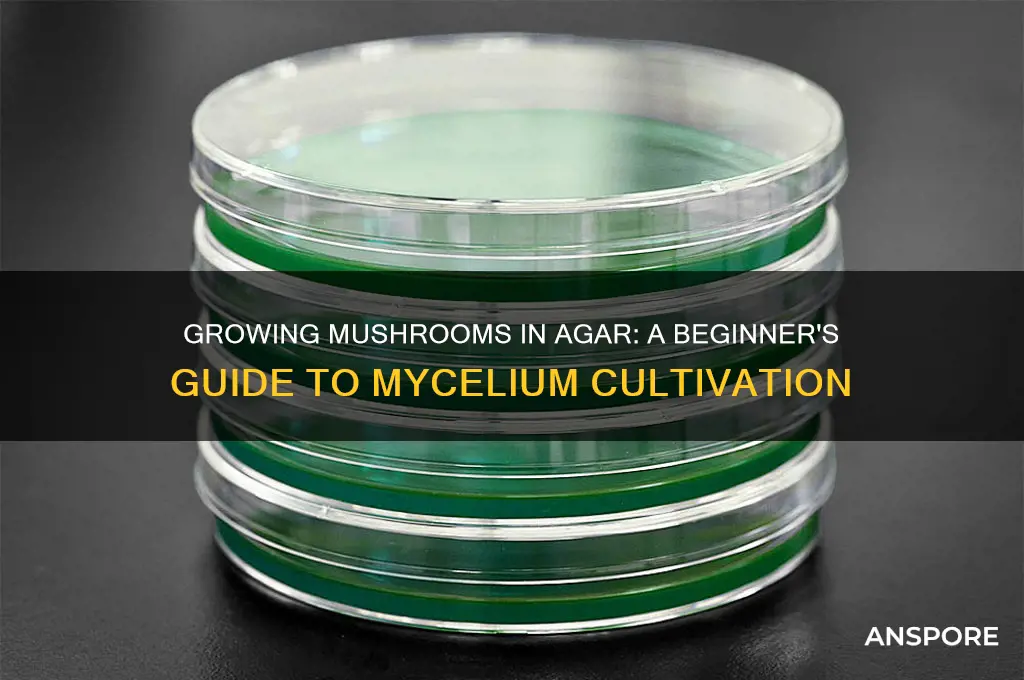

Growing mushrooms in agar is a fascinating and increasingly popular technique used by both hobbyists and professionals in mycology. Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, serves as an ideal medium for cultivating mushroom mycelium due to its nutrient-rich composition and sterile environment. This method allows for the isolation and propagation of specific mushroom strains, making it a cornerstone in mushroom cultivation and research. By introducing mushroom spores or tissue samples to agar plates, growers can observe mycelial growth, study fungal behavior, and produce pure cultures for transfer to more substantial substrates like grain or soil. Whether for scientific study, gourmet mushroom production, or simply exploring the wonders of fungi, agar provides a reliable and controlled platform for nurturing mushrooms from their earliest stages.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Possible | Yes, mushrooms can be grown in agar. |

| Purpose | Agar is commonly used for mushroom tissue culture, spawn production, and research. |

| Agar Type | Typically, potato dextrose agar (PDA) or malt extract agar (MEA) is used. |

| Sterility | Agar must be sterilized (autoclaving at 121°C for 15-20 minutes) to prevent contamination. |

| Inoculation | Mushroom mycelium or spores are introduced into the agar under sterile conditions. |

| Incubation | Agar plates are incubated at optimal temperatures (20-28°C) for mycelial growth. |

| Growth Time | Mycelium typically colonizes the agar within 7-14 days, depending on the species. |

| Contamination Risk | High if sterile techniques are not followed; bacteria, molds, and other fungi can outcompete mushroom mycelium. |

| Applications | Used for cloning, strain preservation, and producing grain spawn for fruiting mushrooms. |

| Limitations | Agar is not suitable for direct fruiting; mycelium must be transferred to a bulk substrate for mushroom production. |

| Cost | Relatively low-cost method for small-scale cultivation and experimentation. |

| Skill Level | Requires basic knowledge of sterile techniques and microbiology. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Agar Preparation Techniques: Sterilize agar properly to prevent contamination for successful mushroom mycelium growth

