The question of whether you can eat maggots found in mushrooms is both intriguing and unsettling, blending curiosity about survival food sources with concerns about safety and hygiene. Maggots, the larval stage of flies, occasionally infest mushrooms, particularly those left in damp or decaying environments. While some cultures historically consumed insects and larvae as part of their diet, the safety of eating maggots from mushrooms depends on factors like the mushroom species, the maggot type, and potential toxins or pathogens present. Generally, consuming maggots from wild mushrooms is not recommended due to risks of contamination or poisoning, though certain controlled environments might produce edible larvae. This topic highlights the intersection of entomophagy (eating insects), mycology (the study of fungi), and food safety, inviting exploration of both cultural practices and scientific considerations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility of Maggots in Mushrooms | Generally not recommended |

| Health Risks | Potential bacterial infections, parasites, or toxins |

| Nutritional Value | Low; maggots may contain protein but are not a significant source of nutrients |

| Common Mushroom Types Affected | Cultivated mushrooms (e.g., button, shiitake) and wild mushrooms |

| Prevention Methods | Proper storage, refrigeration, and inspection of mushrooms before consumption |

| Culinary Use | Not a recognized culinary practice; considered unappetizing and unsafe |

| Expert Opinion | Most food safety experts advise against consuming maggots in mushrooms |

| Legal Status | Not regulated specifically, but falls under general food safety guidelines |

| Cultural Practices | Not a traditional or accepted practice in any cuisine |

| Alternative Solutions | Discard infested mushrooms and practice better food storage habits |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Safety Concerns: Are maggots in mushrooms safe to eat, or do they pose health risks

- Edible Mushroom Types: Which mushroom species commonly host maggots, and are they edible

- Maggot Identification: How to distinguish harmful maggots from harmless ones in mushrooms

- Prevention Methods: Tips to avoid maggots infesting mushrooms during storage or foraging

- Culinary Uses: Do some cultures intentionally use maggot-infested mushrooms in traditional dishes

Safety Concerns: Are maggots in mushrooms safe to eat, or do they pose health risks?

Maggots in mushrooms, while unappetizing to many, are not inherently toxic. These larvae, typically from flies, feed on decaying organic matter, including mushrooms. If the mushroom itself is safe to eat, the maggots consuming it are unlikely to render it poisonous. However, their presence raises legitimate safety concerns that go beyond mere squeamishness.

Understanding the risks requires considering the maggots' role as potential carriers of bacteria and parasites.

From a health perspective, the primary danger lies in what maggots might bring to the table, quite literally. Flies, whose larvae become maggots, are known to frequent unsanitary environments. This means maggots can harbor harmful bacteria like Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, which can cause foodborne illnesses. While cooking mushrooms thoroughly (to an internal temperature of 165°F or 74°C) can kill these bacteria, it's crucial to remember that maggots themselves are not a food source and offer no nutritional benefit.

Consuming them, even accidentally, increases the risk of ingesting these pathogens.

A comparative analysis highlights the difference between intentional entomophagy (insect consumption) and accidental ingestion. In cultures where insects are a dietary staple, careful preparation and sourcing ensure safety. Maggots found in wild mushrooms, however, lack this controlled environment. Their origins are unknown, and the mushrooms they inhabit may have been exposed to contaminants. This lack of control significantly elevates the potential health risks.

For those considering whether to salvage a mushroom infested with maggots, a cautious approach is paramount. Carefully inspect the mushroom, removing any visible larvae and thoroughly washing it. However, if the infestation is severe or the mushroom shows signs of decay beyond the maggots' presence, it's best to discard it entirely. Remember, while maggots themselves may not be poisonous, the risks they carry outweigh any potential benefit.

