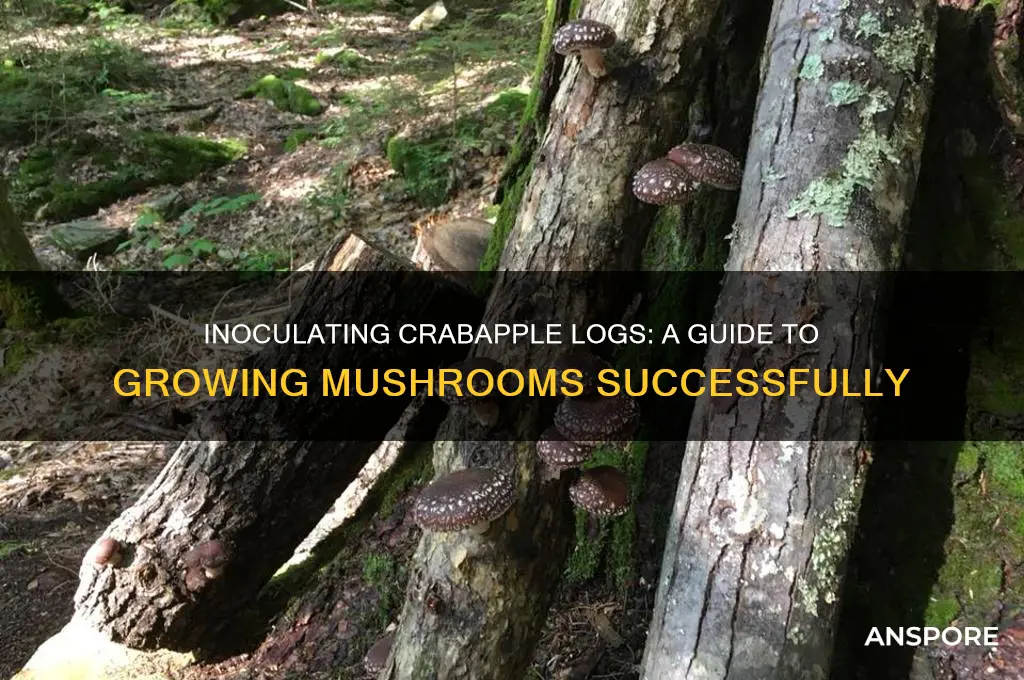

Inoculating a crabapple log with mushrooms is a fascinating practice that combines mycology and sustainable gardening, allowing enthusiasts to cultivate edible or medicinal fungi directly on wood. Crabapple logs, rich in nutrients and with a dense structure, provide an ideal substrate for mushroom mycelium to colonize and fruit. The process involves drilling holes into the log, inserting mushroom spawn, and sealing it to retain moisture, creating a mini-ecosystem where the fungi can thrive. This method not only offers a unique way to grow mushrooms but also repurposes wood that might otherwise go to waste, fostering a deeper connection to nature and self-sufficiency. Whether for culinary, medicinal, or ecological purposes, inoculating crabapple logs with mushrooms is both a rewarding and environmentally conscious endeavor.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Host Tree | Crabapple (Malus spp.) |

| Mushroom Species Compatibility | Shiitake (Lentinula edodes), Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus), Oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus), and others |

| Inoculation Method | Drill and plug, sawdust spawn, or dowel spawn |

| Best Time for Inoculation | Late winter to early spring (dormant season) |

| Log Preparation | Freshly cut (within 2-4 weeks), debarked, and sealed ends |

| Log Diameter | 4-8 inches (10-20 cm) for optimal fruiting |

| Log Length | 3-4 feet (1-1.2 meters) |

| Inoculation Density | 1-2 plugs or dowels per foot of log length |

| Colonization Time | 6-18 months, depending on species and conditions |

| Fruiting Conditions | High humidity (85-95%), cool temperatures (50-70°F or 10-21°C), and shade |

| Fruiting Frequency | Multiple flushes per year for 3-5 years |

| Success Rate | High with proper species selection and care |

| Pest and Disease Management | Monitor for competitors (e.g., mold) and pests (e.g., slugs) |

| Harvesting | Pick mushrooms when caps are fully open but before spores drop |

| Environmental Impact | Sustainable practice, supports local ecosystems |

| Legal Considerations | Check local regulations for foraging and cultivation |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Choosing compatible mushroom species for crabapple wood

Crabapple wood, with its dense grain and natural sugars, offers a promising substrate for mushroom cultivation. However, not all mushroom species thrive on this wood. Compatibility depends on factors like wood hardness, nutrient content, and the mushroom’s mycelial preferences. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are known to colonize hardwoods efficiently, making them a strong candidate for crabapple logs. In contrast, species like shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) may struggle due to crabapple’s lower lignin content compared to oak or maple. Selecting the right species ensures successful inoculation and a bountiful harvest.

