Harvesting mycelium from a dried mushroom is a topic of interest for both mycologists and enthusiasts, as mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus consisting of a network of fine white filaments—plays a crucial role in fungal growth and reproduction. While dried mushrooms primarily consist of the fruiting body, the mycelium is typically found in the substrate where the mushroom grew. Extracting viable mycelium from a dried mushroom can be challenging, as the drying process often damages or kills the delicate mycelial cells. However, some methods, such as rehydrating the mushroom and culturing it in a nutrient-rich medium, may allow for the regeneration of mycelium under optimal conditions. Success depends on factors like the mushroom species, the extent of drying, and the techniques used for rehydration and cultivation. This process is particularly relevant in mushroom cultivation, where mycelium is essential for producing new fruiting bodies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | Limited; mycelium is primarily found in living mushroom tissue, not in dried mushrooms. |

| Mycelium Presence in Dried Mushrooms | Minimal to none; drying preserves fruiting bodies but does not retain viable mycelium. |

| Purpose of Harvesting | Not practical for cultivation or propagation due to lack of viable mycelium. |

| Alternative Sources | Fresh mushrooms, mycelium cultures, or mycelium-based products (e.g., grow kits). |

| Potential Uses of Dried Mushrooms | Culinary, medicinal, or decorative purposes, not for mycelium extraction. |

| Scientific Studies | No recent studies support viable mycelium extraction from dried mushrooms. |

| Conclusion | Dried mushrooms are not a reliable source for harvesting mycelium. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mycelium viability in dried mushrooms

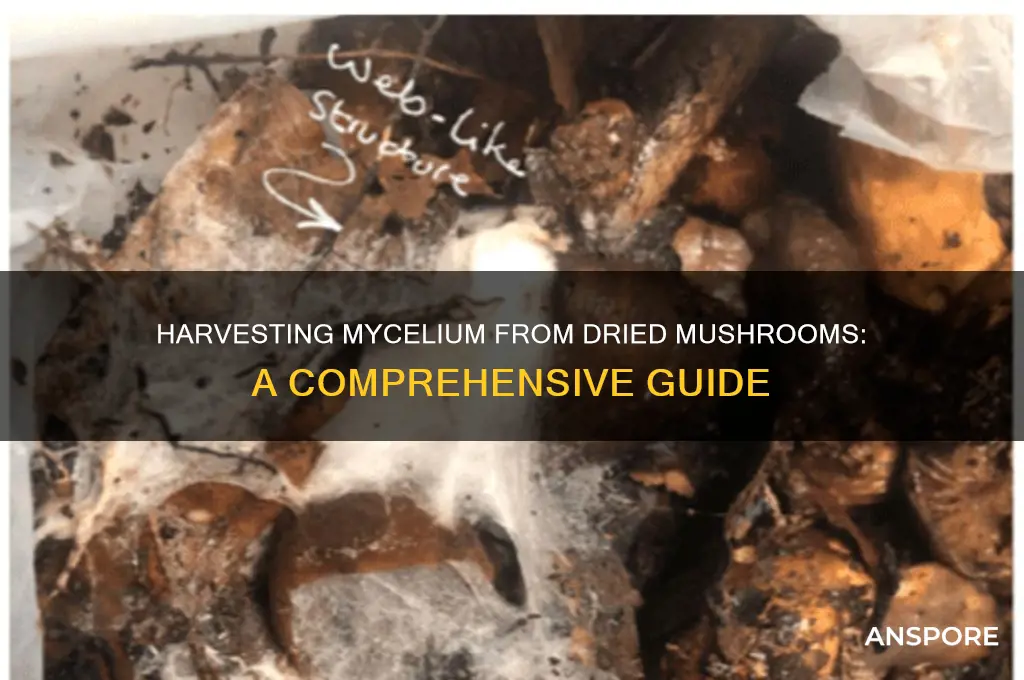

Dried mushrooms, often prized for their concentrated flavors and extended shelf life, also harbor a hidden potential: their mycelium. Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus consisting of a network of fine white filaments, is the engine behind mushroom growth. But does this vital network remain viable within a dried mushroom? The answer lies in understanding the delicate balance between desiccation and cellular resilience.

