Creating mushroom spawn from mushrooms is a fascinating process that allows cultivators to propagate specific mushroom strains for cultivation. While it is possible to make mushroom spawn from mature mushrooms, it requires careful attention to sterility and technique. The process typically involves isolating the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—from the mushroom’s stem or cap, then transferring it to a nutrient-rich substrate like grain or sawdust. This substrate becomes colonized by the mycelium, producing spawn that can be used to grow more mushrooms. However, success depends on preventing contamination from competing microorganisms, as mushrooms are prone to mold and bacteria. With proper sterilization and knowledge, this method offers a sustainable way to expand mushroom cultivation, though it is often more challenging than using commercially produced spawn.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Possibility | Yes, it is possible to make mushroom spawn from mushrooms under certain conditions. |

| Required Mushroom Type | Healthy, disease-free mushrooms with well-developed mycelium (e.g., oyster, shiitake, lion's mane). |

| Method | Tissue culture or fragmentation of mycelium from the mushroom stem or gills. |

| Sterility | High sterility is required to prevent contamination by bacteria, molds, or other fungi. |

| Substrate | Sterilized grain (e.g., rye, wheat, millet) or sawdust is commonly used as a substrate for mycelium growth. |

| Success Rate | Varies; higher success with sterile techniques and suitable mushroom species. |

| Time Frame | 2-6 weeks for mycelium to colonize the substrate, depending on species and conditions. |

| Equipment Needed | Sterile workspace, pressure cooker, scalpel, petri dishes, agar, and jars/bags for substrate. |

| Common Challenges | Contamination, improper sterilization, and unsuitable mushroom species. |

| Alternative Methods | Purchasing pre-made spawn or using wild mushroom patches (less reliable). |

| Cost | Low to moderate, depending on equipment and materials. |

| Scalability | Suitable for small-scale cultivation; larger operations often use commercial spawn. |

| Legal Considerations | Check local regulations for cultivating specific mushroom species. |

| Environmental Factors | Temperature, humidity, and light conditions must be controlled for optimal mycelium growth. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sterilization Techniques: Methods to ensure a sterile environment for mushroom spawn production

- Substrate Preparation: Choosing and preparing materials for mushroom spawn growth

- Spawn Types: Differences between grain, sawdust, and liquid mushroom spawn

- Inoculation Process: Steps to introduce mushroom mycelium into the substrate

- Storage & Viability: How to store mushroom spawn for long-term use

Sterilization Techniques: Methods to ensure a sterile environment for mushroom spawn production

Creating mushroom spawn from existing mushrooms is a feasible and rewarding process, but success hinges on maintaining a sterile environment. Contamination by competing microorganisms can derail your efforts, making sterilization techniques the cornerstone of spawn production. Here’s how to ensure your workspace and materials remain pristine.

Pressure Cooking: The Gold Standard

The most reliable method for sterilizing grain or substrate is using a pressure cooker. Aim for 15 psi (pounds per square inch) at 121°C (250°F) for 60–90 minutes. This kills spores, bacteria, and fungi that could compete with your mushroom mycelium. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for your specific cooker, and ensure the lid is sealed tightly to maintain pressure. For larger batches, consider a commercial-grade autoclave, which operates on similar principles but at a larger scale.

Chemical Sterilization: A Precise Alternative

For tools, surfaces, or small items, chemical sterilants like hydrogen peroxide (3–6% solution) or isopropyl alcohol (70–90%) are effective. Wipe down work surfaces and tools thoroughly, allowing them to air-dry in a laminar flow hood or clean environment. For liquid cultures, a 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) can sterilize containers, but rinse thoroughly afterward to avoid residue. Always handle chemicals with gloves and proper ventilation.

Flaming: Quick and Targeted

For small items like inoculation loops, needles, or jar lids, direct flame sterilization is efficient. Pass the item through a bunsen burner’s flame until it glows red, ensuring all surfaces are exposed. This method is ideal for tools used during the transfer of mycelium to substrate. Be cautious to avoid overheating or melting materials, and always work in a well-ventilated area.

Comparing Methods: Pros and Cons

Pressure cooking is foolproof but time-consuming, while chemical sterilization is quicker but less effective against spores. Flaming is instant but limited to small items. The choice depends on your setup and the materials being sterilized. For home cultivators, a combination of pressure cooking for substrate and chemical/flame sterilization for tools often yields the best results.

