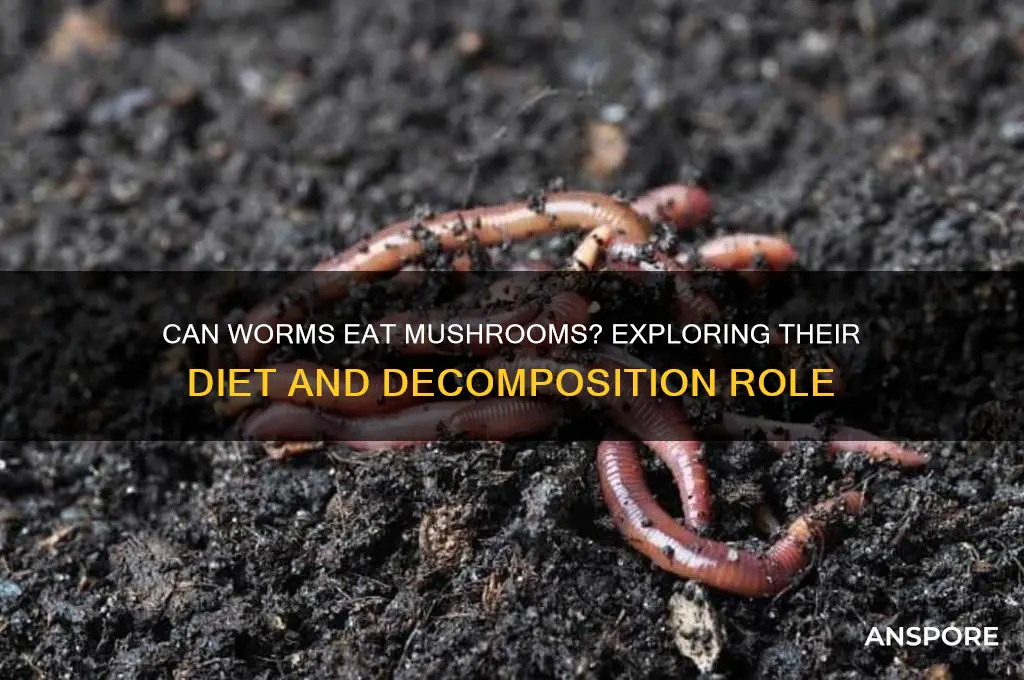

The question of whether worms can eat mushrooms is an intriguing one, as it delves into the dietary habits and ecological roles of these organisms. Earthworms, commonly found in soil, are primarily detritivores, feeding on decaying organic matter such as leaves and plant debris. While their diet is broad, it generally does not include fresh mushrooms, which are fungi rather than plant material. However, some species of worms might consume decomposing mushrooms as part of their natural scavenging behavior. Understanding this relationship is important for both ecological studies and practical applications, such as composting, where worms and mushrooms often coexist in organic environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can worms eat mushrooms? | Yes, some species of worms can eat mushrooms. |

| Worm species that eat mushrooms | Earthworms, compost worms (e.g., red wigglers), and other detritivorous worms. |

| Types of mushrooms consumed | Decomposing mushrooms, both wild and cultivated varieties, such as button mushrooms, oyster mushrooms, and shiitake mushrooms. |

| Nutritional benefits for worms | Mushrooms provide organic matter, fiber, and nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which aid in worm growth and reproduction. |

| Role in decomposition | Worms help break down mushrooms, accelerating the decomposition process and contributing to nutrient cycling in ecosystems. |

| Potential risks | Some mushrooms may be toxic to worms, and consuming large amounts of certain mushroom species could be harmful. |

| Habitat considerations | Worms are more likely to encounter and consume mushrooms in environments with abundant organic matter, such as forests, gardens, and compost piles. |

| Research and studies | Limited specific research on worm-mushroom interactions, but general studies on detritivorous organisms and decomposition processes provide relevant insights. |

| Practical applications | Encouraging worm-mushroom interactions can improve soil health, composting efficiency, and ecosystem functioning. |

| Conservation implications | Understanding worm-mushroom relationships can inform conservation efforts for both worm species and fungal ecosystems. |

Explore related products

$3.99 $6.09

What You'll Learn

- Worm Species and Mushroom Types: Different worms may have varying abilities to consume specific mushroom varieties

- Nutritional Value for Worms: Mushrooms can provide nutrients, but not all are beneficial or safe for worms

- Toxicity Concerns: Some mushrooms are toxic and can harm or kill worms if ingested

- Decomposition Role: Worms aid in breaking down mushrooms, contributing to ecosystem nutrient cycling

- Feeding Behavior: Worms may avoid mushrooms due to texture, taste, or chemical defenses in fungi

Worm Species and Mushroom Types: Different worms may have varying abilities to consume specific mushroom varieties

