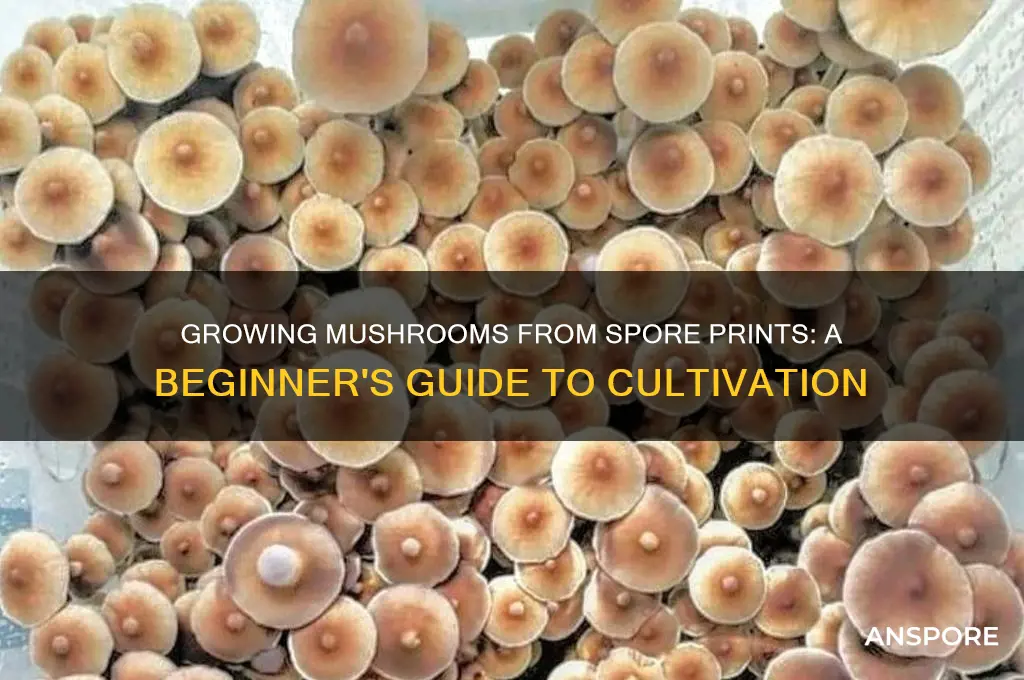

Growing mushrooms from a spore print is a fascinating and accessible way for enthusiasts to cultivate their own fungi at home. A spore print, which is essentially a collection of spores released from the gills or pores of a mature mushroom cap, serves as the starting point for this process. By carefully transferring these spores onto a suitable substrate, such as agar or grain, cultivators can initiate the growth of mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. With proper care, including maintaining optimal humidity, temperature, and light conditions, the mycelium will eventually produce new mushrooms. While the process requires patience and attention to detail, it offers a rewarding way to explore the life cycle of mushrooms and experiment with different species, making it a popular activity among both hobbyists and mycologists.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | Yes, it is possible to grow mushrooms from a spore print. |

| Process | Involves transferring spores to a sterile substrate (e.g., agar, grain spawn) to initiate mycelium growth. |

| Materials Needed | Spore print, sterile substrate, agar plates (optional), sterile tools, and a controlled environment. |

| Success Rate | Varies by mushroom species and technique; generally lower than using mycelium cultures but still viable. |

| Timeframe | Can take several weeks to months, depending on species and growing conditions. |

| Sterility | Requires strict sterile techniques to prevent contamination from bacteria, molds, or other fungi. |

| Species Compatibility | Works for most mushroom species, but some may be more challenging or require specific conditions. |

| Advantages | Allows for genetic diversity, experimentation, and preservation of rare mushroom strains. |

| Disadvantages | Higher risk of contamination, longer process, and less predictable results compared to using mycelium cultures. |

| Common Substrates | Agar, grain spawn, or pasteurized soil/compost, depending on the mushroom species. |

| Environmental Needs | Controlled temperature, humidity, and light conditions specific to the mushroom species. |

| Legal Considerations | Check local laws, as growing certain mushroom species may be regulated or prohibited. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Mycelium: Understanding the difference between spores and mycelium in mushroom cultivation

- Sterilization Techniques: Essential methods to prevent contamination when working with spore prints

- Substrate Preparation: Choosing and preparing the right growing medium for spore germination

- Incubation Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light for successful spore growth

- Transfer to Bulk: Moving colonized mycelium to larger substrates for fruiting mushrooms

Spores vs. Mycelium: Understanding the difference between spores and mycelium in mushroom cultivation

Mushroom cultivation begins with understanding the fundamental units of fungal life: spores and mycelium. Spores are the microscopic, seed-like structures fungi produce to reproduce, akin to plant seeds. They are dispersed through air, water, or animals and can remain dormant for years until conditions are favorable for growth. Mycelium, on the other hand, is the vegetative part of the fungus—a network of thread-like filaments called hyphae that absorb nutrients and grow beneath the surface. While spores are the starting point, mycelium is the workhorse of mushroom cultivation, responsible for nutrient uptake and fruiting body formation.

