The concept of being immune to mushrooms is an intriguing topic that blends immunology, mycology, and nutrition. While mushrooms are generally considered safe and even beneficial for most people due to their rich nutrient profile and potential health-promoting properties, some individuals may experience adverse reactions, such as allergies or intolerances. True immunity to mushrooms, in the sense of being completely unaffected by their biological components, is not a recognized phenomenon. However, certain individuals may have genetic or physiological traits that make them less susceptible to mushroom-related issues, such as toxic reactions from wild mushrooms or allergic responses. Understanding the mechanisms behind these reactions and the variability in human responses to mushrooms can shed light on how our bodies interact with these fascinating fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Immunity to Mushrooms | Not a recognized medical condition; no evidence of complete immunity to all mushroom types. |

| Allergies | Some individuals may develop allergies to specific mushroom species, causing symptoms like itching, swelling, or digestive issues. |

| Toxin Resistance | No known genetic or acquired resistance to mushroom toxins (e.g., amatoxins, muscarine). Poisoning still possible. |

| Immune Response | The immune system can react to mushroom proteins, but this does not confer immunity to toxins or prevent poisoning. |

| Tolerance | Repeated exposure to certain mushrooms may reduce sensitivity in some individuals, but this is not immunity. |

| Medical Use | Some mushrooms (e.g., medicinal mushrooms like Reishi or Chaga) may modulate the immune system but do not provide immunity to other mushrooms. |

| Myths | Claims of immunity to mushrooms are anecdotal and lack scientific evidence. |

| Prevention | Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless properly identified by an expert to prevent poisoning. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Allergic Reactions to Mushrooms: Some individuals may develop allergies, but true immunity is rare

- Mycophobia and Avoidance: Psychological aversion to mushrooms, not biological immunity

- Toxin Resistance in Humans: Certain toxins in mushrooms can be resisted, not immunity

- Immune System Response: The body may tolerate or react to mushroom proteins

- Cultural and Dietary Factors: Habits and exposure influence tolerance, not immunity

Allergic Reactions to Mushrooms: Some individuals may develop allergies, but true immunity is rare

Mushrooms, whether in a creamy risotto or as a dietary supplement, are a staple in many diets worldwide. However, not everyone reacts to them the same way. While some individuals may experience allergic reactions, the concept of true immunity to mushrooms is rare and often misunderstood. Allergies to mushrooms typically manifest as skin rashes, itching, swelling, or gastrointestinal discomfort, with symptoms appearing within minutes to hours after consumption. These reactions are triggered by proteins in mushrooms that the immune system mistakenly identifies as harmful.

Understanding the difference between an allergy and immunity is crucial. An allergy is an overreaction of the immune system to a specific substance, whereas immunity refers to the body’s ability to resist or tolerate that substance entirely. True immunity to mushrooms would mean the body neither reacts adversely nor benefits from their consumption, which is uncommon. Most people who avoid mushrooms due to perceived immunity are likely experiencing allergies or sensitivities. For instance, individuals with mold allergies may cross-react to mushrooms due to shared proteins, a phenomenon known as oral allergy syndrome.

For those suspecting a mushroom allergy, consulting an allergist for testing is essential. Skin prick tests or blood tests can identify specific allergens, and oral food challenges may confirm the diagnosis. If an allergy is confirmed, strict avoidance is the primary management strategy. However, this doesn’t mean all mushrooms are off-limits; some varieties may still be tolerated. Cooking mushrooms can also denature allergenic proteins, reducing the risk of reaction in mild cases. Always consult a healthcare provider before reintroducing mushrooms into your diet.

Children and adults alike can develop mushroom allergies, though onset often occurs in adulthood. Interestingly, repeated exposure to mushrooms in cooking or environmental settings may increase sensitivity over time. For those with severe allergies, carrying an epinephrine auto-injector is critical, as anaphylaxis, though rare, is a potential risk. Practical tips include reading food labels carefully, as mushrooms can be hidden in sauces, soups, and processed foods. Additionally, informing restaurants about your allergy can prevent accidental exposure.

