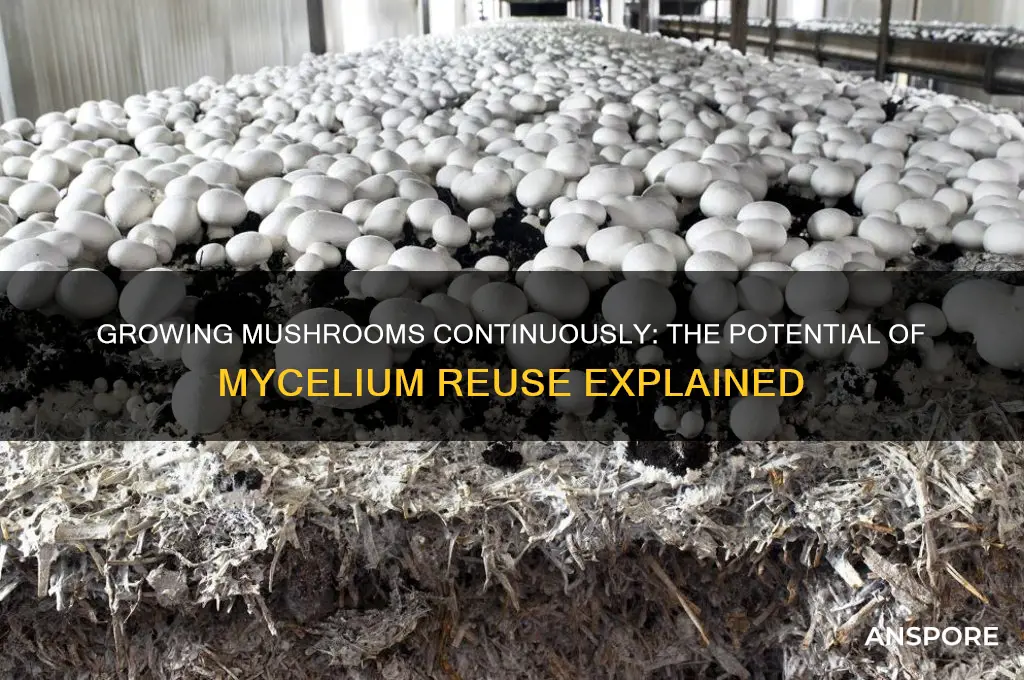

Growing mushrooms from mycelium is a fascinating and sustainable practice that allows enthusiasts and cultivators to continuously harvest mushrooms from a single source. Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, serves as the foundation for mushroom growth and can be cultivated in various substrates like straw, wood chips, or grain. Once established, mycelium can be maintained and reused, enabling repeated mushroom fruiting cycles. This method not only reduces waste but also offers a cost-effective way to produce fresh mushrooms at home or on a larger scale. However, success depends on proper care, including maintaining optimal conditions for humidity, temperature, and light, as well as preventing contamination. With the right techniques, mycelium can indeed be a renewable resource for growing mushrooms indefinitely.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reusability of Mycelium | Yes, mycelium can be reused for multiple mushroom growth cycles, depending on the species and conditions. |

| Lifespan of Mycelium | Varies by species; some mycelium can remain viable for months to years if properly stored and maintained. |

| Storage Conditions | Requires cool, dark, and sterile conditions to prevent contamination and maintain viability. |

| Growth Medium | Mycelium needs a suitable substrate (e.g., straw, wood chips, grain) to continue fruiting mushrooms. |

| Contamination Risk | High; mycelium is susceptible to mold, bacteria, and other contaminants if not handled properly. |

| Species Compatibility | Not all mushroom species can be regrown from mycelium; some are more resilient than others. |

| Yield Over Time | Yields may decrease with each successive flush as the mycelium exhausts nutrients in the substrate. |

| Techniques for Reuse | Includes transferring mycelium to fresh substrate, maintaining sterile techniques, and avoiding overexposure to air. |

| Commercial Viability | Widely used in commercial mushroom farming to maximize efficiency and reduce costs. |

| Home Cultivation | Possible for hobbyists with proper care, but requires attention to detail and cleanliness. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mycelium Lifespan and Reuse

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, is a resilient and versatile organism that can indeed be reused to grow mushrooms multiple times under the right conditions. Its lifespan varies depending on factors like species, environment, and care. For instance, oyster mushroom mycelium can remain viable for several months to a year when stored properly, while shiitake mycelium may last even longer, up to two years. Understanding this lifespan is crucial for maximizing productivity and minimizing waste in mushroom cultivation.