When choosing a mushroom species, consider the wood’s moisture retention and decay resistance. Crabapple wood tends to dry out faster than softer woods, so species like lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*)—which prefers drier conditions—may perform better. Inoculation timing is critical; spring is ideal, as the wood is still moist from winter, and temperatures support mycelial growth. Use a drill bit slightly larger than your spawn plugs (typically 5/16 inch) to create holes every 4–6 inches along the log. Seal the plugs with wax to retain moisture and prevent contamination.

A comparative analysis of crabapple wood versus other hardwoods reveals its unique challenges. While oak and beech are traditional choices for shiitake, crabapple’s denser structure can hinder colonization. However, it excels for species like reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*), which prefers harder substrates. Experimenting with mixed cultures, such as combining oyster and reishi, can maximize log utilization. Monitor logs for signs of contamination, such as green or black mold, and isolate affected logs to protect the rest of your crop.

Persuasively, crabapple wood’s availability and unique properties make it an underutilized resource for mushroom cultivation. Its natural resistance to rot, coupled with proper species selection, can yield high-quality mushrooms with distinct flavors. For example, crabapple-grown oysters often have a sweeter, nuttier taste due to the wood’s sugar content. To enhance success, pre-soak logs in water for 24–48 hours before inoculation to increase moisture levels. Store logs in a shaded, humid area, and expect fruiting within 6–12 months, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

In conclusion, choosing compatible mushroom species for crabapple wood requires understanding both the wood’s characteristics and the fungi’s needs. Start with hardy species like oyster or lion’s mane, and experiment with others like reishi or even wine cap (*Stropharia rugosoannulata*) for outdoor beds. Proper inoculation techniques, combined with patience and observation, will transform crabapple logs into productive mushroom farms. With the right approach, this overlooked wood can become a valuable asset for any mycologist or hobbyist.

Can You Eat Lung Oyster Mushrooms? A Tasty Fungus Guide

You may want to see also

Preparing the crabapple log for inoculation

Crabapple logs, with their dense hardwood and natural sugars, offer an ideal substrate for mushroom inoculation. However, successful colonization depends on meticulous preparation. The first step is selecting a log that’s both healthy and freshly cut—ideally within 2–4 weeks of felling. This ensures the wood retains moisture while remaining free from competing fungi or insects. Logs should be at least 3–4 inches in diameter and 3–4 feet in length, providing ample space for mycelium growth without being overly cumbersome to handle.

Once the log is selected, cleaning and sanitizing it is critical. Use a stiff brush to remove loose bark, debris, and dirt, which can harbor contaminants. While some mycologists advocate for a light sanding to expose fresh wood, this step is optional. After cleaning, soak the log in cold water for 24–48 hours to saturate the wood fibers. This hydration process not only softens the log but also creates a favorable environment for mycelium penetration. Avoid using hot water, as it can cook the sugars and reduce the log’s nutritional value.

Drilling holes for inoculation requires precision. Use a 5/16-inch drill bit to create holes spaced 6–8 inches apart in a diamond pattern, ensuring even distribution. Drill to a depth of 1–1.5 inches, angling the holes slightly upward to prevent water pooling. After drilling, immediately insert the mushroom spawn—typically sawdust or plug spawn—into the holes. Tap gently with a mallet to secure the spawn, then seal each hole with wax to retain moisture and protect against contaminants.

The final step is creating an optimal environment for colonization. Store the inoculated log in a cool, shaded area with high humidity, such as a forest floor or under a shade cloth. Mist the log periodically to maintain moisture, but avoid overwatering, which can lead to mold. Patience is key; mycelium can take 6–12 months to fully colonize the log, depending on species and conditions. Regularly inspect the log for signs of contamination or pest activity, addressing issues promptly to ensure a successful harvest.