In summary, while allergic reactions to mushrooms are real and can be managed, true immunity is a rarity. Recognizing symptoms, seeking proper diagnosis, and adopting preventive measures are key to safely navigating mushroom consumption. Whether you’re a chef, a health-conscious eater, or someone with a suspected allergy, understanding this distinction ensures informed decisions about including mushrooms in your diet.

Can You Eat Mushroom Fins? Exploring Edible Fungus Parts Safely

You may want to see also

Mycophobia and Avoidance: Psychological aversion to mushrooms, not biological immunity

While biological immunity to mushrooms is rare, mycophobia—an intense fear or aversion to fungi—is a psychological phenomenon that affects a significant number of individuals. Unlike an immune response, which involves the body’s defense mechanisms, mycophobia stems from cognitive and emotional factors, often rooted in cultural, experiential, or evolutionary influences. For example, many Western cultures historically portrayed mushrooms as poisonous or associated them with decay, leading to widespread unease. This aversion is not about physical tolerance but rather a learned or instinctive avoidance behavior. Understanding this distinction is crucial, as it highlights the role of the mind in shaping dietary preferences and behaviors.

Consider the case of a 35-year-old individual who avoids mushrooms despite no history of allergic reaction or illness. Their aversion might stem from childhood exposure to negative narratives about mushrooms, such as being told they are "dangerous" or "dirty." Over time, this conditioning can manifest as a visceral dislike, even when presented with safe, edible varieties. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, such as gradual exposure and reframing beliefs, can help such individuals challenge their fears. For instance, starting with visual exposure (e.g., pictures of mushrooms) and progressing to handling or tasting small amounts under supervision can desensitize the aversion. Practical tips include pairing mushrooms with familiar, liked foods to create positive associations.

From a comparative perspective, mycophobia contrasts sharply with mycophilia—a love or fascination with mushrooms—seen in cultures like those in East Asia and Eastern Europe, where fungi are celebrated as culinary delicacies and medicinal treasures. This divergence underscores the cultural relativity of food aversions. For instance, while truffle mushrooms are prized in Italy, they might be met with skepticism in regions where mushroom consumption is uncommon. By examining these cultural differences, we can see that mycophobia is not universal but rather a product of specific societal narratives and experiences. Encouraging cross-cultural education about mushrooms could help reduce unfounded fears.

Finally, it’s essential to differentiate mycophobia from legitimate health concerns, such as mushroom allergies or sensitivities. While true allergies are rare, affecting less than 1% of the population, symptoms like itching, swelling, or digestive issues should not be ignored. Individuals with a history of mold allergies may also experience cross-reactivity to certain mushrooms. For those unsure, consulting an allergist for testing is advisable. However, for the majority of mycophobes, the aversion is psychological, and addressing it through education, exposure, and mindful practices can open doors to a broader, more inclusive diet. After all, mushrooms are not just a food—they are a gateway to understanding the complex interplay between mind, culture, and palate.

Storing Magic Mushrooms: Room Temperature Tips and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Toxin Resistance in Humans: Certain toxins in mushrooms can be resisted, not immunity

Humans cannot develop immunity to mushroom toxins, but certain populations exhibit resistance to specific fungal poisons. For instance, the Amanita phalloides mushroom contains amatoxins, which inhibit RNA polymerase II and cause severe liver damage. However, individuals with genetic variations in their CYP2D6 enzyme, responsible for metabolizing toxins, may process amatoxins more efficiently, reducing their susceptibility to acute toxicity. This genetic resistance is not immunity but rather a mitigated response to the toxin's effects.

To understand toxin resistance, consider the case of orellanine, found in Cortinarius mushrooms. This toxin causes delayed renal failure by accumulating in kidney tissue. Chronic exposure to low doses of orellanine in certain European populations has led to increased glomerular filtration rates, a compensatory mechanism that delays toxin-induced damage. While this does not confer immunity, it highlights the body’s ability to adapt to repeated, sublethal exposure. Practical tip: Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless positively identified by an expert, as even resistant individuals face risks from high doses or novel toxins.