- Mycelium Inoculation Methods: Use sterile tools to transfer mycelium onto agar plates effectively

- Optimal Growth Conditions: Maintain temperature, humidity, and light levels for healthy mycelium development

- Contamination Prevention Tips: Keep workspace clean and use antiseptic solutions to avoid mold or bacteria

- Transferring to Substrate: Move mycelium from agar to bulk substrate for fruiting mushroom bodies

Agar Preparation Techniques: Sterilize agar properly to prevent contamination for successful mushroom mycelium growth

Growing mushrooms in agar requires a sterile environment to prevent contamination, and the agar itself is the first line of defense. Improperly sterilized agar can introduce bacteria, mold, or other microorganisms that compete with or kill the mushroom mycelium. Autoclaving is the gold standard for sterilization, using steam under pressure (15 psi at 121°C for 15–30 minutes) to eliminate all viable organisms. This method ensures the agar is free from contaminants while preserving its gel-like consistency, which is crucial for mycelium growth. Always use a reliable autoclave and verify its functionality with a spore test before use.

While autoclaving is ideal, alternative methods like pressure cooking can be used for home cultivators without access to lab equipment. A pressure cooker set at 15 psi for 45–60 minutes achieves similar results, though consistency may vary. For smaller batches, boiling agar in a covered pot for 30 minutes can reduce contamination risk, but it’s less reliable than autoclaving. Regardless of the method, allow the agar to cool to around 50°C before pouring it into sterile Petri dishes or containers to avoid damaging the mycelium or introducing airborne contaminants.

Contamination often occurs during the pouring and handling of agar, so maintaining a sterile workflow is critical. Work in a clean, draft-free area, and use a laminar flow hood or still-air box if available. Sterilize all tools, such as spatulas and Petri dishes, with 70% isopropyl alcohol or a flame. Pour the agar quickly but carefully to minimize exposure to the environment, and seal containers immediately after filling. Label each container with the date and agar type to track sterilization batches and identify potential issues later.

Even with proper sterilization, contamination can still occur, so vigilance is key. Inspect agar plates daily for signs of mold, discoloration, or unusual textures, which indicate contamination. If contamination is detected, discard the affected plates immediately to prevent spreading. For long-term storage, keep agar plates at 4°C in a refrigerator, but use them within 2–3 weeks for optimal results. Properly sterilized and handled agar not only supports healthy mycelium growth but also reduces the need for repeated sterilization attempts, saving time and resources in the cultivation process.

Do Shiitake Mushrooms Spoil? Shelf Life and Storage Tips

You may want to see also

Mycelium Inoculation Methods: Use sterile tools to transfer mycelium onto agar plates effectively

Growing mushrooms in agar begins with successful mycelium inoculation, a delicate process that hinges on sterility and precision. Sterile tools are non-negotiable; even a single contaminant can derail weeks of work. Autoclaving your instruments—such as scalpels, inoculation loops, or needles—at 121°C (250°F) for 15–20 minutes ensures they are free from bacteria, fungi, and spores. Alternatively, flaming metal tools with an alcohol lamp or sterile ethanol can provide a quick, effective sterilization for immediate use. Always work in a clean environment, ideally a still air box or laminar flow hood, to minimize airborne contaminants during the transfer process.

The inoculation technique itself requires a steady hand and careful planning. Start by preparing your agar plates—typically Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or Malt Extract Agar (MEA)—and allowing them to cool but not solidify completely. Using a sterile tool, carefully scrape a small piece of mycelium (roughly the size of a grain of rice) from your source culture. Gently press this fragment onto the agar surface, ensuring it adheres without disturbing the medium. For liquid cultures, use a sterile pipette to transfer 1–2 drops of mycelium suspension onto the agar. Seal the plate with parafilm or surgical tape immediately to prevent contamination, and incubate at 22–26°C (72–78°F) in darkness.

Comparing inoculation methods reveals trade-offs between simplicity and success rates. Beginners often prefer tissue culture transfers due to their forgiving nature, as larger mycelium fragments increase the likelihood of colonization. Advanced cultivators might opt for spore inoculation, which offers genetic diversity but requires more time and precision. Liquid culture transfers are efficient for scaling up projects but demand meticulous sterilization to avoid cross-contamination. Each method has its place, depending on your goals, resources, and experience level.

