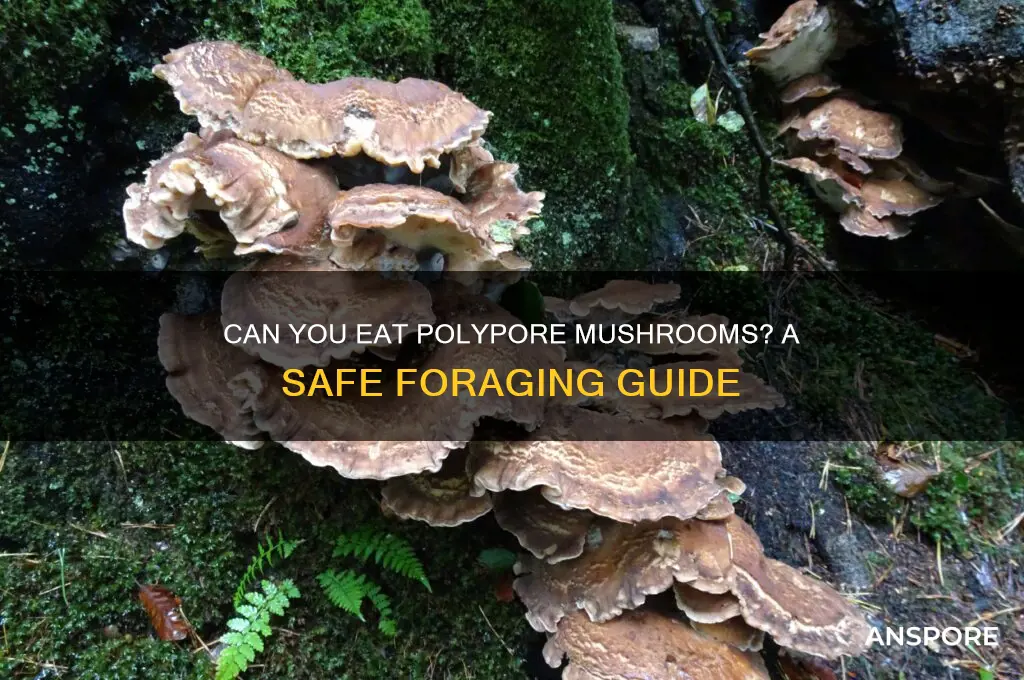

Polypore mushrooms, a diverse group of fungi characterized by their pore-like structures on the underside of the cap, have long intrigued foragers and mycologists alike. While some polypores are prized for their medicinal properties or ecological roles, others are known to be inedible or even toxic. The question of whether you can eat polypore mushrooms depends largely on the specific species, as not all are safe for consumption. Notable edible varieties, such as the chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) and the birch polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*), are enjoyed for their unique textures and flavors, though proper identification is crucial. Conversely, many polypores, like the artist's conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), are tough, bitter, or harmful if ingested. Therefore, thorough research and expert guidance are essential before considering any polypore for culinary use.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Some polypore mushrooms are edible, but many are not. Edible species include Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus), Birch Polypore (Piptoporus betulinus), and Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus). |

| Toxicity | Most polypores are non-toxic but inedible due to their tough, woody texture. A few species may cause gastrointestinal upset if consumed. |

| Texture | Typically tough, leathery, or woody, making them unappealing for consumption in their raw or mature state. |

| Flavor | Edible species like Chicken of the Woods have a mild, chicken-like flavor when cooked properly. |

| Preparation | Edible polypores must be cooked thoroughly to soften their texture. Young, tender specimens are preferred. |

| Nutritional Value | Edible polypores may contain beneficial compounds like beta-glucans, antioxidants, and vitamins, but their nutritional value is generally low due to their fibrous nature. |

| Identification | Proper identification is crucial, as some polypores resemble toxic or inedible species. Consult a field guide or expert. |

| Common Uses | Edible species are used in cooking, while others have medicinal or decorative purposes. |

| Habitat | Found on trees or wood, often in forests. Edible species are typically harvested in the wild, not cultivated. |

| Season | Availability varies by species; some are found in spring or summer, while others persist year-round. |

| Conservation | Harvest sustainably to avoid damaging ecosystems, as polypores play a role in wood decomposition. |

Explore related products

$19.2 $24.95

What You'll Learn

Identifying edible polypore species safely

Polypore mushrooms, with their distinctive shelf-like or bracket-shaped caps, are a fascinating group of fungi that grow on trees or wood. While many are inedible or too tough to consume, some species are not only edible but also prized for their unique flavors and textures. However, identifying edible polypores safely requires careful observation and knowledge to avoid toxic look-alikes. Here’s how to approach this task with confidence.

Step 1: Learn Key Characteristics

Start by familiarizing yourself with the defining features of edible polypores. Look for species like *Laetiporus sulphureus* (Chicken of the Woods), known for its bright orange-yellow fan-like clusters and sulfur-colored pores. Another example is *Grifola frondosa* (Maitake), which grows in layered, wavy clusters with a grayish-brown hue. Always note the pore structure, color, and texture of the underside, as these are critical identifiers. For instance, edible polypores typically have soft, pliable flesh when young, while inedible ones may be woody or brittle.