Drying mushrooms significantly reduces their moisture content, a process that typically halts biological activity. However, mycelium, being remarkably resilient, can enter a dormant state under such conditions. This dormancy is not death; it's a survival mechanism. Studies suggest that mycelium can remain viable in dried mushrooms for months, even years, depending on factors like drying method, storage conditions, and the mushroom species.

To assess mycelium viability, one can employ simple techniques. Rehydrating dried mushrooms in sterile water and observing for signs of growth, such as mycelial threading or primordia formation, is a common approach. However, this method may not always be conclusive, as some mycelium may be damaged during the drying process. More advanced techniques, like staining with vital dyes or molecular methods, can provide a more accurate assessment of cellular integrity.

It's crucial to note that not all dried mushrooms are created equal in terms of mycelium viability. Mushrooms dried at high temperatures or for extended periods are less likely to retain viable mycelium. Conversely, those dried at lower temperatures and for shorter durations have a higher chance of preserving mycelial vitality. Additionally, certain mushroom species are naturally more resilient to desiccation, making their mycelium more likely to survive the drying process.

For those interested in cultivating mushrooms from dried specimens, selecting high-quality, properly dried mushrooms is paramount. Look for mushrooms dried at temperatures below 40°C (104°F) and stored in airtight containers in a cool, dark place. When attempting to revive mycelium, start by rehydrating the mushrooms in sterile water at room temperature for 24-48 hours. If viable mycelium is present, you may observe white, thread-like growth within a few days. This revived mycelium can then be transferred to a suitable substrate, such as grain or sawdust, to initiate a new mushroom cultivation cycle.

In conclusion, while drying mushrooms may seem like a process that halts all biological activity, mycelium's remarkable resilience allows it to persist in a dormant state. By understanding the factors influencing mycelium viability and employing appropriate techniques, it is indeed possible to harvest and revive mycelium from dried mushrooms, opening up new possibilities for mushroom cultivation and research.

Discover Mushroom Locations in Disney Dreamlight Valley: A Guide

You may want to see also

Methods to extract mycelium from dried caps

Dried mushroom caps, often discarded after use, can still harbor viable mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus. Extracting mycelium from these caps allows for further cultivation, experimentation, or study. The process, while delicate, leverages the resilience of mycelial networks even in desiccated states. Success hinges on rehydration techniques, sterile conditions, and patience, as the mycelium slowly reactivates from its dormant state.

Rehydration and Isolation: Begin by rehydrating the dried caps in sterile water or a nutrient-rich solution, such as a diluted starch or sugar mixture, for 24–48 hours. This step awakens the dormant mycelium, encouraging it to resume growth. After rehydration, carefully excise the inner tissue of the cap using a sterilized scalpel or blade. This tissue, rich in mycelial fragments, serves as the inoculum for further cultivation. Transfer the excised tissue to a sterile agar plate or liquid culture medium, ensuring minimal contamination.

Direct Transfer to Substrate: For a more hands-on approach, skip the agar step and directly inoculate a sterile substrate, such as pasteurized grain or sawdust, with the rehydrated cap tissue. This method mimics natural conditions, allowing the mycelium to colonize the substrate as it would in the wild. Maintain a humid, warm environment (22–26°C) to support growth. Regularly inspect for contamination, as the open transfer increases exposure to airborne pathogens.

Liquid Culture Extraction: Advanced cultivators may opt for liquid culture extraction, which involves blending the rehydrated caps in sterile water to create a slurry. Filter the slurry through a fine mesh to remove large particulate matter, then transfer the liquid to a sterile container. Introduce a small amount of this liquid to a nutrient-rich broth, such as malt extract or potato dextrose, and incubate at 24–26°C with gentle agitation. This method promotes rapid mycelial growth, ideal for large-scale cultivation or research.