Can Cats Safely Eat Wild Mushrooms? Risks and Precautions Explained

You may want to see also

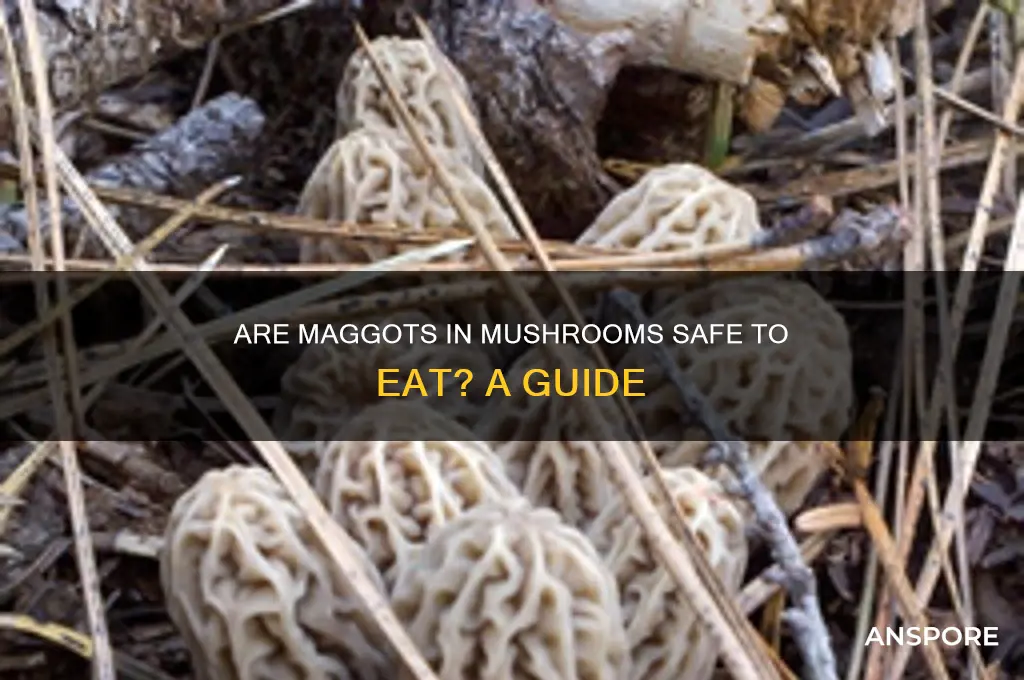

Edible Mushroom Types: Which mushroom species commonly host maggots, and are they edible?

Certain mushroom species, particularly those in the Agaricus genus, are prone to maggot infestation. These larvae, often from flies like the mushroom feeder fly (Lycoriella auripila), are attracted to the fruiting bodies as a nutrient-rich environment for development. While the presence of maggots might deter foragers, it’s crucial to distinguish between species susceptibility and edibility. For instance, the common button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) and its wild counterpart, the horse mushroom (Agaricus arvensis), are frequently affected but remain safe for consumption after proper cleaning. The maggots themselves, though unappetizing, are not toxic if accidentally ingested in small quantities.

From a culinary perspective, the discovery of maggots in mushrooms like the meadow mushroom (Agaricus campestris) or the prince mushroom (Agaricus augustus) should prompt careful inspection rather than immediate discard. To salvage infested mushrooms, submerge them in cold, salted water for 10–15 minutes to expel the larvae. Afterward, thoroughly rinse and inspect the mushrooms before cooking. This method ensures both the removal of maggots and the preservation of the mushroom’s texture and flavor. However, heavily infested specimens are best avoided, as the larvae may compromise the mushroom’s integrity.

A comparative analysis reveals that while maggot-prone mushrooms like Agaricus species are generally edible, other varieties, such as the shaggy mane (Coprinus comatus) or the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), are less susceptible to infestation. This difference highlights the importance of species identification in foraging. For instance, the shaggy mane’s delicate structure and rapid decomposition make it less appealing to fly larvae, whereas the dense flesh of oyster mushrooms deters infestation. Foragers should prioritize learning these distinctions to minimize encounters with maggots while harvesting.

Persuasively, the presence of maggots should not automatically disqualify a mushroom from consumption, provided it belongs to an edible species and is properly prepared. The nutritional value of mushrooms—rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants—far outweighs the minor inconvenience of maggot removal. Moreover, embracing imperfect specimens aligns with sustainable foraging practices, reducing waste and promoting a deeper connection with nature. By adopting practical cleaning techniques and species-specific knowledge, enthusiasts can safely enjoy maggot-prone mushrooms without compromising their culinary experience.

Do Mushrooms Age? Exploring the Lifespan of Fungi

You may want to see also

Maggot Identification: How to distinguish harmful maggots from harmless ones in mushrooms

Mushrooms, with their diverse ecosystems, often host maggots, leaving foragers and cooks to discern which are safe to consume. Not all maggots in mushrooms pose a threat; some are harmless byproducts of the fungus’s life cycle, while others indicate spoilage or toxicity. Identifying the type of maggot is crucial, as misjudgment can lead to illness or unnecessary waste. Here’s how to distinguish between harmful and harmless maggots in mushrooms.

