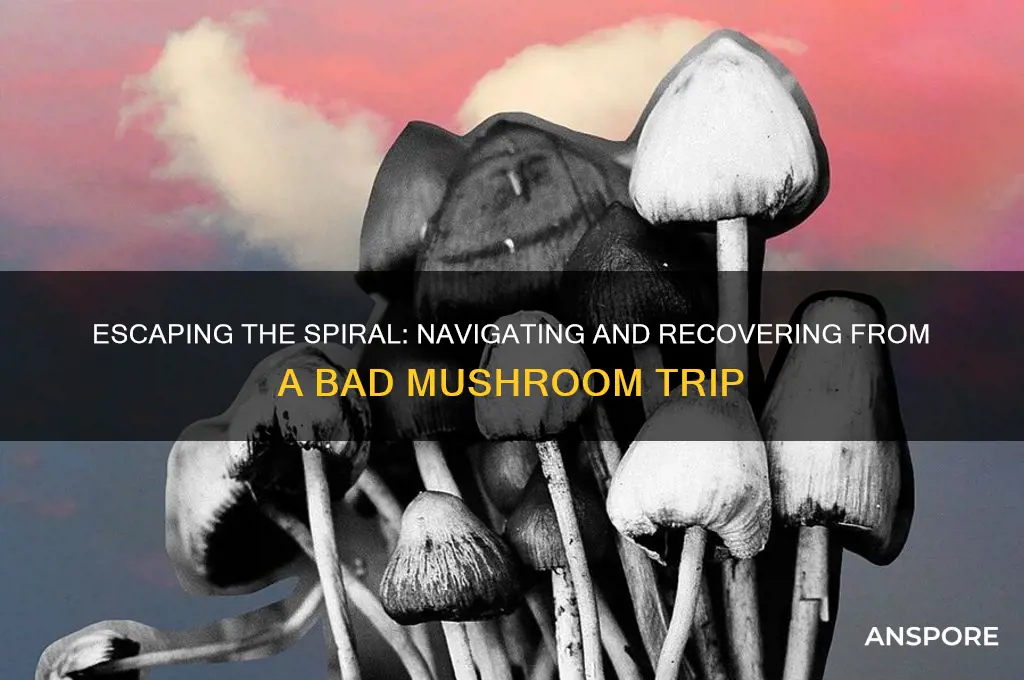

The idea of getting stuck in a bad mushroom trip, often referred to as a psychedelic or hallucinogenic experience, is a common concern among users and those curious about psychedelics like psilocybin mushrooms. While the effects of a mushroom trip are typically temporary, lasting between 4 to 6 hours, some individuals may experience prolonged psychological distress or a phenomenon known as Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD). This rare condition involves flashbacks or recurring sensory disturbances long after the substance has left the system. However, being stuck in a bad trip in the sense of permanent psychological damage is not supported by mainstream scientific evidence, though intense experiences can have lasting emotional impacts. Proper preparation, setting, and guidance are crucial to minimizing risks and ensuring a safer experience.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Duration of a Bad Trip | Typically lasts 6-12 hours, but psychological effects can persist longer. |

| Common Symptoms | Anxiety, paranoia, confusion, hallucinations, and emotional distress. |

| Long-Term Psychological Impact | Possible development of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) or exacerbation of pre-existing mental health conditions. |

| Physical Symptoms | Increased heart rate, nausea, sweating, and coordination issues. |

| Factors Influencing Severity | Dosage, setting, mindset, and individual sensitivity to psilocybin. |

| Can You Get "Stuck"? | No, effects are temporary, but psychological distress may feel prolonged. |

| Treatment for a Bad Trip | Calm environment, reassurance, and in severe cases, medical intervention. |

| Prevention Strategies | Proper dosing, trusted setting, and avoiding use with mental health issues. |

| Legal Status of Psilocybin Mushrooms | Illegal in most countries, though some regions allow medical/therapeutic use. |

| Research on Long-Term Effects | Limited, but studies suggest potential therapeutic benefits with controlled use. |

Explore related products

$54.99

What You'll Learn

- Duration of Effects: How long can intense, negative experiences last during a bad mushroom trip

- Psychological Impact: What are the potential mental health risks of a severe trip

- Physical Symptoms: Can physical discomfort or distress occur during a bad experience

- Recovery Methods: What strategies help individuals recover from a negative mushroom trip

- Prevention Tips: How can users minimize the risk of a bad trip beforehand

Duration of Effects: How long can intense, negative experiences last during a bad mushroom trip?