Caution: Avoid Common Mistakes

One of the biggest risks in identifying polypores is confusing them with toxic species. For example, *Ganoderma applanatum* (Artist’s Conk) resembles *Laetiporus* in shape but has a white pore surface that turns brown when bruised, making it inedible. Similarly, *Fomes fomentarius* (Tinder Conk) has a tough, fibrous texture unsuitable for consumption. Always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult an expert if unsure, as misidentification can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress or worse.

Practical Tips for Safe Foraging

When foraging, harvest only young, fresh specimens, as older polypores become tough and unpalatable. Use a knife to cut the mushroom at its base, leaving enough behind to allow regrowth. Avoid collecting near roadsides or industrial areas due to potential contamination. Once harvested, cook polypores thoroughly, as raw consumption can cause digestive issues. For *Laetiporus*, simmer in soups or sauté until tender; for *Grifola*, roast or grill to enhance its earthy flavor. Always test a small portion first to ensure no adverse reactions.

Can You Eat Morrell Mushrooms Raw? Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Health benefits and nutritional value of polypores

Polypores, a diverse group of bracket fungi, have long been revered in traditional medicine, but their nutritional and health benefits are only recently gaining attention in modern wellness circles. Among the most studied species are *Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor)* and *Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum)*, both of which contain bioactive compounds like polysaccharides, terpenoids, and antioxidants. These compounds are linked to immune modulation, anti-inflammatory effects, and potential anticancer properties. For instance, *Turkey Tail* is FDA-approved for clinical trials in cancer research due to its polysaccharide-K (PSK), which enhances immune function in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

To harness these benefits, preparation matters. Polypores are tough and woody, making them unsuitable for direct consumption. Instead, they are typically consumed as teas, tinctures, or supplements. A standard dosage for *Turkey Tail* extract is 1–3 grams daily, while *Reishi* is often taken in 1.5–9 gram doses, depending on the form. For tea, simmer 2–3 slices of dried polypore in hot water for 20–30 minutes to extract beneficial compounds. Caution: Always source polypores from reputable suppliers to avoid contamination or misidentification, as some species can be toxic.

Comparatively, polypores stand out from other medicinal mushrooms like *Chaga* or *Lion’s Mane* due to their unique polysaccharide profiles. While *Lion’s Mane* is prized for cognitive benefits, polypores excel in immune support and stress reduction. For example, *Reishi* contains triterpenes that promote relaxation and improve sleep quality, making it a popular choice for those managing anxiety or insomnia. However, their effects are gradual, requiring consistent use over weeks to notice benefits.

Practical integration into daily routines is key. Add *Turkey Tail* powder to smoothies or soups for a subtle earthy flavor, or incorporate *Reishi* tincture into evening tea for better sleep. For older adults or those with compromised immunity, polypores can be a valuable addition to a holistic health regimen, but consult a healthcare provider to avoid interactions with medications. While not a panacea, polypores offer a natural, evidence-backed way to support overall well-being.

Drying Nemeko Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Guide for Preservation and Flavor

You may want to see also

Proper preparation and cooking methods for polypores

Polypores, often bracket-like fungi growing on trees, are not typically considered choice edibles due to their tough, woody texture. However, some species, like the birch polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*) or the artist’s conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), are edible when young and properly prepared. The key to making polypores palatable lies in breaking down their fibrous structure, which requires specific techniques beyond basic sautéing or boiling.

One effective method is prolonged simmering or pressure cooking. For example, slicing young, tender polypores into thin strips and simmering them in a broth for 1–2 hours can soften the tissue, making it chewable. Adding acidic ingredients like lemon juice or vinegar during cooking can further help break down the chitinous cell walls. Alternatively, a pressure cooker reduces this time to 30–45 minutes, yielding a texture suitable for stews or soups. The resulting liquid can be strained and used as a flavorful base, rich in umami compounds.

For those seeking a more hands-off approach, drying and powdering polypores is a practical alternative. Dried polypores can be ground into a fine powder and used as a nutritional supplement or flavor enhancer. This method preserves their medicinal properties, such as immune-boosting beta-glucans, without requiring extensive cooking. A teaspoon of polypore powder can be stirred into teas, smoothies, or soups, offering a subtle earthy flavor and potential health benefits.

It’s crucial to exercise caution, as not all polypores are safe to consume. Always identify the species with certainty, avoiding toxic look-alikes like the varnish shelf (*Ganoderma tsugae*). Young specimens are ideal, as older ones become too tough even for prolonged cooking. Proper preparation transforms polypores from inedible curiosities into functional ingredients, but respect for their limitations is paramount.

Beef Stock in Mushroom Risotto: A Flavorful Twist or Miss?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.5 $22.95

$18.14 $24.99

Potential risks and toxic polypore varieties to avoid

Not all polypores are created equal, and some can be downright dangerous. While many species are edible and even prized for their culinary and medicinal properties, others contain toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, organ damage, or worse. Identifying these toxic varieties is crucial for anyone foraging or experimenting with polypores.