Practical Tips for Success

Work in a clean, designated area, and wear a mask and gloves to minimize contamination. Allow sterilized items to cool in a still air box or under a laminar flow hood before use. Always inspect your substrate post-sterilization for signs of contamination, such as discoloration or off-odors. Consistency in technique and attention to detail will dramatically increase your chances of producing healthy, viable mushroom spawn.

Are Canned Mushrooms Safe? Risks of Overconsumption Explained

You may want to see also

Substrate Preparation: Choosing and preparing materials for mushroom spawn growth

Mushroom spawn production begins with the substrate, the material that nourishes mycelium growth. Selecting the right substrate is critical, as different mushroom species thrive on specific organic matter. Common substrates include straw, wood chips, sawdust, and grain. For instance, oyster mushrooms excel on straw, while shiitakes prefer hardwood sawdust. The substrate must be rich in cellulose or lignin, providing the energy mycelium needs to colonize and produce spawn.

Preparation of the substrate involves sterilization or pasteurization to eliminate competing microorganisms. Sterilization, typically done in an autoclave at 121°C (250°F) for 1-2 hours, is essential for grain-based substrates like rye or wheat berries. Pasteurization, a milder process involving soaking straw in hot water (70-80°C or 158-176°F) for 1-2 hours, suffices for straw or wood-based substrates. Both methods ensure a clean environment for mycelium to dominate, reducing the risk of contamination.

Hydration is another key step in substrate preparation. The material must be moist but not waterlogged, as excess moisture fosters bacterial growth. Aim for a moisture content of 60-70% by weight. To test, squeeze a handful of substrate—it should release a few drops of water. Adjust by adding water or letting it drain as needed. Proper hydration ensures mycelium can spread efficiently without drowning.

Once prepared, the substrate is cooled to room temperature before inoculation with mushroom mycelium. This prevents heat damage to the delicate mycelial culture. For grain substrates, allow the sterilized grains to cool in a clean environment, such as a still air box, to avoid airborne contaminants. Straw or wood substrates should be spread out in a thin layer to cool quickly and evenly.

Finally, store prepared substrates in a sterile container or bag until ready for use. Label with the substrate type, preparation date, and intended mushroom species for organization. Proper substrate preparation is the foundation of successful spawn production, ensuring healthy mycelium growth and robust mushroom yields. Master this step, and you’ll unlock the potential to cultivate spawn from mushrooms effectively.

Unlocking Growth: Plants and Vegetables Thriving in Mushroom Compost

You may want to see also

Spawn Types: Differences between grain, sawdust, and liquid mushroom spawn

Mushroom spawn serves as the foundation for successful cultivation, but not all spawn types are created equal. Grain, sawdust, and liquid spawn each offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different cultivation methods and mushroom species. Understanding these differences is crucial for optimizing yield, cost, and ease of use.

Grain spawn, typically made from rye, wheat, or millet, is a popular choice for beginners due to its simplicity and versatility. The process involves sterilizing the grains, inoculating them with mushroom mycelium, and allowing the mycelium to colonize the substrate. Grain spawn is ideal for small-scale cultivation and species like oyster mushrooms, which thrive on nutrient-rich substrates. However, its high moisture content can lead to contamination if not managed properly. To mitigate this, ensure proper sterilization and maintain a clean environment during inoculation.

Sawdust spawn, on the other hand, is favored for its longevity and suitability for wood-loving mushrooms like shiitake and reishi. Made by mixing sawdust with nutrients like bran or gypsum, it provides a low-moisture environment that resists contamination. Sawdust spawn is often used in outdoor log or tote-based cultivation, where it can remain viable for months. While more complex to prepare than grain spawn, its durability makes it a cost-effective option for long-term projects. For best results, use hardwood sawdust and supplement with nitrogen-rich additives to support mycelial growth.