Resistance mechanisms vary by toxin type and human physiology. For example, ibotenic acid in Amanita muscaria mushrooms acts as a neurotoxin by binding to glutamate receptors. Some individuals may develop tolerance through downregulation of these receptors after repeated exposure, reducing psychoactive effects. However, this tolerance is toxin-specific and does not protect against other mushroom poisons like muscarine or coprine. Analytical takeaway: Resistance is a dynamic, toxin-specific process, not a blanket immunity to all mushroom compounds.

Building resistance to mushroom toxins is neither safe nor recommended. Instead, focus on prevention. For accidental ingestion, immediate steps include inducing vomiting (if within 1-2 hours) and seeking medical attention. Activated charcoal may bind toxins in the gut, but its effectiveness varies by toxin. Hospitals use specific antidotes like silibinin for amatoxins or hemodialysis for orellanine poisoning. Caution: Do not rely on home remedies or folklore; always consult healthcare professionals for suspected mushroom poisoning.

In summary, while humans cannot achieve immunity to mushroom toxins, certain genetic, physiological, and adaptive mechanisms can reduce susceptibility to specific poisons. This resistance is limited, toxin-specific, and does not replace the need for caution. Practical advice: Educate yourself on local mushroom species, avoid foraging without expertise, and prioritize professional identification to minimize risks. Resistance is a biological nuance, not a license to experiment with potentially deadly fungi.

Marinating Whole Jarred Mushrooms: Tips, Tricks, and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Immune System Response: The body may tolerate or react to mushroom proteins

The human immune system is a complex network designed to distinguish between self and non-self, but its response to mushrooms is not uniform. Mushroom proteins, like any foreign substance, can trigger varying reactions depending on individual immune profiles. For instance, some people may consume mushrooms regularly without issue, while others experience allergic reactions ranging from mild itching to anaphylaxis. This disparity highlights the immune system’s ability to either tolerate or react to these proteins, influenced by factors such as genetic predisposition, exposure history, and overall immune health. Understanding this variability is crucial for predicting and managing potential adverse responses.

To illustrate, consider the case of shiitake mushrooms, which contain a protein called lentinan. While lentinan is celebrated for its immune-boosting properties in many individuals, it can also cause shiitake dermatitis in others, a skin reaction characterized by rashes and itching. This dual effect underscores the immune system’s nuanced response to mushroom proteins. Dosage plays a critical role here; consuming large quantities of shiitake mushrooms, especially raw or undercooked, increases the likelihood of an adverse reaction. Practical advice includes cooking mushrooms thoroughly to denature potentially reactive proteins and starting with small portions to gauge tolerance.

From a comparative perspective, the immune response to mushrooms mirrors reactions to other food allergens, such as peanuts or shellfish. However, mushrooms present a unique challenge due to their classification as fungi, which share some molecular similarities with pathogens. This can lead to cross-reactivity in individuals with mold allergies, as the immune system mistakenly identifies mushroom proteins as harmful. For example, a study published in the *Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology* found that 30% of mold-allergic patients also reacted to mushroom extracts. Such findings emphasize the importance of allergy testing for at-risk individuals, particularly those with a history of fungal or mold sensitivities.

Persuasively, it’s worth advocating for personalized dietary approaches when incorporating mushrooms. For children and the elderly, whose immune systems are more vulnerable, gradual introduction and monitoring are essential. Adults with pre-existing allergies or autoimmune conditions should consult healthcare providers before experimenting with exotic mushroom varieties. Additionally, keeping a food diary can help identify patterns between mushroom consumption and immune responses, enabling proactive management. By adopting these measures, individuals can safely explore the nutritional benefits of mushrooms while minimizing risks.

