Eating slimy mushrooms is a topic that raises significant concerns due to potential health risks. While some mushrooms develop a slimy texture due to age, moisture, or decomposition, this slime can indicate bacterial growth or spoilage, making them unsafe to consume. Additionally, certain wild mushrooms naturally have a slimy coating, but many of these are toxic or inedible. It’s crucial to accurately identify mushrooms and assess their freshness before consumption. When in doubt, it’s best to avoid slimy mushrooms altogether, as the risks of poisoning or foodborne illness far outweigh any potential benefits. Always consult a knowledgeable source or expert if unsure.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Generally not recommended; slimy mushrooms are often a sign of decay or bacterial growth, which can be harmful. |

| Common Types | Mushrooms like button, cremini, or portobello may develop slime when spoiled, but wild mushrooms with slime are often toxic. |

| Slime Cause | Bacterial or fungal overgrowth, excessive moisture, or decomposition. |

| Health Risks | Potential food poisoning, gastrointestinal issues, or allergic reactions. |

| Safe Consumption | Only if the slime is minimal and the mushroom is otherwise fresh and properly stored. |

| Storage Tips | Store mushrooms in paper bags or loosely wrapped in a damp cloth in the fridge; avoid plastic bags. |

| Shelf Life | Fresh mushrooms last 5-7 days; slime indicates spoilage. |

| Cooking Advice | Do not cook or consume slimy mushrooms; discard immediately. |

| Alternative Uses | Not suitable for consumption, even in cooked forms. |

| Expert Opinion | Mycologists and food safety experts advise against eating any slimy mushrooms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying safe, edible mushrooms with slime

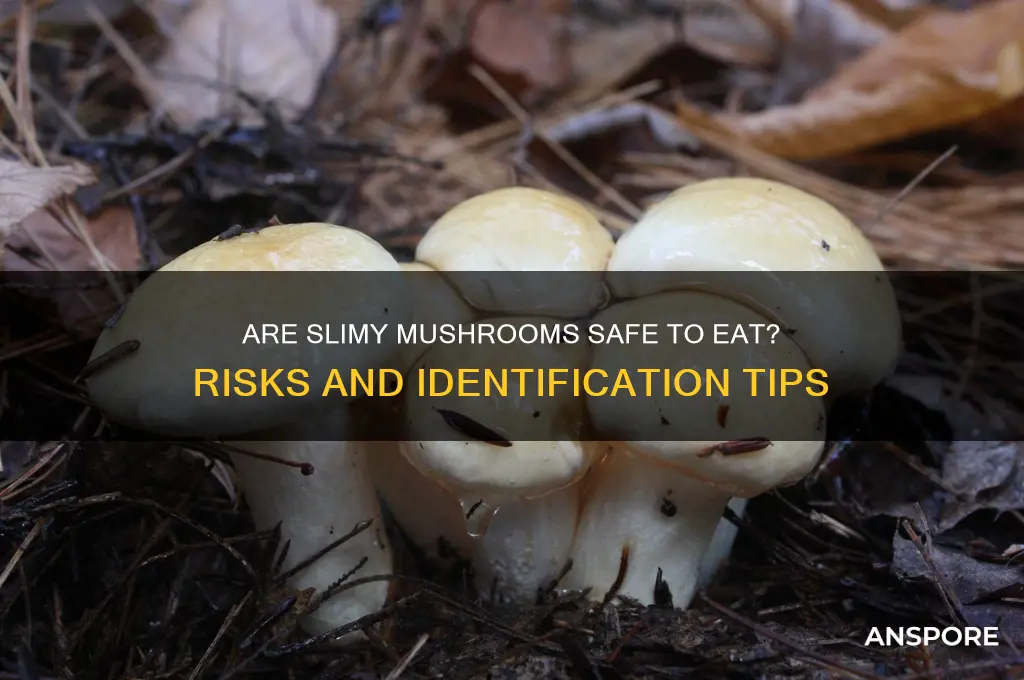

Slime on mushrooms often triggers alarm, but not all slimy mushrooms are toxic. The key lies in understanding the source of the slime and the mushroom’s overall characteristics. For instance, the *Amethyst Deceiver* (*Laccaria amethystina*) naturally has a slimy cap when young, yet it’s edible and prized in European cuisine. Similarly, the *Slippery Jack* (*Suillus luteus*) has a slimy cap but is safe to eat after removing the skin. Identifying these species requires observing their habitat, spore color, and gill structure, not just the slime.