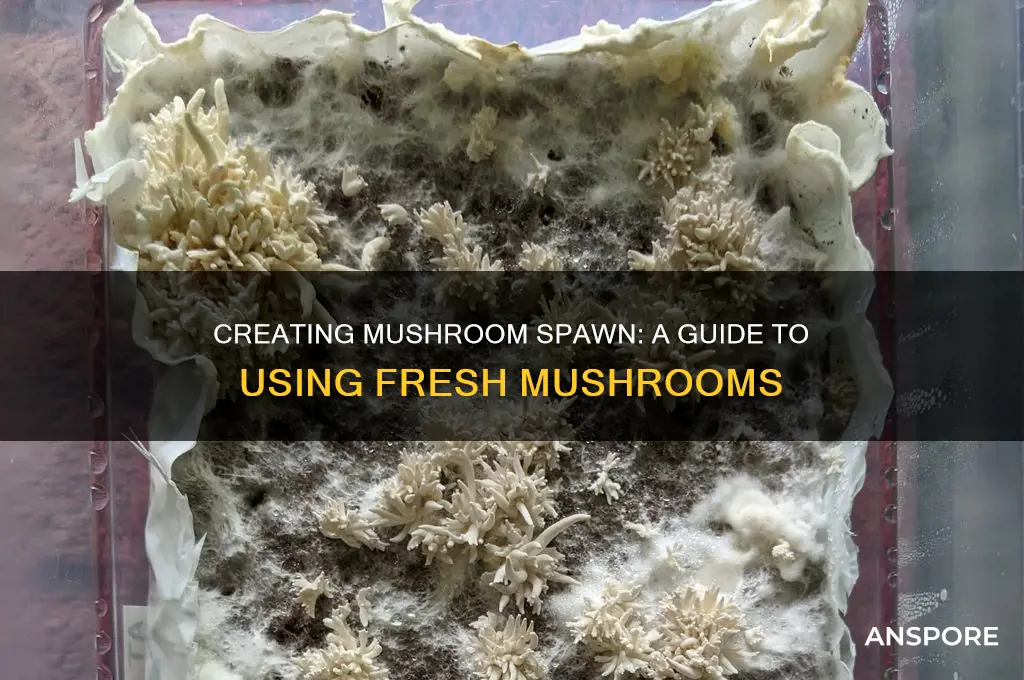

Liquid spawn represents a modern innovation, offering a highly efficient and scalable solution for commercial growers. Created by suspending mycelium in a nutrient-rich liquid medium, it can be easily distributed across large substrates using injection or spraying techniques. This method is particularly effective for fast-colonizing species like lion’s mane and is ideal for automated or high-volume production systems. However, liquid spawn requires precise sterilization and handling to prevent contamination. Its higher initial cost is offset by its ability to inoculate vast quantities of substrate quickly, making it a game-changer for industrial-scale cultivation.

Choosing the right spawn type depends on your cultivation goals, mushroom species, and available resources. Grain spawn is beginner-friendly and versatile, sawdust spawn excels in durability and wood-based cultivation, and liquid spawn offers unmatched efficiency for large-scale operations. By tailoring your spawn selection to your specific needs, you can maximize productivity and ensure a successful mushroom harvest.

Mixing Psychedelics: Risks of Taking Acid After Mushrooms Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Inoculation Process: Steps to introduce mushroom mycelium into the substrate

The inoculation process is a delicate dance, a precise introduction of mushroom mycelium into a substrate, setting the stage for a thriving fungal colony. This critical step demands attention to detail, as it directly influences the success of your mushroom cultivation. Imagine a tiny army of mycelial threads, ready to conquer and colonize, but their journey begins with a careful and calculated invasion.

Preparation is Key: Before the mycelium meets the substrate, ensure both are in optimal condition. The substrate, often a blend of organic materials like straw, wood chips, or grain, must be pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competitors and create a welcoming environment. This process varies; for instance, straw can be soaked in hot water (around 60-70°C) for an hour, while grain substrates often require pressure cooking at 121°C for 30-60 minutes. Simultaneously, the mycelium, typically grown on a grain spawn, should be healthy and vigorous, with a robust network of white, thread-like structures.

Inoculation Techniques: There are several methods to introduce the mycelium, each with its nuances. One common approach is the 'spawn to substrate' technique, where the grain spawn is mixed directly into the prepared substrate. For every 10 pounds of substrate, approximately 1-2 pounds of grain spawn is recommended, ensuring an even distribution. Another method, 'spawn bags,' involves placing the substrate into a bag, then introducing the mycelium through a small opening, allowing it to colonize the bag's contents. This technique is often used for more delicate substrates.

Caution and Precision: Inoculation requires a sterile environment to prevent contamination. Work in a clean space, and consider using a still air box or laminar flow hood for advanced setups. Sterilize all tools, and ensure your hands are clean and sanitized. The mycelium is sensitive; avoid exposing it to direct sunlight or extreme temperatures. After inoculation, maintain a stable environment, typically around 22-25°C, and monitor for signs of growth, which should appear within 7-14 days.