A bad mushroom trip can feel like an eternity, but the duration of intense, negative experiences is typically finite. Psilocybin, the active compound in magic mushrooms, is metabolized relatively quickly, with peak effects occurring within 1–2 hours after ingestion. However, the subjective experience of time distortion can make minutes feel like hours. For most users, the acute phase of a trip lasts 4–6 hours, though residual effects like heightened sensitivity or emotional turbulence may linger for several more hours. Understanding this timeline can provide a sense of control during a challenging experience.

Dosage plays a critical role in determining the intensity and duration of a bad trip. Low to moderate doses (0.5–2 grams of dried mushrooms) often result in milder, shorter-lived negative effects, such as anxiety or paranoia, which may subside within 2–4 hours. Higher doses (3 grams or more) can prolong and intensify the experience, with distressing hallucinations, emotional overwhelm, or ego dissolution lasting up to 6–8 hours. Users should note that individual tolerance, set (mindset), and setting (environment) also influence how long negative effects persist. For instance, a supportive setting can help shorten the perceived duration of a bad trip by fostering reassurance and grounding.

Comparatively, the duration of a bad mushroom trip is shorter than that of other psychedelics like LSD, which can last 10–12 hours. However, the intensity of psilocybin’s effects can make even a 4-hour experience feel overwhelming. Practical strategies to manage time during a bad trip include focusing on breathing exercises, listening to calming music, or engaging in gentle physical activity. Time-based anchors, such as setting a timer for 30-minute intervals, can also help users track progress and remind them that the experience is temporary.

For those concerned about prolonged negative effects, it’s crucial to differentiate between the acute trip and potential psychological aftermath. While the intense phase rarely exceeds 8 hours, some users report lingering anxiety, confusion, or existential distress for days or weeks afterward. This phenomenon, often referred to as a "psychedelic afterglow" or "integration phase," is not the same as being "stuck" in a bad trip. Instead, it reflects the mind’s processing of the experience. Seeking support from a therapist or trusted friend can aid in navigating this period effectively.

In summary, while a bad mushroom trip can feel interminable, the duration of intense, negative effects is typically limited to 4–8 hours, depending on dosage and individual factors. Understanding this timeline, coupled with practical coping strategies, can empower users to endure and eventually emerge from the experience. Remember, time is a constant ally—even when it feels distorted.

Freezing Baked Phyllo Mushroom Pockets: Tips for Perfect Storage

You may want to see also

Psychological Impact: What are the potential mental health risks of a severe trip?

A severe mushroom trip can trigger latent mental health conditions or exacerbate existing ones, often with long-lasting effects. For individuals predisposed to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe anxiety, high doses of psilocybin (typically above 3 grams) can act as a catalyst, accelerating the onset of psychotic episodes or manic states. This phenomenon, known as "unmasking," occurs when the drug interacts with an individual’s neurochemical vulnerabilities, potentially leading to permanent changes in perception or mood regulation. Unlike a temporary "bad trip," these outcomes may persist for months or years, requiring clinical intervention.

Consider the case of a 25-year-old with undiagnosed schizophrenia who consumed 5 grams of dried psilocybin mushrooms. Within hours, they experienced persistent auditory hallucinations and paranoia, symptoms that did not resolve after the trip ended. Such cases highlight the importance of screening for family histories of mental illness before experimenting with psychedelics. Even in recreational settings, the absence of a controlled environment and proper dosing (e.g., starting with 1–2 grams for inexperienced users) increases the risk of psychological trauma.

From a persuasive standpoint, the allure of self-exploration through psychedelics must be balanced with awareness of their power. A severe trip can leave individuals with depersonalization-derealization disorder, a condition where one feels detached from reality or oneself. This is not merely a fleeting sensation but a debilitating state that can impair daily functioning. Studies show that repeated exposure to high-stress psychedelic experiences, particularly without integration therapy, correlates with higher rates of this disorder among users under 30.

Comparatively, the psychological risks of a bad trip differ from those of substance abuse but share a critical similarity: both can create cycles of avoidance or maladaptive coping. For instance, someone who experiences severe ego dissolution during a trip may develop agoraphobia, fearing future loss of control. Conversely, another might chase the intensity of the experience, leading to reckless dosing practices. The key distinction lies in the immediacy of psychedelic effects—a single high-dose trip (e.g., 4+ grams) can alter neural pathways in ways that years of moderate use might not.