Analyzing slime composition can provide clues to edibility. Slime caused by bacterial growth or decay is a red flag, often accompanied by a foul odor or discolored flesh. In contrast, naturally occurring slime, like that on *Coprinus comatus* (Shaggy Mane), is harmless and disappears as the mushroom matures. A practical tip: if the slime is part of the mushroom’s natural texture and the mushroom is otherwise firm and free of mold, it’s worth further investigation. Always cross-reference with a reliable field guide or expert.

Foraging safely requires a step-by-step approach. First, note the mushroom’s environment—edible slimy mushrooms often grow in symbiotic relationships with trees, like *Suillus* species near pines. Second, examine the slime’s consistency and color; clear, gelatinous slime is more likely natural than cloudy or discolored slime. Third, check for other identifying features: does it have a ring, spores, or a specific cap shape? For example, the *Oyster Mushroom* (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) can appear slimy in humid conditions but is easily identified by its shell-like cap and lack of gills.

Caution is paramount. Never taste or touch a mushroom to test its safety, as toxins can be absorbed through the skin. Instead, carry a knife and gloves while foraging. If unsure, avoid consumption—some toxic mushrooms, like the *Conocybe filaris*, can resemble edible slimy species. For beginners, focus on learning 2–3 common edible slimy mushrooms in your region before expanding your repertoire. Apps like iNaturalist can aid in identification, but always verify with a mycologist.

In conclusion, slime alone isn’t a definitive indicator of toxicity. By combining habitat analysis, physical characteristics, and slime type, foragers can safely identify edible mushrooms like the *Slippery Jack* or *Amethyst Deceiver*. Always prioritize caution, use reliable resources, and when in doubt, leave it out. With practice, distinguishing safe, slimy mushrooms becomes an accessible skill, opening up a unique culinary world.

Selling Mushrooms from Home in Ohio: Legalities and Opportunities

You may want to see also

Risks of consuming slimy wild mushrooms

Slime on wild mushrooms often signals bacterial growth or decay, both of which can render the fungus unsafe to eat. While not all slimy mushrooms are toxic, the slime itself is a red flag. Bacteria thrive in moist environments, and mushrooms left in humid conditions or past their prime become breeding grounds for harmful microbes. Consuming these can lead to foodborne illnesses like salmonella or E. coli, causing symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Even if the mushroom species is edible, the slime indicates it’s no longer fit for consumption.

Analyzing the risks further, slime can also mask underlying issues. Some mushrooms naturally develop a slimy layer as they age, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they’re poisonous. However, the slime can obscure dangerous characteristics, such as mold or the presence of toxic look-alikes. For instance, the deadly Amanita species can sometimes appear deceptively similar to edible varieties when covered in slime. Without proper identification, even experienced foragers can mistake a toxic mushroom for a safe one, leading to severe poisoning or even death.

To minimize risks, follow these practical steps: First, avoid harvesting or consuming any wild mushroom with visible slime. Second, inspect mushrooms closely in good lighting to ensure no slime is present, especially in crevices or under the cap. Third, store harvested mushrooms in breathable containers (like paper bags) to prevent moisture buildup, which can lead to slime formation. If you’re unsure about a mushroom’s condition, err on the side of caution and discard it. Remember, no meal is worth risking your health.

Comparatively, store-bought mushrooms are less likely to pose these risks due to controlled growing conditions and quality checks. However, even cultivated mushrooms can develop slime if improperly stored. Always refrigerate them in paper bags or loosely wrapped in paper towels to absorb excess moisture. If you notice slime, discard the mushroom immediately—cooking won’t eliminate bacterial toxins or neutralize potential poisons. Wild foragers, in particular, must remain vigilant, as the risks are exponentially higher without the safeguards of commercial cultivation.

Finally, consider the long-term health implications. Repeated exposure to bacteria from slimy mushrooms can weaken the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections. For children, the elderly, or those with compromised immune systems, the risks are even greater. Educate yourself on mushroom identification and always consult a reliable guide or expert when in doubt. While foraging can be rewarding, it’s a responsibility that demands respect for nature’s unpredictability. Slime is nature’s warning sign—heed it.