For instance, the Funnel Chanterelle (Craterellus fallax) is sometimes mistaken for edible chanterelles due to its similar appearance, but it can cause severe vomiting and diarrhea. Similarly, the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius) resembles the edible Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) but contains toxins that lead to intense gastrointestinal symptoms. Misidentification is a common pitfall, as these toxic species often share colors, textures, or growth habits with their edible counterparts. Always cross-reference multiple field guides and consult experts when in doubt.

Toxic polypores don’t always announce their danger with vivid colors or foul odors. Some, like the Poison Polyporus (Polyporus arcularius), appear innocuous but contain compounds that can cause allergic reactions or mild poisoning. Others, such as the Velvet-Foot (Flammulina velutipes), are generally edible but can accumulate toxins when grown near polluted areas. This highlights the importance of not only identifying the species but also considering its environment. Foraging near roadsides, industrial sites, or agricultural fields increases the risk of exposure to heavy metals or pesticides, which mushrooms readily absorb. Always harvest from clean, unpolluted areas and test a small portion before consuming a full meal.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to toxic polypores due to their smaller body mass and less developed immune systems. Even species considered mildly toxic, like the Dyer’s Polypore (Phaeolus schweinitzii), can cause severe reactions in these groups. Symptoms of poisoning often include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and in extreme cases, liver or kidney damage. If ingestion is suspected, seek medical attention immediately and bring a sample of the mushroom for identification. Prevention is key: educate children about the dangers of wild mushrooms and keep pets on a leash during outdoor activities.

To minimize risks, follow these practical steps: 1) Learn the key identifiers of toxic polypores, such as spore color, pore structure, and habitat. 2) Use a spore print test to distinguish between similar-looking species. 3) Cook all polypores thoroughly, as heat can break down some toxins. 4) Start with a small taste and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions. 5) Document your findings with photos and notes to improve future identification. Remember, foraging should be a mindful practice, not a gamble. The reward of a delicious meal is never worth the risk of poisoning.

Can You Eat Oyster Mushroom Stems? A Culinary Guide

You may want to see also

Foraging tips for finding edible polypores in the wild

Not all polypores are created equal, and while some are prized for their culinary and medicinal properties, others can be toxic or simply unpalatable. Foraging for edible polypores requires a keen eye, patience, and a solid understanding of their characteristics. Start by familiarizing yourself with the most commonly edible species, such as the birch polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*), known for its anti-inflammatory properties, and the lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), celebrated for its seafood-like texture and cognitive benefits. These species are not only safe to eat but also offer unique flavors and health advantages.

To locate polypores in the wild, focus on their preferred habitats. Polypores are primarily wood-decay fungi, so they thrive on dead or dying trees, particularly hardwoods like oak, beech, and birch. Walk through mature forests during late summer and fall, when fruiting bodies are most abundant. Look for bracket-like structures growing directly on tree trunks or branches. The birch polypore, for instance, is often found on birch trees, while lion’s mane prefers hardwoods and appears as cascading white spines. Bring a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to cross-reference your findings, ensuring accuracy.

Once you’ve identified a potential candidate, inspect it closely. Edible polypores typically have a tough, leathery texture when mature, but younger specimens can be tender and more suitable for cooking. Avoid any with signs of decay, mold, or insect damage. For example, turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*), while not typically eaten due to its toughness, is easily recognizable by its colorful, banded caps and can serve as a landmark for nearby edible species. Always cut or twist the polypore from the tree rather than pulling it, as this preserves the mycelium and allows for future growth.

Foraging ethically is as important as foraging safely. Never harvest more than you need, and leave behind enough specimens to ensure the species’ survival. Polypores play a crucial role in forest ecosystems by decomposing wood and recycling nutrients. Additionally, avoid collecting near roadsides or polluted areas, as mushrooms can absorb toxins. If you’re new to foraging, consider joining a local mycological society or going on guided foraging trips to build your skills and confidence.

Finally, preparation is key to enjoying edible polypores. Tougher species like the birch polypore are best used in teas or tinctures to extract their medicinal compounds, while lion’s mane can be sautéed, baked, or battered and fried to highlight its crab-like flavor. Always cook polypores thoroughly, as raw consumption can be difficult to digest. Experiment with recipes, but start with small portions to test for any allergic reactions. With the right knowledge and respect for nature, foraging for edible polypores can be a rewarding and sustainable way to connect with the wild.

Do Magic Mushrooms Lose Potency Over Time? Key Factors Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some polypore mushrooms are edible, but not all. Common edible species include the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) and the Birch Polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*). Always identify with certainty before consuming.

Most polypore mushrooms are tough and woody, making them unsuitable for raw consumption. They are typically cooked or prepared as teas to make them palatable and digestible.

Edible polypore mushrooms, like Reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*) and Turkey Tail (*Trametes versicolor*), are known for their immune-boosting and anti-inflammatory properties. They are often used in traditional medicine and as dietary supplements.