To grow mushrooms from a spore print, you’re essentially capturing and cultivating these spores to develop into mycelium. A spore print is made by placing the cap of a mature mushroom gills-down on a surface, allowing spores to drop. These spores can then be transferred to a sterile substrate, such as agar or grain, to initiate mycelial growth. However, this process is not immediate. Spores require specific conditions—moisture, warmth, and oxygen—to germinate. Once germinated, they form hyphae, which intertwine to create mycelium. This stage can take weeks, depending on the species and environmental factors.

The choice between using spores or mycelium for cultivation depends on your goals and resources. Spores offer genetic diversity, making them ideal for breeding new strains or experimenting with varieties. However, they are unpredictable; each spore carries unique traits, and not all will grow into desirable mushrooms. Mycelium, often obtained from tissue cultures or spawn, provides consistency and faster results. It bypasses the germination phase, allowing growers to focus on fruiting conditions. For beginners, mycelium-based methods like using grain spawn are more reliable, while advanced cultivators may prefer spores for their potential in innovation.

Practical tips for working with spores include maintaining sterility to prevent contamination, as spores are highly susceptible to mold and bacteria. Use a still air box or laminar flow hood when handling spore prints or inoculating substrates. For mycelium, ensure proper hydration and temperature to encourage healthy growth. For example, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) thrive at 70–75°F (21–24°C), while shiitake (Lentinula edodes) prefer 60–65°F (15–18°C). Always monitor pH levels, as mycelium grows best in slightly acidic to neutral conditions (pH 5.5–7.0).

In conclusion, while spores and mycelium are both essential in mushroom cultivation, they serve distinct roles. Spores are the starting point for genetic diversity but require patience and precision. Mycelium is the engine of growth, offering consistency and efficiency. Understanding their differences allows cultivators to choose the best method for their needs, whether experimenting with new strains or producing reliable yields. Mastery of these concepts transforms mushroom cultivation from guesswork into a science.

Can Mushrooms Be Detected in Hair Follicle Tests?

You may want to see also

Sterilization Techniques: Essential methods to prevent contamination when working with spore prints

Growing mushrooms from a spore print is a delicate process that hinges on one critical factor: maintaining a sterile environment. Contamination by bacteria, mold, or other fungi can derail your efforts before they even begin. Here’s why sterilization techniques are non-negotiable and how to master them.

The Science Behind Sterilization: Spores are resilient, but the substrate they grow on is a magnet for competitors. Sterilization eliminates these rivals by destroying their cells or rendering them inactive. Common contaminants thrive in the same conditions as mushrooms, so a single overlooked bacterium can multiply rapidly, consuming nutrients meant for your mycelium. Autoclaving, a method using steam under pressure (15 psi at 121°C for 30–60 minutes), is the gold standard for sterilizing substrates like grain or agar. For smaller tools, a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution kills surface microbes on contact, but it’s ineffective against spores—hence the need for heat-based methods.

Practical Sterilization Techniques: For home cultivators, pressure cookers mimic autoclaves, ensuring substrates reach the necessary temperature to kill contaminants. When sterilizing glassware or metal tools, flaming with a torch or dipping in alcohol is sufficient. However, spore prints themselves should never be heated; instead, store them in a desiccator or airtight container with silica gel to maintain dryness and prevent degradation. Always work in a still air box or laminar flow hood to minimize airborne contaminants during inoculation.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them: Overcrowding your sterilizer reduces efficiency, as steam may not penetrate all materials evenly. Leave space between jars or bags, and use a thermometer to verify temperature. Another mistake is reusing contaminated equipment without proper cleaning. Scrub tools with detergent, rinse thoroughly, and sterilize before reuse. Lastly, rushing the cooling process can introduce contaminants; allow substrates to cool naturally in a clean environment.