Cautions and Considerations: Sterility is paramount throughout the extraction process. Use a laminar flow hood or still air box to minimize contamination. Autoclave all tools and containers before use, and handle materials with sterilized gloves. Be mindful of the mushroom species, as some mycelium may require specific nutrients or conditions to thrive. Lastly, exercise patience; mycelial growth from dried caps can take weeks, depending on the species and method employed.

By employing these methods, enthusiasts and researchers alike can unlock the potential of dried mushroom caps, transforming them from waste into a valuable resource for cultivation and study. Each technique offers unique advantages, catering to different needs and skill levels, while highlighting the remarkable adaptability of mycelium.

Finding Brown Mushrooms in the Nether: Myth or Reality?

You may want to see also

Rehydration techniques for dried mushroom tissue

Dried mushrooms are a convenient way to preserve fungal material, but rehydrating them effectively is crucial for reviving their texture, flavor, and potential biological activity. The process begins with selecting the right liquid—water, broth, or even alcohol—depending on the intended use. For culinary purposes, warm water is the most common choice, as it gently rehydrates the mushroom tissue without altering its taste significantly. However, for mycelium cultivation, sterile distilled water or nutrient-rich solutions like malt extract broth are preferred to encourage growth. The key is to avoid overheating, as temperatures above 60°C (140°F) can denature proteins and damage cellular structures.

Rehydration time varies based on the mushroom species and drying method. Thin-capped varieties like oyster mushrooms typically rehydrate within 15–20 minutes, while denser species like porcini may require up to an hour. A practical tip is to use a glass or ceramic container to prevent chemical leaching from plastics or metals. For mycelium harvesting, the rehydration liquid should be filtered after soaking to separate the mushroom tissue from the mycelial network, which often begins to grow within 24–48 hours under sterile conditions. This step is critical for isolating viable mycelium for further cultivation.

One lesser-known technique involves using a vacuum chamber to accelerate rehydration. By removing air from the container, the pressure differential forces liquid into the mushroom tissue more rapidly, reducing rehydration time by up to 50%. This method is particularly useful for large-scale operations or time-sensitive experiments. However, it requires specialized equipment and careful monitoring to avoid damaging the delicate fungal structures. For home cultivators, a simple soak in a sealed container at room temperature remains the most accessible and reliable approach.

Caution must be exercised when rehydrating mushrooms for consumption or cultivation. Contamination is a significant risk, especially when using non-sterile liquids or containers. Always inspect dried mushrooms for signs of mold or discoloration before rehydrating, and discard any questionable material. For mycelium harvesting, sterilize all tools and containers using autoclaving or alcohol wipes to maintain a clean environment. Proper rehydration not only restores the mushroom’s qualities but also serves as a foundation for successful mycelium propagation, bridging the gap between preservation and regeneration.

Mushrooms and Madness: Unraveling the Truth Behind Psychedelic Effects

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tools needed for mycelium harvesting

Harvesting mycelium from dried mushrooms requires precision and the right tools to ensure success. The process begins with rehydrating the mushroom, which reactivates the mycelium. A sterile container, such as a glass jar or petri dish, is essential to prevent contamination during this step. Distilled water, heated to near-boiling, is ideal for rehydration, as it minimizes the risk of introducing unwanted microorganisms. A spray bottle can be used to gently mist the mushroom, ensuring even moisture distribution without oversaturating it. This initial setup is critical, as mycelium is highly sensitive to its environment.

Once rehydrated, the mycelium must be carefully extracted. A scalpel or sterile blade is indispensable for this task, allowing you to delicately slice away the mushroom’s fruiting body and expose the mycelium network. Tweezers, preferably stainless steel and sterilized with alcohol, are useful for handling the fragile mycelium without damaging it. A magnifying glass or microscope can aid in identifying healthy mycelium strands, ensuring you’re harvesting viable material. These tools, when used correctly, transform a complex process into a manageable task.