Can Dogs Safely Eat Portobello Mushrooms? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Drilling and filling holes with mushroom spawn

Drilling holes into a crabapple log to inoculate it with mushroom spawn is a precise art that blends forestry, mycology, and craftsmanship. The process begins with selecting a log that’s 3–6 inches in diameter, freshly cut (within 1–3 months) to ensure the wood is still nutrient-rich but not actively decaying. Using a 5/16-inch drill bit, bore holes 1–2 inches deep and spaced 6–8 inches apart in a diamond or staggered pattern. This spacing maximizes mycelial spread without overwhelming the log’s resources. The drill bit size is critical: too large, and the spawn may not colonize effectively; too small, and it restricts growth. Each hole should be slightly angled upward to prevent water pooling, which can lead to contamination.

Once drilled, the holes must be filled with mushroom spawn, typically sawdust or plug spawn, depending on the species. For oyster mushrooms, 1–2 tablespoons of sawdust spawn per hole suffices, while shiitake plugs (pre-inoculated wooden dowels) are tapped into the holes with a rubber mallet. After filling, seal each hole with melted cheese wax or a natural alternative like beeswax mixed with wood chips. This step is non-negotiable—it protects the spawn from drying out or being invaded by competing fungi. A single log can hold 20–30 holes, translating to 2–3 pounds of spawn, depending on the variety. Proper dosage ensures the mycelium colonizes the log without exhausting its energy reserves.

The success of this method hinges on environmental conditions post-inoculation. Crabapple logs thrive in partial shade, where humidity hovers around 60–70%. Stack logs off the ground on crisscrossed branches to promote air circulation and prevent rot. Mist the logs weekly during dry spells, but avoid oversaturating them. Colonization takes 6–12 months, during which the mycelium silently transforms the log into a living substrate. The first flush of mushrooms typically appears in the second year, with subsequent harvests possible for 3–5 years. Patience is paramount; rushing the process risks weak or nonexistent fruiting.

Comparing this technique to other inoculation methods, such as soaking logs in mushroom culture, drilling and filling offers greater control over spawn distribution and reduces the risk of contamination. However, it’s labor-intensive and requires precision. For beginners, starting with a small batch of logs (2–3) allows for experimentation without significant investment. Advanced growers might pair this method with totems (upright logs) or incorporate companion species like reishi, which thrive in crabapple’s dense grain. The key takeaway is that drilling and filling is not just a technique—it’s a commitment to nurturing a symbiotic relationship between wood and fungus.

Practical tips can elevate this process from functional to masterful. Pre-drill holes in a shaded area to avoid overheating the wood, and sterilize the drill bit with rubbing alcohol between logs to prevent cross-contamination. Label each log with the mushroom species and inoculation date using waterproof tags. For those in colder climates, insulate logs with straw bales during winter to protect the mycelium. Finally, document the colonization process with photos; this not only tracks progress but also helps troubleshoot issues like mold or pest infestations. With care and attention, a crabapple log becomes more than firewood—it transforms into a thriving mushroom farm.

Boiling Mushrooms Before Freezing: A Pre-Cooking Guide for Preservation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sealing and waxing the inoculated log properly

After inoculating a crabapple log with mushroom mycelium, sealing and waxing becomes a critical step to ensure the log’s longevity and the mycelium’s success. The primary purpose of this process is to retain moisture within the log while preventing contamination from competing molds or bacteria. Without proper sealing, the log can dry out, halting mycelial growth, or become a breeding ground for unwanted organisms. Waxing, in particular, creates a breathable yet protective barrier that allows gas exchange while locking in humidity—a delicate balance essential for mushroom cultivation.

The process begins with choosing the right materials. Food-grade cheese wax is the most commonly recommended option due to its low melting point (around 140°F or 60°C) and ease of application. Paraffin wax can also be used but requires higher temperatures, increasing the risk of damaging the mycelium. Melt the wax in a double boiler to avoid direct heat, which can cause overheating and fire hazards. For smaller logs, a wax-dip method works well, while larger logs may require brushing or pouring the wax evenly over the surface. Ensure all ends and cracks are thoroughly coated, as these are prime entry points for contaminants.

One common mistake is applying wax too soon after inoculation. The mycelium needs time to colonize the log, typically 2–4 weeks, depending on temperature and humidity. Premature waxing can trap excess moisture, leading to anaerobic conditions that stifle growth. Conversely, waiting too long increases the risk of contamination. Monitor the log for signs of mycelial activity, such as white fuzz or a musty scent, before sealing. Once waxed, the log should be stored in a shaded, humid environment (around 60–70% humidity) to encourage fruiting.