Worms, often seen as simple decomposers, exhibit surprising diversity in their dietary preferences, particularly when it comes to mushrooms. For instance, the common earthworm (*Lumbricus terrestris*) is known to consume small amounts of mushroom mycelium as part of its soil-dwelling diet, aiding in nutrient cycling. However, not all worms interact with mushrooms in the same way. Mealworms (*Tenebrio molitor*), often used in pet food, have been observed avoiding certain mushroom species due to their toxic compounds, while mushroom-specific nematodes, like *Aphelenchoides* species, actively feed on fungal tissues, sometimes causing damage to cultivated mushrooms. This variation highlights the importance of understanding species-specific behaviors in worm-mushroom interactions.

To explore this further, consider the role of mushroom toxicity in shaping worm diets. Some mushrooms, like the Amanita genus, contain amatoxins lethal to many organisms, including worms. In contrast, non-toxic varieties such as oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are more likely to be consumed by generalist worms. For hobbyists or researchers, testing worm compatibility with mushrooms requires caution: start with small quantities (e.g., 0.1g of mushroom tissue per 10 worms) and observe for 24–48 hours for signs of distress or avoidance. This methodical approach ensures safety while uncovering dietary preferences.

From a practical standpoint, understanding worm-mushroom interactions can benefit composting and agriculture. Red wiggler worms (*Eisenia fetida*), popular in vermicomposting, can break down non-toxic mushroom waste, enriching soil with nutrients. However, pairing them with toxic mushrooms like the death cap (*Amanita phalloides*) could prove fatal. Farmers and composters should source mushroom waste from edible varieties (e.g., shiitake or button mushrooms) to avoid contamination. Additionally, maintaining a balanced carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (25:1) in compost piles encourages worm activity and efficient decomposition.

Comparatively, specialized worms like the mushroom-feeding nematode *Aphelenchoides besseyi* offer insights into co-evolutionary relationships. These nematodes not only consume mushrooms but also act as vectors for fungal diseases, posing risks to mushroom farms. In contrast, earthworms enhance mushroom growth indirectly by aerating soil and improving water retention. This duality underscores the need for targeted management strategies: while generalist worms can be allies in composting, specialized species may require control measures to protect crops.

In conclusion, the ability of worms to consume mushrooms varies widely across species and mushroom types, influenced by factors like toxicity, nutritional content, and ecological roles. By studying these interactions, we can optimize practices in composting, agriculture, and even pest control. Whether you’re a gardener, researcher, or enthusiast, tailoring worm diets to specific mushroom varieties ensures both safety and efficiency. Always prioritize observation and experimentation to unlock the full potential of these fascinating relationships.

Inhaling Mushroom Spores: Debunking Myths and Understanding Potential Risks

You may want to see also

Nutritional Value for Worms: Mushrooms can provide nutrients, but not all are beneficial or safe for worms

Worms, particularly those used in composting or as fishing bait, can indeed consume mushrooms, but the nutritional value and safety of this practice vary widely. Mushrooms are rich in chitin, a complex carbohydrate that worms can break down with the help of microorganisms in their gut. This process can provide worms with essential nutrients like nitrogen and carbon, which are crucial for their growth and reproduction. However, not all mushrooms are created equal. Some species contain toxins or compounds that can harm worms, while others may lack the necessary nutrients to support their health. For example, common button mushrooms (*Agaricus bisporus*) are generally safe and can be a good addition to a worm’s diet when fed in moderation, but wild mushrooms like the Amanita genus should be avoided due to their toxicity.

When incorporating mushrooms into a worm’s diet, it’s essential to consider the type and quantity. Mushrooms should be chopped into small pieces to make them easier for worms to consume and digest. A safe starting point is to offer mushrooms as no more than 10% of their total food intake. Overfeeding mushrooms can lead to imbalances in the worm’s diet, as they lack certain nutrients like proteins and fats that worms require. Additionally, always ensure the mushrooms are fresh and free from mold or pesticides, as these can be harmful. For composting worms, such as red wigglers (*Eisenia fetida*), mushrooms can help diversify their diet and improve the nutrient profile of the resulting castings, but they should be used as a supplement rather than a staple.

The nutritional benefits of mushrooms for worms extend beyond basic sustenance. Mushrooms are a source of antioxidants and enzymes that can support the worm’s immune system and overall health. For example, shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) contain lentinan, a compound known for its immune-boosting properties. However, these benefits are species-specific, and not all mushrooms offer such advantages. It’s also important to note that worms are more efficient at breaking down plant-based materials than fungi, so mushrooms should not replace their primary food sources like fruit and vegetable scraps. Instead, think of mushrooms as a nutritional booster that can enhance their diet when used thoughtfully.