Freezing Fresh White Mushrooms: A Complete Guide to Preservation

You may want to see also

Proper storage to prevent mushroom slime

Mushrooms are highly perishable, and their slimy texture often signals spoilage, making them unsafe to eat. Proper storage is key to extending their freshness and preventing this unappetizing transformation. The primary culprit behind mushroom slime is excess moisture, which fosters bacterial growth. To combat this, start by storing mushrooms in a breathable environment. Paper bags or loosely wrapped paper towels work better than airtight containers or plastic bags, as they allow air circulation while absorbing excess moisture. Avoid washing mushrooms before storage, as this introduces the very moisture you’re trying to prevent. Instead, gently brush off dirt with a soft brush or cloth. For longer storage, consider refrigerating mushrooms in the paper bag or wrapping them in a damp (not wet) cloth placed inside a breathable container. This balances humidity without trapping moisture. If you’ve already washed mushrooms and need to store them, pat them completely dry before refrigerating in a paper towel-lined container. These simple steps can significantly reduce the risk of slime, keeping your mushrooms fresh and safe to eat.

While refrigeration is essential, temperature control alone isn’t enough to prevent mushroom slime. The ideal storage temperature for mushrooms is between 34°F and 38°F (1°C and 3°C), which slows down enzymatic activity and microbial growth. However, even within this range, improper handling can accelerate spoilage. For instance, overcrowding mushrooms in the fridge restricts airflow, creating pockets of moisture that promote slime. Store them in a single layer or in a spacious container to ensure even cooling. If you’ve purchased pre-packaged mushrooms in plastic, transfer them to a paper bag or ventilated container as soon as possible. For those who buy in bulk, consider dividing mushrooms into smaller portions to minimize exposure to air and moisture each time you open the storage container. Additionally, avoid placing mushrooms near ethylene-producing fruits like apples or bananas, as this gas accelerates ripening and spoilage. By combining proper temperature, ventilation, and organization, you can maximize mushroom freshness and minimize the dreaded slime.

For those who frequently cook with mushrooms, understanding their shelf life and storage nuances can save both money and meals. Fresh mushrooms typically last 5–7 days in the fridge when stored correctly, but this timeline can vary based on variety and initial freshness. Shiitake and cremini mushrooms, for example, tend to last longer than delicate oyster or enoki mushrooms. To further extend storage, consider blanching or sautéing mushrooms before freezing. Blanching involves submerging mushrooms in boiling water for 2–3 minutes, then plunging them into ice water to halt cooking. Once dried, store them in airtight freezer bags for up to 12 months. Sautéed mushrooms can be frozen in a single layer on a baking sheet before transferring to a storage bag, preventing them from clumping together. While frozen mushrooms may lose some texture, they retain flavor and are perfect for soups, stews, or sauces. This method is particularly useful for surplus mushrooms or seasonal varieties, ensuring you always have a supply on hand without risking slime.

Finally, while proper storage is crucial, it’s equally important to recognize when mushrooms have gone bad, regardless of how well they were stored. Slime is the most obvious sign, but other indicators include a strong, unpleasant odor, dark spots, or a noticeably softer texture. If you spot any of these, discard the mushrooms immediately, as consuming spoiled mushrooms can lead to foodborne illness. Even if only a portion of the batch is affected, it’s safest to throw out the entire container, as mold and bacteria can spread quickly. To minimize waste, adopt a first-in, first-out approach by using older mushrooms before newer purchases. Regularly inspect your fridge and discard any produce past its prime. By combining vigilant storage practices with a keen eye for spoilage, you can enjoy fresh, slime-free mushrooms in every dish.

Mushroom Cultivation in Whiskey Barrel Pellets: A Feasible Substrate?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.53

Cooking methods for slimy mushrooms

Slime on mushrooms often indicates spoilage, but certain varieties, like oyster or shiitake, naturally have a slimy texture when fresh. If the slime is a sign of decay, cooking won’t make them safe to eat. However, if the slime is inherent to the mushroom’s texture, specific cooking methods can enhance their flavor and reduce the sliminess. High heat is key—sautéing, stir-frying, or grilling at temperatures above 350°F (175°C) helps evaporate excess moisture and concentrates their umami richness. Always inspect mushrooms before cooking; discard any with off-odors, mold, or a dark, sticky slime.

For naturally slimy mushrooms, start by gently patting them dry with a paper towel to remove surface moisture. Avoid washing them, as this can exacerbate the slime. Heat a skillet over medium-high heat, add a tablespoon of oil (avocado or olive oil works well), and sear the mushrooms in a single layer for 3–4 minutes per side. Crowding the pan will steam them instead of browning, so cook in batches if necessary. This method creates a crispy exterior while maintaining a tender interior, minimizing the slimy texture.

