The Death Cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings globally. Its innocuous appearance often leads to accidental ingestion, as it resembles edible species like the button mushroom or the paddy straw mushroom. Despite its deadly reputation, survival is possible if prompt medical intervention is sought. Treatment typically involves gastric decontamination, supportive care, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation. However, the toxin, alpha-amanitin, can cause irreversible liver and kidney damage within 24 to 48 hours of consumption, making early identification and treatment critical. Understanding the risks and symptoms associated with Death Cap poisoning is essential for anyone foraging wild mushrooms or living in areas where this fungus thrives.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Name | Death Cap Mushroom |

| Toxicity Level | Extremely toxic (lethal in many cases) |

| Toxins Present | Amatoxins (e.g., alpha-amanitin, beta-amanitin) |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Initial: Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain); Later: Liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, coma |

| Onset of Symptoms | 6–24 hours after ingestion (delayed symptoms are typical) |

| Survival Rate | ~10–50% depending on prompt medical intervention and severity of poisoning |

| Treatment | Supportive care, activated charcoal, silibinin (milk thistle extract), liver transplant in severe cases |

| Misidentification Risk | Often mistaken for edible mushrooms like straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea) or caesar’s mushroom (Amanita caesarea) |

| Geographic Distribution | Widespread in Europe, North America, Australia, and other temperate regions |

| Season | Late summer to fall (peak season) |

| Prevention | Avoid foraging without expert knowledge; cook all wild mushrooms thoroughly (though cooking does not detoxify death caps) |

| Fatal Dose | As little as half a mushroom for adults; smaller amounts for children |

| Historical Significance | Responsible for numerous fatal poisonings worldwide, including notable cases like the 2016 poisoning in California |

| Edibility | Absolutely not edible; considered one of the most poisonous mushrooms globally |

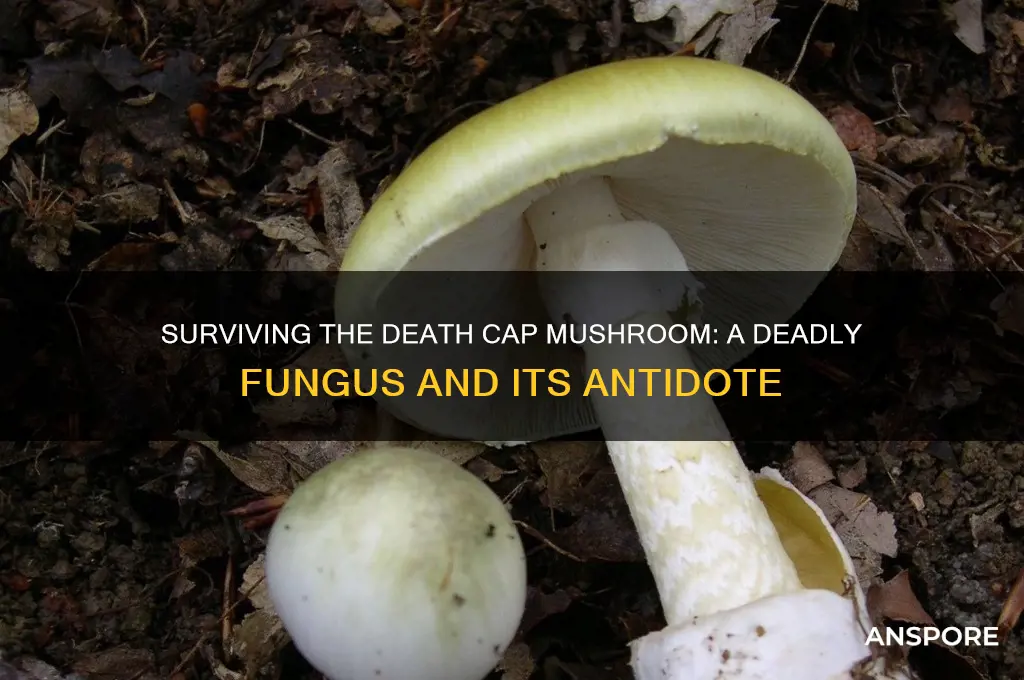

| Physical Description | Greenish-yellow cap, white gills, bulbous base with a cup-like volva, and a ring on the stem |

Explore related products

$19.24 $35

What You'll Learn

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, liver failure, and potential coma within hours

- Toxic Compounds: Amatoxins destroy liver and kidney cells, leading to organ failure

- Treatment Options: Activated charcoal, penicillin, and liver transplants are critical interventions

- Misidentification Risks: Resembles edible mushrooms like straw mushrooms, increasing accidental ingestion

- Survival Rates: Early treatment improves chances, but fatality rates remain high without intervention

Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, liver failure, and potential coma within hours

The death cap mushroom, or *Amanita phalloides*, is notorious for its deadly toxicity, yet its initial symptoms can deceptively mimic common gastrointestinal distress. Within 6 to 24 hours of ingestion, victims often experience nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which might lead them to mistake the poisoning for foodborne illness. This delay in recognizing the true danger is particularly insidious, as it can cause a critical loss of time before seeking medical intervention. These symptoms arise from the mushroom’s amatoxins, which begin to wreak havoc on the body’s cellular processes, particularly targeting the liver.

While nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are the body’s immediate attempts to expel the toxin, they are merely the prelude to far more severe consequences. Amatoxins are not destroyed by digestion and are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream, where they travel to the liver and initiate irreversible damage. Liver failure typically sets in 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, marked by symptoms like jaundice, abdominal pain, and a sudden drop in blood pressure. At this stage, the toxin has already caused extensive cellular death, and without immediate medical intervention, the prognosis becomes dire.

The progression from gastrointestinal distress to liver failure is alarmingly swift, but the most terrifying symptom is the potential for coma, which can occur within hours to days. This is a result of the liver’s inability to filter toxins from the blood, leading to a buildup of harmful substances in the brain. Coma is often a late-stage symptom, signaling multi-organ failure and a critical condition. Survival at this point hinges on emergency liver transplantation or aggressive supportive care, but even then, the mortality rate remains staggeringly high, at around 10-15%.

Practical tips for anyone suspecting death cap ingestion are clear: act immediately. Induce vomiting if ingestion is recent, but do not wait for symptoms to appear. Seek emergency medical care, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification if possible. Time is of the essence, as early administration of activated charcoal, intravenous fluids, and medications like silibinin can mitigate toxin absorption and support liver function. For children, the elderly, or those with pre-existing liver conditions, the risk is exponentially higher, making swift action even more critical.

In comparison to other mushroom poisonings, the death cap’s symptoms are uniquely deceptive and relentless. Unlike the hallucinogenic effects of *Psilocybe* species or the immediate paralysis caused by *Galerina*, the death cap’s toxicity unfolds silently, often lulling victims into a false sense of security. This makes education and awareness paramount. Knowing the symptoms—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, liver failure, and potential coma—can mean the difference between life and death. The death cap’s lethality is not in its immediate effects but in its insidious progression, making it a silent yet deadly threat.

Profitable Mushroom Farming: UK Earnings Potential and Growth Opportunities

You may want to see also

Toxic Compounds: Amatoxins destroy liver and kidney cells, leading to organ failure

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is infamous for its deadly toxicity, primarily due to a group of compounds called amatoxins. These cyclic octapeptides are insidious; they are heat-stable, meaning cooking does not neutralize their toxicity, and they are readily absorbed by the body. Even a small bite—as little as 30 grams of the mushroom, or roughly half a cap—can be fatal for an adult. Children are at even greater risk, as their smaller body mass means a proportionally smaller dose can prove lethal. Understanding the mechanism of amatoxins is crucial for recognizing the severity of ingestion and the urgency of treatment.

Amatoxins exert their lethal effects by targeting and destroying liver and kidney cells, leading to rapid organ failure. Once ingested, these compounds bypass the stomach lining and enter the bloodstream, where they are transported directly to the liver. There, they inhibit RNA polymerase II, a critical enzyme responsible for protein synthesis in cells. Without the ability to produce essential proteins, liver cells begin to die within 6 to 12 hours of ingestion. This process is silent at first, often presenting no symptoms during the initial "latency period." However, as liver function deteriorates, toxins accumulate in the blood, leading to jaundice, abdominal pain, and eventually, acute liver failure. The kidneys, overwhelmed by the toxins and the body’s inflammatory response, soon follow suit, resulting in multi-organ failure.

Immediate medical intervention is the only hope for survival after death cap ingestion. Treatment protocols include gastric decontamination, such as induced vomiting or activated charcoal administration, to reduce toxin absorption. However, these measures are most effective if taken within 1 to 2 hours of ingestion. Beyond this window, the focus shifts to supportive care, including intravenous fluids, electrolyte management, and medications to stabilize blood pressure. In severe cases, a liver transplant may be the only option, but this is often a race against time, as the window for transplantation is narrow, and the procedure is not guaranteed to succeed.

Prevention is the most effective strategy when it comes to amatoxin poisoning. Foraging for wild mushrooms without expert knowledge is extremely risky, as the death cap closely resembles edible species like the straw mushroom or young puffballs. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable guides, and when in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely. Educating children about the dangers of consuming wild plants and fungi is equally vital, as curiosity can lead to accidental ingestion. If exposure is suspected, time is of the essence—seek emergency medical care immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification if possible. Survival hinges on swift action and the body’s ability to withstand the relentless assault of amatoxins.

Chaga Tea and Mushroom Allergies: Safe to Sip or Skip?

You may want to see also

Treatment Options: Activated charcoal, penicillin, and liver transplants are critical interventions

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is notoriously deadly, with a mortality rate of up to 50% if left untreated. Survival hinges on swift, targeted interventions, and among these, activated charcoal, penicillin, and liver transplants stand out as critical tools. Each serves a distinct purpose, addressing the mushroom’s toxic effects at different stages of poisoning. Understanding their roles and limitations is essential for anyone facing this life-threatening emergency.

