, discard the mushrooms immediately. Consuming spoiled mushrooms can lead to foodborne illnesses, such as gastrointestinal distress, so err on the side of caution.

Color changes are another critical sign of spoilage. Fresh mushrooms typically have a uniform, vibrant hue. As they deteriorate, they may develop dark spots or turn grayish-brown. These discolorations often coincide with a slimy texture, indicating that the mushroom’s natural defenses have been compromised. For example, button mushrooms may turn a dull brown, while shiitakes might lose their rich, earthy tone. If you notice any unusual pigmentation, especially paired with slime, it’s best to discard them.

Texture is a telltale indicator of mushroom freshness. Fresh mushrooms should feel firm and slightly spongy to the touch. When they become slimy, their texture softens, and they may feel mushy or watery. This change occurs as the mushroom’s cells break down, releasing moisture and creating a breeding ground for bacteria. If a mushroom feels unusually soft or leaves a residue on your fingers, it’s likely spoiled. Always inspect mushrooms before cooking, and trust your senses—if they feel off, they probably are.

Proper storage can significantly extend mushroom life and prevent spoilage. Store fresh mushrooms in a paper bag or loosely wrapped in a damp cloth in the refrigerator, where they’ll stay fresh for up to a week. Avoid airtight containers, as trapped moisture accelerates slime formation. If you notice early signs of spoilage, such as slight slime or discoloration, you can trim the affected areas and cook the mushrooms immediately. However, if the slime is widespread or accompanied by other spoilage signs, discard them to avoid risk.

Finally, trust your instincts when evaluating mushroom safety. If something seems off—whether it’s an unusual smell, texture, or appearance—it’s better to discard the mushrooms than risk illness. While some slime might be harmless, it’s rarely worth the gamble. When in doubt, follow the adage: “When in doubt, throw it out.” This simple rule can save you from unpleasant consequences and ensure your meals remain safe and enjoyable.

Sorghum as Mushroom Spawn: Innovative Substrate for Fungal Cultivation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Slimy mushrooms are generally not safe to eat. Sliminess can indicate spoilage, bacterial growth, or decomposition, making them potentially harmful if consumed.

Mushrooms become slimy due to excess moisture, bacterial growth, or natural breakdown over time. Improper storage can accelerate this process.

Not all slimy mushrooms are poisonous, but sliminess is a sign of deterioration, which can make even edible mushrooms unsafe to eat.

Cooking slimy mushrooms does not make them safe. The sliminess indicates spoilage, and cooking will not eliminate potential toxins or harmful bacteria.

Store mushrooms in a paper bag or loosely wrapped in a damp cloth in the refrigerator. Avoid plastic bags, as they trap moisture and promote sliminess. Use them within a few days for best quality.