To reuse mycelium effectively, follow these steps: first, after harvesting mushrooms, allow the mycelium to rest for 1–2 weeks in a cool, dark place to recover. Second, transfer it to a fresh substrate, ensuring proper sterilization to prevent contamination. For example, mixing spent mycelium with fresh straw or sawdust can rejuvenate its growth potential. Third, maintain optimal conditions—temperature between 60–75°F (15–24°C) and humidity above 60%—to encourage new fruiting. This process can be repeated 2–3 times before the mycelium’s vigor diminishes.

However, reusing mycelium comes with cautions. Over time, its ability to produce mushrooms decreases due to genetic degradation or nutrient depletion. Contamination risks also rise with each reuse, as the mycelium becomes more susceptible to competing molds or bacteria. To mitigate this, always inspect the mycelium for signs of contamination before reuse and discard any discolored or foul-smelling portions. Additionally, avoid reusing mycelium more than three times to ensure consistent yields.

Comparatively, reusing mycelium is more sustainable than starting from spores or grain spawn each time. It reduces costs and minimizes waste, making it an attractive option for both hobbyists and commercial growers. For example, a small-scale grower can save up to 30% on substrate and spawn costs by reusing mycelium. However, this method requires careful monitoring and a deeper understanding of fungal biology to succeed.

In conclusion, mycelium’s lifespan and reuse potential offer a practical and eco-friendly approach to mushroom cultivation. By following specific steps, being mindful of limitations, and adopting a patient, observant mindset, growers can extend the productivity of their mycelium and enjoy multiple harvests from a single inoculation. This not only maximizes efficiency but also deepens the connection between cultivator and organism, highlighting the regenerative nature of fungi.

Mastering Oyster Mushrooms: Simple Cooking Techniques for Delicious Results

You may want to see also

Optimal Growing Conditions

Mushrooms thrive under specific environmental conditions, and mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus—is no exception. To keep growing mushrooms from mycelium, you must replicate the optimal conditions that mimic their natural habitat. Temperature is critical; most mushroom species flourish between 55°F and 75°F (13°C and 24°C). For example, oyster mushrooms prefer a slightly warmer range of 65°F to 75°F (18°C to 24°C), while shiitake mushrooms perform best between 55°F and 65°F (13°C to 18°C). Maintaining this range ensures the mycelium remains active and productive.

Humidity is another non-negotiable factor. Mushrooms require a high-humidity environment, typically between 80% and 95%, to prevent dehydration and encourage fruiting. A hygrometer can help monitor levels, and misting the growing area or using a humidifier can maintain optimal moisture. Substrates, such as straw, wood chips, or compost, must also retain moisture without becoming waterlogged. For instance, pasteurizing straw before inoculation with mycelium reduces competing organisms and ensures the substrate holds enough water for mushroom growth.

Light plays a subtle but important role in mushroom cultivation. While mycelium grows in darkness, mushrooms need indirect light to develop properly. A 12-hour light cycle with low-intensity LED or natural light is sufficient. Direct sunlight can dry out the substrate and harm the mycelium, so diffused light is ideal. For indoor growers, a simple timer-controlled lamp can provide the necessary light without disrupting the growing environment.

Air exchange is often overlooked but essential for healthy mushroom growth. Stagnant air can lead to mold or bacterial contamination, while excessive airflow can dry out the substrate. A balanced approach involves providing fresh air without causing drafts. Small vents or a passive airflow system can achieve this. For example, a grow tent with adjustable vents allows for controlled air exchange, ensuring the mycelium receives oxygen while maintaining humidity levels.

