The question of whether you can change from bats to mushrooms may seem absurd at first glance, as these two organisms belong to entirely different biological kingdoms—bats are mammals, while mushrooms are fungi. However, this inquiry opens up fascinating discussions about transformation, evolution, and the boundaries of biological possibility. While direct metamorphosis from a bat to a mushroom is scientifically impossible due to their vastly different genetic and cellular structures, exploring this idea can lead to insights into topics like genetic engineering, symbiotic relationships, or even metaphorical transformations in nature. It also highlights the diversity and complexity of life on Earth, reminding us of the intricate ways organisms adapt and evolve within their ecosystems.

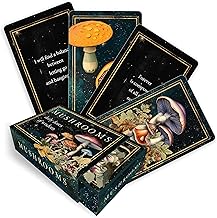

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Taxonomic Differences: Bats are mammals; mushrooms are fungi, distinct kingdoms with unique cellular structures

- Evolutionary Paths: Bats evolved from mammals; mushrooms from fungi, unrelated evolutionary histories

- Biological Functions: Bats are heterotrophs; mushrooms decompose matter, different ecological roles

- Genetic Barriers: No shared genetic material; transformation is biologically impossible

- Metamorphosis Myths: No natural or scientific process allows bats to become mushrooms

Taxonomic Differences: Bats are mammals; mushrooms are fungi, distinct kingdoms with unique cellular structures

Bats and mushrooms, though both fascinating organisms, belong to entirely distinct biological kingdoms: Animalia and Fungi, respectively. This fundamental taxonomic difference underscores their unique evolutionary paths and cellular structures. Mammals, like bats, are characterized by eukaryotic cells with nuclei, complex tissues, and the ability to regulate body temperature internally. Fungi, such as mushrooms, also possess eukaryotic cells but lack chlorophyll and obtain nutrients through absorption rather than ingestion. This cellular distinction is the cornerstone of their biological divergence.

Consider the structural differences: bats have multicellular bodies with specialized organs, including a skeletal system, circulatory system, and brain. Mushrooms, in contrast, consist of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which form the mycelium, and their fruiting bodies are the visible part we recognize as mushrooms. These structural disparities reflect their roles in ecosystems—bats as active predators and pollinators, mushrooms as decomposers and symbionts. Understanding these differences is crucial for appreciating the complexity of life’s diversity.

From a practical standpoint, the taxonomic gap between bats and mushrooms means there is no biological mechanism for one to transform into the other. While genetic engineering has made remarkable strides, altering an organism’s kingdom-level classification remains beyond current capabilities. For instance, attempts to introduce fungal traits into mammals or vice versa would require rewriting vast portions of their genetic code, a task fraught with ethical and technical challenges. Thus, the idea of "changing" from a bat to a mushroom remains firmly in the realm of science fiction.

To illustrate the impossibility, imagine trying to convert a mammal’s digestive system, which relies on ingestion and internal processing, into a fungal absorptive system. This would necessitate altering cellular metabolism, nutrient acquisition pathways, and even the organism’s ecological role. Similarly, transforming a fungus into a mammal would require the development of organs, sensory systems, and a nervous system—a feat far beyond current scientific tools. These examples highlight the profound taxonomic and biological barriers between bats and mushrooms.

In conclusion, the taxonomic differences between bats and mushrooms are not merely academic but represent fundamental biological realities. Their distinct cellular structures, ecological roles, and evolutionary histories make any transformation between the two biologically implausible. While scientific advancements continue to push boundaries, the gap between Animalia and Fungi remains a testament to the intricate and unyielding nature of life’s classification.

