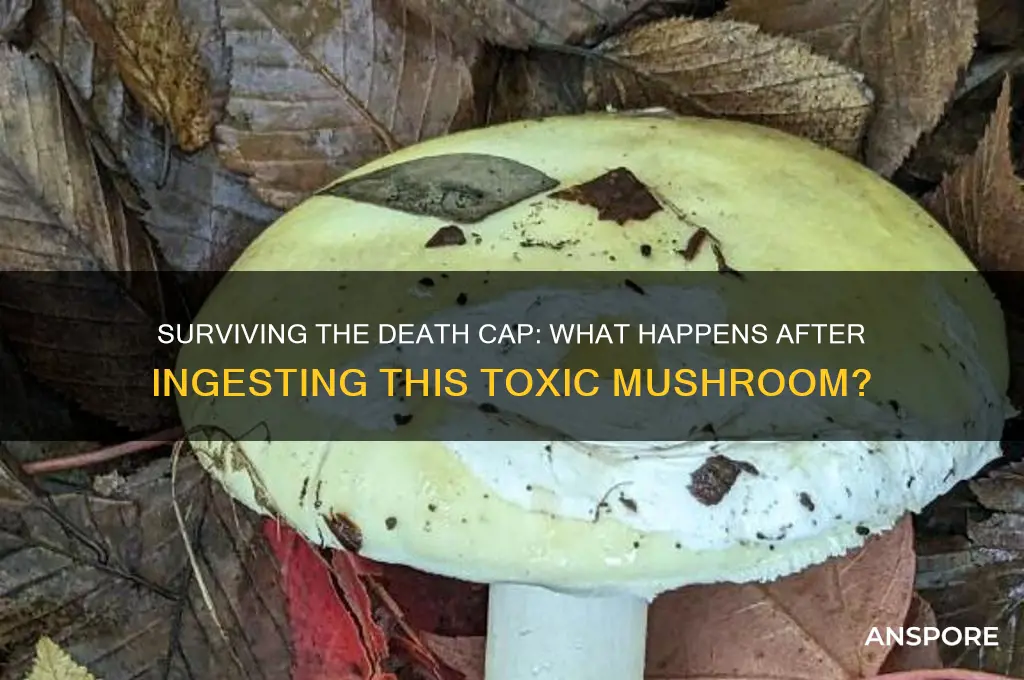

The death cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings globally. Its toxins, primarily amatoxins, cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure if left untreated. Despite its deadly reputation, survival is possible if medical intervention is sought immediately after ingestion. Early symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, may appear 6–24 hours after consumption, followed by a seemingly recovery period before critical organ damage manifests. Prompt treatment, including gastric decontamination, supportive care, and medications like silibinin or liver transplantation in severe cases, significantly improves survival rates. However, the outcome depends on the amount ingested, the time elapsed before treatment, and the individual’s overall health, making immediate medical attention crucial.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Name | Death Cap Mushroom |

| Toxicity | Extremely toxic, contains amatoxins (alpha-amanitin, beta-amanitin) |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Initial: gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain); Later: liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, coma |

| Onset of Symptoms | 6-24 hours after ingestion (delayed onset is common) |

| Fatality Rate | 10-50% without treatment; lower with prompt medical intervention |

| Treatment | Gastric decontamination, activated charcoal, supportive care, liver transplant in severe cases |

| Survival Possibility | Yes, with immediate medical treatment and early diagnosis |

| Key to Survival | Early recognition of symptoms and medical intervention |

| Prevention | Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless identified by an expert |

| Geographic Distribution | Widespread, found in Europe, North America, Australia, and other regions |

| Season | Typically appears in late summer and autumn |

| Misidentification Risk | High, often mistaken for edible mushrooms like straw mushrooms or caesar’s mushroom |

| Long-Term Effects | Possible chronic liver damage in survivors |

| Antidote | None specific, but silibinin (milk thistle extract) may help protect the liver |

Explore related products

$8.99 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, liver failure, and potential organ damage

- Toxic Compounds: Amatoxins destroy liver and kidney cells, leading to severe health complications

- Treatment Options: Immediate medical care, activated charcoal, liver transplant, and supportive therapy

- Survival Rates: Depends on timing of treatment; early intervention increases chances of survival

- Prevention Tips: Proper mushroom identification, avoid wild foraging without expertise, and seek professional guidance

Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, liver failure, and potential organ damage

The first signs of death cap mushroom poisoning are deceptively mundane: nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These symptoms typically appear 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, lulling victims into a false sense of security. They might mistake the illness for a stomach bug or food poisoning. However, this initial phase is a critical warning sign. The amatoxins in the death cap are already at work, silently damaging liver cells.