Finally, patience and observation are key to mastering optimal growing conditions. Mycelium can take weeks to colonize a substrate fully, and fruiting bodies may not appear until the environment is just right. Regularly inspect the growing area for signs of contamination or stress, such as discoloration or unusual odors. Adjusting conditions incrementally—like raising humidity by 5% or lowering temperature by 2°F—can help fine-tune the environment for maximum yield. With consistent care and attention to these specifics, you can keep growing mushrooms from mycelium indefinitely.

Testing Mushrooms: Methods, Safety, and Scientific Insights Explained

You may want to see also

Harvesting Without Damaging Mycelium

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, is the lifeblood of mushroom cultivation. Proper harvesting techniques ensure its longevity, allowing for multiple flushes of mushrooms. The key lies in minimizing disturbance to the mycelium network during harvest. Unlike annual plants, fungi are perennial, and their mycelium can continue producing mushrooms if treated with care. This delicate balance between harvesting and preservation is crucial for sustainable mushroom farming.

To harvest without damaging mycelium, start by identifying mature mushrooms ready for picking. Gently twist and pull the mushroom at its base, avoiding forceful tugging that could uproot the mycelium. Use a clean, sharp knife if necessary, but only as a last resort. Leave smaller, immature mushrooms to grow, as they will contribute to future flushes. After harvesting, avoid compacting the substrate, as this can suffocate the mycelium. Lightly mist the growing area to maintain humidity, but avoid overwatering, which can lead to contamination.

Comparing traditional farming methods to mushroom cultivation highlights the unique challenges of working with mycelium. While crops like tomatoes or carrots are harvested by uprooting the entire plant, mushrooms require a more nuanced approach. The mycelium remains in the substrate, continuing to grow and produce mushrooms. This regenerative nature makes fungi an efficient and sustainable crop, provided the mycelium is protected. For instance, a single brick of colonized substrate can yield multiple harvests over several months, far outpacing the productivity of many annual vegetables.

Practical tips for preserving mycelium include maintaining optimal growing conditions post-harvest. Keep the substrate at a consistent temperature (typically 60-75°F) and humidity (50-70%). Avoid exposing the mycelium to direct sunlight or drafts, which can stress the network. If using a grow bag or container, ensure it has proper ventilation to prevent CO2 buildup. Regularly inspect the substrate for signs of contamination, such as mold or unusual discoloration, and address issues promptly. By treating mycelium as a living, breathing organism, you can maximize its productivity and ensure a steady supply of mushrooms.

In conclusion, harvesting mushrooms without damaging mycelium requires a combination of gentle techniques, environmental awareness, and patience. By understanding the regenerative nature of fungi and adopting careful practices, cultivators can enjoy multiple flushes from a single batch of mycelium. This approach not only increases yield but also aligns with sustainable farming principles, making mushroom cultivation an eco-friendly and rewarding endeavor.

Household Mushrooms: Hidden Health Risks and How to Stay Safe

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mycelium Storage Methods

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, is a resilient organism capable of surviving in various conditions, but proper storage is crucial for maintaining its viability for future mushroom cultivation. One of the most effective methods is refrigeration, which slows down the metabolic activity of the mycelium, extending its shelf life. Store mycelium-inoculated substrates like grain or agar plates in airtight containers at temperatures between 2°C and 4°C (36°F to 39°F). This method can preserve mycelium for 6 to 12 months, depending on the species. For longer-term storage, ensure the containers are labeled with the date and strain to track viability over time.

For those seeking even more extended preservation, cryogenic storage offers a solution. This involves freezing mycelium in liquid nitrogen at -196°C (-320°F), effectively halting all biological activity. While this method can preserve mycelium indefinitely, it requires specialized equipment and is typically used by research institutions or large-scale cultivators. A more accessible alternative is home freezing, where mycelium-colonized grain is stored in a standard freezer at -18°C (0°F). Though not as long-lasting as cryogenic storage, this method can keep mycelium viable for 1 to 2 years if properly sealed in vacuum bags or airtight containers.