Practically, mitigating these risks involves harm reduction strategies. Always test mushrooms for potency, as misidentification or contamination can amplify adverse effects. For those with a history of mental health issues, abstaining from psychedelics is advisable. If a trip turns severe, grounding techniques—such as focusing on tactile sensations or listening to calming music—can help stabilize the individual. Post-trip, seeking therapy to process the experience is crucial, especially if symptoms like persistent anxiety or mood disturbances arise. Remember, the goal is not to fear psychedelics but to respect their capacity to reshape the mind.

Freezing Fresh Mushrooms: A Salad-Saver's Guide to Preservation

You may want to see also

Physical Symptoms: Can physical discomfort or distress occur during a bad experience?

A bad mushroom trip can manifest physically, not just mentally. Users often report nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, likely due to the body’s reaction to psilocybin or mycotoxins present in certain mushrooms. These symptoms can escalate if the dosage exceeds 2–3 grams of dried mushrooms, a threshold where the body’s tolerance may be overwhelmed. For instance, a 2019 study published in *Harm Reduction Journal* noted gastrointestinal distress in 30% of participants who consumed more than 3 grams, suggesting a clear correlation between high doses and physical discomfort.

Beyond the digestive system, cardiovascular symptoms like increased heart rate, hypertension, and palpitations are common during intense trips. These effects are particularly pronounced in individuals with pre-existing heart conditions or those over 40, whose cardiovascular systems may be less resilient. A rapid heart rate, often exceeding 100 bpm, can mimic anxiety, creating a feedback loop where physical symptoms amplify psychological distress. Monitoring heart rate during use and avoiding mushrooms if you have cardiovascular risks is a practical precaution.

Muscle tension and coordination issues are another physical hallmark of a bad trip. Users may experience tremors, rigidity, or even temporary paralysis in extreme cases. These symptoms are thought to stem from psilocybin’s interaction with serotonin receptors in the brain, which regulate motor control. For example, a 2021 case study in *Psychopharmacology* described a 28-year-old user who developed dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions) after consuming 5 grams of mushrooms, a dose far exceeding the typical 1–2 gram recreational range.

Finally, hyperthermia and chills are less discussed but equally distressing physical symptoms. Psilocybin can disrupt the body’s thermoregulation, leading to sudden spikes or drops in temperature. Users may feel feverish or shiver uncontrollably, adding to the overall sense of unease. Staying hydrated, maintaining a stable environment, and having a sober companion to monitor for signs of overheating are essential harm reduction strategies. While these physical symptoms are usually temporary, they underscore the importance of mindful dosing and preparation when using mushrooms.

Pescatarians and Mushrooms: Are Fungi Fair Game in Your Diet?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$54.95

Recovery Methods: What strategies help individuals recover from a negative mushroom trip?

A bad mushroom trip can be an overwhelming and distressing experience, leaving individuals feeling trapped in a cycle of anxiety, paranoia, or disconnection from reality. However, recovery is possible, and certain strategies can help mitigate the intensity and duration of these negative effects. One of the most immediate and effective methods is grounding techniques, which anchor the individual in the present moment. For example, focusing on physical sensations—like the texture of an object or the rhythm of one’s breath—can help disrupt the spiral of negative thoughts. A simple yet powerful exercise is the "5-4-3-2-1" method: identify five things you can see, four you can touch, three you can hear, two you can smell, and one you can taste. This sensory engagement pulls the mind away from the trip’s intensity and back to the here and now.

Another critical recovery method involves social support. Having a trusted friend or "trip sitter" present can make a significant difference. This person should remain calm, reassuring, and non-judgmental, offering gentle reminders that the experience is temporary. For those without immediate support, reaching out to a helpline or online community can provide comfort. Research shows that social connection reduces feelings of isolation, a common factor in prolonged negative trips. It’s essential, however, to avoid confrontational or dismissive interactions, as these can exacerbate distress. Instead, phrases like "You’re safe, and this will pass" can help stabilize the individual’s emotional state.