A critical caution: contamination is the silent saboteur of mycelium inoculation. Common culprits include unsterilized tools, unclean workspaces, and improper sealing of agar plates. Even a single bacterial colony or mold spore can outcompete your mycelium, rendering the plate unusable. To mitigate this, adopt a ritualistic approach to sterility—clean your workspace with 70% isopropyl alcohol, wear gloves, and limit exposure of plates to open air. Regularly inspect incubating plates for signs of contamination, such as discoloration or unusual growth patterns, and discard any compromised samples promptly.

In conclusion, mastering mycelium inoculation onto agar plates is a blend of art and science. Sterile tools, precise technique, and a meticulous mindset are your greatest allies. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional, understanding the nuances of each method and adhering to strict sterility protocols will significantly increase your chances of success. With practice, you’ll transform agar plates into thriving mycelium colonies, the first step in cultivating mushrooms with precision and purpose.

Raw Beets and Mushrooms: Safe to Eat Uncooked or Not?

You may want to see also

Optimal Growth Conditions: Maintain temperature, humidity, and light levels for healthy mycelium development

Growing mushrooms in agar requires precise control over environmental factors to ensure healthy mycelium development. Temperature is the cornerstone of this process, with most mushroom species thriving between 70°F and 75°F (21°C and 24°C). Deviations outside this range can stunt growth or encourage contamination. For example, temperatures below 60°F (15°C) slow metabolic activity, while those above 80°F (27°C) may stress the mycelium or promote bacterial growth. Use a digital thermometer to monitor conditions, and consider a heating mat or incubator for consistent warmth, especially in cooler climates.

Humidity is equally critical, as mycelium requires moisture to expand and absorb nutrients from the agar. Aim for a relative humidity of 90–95% within the growing environment. This can be achieved by placing the agar plates in a sealed container with a humidifier or damp paper towels. However, excessive moisture can lead to condensation, which increases the risk of mold or bacterial contamination. To mitigate this, ensure proper air circulation by slightly cracking the container lid or using a small fan on low speed.

Light plays a subtle yet significant role in mycelium development. While mushrooms do not require light for photosynthesis, indirect, low-intensity light can stimulate growth and guide the direction of mycelial expansion. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can overheat the agar and dry out the mycelium. A 12-hour photoperiod with cool white LED lights is ideal for most species. For example, *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms) respond well to this light cycle, while *Ganoderma lucidum* (reishi) may require slightly less exposure.

Maintaining these conditions requires vigilance and adaptability. Regularly inspect agar plates for signs of contamination, such as discoloration or unusual textures, and discard any compromised samples immediately. For long-term projects, document temperature, humidity, and light levels daily to identify patterns and adjust as needed. While the process demands attention to detail, the reward of healthy, robust mycelium makes the effort worthwhile. With the right conditions, agar becomes a powerful tool for cultivating mushrooms, whether for research, culinary use, or mycological exploration.

Reviving Dehydrated Mushrooms: Can You Grow Fresh Fungi from Dried Caps?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Contamination Prevention Tips: Keep workspace clean and use antiseptic solutions to avoid mold or bacteria

Growing mushrooms in agar is a delicate process where contamination can swiftly derail your efforts. Even a single mold spore or bacterium can outcompete your mycelium, turning your petri dish into a battleground. The key to success lies in meticulous contamination prevention, starting with a pristine workspace. Imagine your lab as a surgical theater: every surface must be spotless. Use a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution to wipe down all surfaces, including your hands, tools, and the agar plates themselves. This concentration is effective against most pathogens without leaving harmful residues. For added protection, consider a 10% bleach solution for non-porous surfaces, but rinse thoroughly to avoid chemical contamination.

Antiseptic solutions are your second line of defense, but their application requires precision. Flame sterilization, using a Bunsen burner or alcohol lamp, is ideal for metal tools like inoculation loops and scalpels. Hold the tool in the flame until it glows red, ensuring all microorganisms are incinerated. For items that cannot withstand heat, such as gloves or plastic containers, a 70% ethanol spray is effective. However, avoid oversaturating, as excess liquid can introduce moisture that fosters bacterial growth. Always work in a laminar flow hood if available, as it creates a sterile air current that deflects contaminants away from your workspace.