Step 1: Examine the Mushroom Species

Different mushrooms attract specific insects. For instance, *Fly Agaric* (*Amanita muscaria*) often hosts larvae of the yellow-spotted mushroom fly, which are harmless but unappetizing. In contrast, decaying store-bought mushrooms may contain larvae of the common housefly, which can carry pathogens. Knowing the mushroom species narrows down potential maggot types. For example, if you find maggots in *Shiitake* mushrooms, they are likely from the shiitake fly, whose larvae are not harmful but signal overripe fungi.

Step 2: Observe Maggot Appearance and Behavior

Harmless maggots, such as those from mushroom-specific flies, are often small (2–5 mm), translucent, and slow-moving. They feed exclusively on mushroom tissue without causing widespread decay. Harmful maggots, like those from blowflies or fruit flies, are larger (5–10 mm), opaque, and active. They indicate secondary infestation or spoilage, often accompanied by a foul odor or slimy texture in the mushroom. A magnifying glass can help identify fine details, such as mouthparts or segmentation.

Step 3: Assess Mushroom Condition

Maggots in firm, fresh mushrooms with no signs of mold or discoloration are typically harmless. However, if the mushroom is soft, discolored, or emits an off-putting smell, the maggots are likely harmful, as they thrive in decomposing environments. For example, maggots in a *Portobello* mushroom with a firm cap and gills are probably harmless, but those in a soggy, brown *Button* mushroom should be discarded.

Caution: When in Doubt, Throw It Out

While some cultures intentionally consume maggot-infested foods (e.g., *casu marzu* cheese), mushrooms are not traditionally part of this practice. Even harmless maggots can trigger allergic reactions or psychological aversion. If you cannot confidently identify the maggot type, err on the side of caution. Cooking does not always eliminate pathogens, and some toxins may persist.

Practical Tip: Prevention is Key

Store mushrooms in a breathable container (e.g., paper bags) in the refrigerator to reduce moisture and deter flies. Inspect for eggs or larvae before cooking, especially in wild-harvested varieties. Freezing mushrooms for 24–48 hours can kill any larvae, but this may alter texture. For foragers, avoid collecting mushrooms with visible holes or frass (insect waste), as these are signs of infestation.

By combining species knowledge, visual inspection, and condition assessment, you can safely distinguish between maggots that are merely unappealing and those that render mushrooms unsafe. Always prioritize health over curiosity, and when in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely.

Mushroom and Egg Combo: Safe, Nutritious, and Delicious Pairing Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Prevention Methods: Tips to avoid maggots infesting mushrooms during storage or foraging

Maggots in mushrooms are the larvae of flies, particularly the mushroom fly (*Lycoriella auripila*), which lays eggs on or near fungi. These larvae can quickly infest mushrooms, rendering them unappetizing and potentially unsafe to eat. While some cultures consume maggots as a protein source, most foragers and chefs aim to avoid them. Prevention is key, and understanding the fly’s lifecycle is the first step. Mushroom flies are attracted to damp, decaying organic matter, making freshly harvested or improperly stored mushrooms prime targets. By disrupting their breeding environment, you can significantly reduce the risk of infestation.

Foraging Practices: Minimize Exposure in the Field

When foraging, inspect mushrooms carefully before collecting. Avoid specimens with visible fly activity, such as tiny white eggs or larvae. Harvest only healthy, firm mushrooms, as flies are drawn to overripe or damaged fungi. Store foraged mushrooms in breathable containers like paper bags or mesh nets, not plastic, which traps moisture. Clean your tools and hands after handling mushrooms to prevent transferring eggs or larvae between sites. Foraging in dry, well-ventilated areas also reduces the likelihood of encountering mushroom flies, as they thrive in humid environments.

Storage Solutions: Create an Unfavorable Environment

Proper storage is critical to preventing maggot infestations. Refrigerate mushrooms at 34–38°F (1–3°C) to slow fly activity, but note that cold temperatures don’t kill eggs already present. Before storing, brush off soil and debris, as these can harbor fly eggs. For long-term storage, blanch mushrooms in boiling water for 2–3 minutes, then freeze or dehydrate them. Freezing at 0°F (-18°C) for 48 hours ensures any existing larvae are eliminated. Alternatively, dehydrate mushrooms at 125°F (52°C) until completely dry, as flies avoid desiccated environments.

Natural Repellents: Deter Flies Without Chemicals

Incorporate natural deterrents to protect stored mushrooms. Place herbs like lavender, mint, or rosemary near storage areas, as their strong scents repel flies. Diatomaceous earth, a non-toxic powder, can be sprinkled around containers to dehydrate and kill larvae. For outdoor storage, hang sticky traps or use vinegar traps to catch adult flies. Avoid chemical pesticides, as they can contaminate mushrooms and harm beneficial insects. Regularly clean storage areas with a vinegar solution to eliminate eggs and larvae, ensuring a hygienic environment.