Physical environment adjustments also play a pivotal role in recovery. A cluttered or overstimulating space can intensify a bad trip, so creating a calm, familiar setting is crucial. Dim lighting, soft music, and comfortable temperatures can help soothe the senses. If outdoors, moving to a quieter, shaded area can reduce sensory overload. For those experiencing severe anxiety, lying down in a safe, enclosed space (like a bed with blankets) can provide a sense of security. Avoiding screens or loud noises is equally important, as these can prolong disorientation.

In some cases, pharmacological interventions may be necessary, particularly if the individual is at risk of self-harm or severe panic. Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, are commonly used in medical settings to reduce anxiety and agitation during psychedelic crises. However, these should only be administered by a healthcare professional, as improper use can lead to adverse effects. For milder cases, over-the-counter antihistamines like diphenhydramine (25–50 mg) can help alleviate restlessness, though they should be used cautiously due to potential drowsiness. It’s worth noting that these medications do not "reverse" the trip but rather manage symptoms until the effects wear off.

Finally, post-trip integration is a vital but often overlooked recovery method. After the acute experience subsides, reflecting on the trip in a structured way can help process emotions and prevent long-term psychological impact. Journaling, therapy, or guided meditation can aid in making sense of the experience. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques can help reframe negative thoughts, while mindfulness practices can foster resilience. Studies suggest that individuals who engage in post-trip integration are less likely to experience persistent anxiety or flashbacks. This step transforms a challenging experience into an opportunity for growth, ensuring the individual emerges stronger and more self-aware.

Can Mushrooms Grow in Your Ears? Debunking Myths and Facts

You may want to see also

Prevention Tips: How can users minimize the risk of a bad trip beforehand?

A bad mushroom trip can be an intensely distressing experience, but many of its risks are preventable with careful preparation. One of the most critical factors is dosage control. Psilocybin mushrooms vary widely in potency, and taking too much can overwhelm even experienced users. Start with a low dose—1 to 1.5 grams of dried mushrooms for beginners—and wait at least two hours before considering a second dose. This approach allows you to gauge the effects gradually and avoid spiraling into an uncontrollable state. Always err on the side of caution; a lighter trip is far easier to manage than one that feels inescapable.

Beyond dosage, set and setting play a pivotal role in shaping the experience. "Set" refers to your mindset—emotional state, expectations, and mental health. Avoid mushrooms if you’re feeling anxious, depressed, or overwhelmed, as these emotions can amplify during the trip. Instead, choose a time when you’re calm, curious, and open-minded. "Setting" involves your physical and social environment. Opt for a safe, familiar, and comfortable space, ideally with a trusted friend or "trip sitter" who remains sober. Natural settings like forests or parks can enhance the experience, but ensure you’re in a secure location with no risks of getting lost or injured.

Another often-overlooked prevention strategy is research and education. Understanding what to expect can reduce fear and confusion during the trip. Familiarize yourself with the typical effects of psilocybin, including altered perception, emotional intensity, and potential spiritual insights. Knowing that a bad trip is temporary and not indicative of long-term harm can help you ride out challenging moments. Additionally, avoid mixing mushrooms with other substances, especially alcohol or stimulants, as these can exacerbate anxiety or disorientation.

Finally, physical and mental preparation can significantly reduce the risk of a bad trip. Ensure you’re well-rested, hydrated, and have eaten a light meal beforehand to avoid discomfort. Some users find that meditation or deep breathing exercises before the trip can center their mind and enhance the experience. If you have a history of mental health issues, particularly psychosis or severe anxiety, reconsider using mushrooms altogether, as they can trigger latent conditions. Prevention is about respect for the substance and yourself—taking these steps can transform a potentially daunting experience into a meaningful and manageable journey.

Maximizing Mushroom Freshness: Shelf Life After Opening Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While a bad mushroom trip can feel overwhelming and prolonged, the effects are temporary and typically last 4-6 hours. Psychological symptoms may linger, but permanent mental states are rare.

Stay in a safe, calm environment with a trusted person. Focus on breathing, remind yourself the effects are temporary, and avoid resisting the experience. Seek medical help if severe anxiety or panic occurs.

In some cases, a traumatic trip can trigger or exacerbate underlying mental health conditions like anxiety or PTSD. However, this is not common and often depends on individual predispositions.

There’s no instant fix, but grounding techniques, hydration, and a change of environment can help. Benzodiazepines, under medical supervision, may be used in extreme cases to reduce anxiety.