In conclusion, the immune system’s response to mushroom proteins is a delicate balance between tolerance and reactivity, shaped by individual factors and exposure conditions. Practical steps, such as mindful consumption and allergy awareness, can mitigate potential risks. As research continues to unravel the complexities of this interaction, informed decision-making remains the key to harnessing mushrooms’ benefits without compromising health.

Can Drug Dogs Detect Magic Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

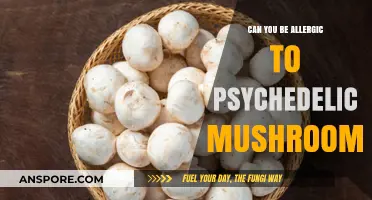

Cultural and Dietary Factors: Habits and exposure influence tolerance, not immunity

The concept of being "immune" to mushrooms is a misnomer. Our bodies don't develop immunity to them in the same way we might to a virus or bacteria. Instead, tolerance to mushrooms, particularly those containing compounds like psilocybin or allergens, is shaped by cultural practices and dietary habits. For instance, in regions like Oaxaca, Mexico, where psychedelic mushrooms are integrated into spiritual rituals, individuals often consume them in controlled, ceremonial doses (typically 1-3 grams dried) under the guidance of experienced facilitators. This repeated, mindful exposure fosters a familiarity that reduces adverse reactions, not through biological immunity but through learned tolerance and psychological preparation.

Consider the role of dietary exposure in allergenic responses. In Japan, shiitake mushrooms are a dietary staple, consumed regularly in amounts ranging from 50-100 grams per week. Studies show that populations with high shiitake intake are less likely to develop allergic reactions, such as "shiitake dermatitis," compared to those encountering them sporadically. This isn’t immunity—it’s desensitization through consistent, low-level exposure. For those introducing shiitake into their diet, start with small portions (10-20 grams) twice weekly, gradually increasing to build tolerance while monitoring for itching or rashes.

Contrast this with Western cultures, where mushroom consumption is often limited to button or portobello varieties, and exotic species like morels or chanterelles are treated as novelties. In these contexts, infrequent exposure can heighten sensitivity to both allergens and psychoactive compounds. For example, a first-time consumer of psilocybin mushrooms might experience overwhelming anxiety if they ingest a recreational dose (2-3.5 grams) without prior experience. Cultural practices in psychedelic-friendly societies emphasize microdosing (0.1-0.3 grams) or communal settings, which mitigate risks by normalizing the experience and reducing psychological resistance.

Practical takeaways abound for those navigating mushroom consumption. If exploring psychoactive varieties, follow the "start low, go slow" principle, especially in cultures where such use is uncommon. For allergenic concerns, introduce new mushroom types in minimal quantities (5-10 grams cooked) and pair them with familiar foods to gauge reactions. Cultural rituals, like the Russian tradition of pickling wild mushrooms, not only preserve them but also alter their chemical composition, potentially reducing allergenicity. Emulate these practices by fermenting or cooking mushrooms thoroughly to break down irritant proteins.

Ultimately, tolerance to mushrooms is a product of context, not biology. Whether through ceremonial use, dietary staples, or culinary techniques, repeated, intentional exposure shapes how our bodies respond. Immunity is a myth; adaptation is the reality. By adopting habits from cultures with deep mushroom traditions, individuals can safely expand their dietary and experiential horizons, turning the unfamiliar into the manageable.

Psychedelic Mushrooms: A Potential Treatment for Essential Tremor?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, immunity to mushrooms in the sense of becoming resistant to their effects is not scientifically recognized. However, some individuals may develop allergies or sensitivities to certain types of mushrooms, which can cause adverse reactions.

There is no evidence to suggest that individuals can be naturally immune to mushroom poisoning. Consuming toxic mushrooms can be dangerous for anyone, regardless of their genetic makeup or prior exposure.

Repeated exposure to mushrooms does not confer immunity to their toxins. In fact, repeated ingestion of toxic mushrooms can increase the risk of severe poisoning or long-term health issues. Always exercise caution and properly identify mushrooms before consumption.