Vomiting and diarrhea, while uncomfortable, serve a purpose: they’re the body’s attempt to expel the toxin. But this also leads to rapid fluid loss, causing dehydration. For adults, losing just 3-4% of body fluids can impair cognitive function; in children, the threshold is even lower. Rehydration is crucial, but it’s a temporary fix. The real danger lies in what’s happening internally. Amatoxins infiltrate liver cells, disrupting protein synthesis and causing irreversible damage.

Liver failure is the hallmark of death cap poisoning. Within 24 to 48 hours, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) may appear as the liver struggles to filter bilirubin. Blood tests will show skyrocketing levels of liver enzymes (ALT and AST), often exceeding 1,000 U/L—a stark contrast to the normal range of 7-56 U/L. Without intervention, the liver’s inability to detoxify the body leads to a cascade of organ failures: kidneys shut down, the brain swells, and coagulation disorders cause uncontrollable bleeding.

Survival hinges on early treatment. Activated charcoal, administered within hours of ingestion, can bind remaining toxins in the gut. Intravenous fluids combat dehydration, and medications like N-acetylcysteine may mitigate liver damage. In severe cases, a liver transplant is the only option. However, time is the enemy. Delayed treatment reduces survival odds from 90% to less than 50%.

Prevention is paramount. Death caps resemble edible mushrooms like the straw mushroom, often fooling foragers. Always cross-reference findings with multiple guides, and when in doubt, consult an expert. Remember: no meal is worth risking organ failure. If ingestion is suspected, seek medical help immediately—even if symptoms seem mild. The death cap’s toxins are silent but relentless, and every minute counts.

Can Horses Safely Eat Wild Mushrooms? Risks and Precautions

You may want to see also

Toxic Compounds: Amatoxins destroy liver and kidney cells, leading to severe health complications

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is infamous for its deadly toxicity, primarily due to a group of compounds called amatoxins. These toxins are relentless in their attack on the body’s vital organs, specifically targeting liver and kidney cells. Within 6 to 12 hours of ingestion, symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea appear, often misleading victims into thinking it’s a harmless case of food poisoning. However, this is just the beginning. Amatoxins infiltrate cells, inhibiting RNA polymerase II, a critical enzyme for protein synthesis. Without this enzyme, cells cannot repair themselves, leading to rapid tissue breakdown. The liver, responsible for detoxifying the body, is overwhelmed, and kidney function deteriorates as toxins accumulate. This dual assault can result in liver and kidney failure within 48 to 72 hours, making immediate medical intervention crucial.

Understanding the dosage of amatoxins required to cause harm is essential for prevention and treatment. As little as half a death cap mushroom contains enough amatoxins to kill an adult. Children are even more vulnerable, with a single bite potentially proving fatal. Amatoxins are heat-stable, meaning cooking or drying the mushroom does not neutralize their toxicity. This makes accidental ingestion particularly dangerous, as victims may mistakenly believe preparation methods can render the mushroom safe. Early symptoms can be deceptive, often subsiding temporarily before severe organ damage becomes apparent. This "honeymoon phase" can delay treatment, increasing the risk of irreversible harm.

Treatment for amatoxin poisoning is a race against time. Activated charcoal may be administered to reduce toxin absorption if given within hours of ingestion. Intravenous fluids and medications like silibinin, a milk thistle extract, can help protect liver cells. In severe cases, a liver transplant may be the only option for survival. However, the window for effective treatment is narrow, emphasizing the importance of rapid identification and medical care. Public awareness campaigns and accurate mushroom identification guides are critical tools in preventing accidental poisoning, especially in regions where death caps thrive, such as North America, Europe, and Australia.