Advanced Tips for Success: Incorporate a sterilization schedule into your workflow. Label tools and substrates with sterilization dates to track freshness. For agar work, prepare a master mix in bulk, sterilize it, and store it in a fridge for up to two weeks. When transferring spore prints, use a scalpel sterilized with a flame and a glass slide wiped with alcohol to minimize contact points. Finally, maintain a clean workspace by regularly wiping surfaces with a 10% bleach solution and wearing gloves to reduce human-borne contaminants.

Mastering sterilization transforms mushroom cultivation from a gamble into a science. By understanding the principles, employing the right tools, and avoiding common errors, you’ll create an environment where your spore print can thrive uncontested.

Mushrooms as Musical Instruments: Exploring Nature's Sonic Potential

You may want to see also

Substrate Preparation: Choosing and preparing the right growing medium for spore germination

The success of growing mushrooms from a spore print hinges on the substrate—the growing medium that provides nutrients and structure for mycelium development. Unlike plants, mushrooms don’t photosynthesize; they rely entirely on their substrate for energy. Choosing the wrong material or preparing it improperly can lead to contamination or poor colonization. Common substrates include straw, wood chips, sawdust, and grain, each with unique properties suited to different mushroom species. For instance, oyster mushrooms thrive on straw, while shiitakes prefer hardwood sawdust. Understanding these preferences is the first step in substrate preparation.

Preparation begins with sterilization or pasteurization to eliminate competing microorganisms. Sterilization, typically done in a pressure cooker, is essential for grain-based substrates like rye or millet, which are prone to contamination. For example, soak rye grains in water for 24 hours, drain, and steam or pressure cook at 15 psi for 90 minutes. Pasteurization, a gentler process, is suitable for straw or wood chips. Submerge the material in hot water (180°F) for 1–2 hours, then drain and cool. Both methods ensure a clean environment for spore germination, though pasteurization retains some beneficial microbes that can deter contaminants.

The next step is supplementation. Most substrates lack sufficient nutrients for optimal mushroom growth and require amendments like gypsum, vermiculite, or bran. For example, a common recipe for sawdust-based substrates includes 70% hardwood sawdust, 20% bran, and 10% gypsum. Gypsum regulates pH and prevents grain substrates from clumping, while vermiculite retains moisture. Mixing these components thoroughly ensures even nutrient distribution. The substrate should feel damp but not waterlogged—aim for a moisture content of 60–70%, similar to a wrung-out sponge.

Finally, the substrate must be inoculated with the spore print. Spores are delicate and require a sterile environment to germinate. Introduce the spore print by gently pressing it onto the substrate’s surface or mixing it with a small amount of distilled water and spraying it evenly. Seal the inoculated substrate in a sterile container or bag to maintain humidity and prevent contamination. Keep it in a dark, warm environment (70–75°F) to encourage mycelium growth. Patience is key—colonization can take weeks, depending on the species and conditions.

In summary, substrate preparation is a precise science that balances sterilization, supplementation, and inoculation. By tailoring the medium to the mushroom species and following meticulous steps, growers can create an ideal environment for spore germination. Whether using straw, grain, or sawdust, the goal is to provide a clean, nutrient-rich foundation for mycelium to flourish. With careful attention to detail, even beginners can transform a simple spore print into a thriving mushroom colony.

Transforming Mushrooms: Techniques to Make Them Taste Like Meat

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Incubation Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light for successful spore growth

Spores, the microscopic seeds of fungi, require precise environmental conditions to germinate and develop into mycelium, the vegetative part of a mushroom. Among the critical factors, temperature, humidity, and light play pivotal roles in determining the success of spore growth. Understanding and controlling these conditions can significantly enhance the likelihood of a thriving mushroom cultivation project.

Temperature: The Goldilocks Zone

Mushroom spores thrive in temperatures that are neither too hot nor too cold—typically between 70°F and 75°F (21°C to 24°C). This range mimics the natural environment where many mushroom species flourish. Deviating from this zone can stall germination or encourage contaminants. For example, temperatures below 60°F (15°C) slow metabolic processes, while temperatures above 80°F (27°C) may stress the spores or favor bacterial growth. Use a thermostat-controlled environment, such as an incubation chamber or a simple setup with a heating pad and thermometer, to maintain consistency. Avoid placing spore prints near windows or vents where temperatures fluctuate.