Can Mushroom Overconsumption Cause Thrush? Exploring the Fungal Connection

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Paths: Bats evolved from mammals; mushrooms from fungi, unrelated evolutionary histories

Bats and mushrooms, though both fascinating organisms, trace their origins to entirely distinct evolutionary lineages. Bats, as mammals, share a common ancestry with creatures like whales, dogs, and humans, emerging from the synapsid lineage over 60 million years ago. Their evolution is marked by adaptations for flight, echolocation, and nocturnal lifestyles. In contrast, mushrooms belong to the kingdom Fungi, a group that diverged from animals over a billion years ago. Fungi evolved unique traits such as chitinous cell walls and heterotrophic nutrition, leading to their role as decomposers and symbionts in ecosystems. This fundamental divide underscores why transitioning from a bat to a mushroom is biologically impossible—their evolutionary paths are not just different but rooted in incompatible biological frameworks.

To illustrate the disparity, consider the cellular level. Bats, like all mammals, are composed of eukaryotic cells with complex organelles, including a nucleus and mitochondria. Their genetic material is organized into linear chromosomes, and they reproduce sexually. Mushrooms, however, are fungi with cells that often lack a nucleus in their hyphae, and their genetic material can be circular or linear. Fungi reproduce through spores, and their metabolism relies on absorbing nutrients externally. These differences are not superficial but reflect deep-seated evolutionary strategies that cannot be bridged by any known biological mechanism. For instance, no genetic engineering technique exists to rewrite a mammal’s cellular structure to mimic that of a fungus, nor can a mammal’s metabolism be altered to function like a fungus’s.

From a practical standpoint, the idea of transforming a bat into a mushroom is not just scientifically implausible but also ethically and ecologically problematic. Bats play critical roles in pollination, insect control, and seed dispersal, while mushrooms are vital for nutrient cycling and soil health. Attempting such a transformation would disrupt these ecological functions, with cascading effects on biodiversity. Moreover, the energy and resources required for such an experiment would far outweigh any potential benefits. Instead, conservation efforts should focus on preserving both bats and mushrooms in their natural forms, ensuring their continued contributions to ecosystems.

A comparative analysis highlights the beauty of their separate evolutionary journeys. Bats’ transition from terrestrial to aerial life showcases the power of natural selection in shaping novel adaptations, such as wings evolved from elongated fingers. Mushrooms, on the other hand, exemplify the success of a decentralized, network-based life form, with mycelium spreading underground to support entire forests. These distinct trajectories remind us of the diversity of life’s strategies and the importance of respecting these differences. Rather than seeking to merge them, we can learn from their unique strengths to inspire innovations in fields like biomimicry and sustainable agriculture.

In conclusion, the question of whether one can change from a bat to a mushroom serves as a thought-provoking reminder of the boundaries set by evolutionary history. While science continues to push the limits of what’s possible, some transformations remain beyond reach due to the fundamental incompatibility of biological systems. Embracing this reality allows us to appreciate the richness of life’s diversity and focus on preserving the unique roles each organism plays in the natural world.

Exploring Alpine Habitats: Can Mushrooms Thrive in High-Altitude Environments?

You may want to see also

Biological Functions: Bats are heterotrophs; mushrooms decompose matter, different ecological roles

Bats and mushrooms, though seemingly disparate, share a common thread in their ecological significance, yet their biological functions diverge sharply. Bats, as heterotrophs, rely on consuming other organisms for energy, primarily feasting on insects, nectar, or fruit. This predatory or symbiotic role positions them as key players in pest control, pollination, and seed dispersal. For instance, a single bat can consume up to 1,000 mosquitoes per hour, making them invaluable in reducing insect-borne diseases. In contrast, mushrooms operate as decomposers, breaking down dead organic matter into simpler substances. This fungal function recycles nutrients back into ecosystems, ensuring soil fertility and sustaining plant life. While bats actively hunt or forage, mushrooms passively transform decay into renewal, highlighting their distinct yet complementary roles in the natural world.