Comparing amatoxin poisoning to other toxic exposures highlights its unique dangers. Unlike many toxins, amatoxins are not immediately lethal, allowing victims to feel relatively well for hours before organ failure sets in. This delayed onset complicates diagnosis, as symptoms mimic common gastrointestinal illnesses. In contrast, toxins like cyanide or arsenic cause rapid, unmistakable symptoms, prompting immediate medical attention. Amatoxins’ insidious nature requires a high index of suspicion, particularly during mushroom foraging season. Educating the public about the death cap’s distinctive features—such as its greenish cap, white gills, and bulbous base—can reduce the risk of accidental ingestion.

For those who survive amatoxin poisoning, the road to recovery is long and challenging. Even with successful treatment, residual liver and kidney damage can persist, requiring ongoing monitoring and care. Survivors often report fatigue, weakness, and digestive issues for months or even years afterward. This underscores the importance of prevention over cure. Avoiding wild mushroom foraging without expert guidance, teaching children not to consume unknown fungi, and promptly seeking medical attention for suspected poisoning are simple yet life-saving measures. The death cap’s toxicity serves as a stark reminder of nature’s dual capacity for beauty and danger, demanding respect and caution.

Mushrooms and Erectile Dysfunction: Unraveling the Surprising Connection

You may want to see also

Treatment Options: Immediate medical care, activated charcoal, liver transplant, and supportive therapy

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings. Survival after ingestion depends critically on the speed and effectiveness of treatment. Immediate medical care is non-negotiable; delay can be fatal. Upon suspicion of ingestion, seek emergency services without waiting for symptoms, as the toxin, amatoxin, can cause irreversible damage within hours. Hospitals will often administer activated charcoal to bind the toxin in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing absorption. However, this is most effective if given within the first hour, underscoring the urgency of swift action.

Activated charcoal is a cornerstone of initial treatment but is not a standalone solution. Administered orally in doses of 1–2 g/kg for adults and adjusted for children, it works by adsorbing toxins in the gut. Despite its utility, it does not counteract toxins already absorbed into the bloodstream, which is why it must be paired with other interventions. Medical professionals may also use gastric lavage (stomach pumping) or administer laxatives to expedite toxin elimination, though these procedures are more invasive and reserved for severe cases.

When amatoxins reach the liver, they cause rapid and severe damage, often leading to liver failure within 48–72 hours. In such cases, a liver transplant may be the only life-saving option. This drastic measure is considered for patients with acute liver failure who do not respond to other treatments. However, it is a complex and resource-intensive procedure, requiring a compatible donor and immediate surgical intervention. Survival rates post-transplant are relatively high, but the window for success is narrow, emphasizing the need for early detection and treatment.

Supportive therapy plays a critical role in managing symptoms and stabilizing the patient while the body attempts to recover. This includes intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration, electrolyte monitoring to address imbalances, and medications to manage complications like coagulopathy or kidney dysfunction. In severe cases, patients may require dialysis if kidney function is compromised. Pain management and nutritional support are also essential, as the body’s metabolic demands increase during the toxic crisis. While supportive therapy alone cannot neutralize amatoxins, it buys time and improves the chances of survival, particularly when combined with other treatments.

In summary, surviving death cap mushroom poisoning hinges on a multi-faceted treatment approach. Immediate medical care, activated charcoal, liver transplantation, and supportive therapy each play distinct but interconnected roles. Speed is paramount, as delays reduce the effectiveness of interventions. Public awareness of these treatment options and the importance of prompt action can make the difference between life and death. Always remember: if ingestion is suspected, act immediately—time is not on your side.

Ranch as Cream of Mushroom Substitute in Green Bean Casserole?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Rates: Depends on timing of treatment; early intervention increases chances of survival

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings. Its toxins, primarily amatoxins, cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure. Yet, survival is not impossible—it hinges critically on the timing of treatment. The window for effective intervention is narrow, typically within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, making swift action paramount.

Consider the steps to maximize survival chances. First, immediate medical attention is non-negotiable. If ingestion is suspected, call emergency services or a poison control center without delay. While waiting for help, do not induce vomiting unless instructed by a professional, as it can exacerbate toxin absorption. Activated charcoal, administered by medical personnel, may help reduce toxin uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. For those who reach a hospital within the critical window, treatments like intravenous fluids, silibinin (a milk thistle extract), and, in severe cases, liver transplantation, can be life-saving.