While sealing is crucial, it’s not without risks. Over-waxing can suffocate the mycelium, while under-waxing leaves the log vulnerable. A thin, even coat is ideal—aim for a translucent layer that allows the wood grain to show through. For added protection, some cultivators apply a layer of natural sealant, like melted beeswax mixed with a small amount of coconut oil, before the final wax coat. This blend enhances flexibility and reduces cracking as the log expands and contracts with moisture changes.

Finally, patience is key. After sealing, the log may take several months to produce mushrooms, depending on species and conditions. Resist the urge to disturb the log or add additional wax, as this can introduce contaminants. Regularly inspect for cracks or signs of mold, and reapply wax as needed. With proper sealing and care, a crabapple log can fruit for multiple years, making the meticulous process of waxing well worth the effort.

Discover the Best Places to Buy Dried Mushrooms Online & Locally

You may want to see also

Caring for the log during mushroom colonization

Inoculating a crabapple log with mushrooms transforms it into a living substrate, but successful colonization requires vigilant care. The log’s environment directly influences mycelium growth, and neglect can lead to contamination or stunted development. Key factors include moisture, temperature, and protection from pests. For instance, crabapple wood, being denser than alder or poplar, retains moisture differently, necessitating more frequent soaking during dry periods. A simple yet effective method is to submerge the log in water for 24 hours every 2–3 weeks, ensuring the wood absorbs enough moisture without becoming waterlogged.

Moisture management is both an art and a science. Too little, and the mycelium desiccates; too much, and mold or bacteria thrive. Use a spray bottle to mist the log’s surface weekly, maintaining humidity around 60–70%. Avoid overhead watering, as pooling water can suffocate the mycelium. Temperature plays a complementary role, with most mushroom species thriving between 55°F and 75°F (13°C–24°C). Keep the log in a shaded area, as direct sunlight raises temperatures and dries the wood too quickly. A north-facing spot under a tree canopy or a shaded corner of a shed works well.

Pest control is often overlooked but critical. Slugs, beetles, and wood-boring insects can damage the log and compete with mycelium for nutrients. Diatomaceous earth, applied sparingly around the log’s base, deters crawling pests without harming the mushrooms. For airborne threats, cover the log with a fine mesh screen, ensuring airflow isn’t restricted. Inspect the log monthly for signs of infestation or mold, addressing issues immediately with organic solutions like neem oil or physical removal.

Patience is paramount during colonization, which can take 6–18 months depending on species and conditions. Resist the urge to disturb the log, as mycelium is fragile and easily disrupted. Instead, monitor progress by tapping the log gently; a hollow sound indicates healthy mycelium consumption. If the log feels solid after a year, increase moisture and ensure optimal conditions. Once pins emerge, reduce watering to encourage fruiting, as mushrooms require drier conditions to develop.

Finally, consider the log’s long-term health. Crabapple wood, rich in tannins, can inhibit some mushroom species but is ideal for oyster or shiitake mushrooms. Rotate logs annually to prevent soil-borne pathogens from accumulating. After harvesting, replenish nutrients by drilling small holes and inserting compost or coffee grounds, which boost subsequent flushes. With consistent care, a single crabapple log can produce mushrooms for 3–5 years, turning a simple inoculation project into a sustainable harvest.

Can Genius Mushrooms Cause Unusual Sensations? Exploring Their Effects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can inoculate a crabapple log with mushrooms. Crabapple wood is suitable for mushroom cultivation, particularly for species like shiitake, oyster, and lion's mane, as it has a dense structure that retains moisture well.

The best time to inoculate a crabapple log is during late winter or early spring, when the tree is dormant and the wood is fresh. This timing allows the mycelium to establish itself before warmer temperatures stimulate growth.

To prepare a crabapple log, cut it to the desired length (typically 3-4 feet), debark the wood slightly, and drill holes for inoculation. Use a sterile tool to insert mushroom spawn into the holes, seal them with wax, and keep the log in a shaded, moist environment to encourage mycelium growth.

![Premium Mushroom Monotub [XLarge, 68Q Grow Kit] Portable and Compact Fruiting Chamber with Filter Discs, Liner and Adjustable Air Vents, 22.8 x 15.7” x 12”, Brown](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71lbmVd8wdL._AC_UL320_.jpg)