Consider the ecological impact of these roles through a practical lens. If you’re a gardener, attracting bats can reduce pest populations without chemical pesticides. Install bat boxes at least 12 feet high, near water sources, and ensure a clear flight path. For mushrooms, incorporating mycorrhizal fungi into your soil can enhance nutrient uptake for plants. Mix 1-2 tablespoons of mycorrhizal inoculant per plant during planting, ensuring the roots make direct contact with the fungi. These strategies leverage the unique functions of bats and mushrooms to create a balanced, thriving ecosystem.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the heterotrophic nature of bats and the decomposing role of mushrooms reflect specialized adaptations to their environments. Bats’ echolocation and winged flight evolved to optimize hunting efficiency, while mushrooms developed intricate mycelial networks to maximize decomposition. These adaptations underscore the principle of niche differentiation, where organisms evolve distinct functions to minimize competition and maximize resource utilization. By studying these differences, scientists gain insights into biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, emphasizing the importance of preserving both heterotrophs and decomposers.

A persuasive argument for conservation emerges when considering the irreplaceable roles of bats and mushrooms. Bats contribute an estimated $3.7 billion annually to the U.S. agricultural economy through pest control, while mushrooms underpin forest health by decomposing up to 90% of leaf litter in some ecosystems. Yet, both face threats—bats from habitat loss and white-nose syndrome, mushrooms from deforestation and soil degradation. Protecting these organisms isn’t just an ecological imperative; it’s an economic and ethical one. Support bat conservation initiatives, such as habitat restoration, and advocate for sustainable forestry practices to safeguard fungal ecosystems. The survival of bats and mushrooms is intertwined with our own, making their preservation a shared responsibility.

Finally, a comparative analysis reveals the interconnectedness of these seemingly disparate organisms. While bats and mushrooms fulfill different ecological roles, their functions converge in sustaining life. Bats facilitate growth by controlling pests and aiding pollination, while mushrooms ensure the cycle of decay and renewal. Together, they exemplify the delicate balance of ecosystems, where every organism, regardless of its role, contributes to the whole. Understanding this interdependence fosters a deeper appreciation for biodiversity and inspires actions that protect all forms of life, from the winged hunters of the night to the silent decomposers beneath our feet.

Cream of Mushroom Sauce: A Diabetic-Friendly Option or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Barriers: No shared genetic material; transformation is biologically impossible

The genetic chasm between bats and mushrooms is absolute. Unlike animals, which share a common ancestor and a unified genetic code, fungi like mushrooms operate on a fundamentally different biological blueprint. Bats possess linear chromosomes housed within a membrane-bound nucleus, while mushrooms rely on a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, often with circular DNA molecules. This architectural disparity extends to the very language of their genes: the genetic code itself. Codons, the three-letter sequences that dictate amino acid assembly, can vary between kingdoms, meaning a gene from a bat might be unintelligible gibberish to a mushroom’s cellular machinery.

Even if we could overcome the structural hurdles, the functional incompatibility would remain insurmountable. Bats are eukaryotic heterotrophs, relying on complex organ systems and a diet of insects or fruit. Mushrooms, as decomposers, secrete enzymes to break down organic matter externally, absorbing nutrients directly through their cell walls. Their metabolic pathways, cell wall composition, and reproductive strategies are entirely alien to mammalian biology. Attempting to merge these systems would be akin to rewiring a jet engine to run on photosynthesis.

Consider the example of horizontal gene transfer, a process where organisms exchange genetic material without reproduction. While common in bacteria, it’s exceedingly rare across kingdom boundaries. For instance, a 2015 study identified a few bacterial genes in the genome of a mushroom species, likely acquired over millennia through environmental exposure. However, these were simple metabolic genes, not complex developmental programs. The leap from a bat’s wing development gene to a mushroom’s fruiting body formation would require not just gene transfer, but a complete rewriting of the recipient’s genetic operating system.