The timing of your cleaning routine is as critical as the method. Sterilize your workspace and tools immediately before use, not hours in advance. Contaminants can resettle quickly, especially in environments with poor air quality. If you’re working in a home setup, consider using a HEPA filter to reduce airborne particles. Additionally, wear a mask and nitrile gloves to minimize shedding skin cells and respiratory droplets, which are common vectors for mold and bacteria. Even the slightest oversight, like touching your face or using a dirty pipette, can introduce contaminants that thrive in nutrient-rich agar.

A comparative analysis of contamination sources reveals that human error is often the culprit. For instance, opening agar plates too frequently or for too long exposes them to airborne spores. To mitigate this, practice efficient, deliberate movements during inoculation, minimizing the time plates are uncovered. Another common mistake is reusing materials without proper sterilization. While cost-effective, this practice is risky; always autoclave reusable items like glassware at 121°C for 15 minutes to ensure complete sterilization. Disposable items, though pricier, eliminate this risk entirely and are recommended for beginners.

Finally, adopt a mindset of vigilance. Contamination prevention is not a one-time task but a continuous process. Regularly inspect your workspace for signs of mold or bacterial growth, even in areas you think are sterile. Keep a log of your sterilization procedures and any deviations from protocol, as this can help identify the source of contamination if it occurs. Remember, growing mushrooms in agar is as much an art as it is a science. By treating your workspace with the care of a surgeon and the precision of a chemist, you’ll create an environment where mycelium can thrive—and contaminants cannot.

Exploring the Duration of a Mushroom Trip: What to Expect

You may want to see also

Transferring to Substrate: Move mycelium from agar to bulk substrate for fruiting mushroom bodies

Growing mushrooms on agar is a fascinating process, but the real magic happens when you transfer the mycelium to a bulk substrate. This step is crucial for fruiting mushroom bodies, as agar alone lacks the nutrients and structure needed for full development. The transition from sterile agar to a nutrient-rich substrate like straw, wood chips, or compost marks the shift from colonization to fruiting, where mushrooms finally emerge.

Steps for Transferring Mycelium to Substrate

Begin by preparing your bulk substrate according to the mushroom species’ requirements. For example, oyster mushrooms thrive on pasteurized straw, while shiitake prefer supplemented sawdust. Sterilize or pasteurize the substrate to eliminate competitors, ensuring the mycelium has a head start. Once cooled, introduce the mycelium by breaking the agar into small pieces and mixing it evenly into the substrate. Aim for a 1:10 ratio of agar to substrate to avoid overcrowding. Seal the mixture in a grow bag or container, maintaining humidity and darkness to encourage colonization.

Cautions to Consider

Contamination is the primary risk during this phase. Work in a clean environment, using gloves and a face mask to minimize airborne particles. Avoid overhandling the substrate, as this can introduce pathogens. Monitor the temperature, ideally keeping it between 70–75°F (21–24°C), as extremes can stress the mycelium or encourage mold. If you notice green or black spots, isolate the contaminated area immediately to prevent spread.

Practical Tips for Success

Patience is key—colonization can take 2–4 weeks, depending on the species and substrate. Once fully colonized, introduce fruiting conditions by exposing the substrate to light, reducing humidity slightly, and maintaining cooler temperatures (55–65°F or 13–18°C). Mist the surface regularly to simulate rainfall, which triggers pinhead formation. For species like lion’s mane, consider using a humidifier to maintain 80–90% humidity. Harvest mushrooms when the caps flatten or begin to drop spores to ensure optimal flavor and texture.

Transferring mycelium from agar to substrate is a pivotal step in mushroom cultivation, bridging the gap between sterile lab conditions and natural fruiting. By following precise steps, exercising caution, and applying practical tips, you can successfully grow mushrooms at home. This process not only yields fresh, edible fungi but also deepens your understanding of mycology, making it a rewarding endeavor for both hobbyists and enthusiasts.

Are Old Psilocybin Mushrooms Safe to Eat? Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, agar is a common medium used to cultivate mushroom mycelium, which can then be transferred to a substrate for fruiting.

Malt extract agar or potato dextrose agar are commonly used due to their nutrient content and ability to support mycelium growth.

Mycelium growth on agar typically takes 1-3 weeks, but fruiting bodies develop after transferring to a substrate, which can take an additional 2-6 weeks depending on the species.

No, agar plates should not be reused as they may become contaminated or depleted of nutrients, risking the health of the mycelium.