The survival rate varies dramatically based on treatment timing. Studies show that individuals treated within 6 hours of ingestion have a survival rate exceeding 90%, while those treated after 24 hours face significantly worse odds, often below 50%. Age and overall health also play a role; children and the elderly are more vulnerable due to less resilient organ function. For instance, a 2014 case study highlighted a 57-year-old patient who survived after consuming a death cap, thanks to early intervention and a liver transplant within 72 hours.

Practical tips for prevention are equally vital. Misidentification is the primary cause of death cap poisoning, as it resembles edible mushrooms like the paddy straw mushroom. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable guides, and when in doubt, discard the mushroom. Cooking or drying does not neutralize amatoxins, so even small quantities can be lethal. For foragers, carrying a mushroom identification app or guide and avoiding consumption of wild mushrooms altogether are prudent measures.

In conclusion, surviving death cap poisoning is a race against time. Early recognition, prompt medical intervention, and access to specialized treatments are the cornerstones of survival. While the toxin’s potency is formidable, awareness and swift action can tip the scales in favor of life.

Portobello Mushrooms: Optimal Fridge Storage Time and Freshness Tips

You may want to see also

Prevention Tips: Proper mushroom identification, avoid wild foraging without expertise, and seek professional guidance

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Its innocuous appearance often leads to misidentification, making proper knowledge and caution essential. Prevention begins with understanding the risks and adopting practices that minimize exposure to this deadly fungus.

Master the Art of Mushroom Identification

Accurate identification is the cornerstone of safe foraging. Death caps resemble edible species like the straw mushroom or young puffballs, but subtle differences exist. Key features to note include the death cap’s greenish-yellow cap, white gills, and volva (a cup-like structure at the base). Invest in a reputable field guide, such as *Mushrooms Demystified* by David Arora, and cross-reference findings with multiple sources. Use a magnifying glass to examine spore prints—death caps produce white spores, while some edible look-alikes produce different colors. Practice identification with experts before trusting your skills alone.

Avoid Wild Foraging Without Expertise

Foraging without proper knowledge is akin to playing Russian roulette with nature. Even experienced foragers occasionally make mistakes, but beginners are at highest risk. If you’re unsure, assume all wild mushrooms are toxic. Avoid collecting mushrooms near urban areas, where death caps thrive in gardens and parks due to their symbiotic relationship with hardwood trees. Instead, focus on cultivating edible varieties at home or purchasing from certified vendors. Remember, no meal is worth risking your life.

Seek Professional Guidance

When in doubt, consult a mycologist or join a local mycological society. Many regions offer workshops or guided foraging tours led by experts who can teach you to identify death caps and other toxic species. Apps and online forums are helpful but not infallible—always verify information with a professional. If you suspect ingestion of a death cap, seek immediate medical attention. Early treatment, including activated charcoal and supportive care, can improve survival rates, but time is critical.

Practical Tips for Safe Foraging

Carry a knife and basket when foraging to avoid damaging mushrooms or mixing species. Cut specimens at the base to examine the stem and volva intact. Avoid collecting in areas treated with pesticides or near roadsides. Teach children to never touch or taste wild mushrooms, and supervise pets in areas where death caps grow. By combining vigilance, education, and respect for nature, you can enjoy the wonders of fungi without endangering yourself or others.

Creative HMR Mushroom Risotto Recipes: Easy, Delicious Meal Ideas

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, survival is possible if medical treatment is sought immediately. However, the death cap (Amanita phalloides) is highly toxic, and delays in treatment significantly increase the risk of liver failure and death.

Symptoms typically appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This delay can make diagnosis challenging.

Seek emergency medical attention immediately. Call poison control or go to the nearest hospital. Do not wait for symptoms to appear, as early treatment improves survival chances.

No, there are no effective home remedies. Professional medical treatment, including activated charcoal, intravenous fluids, and potentially liver transplantation, is essential for survival.

It is not always fatal, but it is extremely dangerous. With prompt and proper medical care, survival rates can be as high as 70–90%. However, without treatment, the mortality rate is around 50–90%.