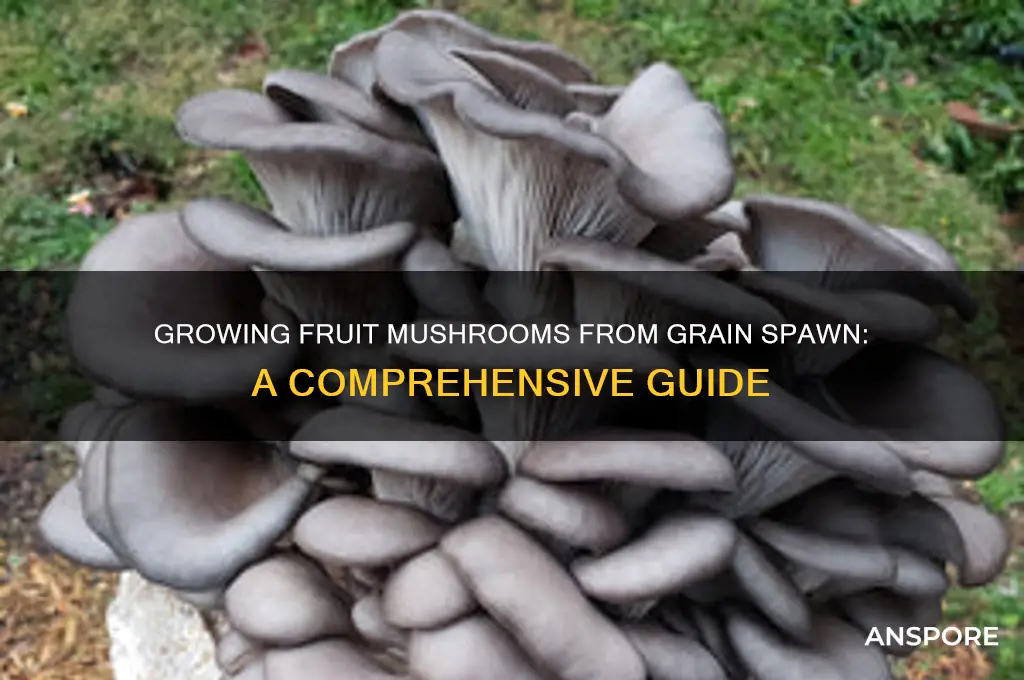

Growing mushrooms from grain spawn is a popular and efficient method for cultivating a variety of mushroom species, but the question of whether you can fruit mushrooms directly from grain spawn is nuanced. Grain spawn serves primarily as a nutrient-rich substrate for mycelium to colonize, acting as a stepping stone to bulk substrates like straw, wood chips, or compost, where fruiting typically occurs. While some mushroom species, such as oyster mushrooms, may occasionally fruit directly on grain spawn under optimal conditions, this is not the intended purpose of grain spawn. For consistent and abundant fruiting, transferring colonized grain spawn to a secondary substrate is generally recommended, as it provides the necessary environmental conditions and space for mushrooms to develop fully.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | Yes, mushrooms can be fruited from grain spawn. |

| Common Mushrooms | Oyster, Lion's Mane, Shiitake, and other saprotrophic mushrooms. |

| Grain Types | Wheat, rye, millet, sorghum, or a mix, depending on mushroom species. |

| Hydration Requirement | Grain spawn must be fully hydrated (field capacity) before fruiting. |

| Substrate Preparation | Pasteurized or sterilized bulk substrate (e.g., straw, sawdust, or compost) is required. |

| Environmental Conditions | High humidity (85-95%), proper temperature (species-specific), and fresh air exchange. |

| Fruiting Trigger | Light exposure, temperature shifts, or physical disturbance (e.g., dunking in water). |

| Yield | Varies by species and conditions; typically 20-50% of substrate weight in mushrooms. |

| Contamination Risk | Higher compared to sterile techniques; proper sanitation is critical. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | More affordable than agar or liquid culture methods for small-scale growers. |

| Timeframe | 2-6 weeks from spawn inoculation to first flush, depending on species and conditions. |

| Reusability | Spent substrate can sometimes be reused for secondary flushes or composted. |

| Limitations | Not suitable for all mushroom species (e.g., some mycorrhizal or wood-loving species). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Grain Spawn Preparation: Selecting and preparing grains for optimal mushroom mycelium colonization and growth

- Inoculation Techniques: Sterile methods to introduce mushroom spores or mycelium into grain spawn

- Incubation Process: Ideal conditions for grain spawn incubation, including temperature, humidity, and duration

- Fruiting Conditions: Transitioning colonized grain spawn to fruiting substrates for mushroom development

- Common Challenges: Troubleshooting contamination, slow colonization, or poor fruiting yields in grain spawn