Another effective technique is roasting. Preheat your oven to 425°F (220°C), toss the mushrooms in oil, salt, and herbs (thyme or garlic complement their earthy flavor), and spread them on a baking sheet. Roast for 15–20 minutes, stirring halfway through, until they’re golden and slightly shriveled. Roasting intensifies their flavor and reduces moisture, making the texture more palatable. For added depth, deglaze the pan with a splash of white wine or soy sauce after removing the mushrooms.

If you prefer a hands-off approach, try slow-cooking slimy mushrooms in soups or stews. Their natural moisture contributes to the broth, and prolonged cooking breaks down their texture, making them less noticeable. Add them in the last 20–30 minutes of cooking to retain some bite, or simmer them for over an hour to fully integrate their flavor. This method works best for hearty varieties like shiitake or portobello, which hold up well in liquid.

Finally, consider pickling as a transformative option. Brining naturally slimy mushrooms in a mixture of vinegar, water, salt, and spices (like mustard seeds or dill) not only preserves them but also alters their texture. Simmer the brine, pour it over the mushrooms in a sterilized jar, and refrigerate for at least 48 hours. Pickling firms up their flesh and adds a tangy contrast to their earthiness, making them a versatile addition to salads, sandwiches, or charcuterie boards. Always use fresh, firm mushrooms for pickling, as spoiled ones will not improve with this method.

Can Drug Dogs Detect Magic Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Common toxic mushrooms with slime to avoid

Slime on mushrooms often signals decay, but not all slimy mushrooms are toxic. However, certain toxic species can produce a slimy coating, making them particularly deceptive. Foraging enthusiasts must learn to identify these dangerous varieties to avoid accidental poisoning. Here’s a focused guide on common toxic mushrooms with slime to steer clear of.

One notorious example is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which can develop a slimy cap in wet conditions. This mushroom contains amatoxins, potent toxins that cause severe liver and kidney damage. Symptoms may not appear for 6–24 hours after ingestion, leading to dehydration, organ failure, and potentially death. Even a small bite can be fatal, making accurate identification critical. The Death Cap’s greenish-brown cap and white gills may appear innocuous, but its slimy texture in damp weather should raise red flags.

Another toxic species to avoid is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), often found in wooded areas. Its smooth, white cap can become slimy when moist, mimicking edible varieties like the button mushroom. However, it contains the same deadly amatoxins as the Death Cap. Foragers should note its volva (cup-like base) and lack of a ring on the stem, distinguishing it from safe lookalikes. If unsure, remember: white, slimy, and a volva is a deadly combination.

For practical safety, follow these steps: 1) Always cross-reference mushrooms with reliable field guides or apps. 2) Avoid picking mushrooms in wet conditions, as slime can obscure key identification features. 3) If a mushroom feels unusually slippery, err on the side of caution and discard it. 4) Never consume wild mushrooms without expert verification, especially if they exhibit slime. These precautions are non-negotiable for foragers of any experience level.

In comparison to edible slimy mushrooms like the Oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), toxic species often lack a distinct, pleasant aroma or have a more gelatinous slime. While Oyster mushrooms are safe and prized for their culinary use, their slimy texture in wet weather is harmless. Toxic varieties, however, often produce slime as a byproduct of decay or toxin secretion, making it a warning sign rather than a benign trait. Understanding these differences is key to safe foraging.

Finally, educating oneself about regional toxic species is essential. For instance, the Fool’s Mushroom (*Amanita verna*) in Europe or the Western Destroying Angel (*Amanita ocreata*) in North America both feature slimy caps and deadly toxins. Local mycological societies or foraging courses can provide region-specific knowledge. Remember, slime on a mushroom is not inherently dangerous, but when paired with toxic traits, it’s a clear signal to avoid. Always prioritize caution over curiosity in the wild.

Can Toddlers Eat Mushrooms? Nutrition, Safety, and Serving Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is generally not recommended to eat slimy mushrooms, as slime can indicate spoilage, bacterial growth, or decay, which may cause food poisoning or other health issues.

Mushrooms become slimy due to excess moisture, bacterial growth, or the breakdown of their cell structure as they age.

Not all slimy mushrooms are poisonous, but the slime is a sign of deterioration, making them unsafe to eat regardless of their original edibility.

Washing slimy mushrooms does not make them safe to eat. The slime indicates they are no longer fresh and should be discarded.

If a mushroom is even slightly slimy, it’s best to err on the side of caution and avoid consuming it, as the slime suggests it has begun to spoil.