Proponents of radical genetic engineering might suggest CRISPR-based approaches, but even this technology has limits. CRISPR relies on homology-directed repair, requiring a template sequence with sufficient similarity to the target genome. With bats and mushrooms, there’s no such template. Moreover, editing thousands of genes simultaneously, as required for a species transformation, would introduce unpredictable mutations and likely result in non-viable organisms. The energy and resource requirements alone would be astronomical, far exceeding any potential benefit.

The takeaway is clear: while genetic engineering continues to push boundaries, transforming a bat into a mushroom remains squarely in the realm of science fiction. The genetic barriers are not just high—they’re insurmountable with our current understanding of biology. Instead of chasing impossible transformations, researchers should focus on leveraging these differences to develop cross-kingdom biotechnologies, such as using fungal enzymes to break down mammalian waste or engineering bat-inspired antiviral compounds. The true innovation lies not in defying nature’s boundaries, but in understanding and harnessing them.

Freezing Mushrooms: A Complete Guide to Preserving Freshness and Flavor

You may want to see also

Metamorphosis Myths: No natural or scientific process allows bats to become mushrooms

Bats and mushrooms, though both fascinating organisms, belong to entirely different biological kingdoms—Animalia and Fungi, respectively. This fundamental distinction underscores the impossibility of a bat transforming into a mushroom through any natural or scientific process. Metamorphosis, a biological process observed in certain animals like butterflies and frogs, involves a series of developmental stages within the same species. However, it does not bridge the evolutionary chasm between animals and fungi. Understanding this boundary is crucial for dispelling myths and appreciating the unique characteristics of each organism.

From a scientific perspective, the cellular structures of bats and mushrooms are incompatible. Bats are multicellular eukaryotes with specialized tissues, organs, and a nervous system, while mushrooms are composed of chitinous cell walls and lack mobility or sensory organs. Genetic engineering, though advanced, cannot rewrite the entire blueprint of an organism to switch kingdoms. Even theoretical approaches like CRISPR face insurmountable challenges, as they cannot alter millions of years of evolutionary divergence. Thus, the idea of a bat-to-mushroom transformation remains firmly in the realm of science fiction.

Myths of such transformations often stem from cultural or symbolic interpretations rather than biological reality. In folklore, shape-shifting creatures abound, but these stories serve metaphorical purposes, exploring themes of change and identity. For instance, indigenous tales of animals transforming into plants often symbolize harmony with nature, not literal biological processes. Separating these symbolic narratives from scientific fact is essential for fostering a clear understanding of biology and ecology.

Practically speaking, attempts to merge bats and mushrooms would yield no tangible results. For example, if one were to expose a bat to mushroom spores, the spores would not colonize the bat’s body in a transformative way; instead, they might decompose the bat post-mortem, as fungi do with organic matter. Similarly, injecting fungal DNA into a bat would not initiate a metamorphosis but could lead to infection or death. These scenarios highlight the importance of respecting biological boundaries and focusing on conservation efforts for both bats and fungi, rather than pursuing impossible transformations.

In conclusion, the myth of bats becoming mushrooms serves as a reminder of the diversity and complexity of life on Earth. While imagination fuels creativity, scientific literacy grounds us in reality. By understanding the distinct characteristics of animals and fungi, we can better appreciate their roles in ecosystems and work toward their preservation. The next time you encounter a bat or a mushroom, marvel at their uniqueness—not as potential hybrids, but as remarkable examples of nature’s ingenuity.

Understanding the Risks: Can You Have a Bad Trip on Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, bats and mushrooms are entirely different organisms. Bats are mammals, while mushrooms are fungi, and there is no biological process that allows one to transform into the other.

There is no scientific method or technology that can convert bats into mushrooms. They belong to different kingdoms of life (Animalia and Fungi) and have fundamentally distinct structures and functions.

Bats and mushrooms share very few similarities. They have different cellular structures, life cycles, and ecological roles, making any transformation between the two impossible.

There are no widely known myths or legends about bats transforming into mushrooms. Such a concept does not exist in folklore or cultural narratives.