Monitoring and Maintenance: Stay Vigilant

Regularly inspect stored mushrooms for signs of infestation, such as small holes or larvae movement. If maggots are detected, discard the affected mushrooms immediately to prevent further spread. Rotate stock frequently, using older mushrooms first. For large quantities, consider storing them in separate batches to isolate any potential infestations. Educate yourself on the appearance of mushroom fly eggs and larvae to catch issues early. By combining these methods, you can enjoy maggot-free mushrooms whether foraging or storing, ensuring both safety and quality.

Marinating Shiitake Mushrooms: Tips, Benefits, and Flavorful Recipes

You may want to see also

Culinary Uses: Do some cultures intentionally use maggot-infested mushrooms in traditional dishes?

While the idea of consuming maggots might be unappetizing to many, certain cultures have indeed embraced the concept of using maggot-infested mushrooms in their traditional cuisine. One notable example is the Sardinian casu martzu, a sheep milk cheese notorious for containing live insect larvae. Although not a mushroom, this cheese sets a precedent for the intentional incorporation of maggots in food. In the context of mushrooms, some foragers and culinary adventurers argue that maggot-infested specimens, when properly prepared, can offer unique flavors and textures. However, this practice is far from mainstream and is often confined to specific regions or niche culinary circles.

From an analytical perspective, the intentional use of maggot-infested mushrooms in traditional dishes raises questions about food safety and cultural perceptions of edibility. Maggots, being the larvae of flies, can carry pathogens and bacteria that pose health risks if not handled correctly. Cultures that incorporate such ingredients often have meticulous preparation methods to mitigate these risks. For instance, some traditions involve thoroughly cooking the mushrooms to eliminate potential contaminants, while others rely on fermentation processes that create an environment hostile to harmful microorganisms. These practices highlight the intersection of culinary innovation and biological caution.

Instructively, if one were to experiment with maggot-infested mushrooms, several precautions must be taken. First, ensure the mushroom species is safe for consumption, as not all mushrooms are edible. Second, inspect the maggots themselves; avoid mushrooms with larvae that appear discolored or emit foul odors, as these could indicate spoilage. Third, cooking methods such as boiling, sautéing, or pickling can reduce the risk of foodborne illnesses. For those curious but hesitant, starting with small quantities and pairing the mushrooms with strong flavors like garlic or herbs can make the experience more palatable.

Comparatively, the use of maggot-infested mushrooms can be likened to other global culinary practices that challenge conventional notions of food. For example, the Scandinavian delicacy surströmming (fermented herring) or the Korean dish hongeo-hoe (fermented skate) both rely on controlled decomposition to achieve their distinctive tastes. Similarly, maggot-infested mushrooms can be seen as a form of natural fermentation, where the larvae break down the mushroom’s tissues, altering its texture and flavor profile. This perspective shifts the focus from revulsion to appreciation of the biological processes at play.

Descriptively, dishes featuring maggot-infested mushrooms often emphasize the contrast between the earthy, umami-rich flavor of the fungi and the subtle crunch or creaminess introduced by the larvae. In some cultures, these mushrooms are served as part of hearty stews or soups, where their unique characteristics blend seamlessly with other ingredients. Others might showcase them in simpler preparations, such as sautéed with butter and herbs, to highlight their distinct qualities. The result is a dish that is both a testament to culinary bravery and a celebration of nature’s unpredictability.

In conclusion, while the intentional use of maggot-infested mushrooms in traditional dishes remains a niche practice, it offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of global culinary traditions. By understanding the cultural, safety, and sensory aspects of this practice, one can approach it with curiosity rather than aversion. Whether viewed as a daring experiment or a cherished tradition, these dishes remind us that the boundaries of edibility are often shaped by context, creativity, and courage.

Can You Eat Dried Mushrooms Without Reconstituting? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is not recommended to eat maggots found in mushrooms, as they may carry bacteria, parasites, or toxins that could be harmful to humans.

Yes, maggots in mushrooms typically indicate that the mushrooms have been infested by flies, which suggests improper storage or handling, leading to potential contamination.

While cooking can kill bacteria and parasites, it’s still risky to consume maggots in mushrooms due to potential toxins or allergens they may carry. It’s best to discard infested mushrooms.