Grain Spawn Preparation: Selecting and preparing grains for optimal mushroom mycelium colonization and growth

Selecting the right grains is the cornerstone of successful grain spawn preparation. Not all grains are created equal in the eyes of mushroom mycelium. Rye, wheat, and millet are popular choices due to their high nutrient content and ability to retain moisture, which fosters rapid mycelial colonization. Rye, in particular, is favored for its dense structure and low cost, making it ideal for species like shiitake and lion’s mane. Millet, though smaller, is excellent for oyster mushrooms due to its quick colonization time. Avoid grains like corn or barley, as their hard outer shells can hinder mycelium penetration, slowing growth and increasing contamination risk.

Preparation begins with cleaning and hydrating the grains. Start by rinsing them thoroughly to remove dust and debris, then soak them in cool water for 12–24 hours. This step rehydrates the grains, making them more receptive to mycelium. After soaking, drain and cook the grains using a pasteurization method. Boiling for 20–30 minutes or steaming until they reach an internal temperature of 160°F (71°C) kills contaminants while maintaining grain integrity. Overcooking can turn grains mushy, reducing their ability to support mycelium, while undercooking leaves them susceptible to bacteria and mold.

Once cooked, the grains must be cooled and dried to the optimal moisture level before inoculation. Spread them on a clean surface or tray, stirring occasionally to release steam and prevent clumping. Aim for a surface moisture content of 50–60%, which feels slightly damp to the touch but not wet. Too much moisture invites contamination, while too little stunts mycelial growth. Use a moisture meter for precision, or rely on the "squeeze test": a handful of grains should release 1–2 drops of water when tightly compressed.

Inoculation timing is critical. Introduce the mushroom mycelium to the grains when they are still warm (around 80–90°F or 27–32°C) but not hot, as extreme temperatures can kill the mycelium. Mix the spawn thoroughly to ensure even distribution, then transfer it to sterilized grow bags or jars. Seal the containers and incubate in a dark, temperature-controlled environment (70–75°F or 21–24°C) for 1–3 weeks, depending on the species. Regularly inspect for contamination, such as green or black mold, and discard any affected batches immediately.

The success of grain spawn preparation hinges on precision and attention to detail. From grain selection to post-inoculation care, each step influences the vigor and yield of the mushroom crop. By mastering these techniques, cultivators can create a robust foundation for fruiting, ensuring healthy mycelium and abundant harvests. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a commercial grower, the quality of your grain spawn will directly impact the success of your mushroom cultivation journey.

Storing Dried Magic Mushrooms: Room Temperature Tips and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Inoculation Techniques: Sterile methods to introduce mushroom spores or mycelium into grain spawn

Grain spawn serves as a nutrient-rich substrate for mushroom mycelium to colonize before fruiting, but successful inoculation hinges on sterile techniques to prevent contamination. Introducing spores or mycelium into grain requires precision and cleanliness to ensure the mycelium thrives without competition from molds or bacteria. Here’s how to master sterile inoculation methods for optimal results.

Step-by-Step Sterile Inoculation Process: Begin by sterilizing your grain substrate—typically rye, wheat, or millet—in a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 90 minutes to eliminate contaminants. Allow the grain to cool to around 80°F (27°C) in a clean environment to avoid cooking the mycelium. Meanwhile, prepare your inoculant: liquid culture or spore syringe. For liquid culture, use 10–20% of the grain’s volume; for spore syringes, inject 1–2 cc per quart of grain. Transfer the cooled grain to a sterile container or grow bag, then introduce the inoculant using a flame-sterilized needle or scalpel to pierce the bag and inject the solution. Seal the bag, mix gently to distribute the inoculant, and incubate at 70–75°F (21–24°C) in darkness until fully colonized.

Critical Cautions: Sterility is non-negotiable. Work in a still air box or laminar flow hood to minimize airborne contaminants. Flame-sterilize all tools before use, and avoid over-handling the grain or inoculant. Contamination often manifests as green, black, or fuzzy growth—if detected, discard the batch immediately. Additionally, ensure proper gas exchange by using breathable grow bags or punching small holes in the container to prevent anaerobic conditions that hinder mycelium growth.

Comparative Analysis of Inoculants: Liquid culture offers faster colonization (2–3 weeks) compared to spore syringes (4–6 weeks) due to its established mycelium network. However, spore syringes are more cost-effective and suitable for long-term storage. For beginners, liquid culture is recommended for its reliability and speed, while advanced cultivators may prefer spores for genetic diversity. Regardless of the method, maintaining sterility remains the cornerstone of successful inoculation.