Sterilization is non-negotiable in mycelium harvesting. An autoclave or pressure cooker is necessary to sterilize substrates like agar or grain, which will serve as the mycelium’s new growth medium. If these tools are unavailable, a DIY approach involves using a large pot with a tight-fitting lid to create a makeshift sterilization chamber. Isopropyl alcohol (70% concentration) and a flame source, such as a kitchen torch, are essential for sterilizing tools and work surfaces. Even a minor oversight in sterilization can lead to contamination, rendering the harvested mycelium unusable.

For long-term storage or propagation, additional tools come into play. A laminar flow hood, while expensive, provides a sterile environment for transferring mycelium to new substrates. Alternatively, a still-air box—a simple, sealed container with gloves attached—can be constructed for a fraction of the cost. Vacuum-sealed bags or glass vials are ideal for storing mycelium, preserving its viability for months or even years. Labeling tools, such as a permanent marker and adhesive labels, are often overlooked but crucial for tracking harvest dates and strain information.

Finally, patience and observation are intangible yet vital tools in this process. Mycelium growth is slow, and regular monitoring with a notebook or digital log helps track progress and identify issues early. A thermometer and hygrometer can ensure optimal temperature (22–26°C) and humidity (60–70%) levels, fostering healthy mycelium development. While the physical tools are essential, the meticulous attention to detail separates successful harvests from failed attempts. With the right equipment and mindset, harvesting mycelium from dried mushrooms becomes a rewarding endeavor.

Freezing Spinach and Artichoke Stuffed Mushrooms: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Storing harvested mycelium for future use

Harvesting mycelium from dried mushrooms is indeed possible, but the viability of the mycelium depends on how the mushrooms were dried and stored. Proper storage of harvested mycelium is critical to preserving its vitality for future use, whether for cultivation, research, or medicinal purposes. Mycelium is a living organism, and its longevity hinges on maintaining optimal conditions that mimic its natural environment while preventing contamination.

Steps for Storing Harvested Mycelium

Begin by transferring the harvested mycelium into a sterile container, such as a glass jar or a vacuum-sealed bag. Ensure the container is airtight to prevent exposure to airborne contaminants. For short-term storage (up to 6 months), refrigerate the mycelium at temperatures between 2°C and 4°C. This slows metabolic activity without freezing the cells. For long-term storage (beyond 6 months), consider freezing the mycelium at -20°C, though this method may reduce viability slightly. Before freezing, suspend the mycelium in a protective medium like glycerol (final concentration of 10–15%) to prevent cell damage from ice crystals.

Cautions to Consider

Avoid storing mycelium in environments with fluctuating temperatures or humidity, as these conditions can stress the organism and reduce its viability. Contamination is the greatest risk during storage, so always use sterile techniques when handling mycelium. Even a small amount of mold or bacteria can outcompete the mycelium, rendering it unusable. Additionally, do not store mycelium in direct sunlight or near heat sources, as this can dehydrate or kill the cells.

Practical Tips for Optimal Storage

Label containers with the date of storage and the mushroom species to track viability over time. For medicinal or research purposes, periodically test stored mycelium for viability by inoculating a small sample into a sterile growth medium. If using dried mushrooms as a source, rehydrate them in sterile water before attempting to harvest mycelium, as this increases the chances of successful extraction. For hobbyists, consider storing mycelium in agar plates, which provide a stable, nutrient-rich environment for extended periods.

Storing harvested mycelium effectively requires attention to detail and adherence to sterile practices. By following these steps and precautions, you can preserve mycelium for months or even years, ensuring it remains viable for future projects. Whether you're a cultivator, researcher, or enthusiast, proper storage is the key to unlocking the full potential of this remarkable organism.

Reheating Garlic Mushrooms: Tips for Perfect Flavor and Texture

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, you cannot harvest viable mycelium from a fully dried mushroom. The drying process kills the mycelium, making it unusable for cultivation or propagation.

No, dried mushrooms do not retain living mycelium. To grow mushrooms, you need living mycelium from a fresh mushroom or a mycelium culture.

No, dried mushrooms are not suitable for starting a mycelium culture. You would need fresh mushroom tissue or a pre-existing mycelium culture to initiate growth.