The concept of cloning mushrooms has gained significant interest among mycologists and hobbyists alike, as it offers a precise and efficient method to replicate specific fungal strains with desirable traits. Unlike traditional cultivation methods that rely on spores, which can produce genetically diverse offspring, cloning allows for the exact duplication of a parent mushroom, preserving its unique characteristics such as flavor, potency, or growth rate. This technique typically involves taking a tissue sample from a healthy mushroom and cultivating it in a sterile environment to encourage mycelial growth, ensuring the new organism is genetically identical to the original. As interest in mushrooms grows for culinary, medicinal, and ecological purposes, the ability to clone them presents exciting possibilities for both scientific research and practical applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cloning Possibility | Yes, mushrooms can be cloned through tissue culture or spore isolation methods. |

| Common Methods | Tissue culture (using mycelium), spore cloning, and agar-based techniques. |

| Success Rate | High, especially with tissue culture and agar methods. |

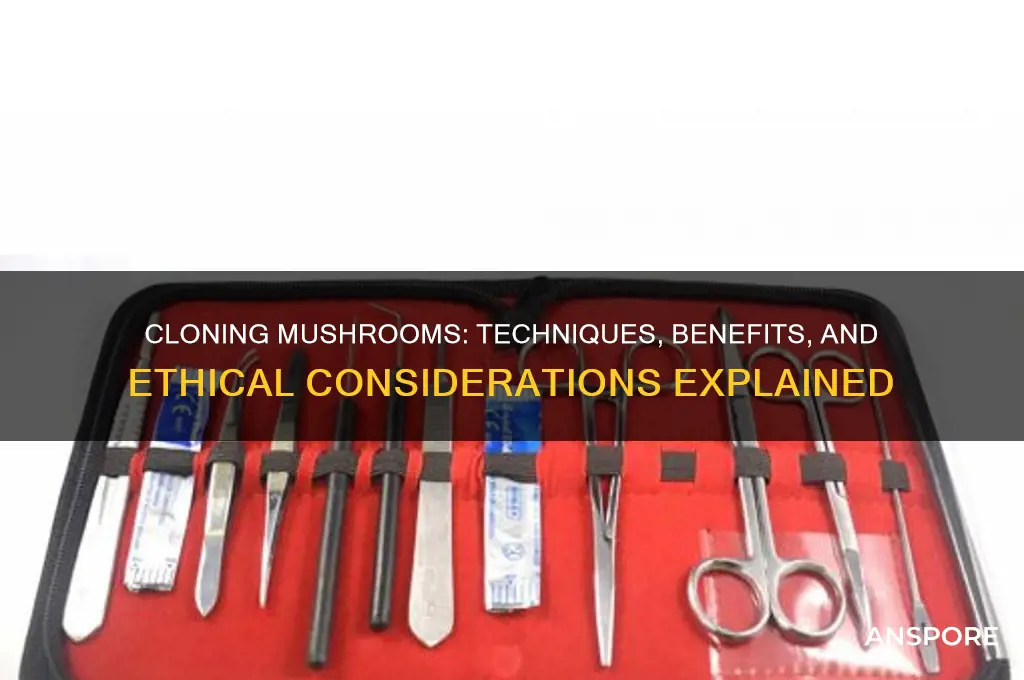

| Required Materials | Sterile agar plates, scalpel, alcohol, petri dishes, and growth medium. |

| Time Frame | 2-6 weeks for visible mycelium growth, depending on species and method. |

| Species Suitability | Most mushroom species can be cloned, including oyster, shiitake, and lion's mane. |

| Advantages | Preserves genetic traits, ensures consistency in cultivation, and avoids contamination. |

| Challenges | Requires sterile conditions, risk of contamination, and species-specific techniques. |

| Cost | Low to moderate, depending on equipment and materials. |

| Legal Considerations | Generally legal, but check local regulations for specific mushroom species. |

| Applications | Commercial cultivation, research, and hobbyist mushroom growing. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Tissue Culture Techniques: Methods for cloning mushrooms using small tissue samples in sterile conditions

- Spore Isolation Process: Collecting and germinating spores to create genetically identical mushroom clones

- Grafting Mushrooms: Joining mushroom mycelium to a compatible host for cloning purposes

- Liquid Culture Cloning: Growing mycelium in nutrient-rich liquid to propagate mushroom clones

- Ethical and Legal Issues: Considerations around mushroom cloning, including patents and biodiversity concerns

Tissue Culture Techniques: Methods for cloning mushrooms using small tissue samples in sterile conditions

Mushroom cloning through tissue culture techniques offers a precise, controlled method for propagating fungi with desirable traits. Unlike traditional spore-based methods, tissue culture relies on small samples of living mushroom tissue, which are cultivated in sterile conditions to produce genetically identical offspring. This approach ensures consistency in traits like yield, potency, or flavor, making it invaluable for both commercial growers and researchers.