Another innovative approach is desiccation, which involves drying mycelium to remove moisture and inhibit growth. This method is particularly useful for transporting mycelium over long distances or storing it in environments without refrigeration. To desiccate mycelium, spread it thinly on a surface and allow it to air-dry completely, or use a food dehydrator set at low temperatures. Once dried, store the mycelium in a cool, dark place in airtight containers with silica gel packets to absorb any residual moisture. While desiccation can reduce viability over time, it remains a practical option for short-term storage or emergency preservation.

Lastly, agar storage is a preferred method for maintaining pure mycelium cultures. By transferring mycelium to agar plates and storing them in a refrigerator, cultivators can preserve uncontaminated cultures for up to a year. For added longevity, slant cultures—where agar is poured into test tubes at an angle—reduce the surface area exposed to air, minimizing contamination risk. These slants can be stored in a refrigerator and periodically transferred to fresh agar to maintain viability. This method is ideal for hobbyists and professionals alike, ensuring a reliable source of mycelium for future inoculations.

Each storage method has its advantages and limitations, and the choice depends on the cultivator’s resources, goals, and scale of operation. Refrigeration and freezing are accessible and effective for most home growers, while desiccation offers portability and simplicity. Agar storage, on the other hand, is essential for maintaining pure cultures over time. By understanding these techniques, cultivators can ensure a continuous supply of viable mycelium, enabling sustained mushroom production.

Cooked Mushrooms and Diverticulitis: Safe or Risky for Your Diet?

You may want to see also

Signs of Mycelium Exhaustion

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, is the backbone of mushroom cultivation. However, like any living organism, it has limits. Recognizing the signs of mycelium exhaustion is crucial for maintaining a productive mushroom farm. One of the earliest indicators is a significant slowdown in mushroom production despite optimal growing conditions. If your substrate, temperature, and humidity are ideal but yields continue to decline, the mycelium may be nearing the end of its productive lifecycle. This occurs because the mycelium depletes available nutrients and energy reserves, leading to reduced fruiting.

Another telltale sign is the appearance of smaller, underdeveloped mushrooms or pins that fail to mature. Healthy mycelium typically produces robust, fully formed fruiting bodies. When the mycelium is exhausted, it lacks the vigor to support proper mushroom development. Additionally, the color and texture of the mycelium itself can provide clues. Exhausted mycelium often appears darker, less vibrant, and may develop a dry, brittle texture compared to its usual white, fluffy appearance. These physical changes signal that the mycelium is struggling to sustain itself.

For those using grain spawn or supplemented sawdust blocks, monitor the substrate for signs of contamination. Exhausted mycelium is more susceptible to competing molds and bacteria, which can quickly take over the growing medium. If you notice unusual colors (like green or black spots) or foul odors, it’s a strong indication that the mycelium is no longer dominant and the substrate is compromised. At this stage, salvaging the batch becomes difficult, and starting anew is often the best course of action.

To mitigate mycelium exhaustion, consider rotating substrates or replenishing nutrients. For example, adding a small amount of fresh grain to an existing block can sometimes revive flagging mycelium. However, this is a temporary solution, as the mycelium’s lifespan is inherently finite. Most mycelium cultures remain productive for 3–6 months, depending on the species and growing conditions. Beyond this, plan to propagate new mycelium from healthy tissue or spores to ensure consistent yields.

In summary, mycelium exhaustion manifests through reduced yields, stunted mushroom growth, physical changes in the mycelium, and increased susceptibility to contamination. While short-term interventions can sometimes extend productivity, understanding these signs allows cultivators to prepare for inevitable renewal. By recognizing exhaustion early, growers can maintain a steady supply of mushrooms without prolonged downtime.

Can You Eat Cold Mushroom Risotto? A Tasty Twist Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, mycelium has a finite lifespan and will eventually exhaust its energy reserves or become less productive over time.

It depends on the species and conditions, but typically 2-5 flushes (harvests) are possible before the mycelium weakens.

Yes, if the mycelium is healthy and properly maintained, it can be reused for additional flushes or transferred to new substrate.

Yes, mycelium benefits from a resting period (usually a few days to a week) between flushes to recover and produce more mushrooms.

Yes, mycelium can be stored in a dormant state (e.g., in a refrigerator or dried) for several months to a year, depending on the species and storage conditions.