A critical caution is the potential for mushrooms to introduce harmful substances into the worm’s environment. Some mushrooms contain heavy metals or toxins that can accumulate in the worm’s body, especially if the mushrooms were grown in contaminated soil. To mitigate this risk, source mushrooms from reputable suppliers or grow them yourself using clean substrates. Avoid feeding worms wild-harvested mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their safety. Additionally, monitor the worms for any signs of distress, such as reduced activity or unusual behavior, after introducing mushrooms to their diet. If negative effects occur, discontinue feeding mushrooms immediately and revert to their regular diet.

In conclusion, while mushrooms can provide nutritional benefits to worms, their inclusion in a worm’s diet requires careful consideration. By selecting safe mushroom species, controlling portion sizes, and ensuring quality, you can harness the potential of mushrooms to enhance worm health and productivity. Whether you’re a composter, angler, or worm enthusiast, understanding the nuances of feeding mushrooms to worms can help you make informed decisions that benefit both the worms and their environment. Always prioritize safety and balance to ensure the well-being of these valuable organisms.

Reheating Cooked Mushrooms: Tips for Safe and Delicious Results

You may want to see also

Toxicity Concerns: Some mushrooms are toxic and can harm or kill worms if ingested

Worms, often seen as nature's recyclers, play a crucial role in breaking down organic matter. However, their indiscriminate appetite can lead them to consume mushrooms, some of which are highly toxic. Unlike mammals, worms lack the complex digestive systems to neutralize certain fungal toxins, making them particularly vulnerable. For instance, mushrooms containing amatoxins, such as those in the *Amanita* genus, can cause severe liver damage in worms even in minute quantities. Understanding this risk is essential for anyone maintaining worm bins or studying their behavior in natural habitats.

To mitigate toxicity concerns, it’s imperative to identify and remove harmful mushrooms from environments where worms are present. Common toxic species include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), both of which are lethal in small doses. A practical tip is to regularly inspect compost piles, gardens, or worm habitats for unfamiliar fungi, especially after rainy periods when mushrooms thrive. If unsure about a mushroom’s identity, err on the side of caution and remove it entirely. Prevention is far easier than treating poisoned worms, which often show symptoms like lethargy, discoloration, or death within hours of ingestion.

Comparing worm toxicity to human risks highlights the need for vigilance. While humans can experience severe symptoms from toxic mushrooms, worms are more susceptible due to their size and physiology. For example, a single Death Cap mushroom can be fatal to a small population of worms, whereas a human might require a larger dose to exhibit symptoms. This disparity underscores the importance of creating a controlled environment for worms, especially in vermicomposting systems. By eliminating toxic mushrooms, you not only protect the worms but also ensure the safety of the compost they produce.

Instructing worm enthusiasts on safe practices involves a combination of awareness and proactive measures. First, educate yourself on local toxic mushroom species through field guides or online resources. Second, maintain a clean habitat by regularly turning compost and removing any fungal growth. Third, consider using a mesh cover to prevent wild mushrooms from colonizing the area. For those raising worms indoors, sourcing mushroom-free bedding materials is crucial. By adopting these steps, you can minimize the risk of toxicity and create a thriving environment for your worms.

Finally, the takeaway is clear: while worms can technically eat mushrooms, not all mushrooms are safe for them. Toxic species pose a significant threat, and their presence in worm habitats should never be ignored. By staying informed, vigilant, and proactive, you can protect these vital organisms and ensure their continued contribution to soil health and composting efforts. Remember, a little prevention goes a long way in safeguarding both worms and the ecosystems they support.

Exploring the Possibility: Can Mushrooms Thrive in Ocean Environments?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Decomposition Role: Worms aid in breaking down mushrooms, contributing to ecosystem nutrient cycling

Worms, often overlooked in the grand tapestry of ecosystems, play a pivotal role in the decomposition of organic matter, including mushrooms. These subterranean creatures are nature’s recyclers, breaking down complex materials into simpler forms that enrich the soil. When a mushroom falls to the forest floor, worms are among the first to engage with it, initiating a process that transforms decay into renewal. This interaction is not merely a feeding behavior but a critical step in nutrient cycling, ensuring that essential elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon are returned to the ecosystem.

Consider the mechanics of this process: worms ingest mushroom fragments, along with soil and other organic debris, through their mouths. Inside their digestive systems, enzymes break down the tough chitinous cell walls of mushrooms, which are otherwise resistant to many decomposers. The resulting waste, known as worm castings, is nutrient-dense and acts as a slow-release fertilizer. For gardeners or ecologists, this means that encouraging worm activity in mushroom-rich areas can significantly enhance soil fertility. A practical tip: adding a layer of leaf litter or compost to your garden beds can attract worms and create an environment conducive to mushroom decomposition.