The process begins with selecting a healthy, disease-free mushroom as the donor. A small piece of tissue, often from the gill or mycelium, is excised using sterile tools to prevent contamination. This sample is then placed in a nutrient-rich medium, typically agar-based, supplemented with carbohydrates, vitamins, and growth regulators. The medium’s pH is critical, usually maintained between 5.5 and 6.0, to support optimal fungal growth. Sterility is paramount; all equipment and materials must be sterilized, often via autoclaving, to eliminate competing microorganisms.

Once the tissue sample is inoculated, it is incubated in a controlled environment with temperatures ranging from 22°C to 28°C and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Over 2–4 weeks, the tissue proliferates, forming a network of mycelium. This mycelium can then be subcultured onto fresh medium or transferred to a substrate like grain or sawdust for fruiting. Careful monitoring for contamination is essential, as even minor impurities can derail the process.

While tissue culture is highly effective, it requires precision and patience. Contamination risks are significant, and the technique demands a basic understanding of sterile laboratory practices. However, for those seeking to replicate specific mushroom strains with fidelity, tissue culture is unparalleled. It bridges the gap between traditional farming and modern biotechnology, offering a scalable, reliable method for cloning mushrooms with desired characteristics.

Mushroom Farming in Wisconsin: Opportunities, Challenges, and Getting Started

You may want to see also

Spore Isolation Process: Collecting and germinating spores to create genetically identical mushroom clones

Mushroom cloning through spore isolation is a precise art, blending microbiology with horticulture to produce genetically identical fungi. Unlike vegetative cloning, which replicates mushrooms from tissue cuttings, spore isolation begins with the microscopic reproductive units released by mature mushroom caps. Each spore carries a unique genetic blueprint, but when cultivated under controlled conditions, it can grow into a mycelium network identical to its parent. This method is favored by mycologists and cultivators seeking consistency in traits like yield, flavor, or medicinal compounds.

The first step in spore isolation is collection, a process that demands sterility to prevent contamination. Start by selecting a mature mushroom with an open cap, ensuring it’s free from disease or pests. Place a clean glass or plastic container over the cap, allowing spores to fall onto a sterile surface like a petri dish lined with agar. Alternatively, use a spore print—a technique where the cap is placed gills-down on foil or paper overnight. The resulting spore deposit can be scraped into a sterile solution, such as distilled water with a few drops of hydrogen peroxide to inhibit bacteria. Aim for a concentration of 1–2 drops of spore solution per milliliter of liquid to avoid overcrowding during germination.

Germination follows collection, requiring a nutrient-rich medium like potato dextrose agar (PDA) or malt extract agar (MEA). Sterilize the agar by autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, then cool it to 50°C before pouring into petri dishes. Once solidified, introduce the spore solution using a sterile technique, such as flaming the inoculation loop and adding 1–2 drops per dish. Incubate at 22–25°C in darkness for 7–14 days, monitoring for mycelial growth. Successful colonies will appear as white, thread-like structures, ready for transfer to bulk substrate for fruiting.

While spore isolation offers genetic consistency, it’s not without challenges. Contamination from bacteria, mold, or competing fungi is a constant threat, requiring meticulous sterilization and aseptic technique. Additionally, spores from some species germinate slowly or unpredictably, demanding patience and experimentation. For beginners, starting with resilient species like *Psathyrella* or *Psilocybe* can increase success rates. Advanced cultivators may use laminar flow hoods or glove boxes to maintain sterile conditions, though DIY setups with alcohol-sterilized workspaces can suffice for small-scale projects.