Practical Tips for Success: Label all containers with dates and inoculant types to track progress. Use a hygrometer to monitor humidity during incubation, aiming for 60–70%. If using mason jars, cover the lids with foil and secure with a rubber band to prevent contamination while allowing gas exchange. Finally, bulk spawn by transferring colonized grain to a larger substrate like straw or sawdust to maximize fruiting potential. With meticulous attention to sterility and technique, grain spawn becomes a powerful tool for cultivating mushrooms at scale.

Shiitake Substitutes: Best Alternatives for Flavor and Texture in Recipes

You may want to see also

Incubation Process: Ideal conditions for grain spawn incubation, including temperature, humidity, and duration

The incubation process is a critical phase in fruiting mushrooms from grain spawn, as it determines the success and yield of your mushroom crop. To ensure optimal mycelial growth, specific conditions must be maintained, primarily focusing on temperature, humidity, and duration. These factors work in tandem to create an environment conducive to mycelium colonization, setting the stage for a bountiful harvest.

Temperature Control: The Goldilocks Zone

Maintaining the right temperature is akin to finding the Goldilocks zone – not too hot, not too cold, but just right. For most mushroom species, the ideal incubation temperature ranges between 70-75°F (21-24°C). This range promotes rapid mycelial growth without encouraging bacterial contamination. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) thrive in this temperature bracket, allowing their mycelium to colonize grain spawn efficiently. Deviating from this range can lead to slower growth or, worse, the proliferation of unwanted microbes. To achieve this, consider using a thermostat-controlled environment, such as an incubation chamber or a simple setup with a space heater and thermometer, ensuring the temperature remains consistent throughout the incubation period.

Humidity Management: The Moisture Balance

Humidity plays a pivotal role in the incubation process, as it directly impacts the moisture content of the grain spawn. The goal is to maintain a relative humidity (RH) of 60-70%. This level of moisture prevents the spawn from drying out while discouraging the growth of mold and bacteria. A simple yet effective method to regulate humidity is by using a humidifier or by placing a tray of water near the incubation container. For those seeking precision, a hygrometer can be employed to monitor RH levels, allowing for adjustments as needed. It's essential to strike a balance, as excessive humidity can lead to waterlogging, while insufficient moisture may hinder mycelial growth.

Duration: Patience is Key

The incubation duration varies depending on the mushroom species and environmental conditions. On average, grain spawn incubation takes 7-14 days, during which the mycelium colonizes the substrate. For example, shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) typically require a longer incubation period compared to lion's mane (*Hericium erinaceus*). It's crucial to resist the urge to rush this process, as premature exposure to fruiting conditions can result in poor yields. Regularly inspect the spawn for signs of full colonization, such as a uniform white mycelial mat covering the grains. Once achieved, the spawn is ready for the next stage, marking the end of a successful incubation process.

In the context of fruiting mushrooms from grain spawn, mastering the incubation process is a delicate art. By meticulously controlling temperature, humidity, and duration, cultivators can create an optimal environment for mycelial growth. This foundation is essential for a thriving mushroom crop, showcasing the importance of precision and patience in the fascinating world of mushroom cultivation. With these ideal conditions met, the stage is set for the transformative journey from spawn to fruit, a process that continues to captivate both hobbyists and commercial growers alike.

Mushroom Overeating: Risks, Benefits, and Safe Consumption Limits Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fruiting Conditions: Transitioning colonized grain spawn to fruiting substrates for mushroom development

Mushroom cultivation hinges on the delicate transition from colonization to fruiting, a process that demands precision in environmental conditions. Once grain spawn is fully colonized—typically evident by a dense, white mycelial network throughout the substrate—it’s primed for the next phase. However, simply transferring colonized grain to a fruiting substrate won’t guarantee success. The mycelium must encounter specific triggers to initiate fruiting: a shift in humidity, light exposure, and a drop in temperature. For instance, species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms) require a temperature drop from 24°C (colonization) to 15–18°C (fruiting) and increased fresh air exchange to stimulate pinhead formation.

The fruiting substrate itself plays a critical role in this transition. Unlike grain spawn, which serves as a nutrient-dense starter, fruiting substrates are often bulkier and more fibrous, such as straw, sawdust, or compost. These materials mimic the mushroom’s natural habitat, encouraging the mycelium to allocate energy toward fruiting rather than further colonization. For example, shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) thrive on supplemented sawdust substrates, while wine cap stropharia (*Stropharia rugosoannulata*) prefers wood chips mixed with straw. The key is to ensure the substrate is properly pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competitors while retaining enough nutrients for mushroom development.