Humidity: The Lifeline of Spore Germination

High humidity, ideally between 90% and 100%, is essential during incubation. Spores absorb moisture to activate their metabolic processes, and dry conditions can render them dormant or inviable. To achieve this, place the spore print in a sealed container with a damp paper towel or use a humidity-controlled environment like a still air box. Misting the container lightly with sterile water can help maintain moisture levels, but avoid over-saturating to prevent waterlogging. A hygrometer is a valuable tool to monitor humidity accurately. If humidity drops below 80%, germination rates plummet, and the risk of contamination rises.

Light: The Subtle Influencer

Unlike plants, spores do not require light for germination, but indirect, diffused light can stimulate mycelium growth once spores have sprouted. During the initial incubation phase, keep the environment in near darkness to prevent algae growth and conserve energy for spore development. Once mycelium becomes visible, introduce low-intensity light (e.g., a 12-hour photoperiod with a fluorescent bulb) to encourage directional growth. Direct sunlight is harmful, as it can overheat the substrate and dry out the environment. Think of light as a gentle nudge rather than a necessity—its role is secondary to temperature and humidity but still impactful.

Practical Tips for Success

Sterilization is paramount; clean all equipment with alcohol before use to prevent contamination. Use a spore syringe or scalpel to transfer spores onto a sterile substrate like agar or grain spawn. Label containers with dates and conditions for tracking progress. Patience is key—spore germination can take 7 to 21 days, depending on the species. Regularly inspect the setup for signs of mold or bacteria, and discard contaminated cultures immediately. For beginners, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are a forgiving species to start with, as they tolerate minor fluctuations in conditions.

Takeaway: Precision Pays Off

Mastering incubation conditions is both an art and a science. By maintaining optimal temperature, humidity, and light, you create an environment where spores can thrive. Small adjustments can yield significant results, transforming a spore print into a flourishing mycelium network. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional cultivator, attention to detail in these areas will set the foundation for a successful mushroom-growing journey.

Post-Mushroom Insomnia: Why Can't You Sleep After Eating Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Transfer to Bulk: Moving colonized mycelium to larger substrates for fruiting mushrooms

Growing mushrooms from a spore print is a fascinating process, but the real magic happens when you transfer colonized mycelium to bulk substrates for fruiting. This step is crucial because mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, needs ample space and nutrients to produce mushrooms. Once your mycelium has fully colonized a smaller container, such as a grain spawn jar, it’s time to introduce it to a larger, nutrient-rich environment like straw, wood chips, or compost. This transition mimics the mushroom’s natural habitat, where it thrives in decaying organic matter.

The process begins with selecting the right bulk substrate. For example, oyster mushrooms prefer straw, while shiitakes favor hardwood sawdust. Pasteurize or sterilize the substrate to eliminate competing organisms, ensuring your mycelium has the best chance to dominate. Mix the colonized grain spawn into the substrate thoroughly, aiming for a spawn-to-substrate ratio of 1:10 to 1:20, depending on the mushroom species. This ensures even distribution and maximizes colonization efficiency.

After mixing, transfer the inoculated substrate into a larger container, such as a monotub or grow bag, and maintain optimal conditions: 70-75°F (21-24°C) and high humidity. Within weeks, the mycelium will colonize the bulk substrate, forming a dense, white network. At this stage, introduce fruiting conditions by reducing temperature slightly, increasing fresh air exchange, and misting the surface to trigger mushroom formation.

One common mistake is rushing the transfer or using contaminated substrate, which can lead to mold or bacterial growth. Always work in a clean environment, use gloves, and consider a still-air box for sensitive species. Patience is key—colonization can take 2-6 weeks, depending on the substrate and species. With proper care, this step transforms a small spore print into a bountiful harvest, showcasing the resilience and productivity of mycelium in its expanded domain.

Best King Oyster Mushroom Substitutes for Your Recipes: Top Picks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can grow mushrooms from a spore print by using it to inoculate a sterile substrate, such as agar or grain spawn, which will then colonize and produce mycelium, eventually leading to mushroom fruiting.

To make a spore print, place the cap of a mature mushroom gills-down on a piece of foil or glass, cover it with a bowl, and let it sit for 6–24 hours. The spores will drop onto the surface, creating a print.

The success rate varies depending on factors like sterility, substrate quality, and mushroom species. With proper technique, success rates can range from 50% to 90%, but contamination is a common challenge.

The process can take 2–6 months, depending on the species and growing conditions. Spore-to-fruiting stages involve inoculation, colonization, and fruiting, each requiring time and specific environmental conditions.