The takeaway is that spore isolation is a powerful tool for mushroom cloning, enabling cultivators to preserve and replicate desirable traits. It bridges the gap between wild foraging and controlled cultivation, offering a deeper understanding of fungal biology. With practice, even hobbyists can master this technique, unlocking the potential to grow genetically identical mushrooms tailored to culinary, medicinal, or ecological purposes. Whether for research or personal use, the process transforms spores from invisible seeds into tangible, thriving fungi.

Mushrooms and Aggression: Unraveling the Myth of Violent Fungal Effects

You may want to see also

Grafting Mushrooms: Joining mushroom mycelium to a compatible host for cloning purposes

Mushroom grafting, a technique borrowed from horticulture, involves fusing the mycelium of one mushroom species with a compatible host—often another mushroom or a woody substrate—to create a stable, clonable organism. Unlike traditional cloning methods like tissue culture or spore isolation, grafting leverages the mycelium’s ability to merge with foreign tissue, forming a chimeric entity that retains genetic traits of both parties. This method is particularly useful for preserving rare or high-yield strains, as it bypasses the genetic variability introduced by spore reproduction. For instance, oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) mycelium has been successfully grafted onto shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) logs, combining growth rates of the former with the flavor profile of the latter.

To graft mushrooms, start by sterilizing both the donor mycelium and the host substrate to prevent contamination. A common technique involves making a small incision in the host (e.g., a hardwood log or another mushroom’s mycelial mat) and inserting a mycelium plug or fragment into the wound. The key is to ensure compatibility—species within the same genus, such as *Ganoderma* or *Trametes*, often graft more readily due to shared biochemical pathways. Maintain a humid, sterile environment (around 70-75°F and 60-80% humidity) for 2-4 weeks to allow the mycelia to fuse. Success is indicated by uniform growth and the absence of competing fungi.

While grafting offers precision in cloning, it’s not without challenges. Incompatibility between species can lead to rejection, where the host’s immune response kills the foreign mycelium. Contamination by bacteria or mold is another risk, especially if sterilization protocols are lax. For beginners, start with closely related species and use pre-sterilized substrates to minimize variables. Advanced growers might experiment with intergeneric grafts, though these require meticulous technique and often yield lower success rates.

Comparatively, grafting stands out for its ability to combine desirable traits from different strains, something spore cloning cannot achieve. For example, a graft between a cold-tolerant and a high-yield strain could produce a hybrid suited for cooler climates. However, it’s more labor-intensive and requires a deeper understanding of mycological compatibility. In contrast, spore cloning is simpler but lacks control over genetic outcomes. Grafting is thus a niche but powerful tool for mycologists and cultivators aiming to innovate in mushroom breeding.

In practice, grafting mushrooms is a delicate art that rewards patience and precision. For hobbyists, it’s an opportunity to experiment with hybridization, while commercial growers can use it to stabilize high-performing strains. Keep detailed records of each graft attempt, noting species, environmental conditions, and outcomes, to refine your technique over time. With practice, grafting can become a cornerstone of your mushroom cloning repertoire, offering a unique way to explore the genetic potential of fungi.

Magic Mushrooms and Mental Health: Unraveling the Risks and Realities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Liquid Culture Cloning: Growing mycelium in nutrient-rich liquid to propagate mushroom clones

Mushroom cloning isn't limited to tissue slicing or spore isolation. Liquid culture cloning offers a fascinating alternative, leveraging the mycelium's natural propensity to thrive in nutrient-rich environments. This method involves cultivating mycelium in a liquid medium, creating a suspension teeming with fungal cells ready for inoculation. Think of it as a mushroom "starter culture," similar to yogurt or sourdough, but for fungi.

Liquid culture cloning begins with a sterile environment. Autoclaving your chosen liquid medium (often a mixture of water, sugar, and vitamins) is crucial to eliminate competing microorganisms. Once cooled, introduce a small piece of healthy mycelium from your desired mushroom strain. This fragment acts as the seed, rapidly multiplying within the nutrient-rich broth. Over time, the mycelium will colonize the liquid, resulting in a cloudy, opaque suspension. This liquid culture, now brimming with fungal cells, becomes your cloning tool.

The beauty of liquid culture lies in its versatility. A single batch can be used to inoculate multiple substrates, from agar plates for further isolation to grain spawn for large-scale mushroom production. This efficiency makes it a favorite among mycologists and hobbyists alike. However, precision is key. Maintaining sterility throughout the process is paramount, as contamination can quickly derail your efforts.