Transitioning colonized grain spawn to fruiting substrates requires careful technique. Start by mixing 10–20% colonized grain into the fruiting substrate, ensuring even distribution to avoid dense mycelial clumps that can hinder fruiting. Maintain high humidity (85–95%) during the initial stages, often achieved with a misting schedule or humidification system. Light exposure, though minimal, is crucial—indirect natural light or a 12-hour photoperiod with fluorescent bulbs can trigger primordia formation. Avoid overwatering, as excess moisture can lead to bacterial contamination or drowning of the mycelium.

Caution must be exercised during this transition phase. Sudden environmental changes, such as drastic temperature fluctuations or exposure to drafts, can stress the mycelium and delay fruiting. Similarly, using unpasteurized substrates or introducing contaminants during the mixing process can derail the entire cycle. Monitoring pH levels (optimal range: 5.5–6.5 for most species) and adjusting as needed ensures the substrate remains hospitable. For advanced growers, experimenting with CO2 levels—keeping them below 1000 ppm during fruiting—can enhance mushroom yields.

Ultimately, successful fruiting from grain spawn relies on understanding the symbiotic relationship between mycelium and substrate. By providing the right conditions—temperature, humidity, light, and substrate composition—growers can coax the mycelium into producing abundant, healthy mushrooms. This transition is both an art and a science, requiring patience, observation, and adaptability. Whether cultivating oyster mushrooms in a small grow tent or shiitakes in a commercial setting, mastering this phase unlocks the full potential of grain spawn as a foundational tool in mushroom cultivation.

Blue Cheese on Wild Mushroom Risotto: A Gourmet Match?

You may want to see also

Common Challenges: Troubleshooting contamination, slow colonization, or poor fruiting yields in grain spawn

Contamination is the bane of any mushroom cultivator, and grain spawn is particularly susceptible due to its high nutrient content. Molds, bacteria, and competing fungi can quickly overrun your spawn, rendering it unusable. Common culprits include improper sterilization—ensure your grain is fully sterilized at 121°C (250°F) for at least 90 minutes—and inadequate hygiene during inoculation. Even a single spore introduced during transfer can multiply rapidly. To mitigate, use a still-air box or glove box to maintain a sterile environment, and always flame-sterilize tools before use. If contamination appears, isolate the affected spawn immediately to prevent spread, and consider using a more resilient grain like rye or millet in future batches.

Slow colonization can frustrate even experienced growers, often stemming from suboptimal conditions or low-viability spawn. Grain spawn thrives in temperatures between 24–28°C (75–82°F), so ensure your incubation area remains within this range. Humidity should be moderate—around 60–70%—to prevent drying without encouraging contamination. If colonization stalls, verify the spawn’s viability by testing a small sample before scaling up. Additionally, avoid overpacking jars or bags, as poor airflow can hinder mycelial growth. For stubborn cases, introduce a small amount of gypsum (1–2% by weight) to the grain to improve structure and nutrient availability.

Poor fruiting yields often result from inadequate transition from colonization to fruiting conditions. Grain spawn requires a shock—such as exposure to fresh air, light, and cooler temperatures—to initiate pinning. Gradually reduce incubation temperatures to 18–22°C (64–72°F) and introduce indirect light (12–16 hours daily). Mist the spawn lightly to maintain surface moisture without saturating it, as excess water can lead to rot. If yields remain low, consider supplementing with a small amount of hydrated lime (0.5–1% by weight) to adjust pH and encourage fruiting. Patience is key; some species, like shiitake, may take weeks to form primordia.

Comparing grain spawn to other substrates highlights its unique challenges. Unlike sawdust or straw, grain’s dense structure can restrict airflow and retain moisture, increasing contamination risk. However, its nutrient density offers faster colonization when conditions are optimal. For example, oyster mushrooms often fruit more prolifically on grain than on straw, but they require meticulous attention to humidity and ventilation. By understanding these trade-offs, growers can tailor their approach—using grain for rapid colonization and transitioning to bulk substrates for fruiting, or fruiting directly from grain in controlled environments. Each method has its merits, but success hinges on addressing grain spawn’s specific vulnerabilities.

Slimy Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Toss? Expert Advice

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can fruit mushrooms directly from grain spawn, but it depends on the mushroom species and growing conditions. Some mushrooms, like oyster mushrooms, can fruit directly on grain spawn, while others may require a secondary substrate like sawdust or straw.

Mushrooms like oyster, lion's mane, and some shiitake strains can fruit directly from grain spawn. However, species like reishi or maitake typically require a different substrate for fruiting.

Not always. For species that fruit well on grain, you can skip the transfer step. However, for better yields or specific species, transferring to a bulk substrate like straw or sawdust is recommended.

Fruiting time varies by species and conditions, but it typically takes 1-3 weeks after the grain spawn is fully colonized. Proper humidity, temperature, and light are crucial for successful fruiting.