The ecological impact of this relationship extends beyond soil enrichment. By accelerating the breakdown of mushrooms, worms prevent the accumulation of organic matter that could otherwise inhibit plant growth. This is particularly important in forests, where fallen mushrooms contribute to the detrital food web. For instance, a study in temperate woodlands found that earthworms increased the rate of mushroom decomposition by up to 40%, highlighting their efficiency as decomposers. This efficiency is not just a biological curiosity but a vital service that supports biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

However, the role of worms in mushroom decomposition is not without nuance. Different worm species exhibit varying preferences and capabilities. For example, epigeic worms, which live in organic-rich topsoil, are more likely to consume mushrooms than endogeic or anecic species, which inhabit deeper soil layers. Understanding these distinctions can inform conservation efforts, such as selecting appropriate worm species for habitat restoration projects. Additionally, the presence of toxins in certain mushrooms may deter worm activity, underscoring the importance of species-specific interactions in decomposition dynamics.

In conclusion, the decomposition role of worms in breaking down mushrooms is a fascinating and functional aspect of ecosystem nutrient cycling. By facilitating the transformation of mushrooms into usable nutrients, worms not only sustain soil health but also contribute to the broader balance of ecological systems. Whether you’re a gardener seeking to improve soil fertility or an ecologist studying forest dynamics, recognizing the value of this worm-mushroom interaction can inspire more informed and sustainable practices. After all, in the intricate web of life, even the smallest creatures can have the largest impacts.

Can Reishi Mushrooms Induce a High? Debunking Myths and Facts

You may want to see also

Feeding Behavior: Worms may avoid mushrooms due to texture, taste, or chemical defenses in fungi

Worms, primarily earthworms, are often observed avoiding mushrooms in their environment, a behavior that raises questions about their feeding preferences. This avoidance is not arbitrary but likely stems from specific sensory and physiological factors. Earthworms rely heavily on their sense of touch and taste to navigate and select food. Mushrooms, with their spongy or fibrous textures, may not align with the softer, more decomposed organic matter worms typically consume. For instance, the tough cell walls of fungi, composed of chitin, could be less appealing or harder to process for worms, which prefer easily digestible materials like leaf litter and soil organic matter.

Chemical defenses in fungi present another layer of complexity. Many mushrooms produce secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids or terpenes, which can deter herbivores. While these compounds are often targeted at larger organisms, they may still influence worms. Studies suggest that even small concentrations of certain fungal toxins can disrupt worm feeding behavior. For example, exposure to mycotoxins like patulin or gliotoxin, commonly found in decomposing mushrooms, has been shown to reduce worm activity and feeding rates. This chemical aversion could explain why worms bypass mushrooms in favor of safer, more palatable food sources.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this behavior is crucial for gardeners and composters. If you’re aiming to enhance worm activity in your compost pile, avoid adding large quantities of mushrooms, especially those in advanced stages of decomposition. Instead, focus on providing worms with their preferred diet: shredded paper, vegetable scraps, and well-rotted plant material. For those experimenting with vermicomposting, monitor worm behavior when introducing new organic matter, and remove any items that appear to deter feeding. This ensures a healthy, active worm population and more efficient composting.

Comparatively, other soil organisms like slugs and millipedes exhibit different feeding patterns with mushrooms, often consuming them without issue. This highlights the specificity of worm aversion to fungi. While worms may avoid mushrooms due to texture or chemical defenses, these factors do not universally apply to all soil fauna. Such differences underscore the importance of tailoring soil management practices to the unique needs of each organism. By respecting these preferences, we can create more balanced and productive ecosystems, whether in a garden or compost bin.

In conclusion, worms’ avoidance of mushrooms is a nuanced behavior driven by texture, taste, and chemical defenses in fungi. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of worm ecology but also provides actionable insights for practical applications. By aligning our practices with worm preferences, we can foster healthier soil environments and more efficient composting systems. Observing and adapting to these behaviors ensures that worms remain effective allies in nutrient cycling and soil health.

Using Bottled Mushrooms in Crock Pot Recipes: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, worms can eat mushrooms, but it depends on the type of worm and mushroom. Earthworms, for example, can consume decomposing mushrooms as part of their natural diet.

Generally, mushrooms are safe for worms, especially if they are decomposing or non-toxic varieties. However, avoid feeding worms toxic or poisonous mushrooms, as they can harm the worms.

Yes, worms can benefit from eating mushrooms as they provide organic matter and nutrients. Mushrooms contribute to the worms' diet and aid in the decomposition process in their environment.

Not all worms eat mushrooms. Earthworms and some composting worms are more likely to consume mushrooms, while other species may not be interested or able to digest them. Always research the specific worm species before feeding them mushrooms.