The Art of Timing: Knowing when to inoculate is crucial. For outdoor beds, aim for a time when temperatures are mild, avoiding extreme heat or cold. Indoor growers can control this more precisely. The substrate should be cool enough to handle but not cold, ideally around 20-25°C. Too warm, and you risk cooking the mycelium; too cold, and colonization slows. This process is a balance of science and art, where precision and patience are rewarded with a flourishing mycelial network, the foundation of a successful mushroom harvest.

In the world of mushroom cultivation, the inoculation process is a pivotal moment, a carefully orchestrated event that determines the fate of your fungal crop. It's a blend of scientific precision and natural wonder, where the right conditions and techniques unlock the potential for abundant mushroom growth.

Can You Eat Stinkhorn Mushrooms? Risks, Benefits, and Safe Identification

You may want to see also

Storage & Viability: How to store mushroom spawn for long-term use

Storing mushroom spawn for long-term use requires careful consideration of environmental factors to maintain viability. Temperature is critical: most spawn thrives at 2–4°C (36–39°F), mirroring refrigerator conditions. At this range, metabolic activity slows, preserving energy reserves without inducing dormancy. Avoid freezing, as ice crystals can rupture cell walls, rendering the spawn unusable. Conversely, temperatures above 10°C (50°F) accelerate aging, reducing shelf life from months to weeks. Humidity control is equally vital; store spawn in sealed containers with 70–80% relative humidity to prevent desiccation, which can halt mycelial growth.

The choice of storage medium significantly impacts longevity. Grain spawn, such as rye or millet, is popular due to its stability but requires sterilization before use to prevent contamination. Sawdust spawn, while lighter, is more prone to drying and benefits from vacuum-sealed packaging. Liquid cultures, stored in sterile syringes, offer convenience but degrade faster, typically lasting 6–12 months. For extended storage, consider agar cultures, which can remain viable for 1–2 years when refrigerated in sealed Petri dishes. Always label containers with the date and strain to track viability.

To maximize viability, adopt a multi-layered storage approach. Begin by inoculating a master culture on agar, which serves as a long-term backup. Transfer mycelium from this culture to grain spawn for intermediate storage, and use this spawn to produce sawdust or liquid cultures for immediate use. This tiered system ensures genetic stability and reduces the risk of contamination. Periodically refresh cultures every 6–12 months by transferring mycelium to fresh agar or grain to rejuvenate weakened spawn.

Practical tips can further enhance storage success. For grain spawn, use wide-mouth mason jars with filtered lids to allow gas exchange while blocking contaminants. Liquid cultures benefit from storage in the darkest part of the refrigerator, as light can degrade mycelium. If refrigeration is unavailable, consider desiccating mycelium on sterile paper for room-temperature storage, though this method reduces viability to 6–12 months. Regularly inspect stored spawn for signs of mold or discoloration, discarding any compromised material immediately.

Long-term storage is a balance of science and vigilance. While mushroom spawn can remain viable for years under ideal conditions, neglect or improper handling can render it inert within months. By controlling temperature, humidity, and medium, and adopting a systematic approach to preservation, cultivators can safeguard their spawn for future use. Whether for commercial production or hobbyist experimentation, mastering storage techniques ensures a reliable supply of healthy mycelium, reducing waste and increasing success rates in fruiting endeavors.

Can You Eat Black Trumpet Mushrooms? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all mushrooms are suitable for making spawn. Only certain species, such as oyster mushrooms, shiitake, and lion's mane, are commonly used because they are easy to cultivate and have reliable growth patterns.

The process involves sterilizing a substrate (like grain or sawdust), inoculating it with mushroom mycelium (often from a tissue culture or existing spawn), and allowing the mycelium to colonize the substrate. This colonized substrate becomes the spawn.

Yes, you’ll need basic equipment like a pressure cooker for sterilization, sterile containers, a laminar flow hood or still air box to maintain sterility, and a clean workspace to prevent contamination.

The time varies depending on the mushroom species and substrate used, but it typically takes 2–4 weeks for the mycelium to fully colonize the substrate and create viable spawn.

It’s not recommended, as store-bought mushrooms are often treated with chemicals or grown in conditions that may not produce healthy mycelium. It’s better to use tissue cultures or spawn from a reputable supplier for reliable results.