Utilizing liquid culture cloning requires attention to detail. Specific nutrient ratios and pH levels within the liquid medium are essential for optimal mycelial growth. Additionally, factors like temperature and oxygenation play crucial roles in the success of your culture. With careful attention to these parameters, liquid culture cloning unlocks a powerful tool for propagating mushroom clones with remarkable consistency and efficiency.

Planting in Mushroom Compost: Benefits, Tips, and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Ethical and Legal Issues: Considerations around mushroom cloning, including patents and biodiversity concerns

Mushroom cloning, while scientifically feasible, raises significant ethical and legal questions that extend beyond the lab bench. One pressing issue is the potential for patenting cloned mushroom strains, which could grant exclusive rights to corporations or individuals, limiting access for small-scale cultivators and indigenous communities who have traditionally relied on these fungi. For instance, the patenting of the *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake) mushroom in the 1980s sparked debates over biopiracy, as this species had been cultivated in Asia for centuries. Such patents can stifle innovation and exploit biodiversity, turning a communal resource into a privatized commodity.

From a biodiversity perspective, cloning mushrooms at scale could inadvertently reduce genetic diversity if monocultures dominate the market. Wild mushroom populations, already under threat from habitat loss and climate change, could face further pressure if cloned varieties outcompete native strains. Consider the case of the *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom), which accounts for over 30% of global mushroom production. Over-reliance on a single cloned strain could make the entire industry vulnerable to diseases or environmental shifts, echoing the risks seen in monoculture agriculture.

Legally, the regulatory landscape for mushroom cloning is fragmented and often unclear. In the United States, the Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has granted patents for genetically modified mushrooms, but the criteria for patenting cloned (non-GMO) strains remain ambiguous. In contrast, the European Union’s Directive 98/44/EC allows patents on biological inventions, including fungi, but excludes plant and animal varieties. This disparity creates a global patchwork of rules, complicating international trade and collaboration. For cultivators, navigating these regulations can be costly and time-consuming, favoring large corporations over smaller operations.

Ethically, the question of consent looms large, particularly when cloning mushrooms from indigenous or culturally significant species. Many indigenous communities view mushrooms as sacred or medicinal, and their commercialization without proper acknowledgment or benefit-sharing raises concerns of cultural appropriation. For example, the *Psilocybe* genus, used in traditional rituals, has been cloned for both therapeutic and recreational purposes, often without involving the communities that hold this knowledge. Establishing frameworks for equitable benefit-sharing, such as those outlined in the Nagoya Protocol, could help address these grievances.

In practical terms, cultivators and researchers must balance innovation with responsibility. Steps include conducting thorough biodiversity impact assessments before scaling up cloning operations, engaging with local communities to ensure ethical sourcing, and advocating for clearer, more equitable patent laws. For instance, open-source platforms like the Open Source Mycology initiative promote collaborative research while safeguarding against over-commercialization. By prioritizing biodiversity and inclusivity, the field of mushroom cloning can advance without compromising ethical or ecological integrity.

Can You Eat Golden Oyster Mushrooms? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can clone mushrooms at home using tissue culture or agar techniques. This involves taking a small piece of mushroom tissue (e.g., from the cap or stem) and growing it in a sterile environment to produce mycelium, which can then be transferred to a substrate for fruiting.

No, cloning mushrooms involves taking a sample of living mycelium or tissue from an existing mushroom to create an exact genetic copy. Growing from spores, on the other hand, involves sexual reproduction, which can result in genetic variation among the offspring.

Cloning mushrooms ensures genetic consistency, meaning the cloned mushrooms will have the same traits (e.g., size, flavor, yield) as the parent mushroom. It also allows you to preserve rare or desirable strains and can be faster than starting from spores.

Basic equipment includes a sterile workspace (e.g., a still air box or laminar flow hood), agar plates or liquid culture media, scalpel or blade, alcohol for sterilization, and containers for growing the mycelium. Advanced setups may include pressure cookers for sterilizing substrates.

![Boomer Shroomer Inflatable Monotub Kit, Mushroom Growing Kit Includes a Drain Port, Plugs & Filters, Removeable Liner [Patent No: US 11,871,706 B2]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61uwAyfkpfL._AC_UL320_.jpg)