Activated charcoal is the first line of defense, administered as soon as possible after ingestion. This odorless, tasteless powder binds to the mushroom’s toxins in the gastrointestinal tract, preventing their absorption into the bloodstream. A typical adult dose is 50–100 grams, mixed with water and given orally or via nasogastric tube. For children, the dose is weight-based (1–2 grams per kilogram). Repeated doses may be necessary, especially if vomiting occurs. However, charcoal is most effective within the first hour post-ingestion, underscoring the urgency of immediate action. It’s important to note that charcoal does not reverse damage already done; it merely limits further toxin absorption.

Penicillin, specifically penicillin G, has emerged as a surprising ally in treating death cap poisoning. Studies suggest it competes with the mushroom’s toxin, α-amanitin, for binding sites in the liver, potentially slowing cellular damage. A standard regimen involves high-dose intravenous penicillin G (e.g., 300,000–400,000 units/kg/day for adults) for several days. While not a standalone cure, it buys critical time for the liver to recover or for a transplant to be considered. Caution is advised for patients with penicillin allergies, as alternatives like silibinin (a milk thistle extract) may be explored, though evidence is less robust.

Liver transplants are the last resort, reserved for severe cases where the organ fails irreversibly. α-Amanitin targets liver cells, leading to acute liver failure within 3–5 days post-ingestion. Transplantation offers the only definitive solution, but timing is precarious. Patients must survive long enough for the procedure, often requiring intensive care support, including dialysis and artificial liver devices. Survival rates post-transplant are encouraging, exceeding 80%, but the procedure is costly, invasive, and dependent on donor availability. Early consultation with a transplant center is crucial, even if symptoms seem mild initially.

In practice, these treatments are not mutually exclusive but complementary. Activated charcoal mitigates initial toxin load, penicillin slows progression, and liver transplants address end-stage damage. Success depends on rapid diagnosis, aggressive supportive care, and a multidisciplinary approach. For instance, combining penicillin with N-acetylcysteine (an antioxidant) has shown promise in animal studies, though human data is limited. Patients and caregivers must remain vigilant, as symptoms like nausea and diarrhea can be mistaken for benign food poisoning, delaying critical care.

Ultimately, surviving death cap poisoning requires a race against time and a strategic use of these interventions. While activated charcoal and penicillin are widely accessible and relatively low-risk, liver transplants remain the most definitive yet resource-intensive option. Awareness of these treatments, coupled with immediate medical attention, can tip the scales in favor of survival. No single intervention guarantees success, but together, they offer a fighting chance against one of nature’s deadliest poisons.

Why McDonald's Mushroom & Swiss Burger Disappeared: A Fan's Lament

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.04 $29.99

Misidentification Risks: Resembles edible mushrooms like straw mushrooms, increasing accidental ingestion

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a silent assassin in the forest, often mistaken for its benign counterparts like straw mushrooms (*Volvariella volvacea*). This misidentification is not just a trivial error—it’s a life-threatening mistake. The death cap’s resemblance to edible species is so striking that even experienced foragers can be fooled. Its creamy white gills, greenish-yellow cap, and bulbous base mimic the harmless straw mushroom, especially in younger stages. This visual deception is compounded by habitat overlap; both species thrive in similar environments, often near trees in temperate regions. The result? Accidental ingestion is alarmingly common, with symptoms like severe abdominal pain, liver failure, and even death appearing within 6–24 hours post-consumption.

To avoid this fatal error, foragers must adopt a meticulous approach. First, examine the mushroom’s base—straw mushrooms have a delicate, sack-like volva that is easily detachable, while death caps have a cup-like volva that is more persistent. Second, cut the mushroom in half; straw mushrooms have a smooth, even stem, whereas death caps often have a jagged, skirt-like ring. Third, consider the spore color—straw mushrooms produce pink spores, while death caps produce white. These distinctions are critical, as even a small fragment of a death cap can contain enough amatoxins to cause severe harm. Foraging without proper knowledge is akin to playing Russian roulette with nature.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to misidentification risks. A single death cap mushroom contains enough toxins to kill an adult, and smaller bodies are even more susceptible. Teach children never to touch or taste wild mushrooms, and keep pets on a leash in areas where mushrooms grow. If accidental ingestion is suspected, immediate medical attention is non-negotiable. Activated charcoal may be administered to reduce toxin absorption, but time is of the essence—amatoxins can cause irreversible liver damage within hours. Prevention, however, remains the best strategy. Invest in a reliable field guide, join local mycological societies, and always verify findings with an expert before consumption.

The allure of wild foraging is undeniable, but it demands respect for the fine line between nourishment and poison. The death cap’s deceptive appearance serves as a stark reminder that nature’s beauty often conceals danger. By understanding its distinguishing features and adopting cautious practices, foragers can enjoy the bounty of the forest without risking their lives. Misidentification is not inevitable—it’s a preventable tragedy that hinges on knowledge, vigilance, and humility in the face of nature’s complexity.

Can Mushrooms Really Grow Overnight? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Survival Rates: Early treatment improves chances, but fatality rates remain high without intervention

The death cap mushroom, or *Amanita phalloides*, is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings globally. Its toxins, primarily amatoxins, cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure. Survival hinges on one critical factor: time. The sooner treatment begins, the better the chances of recovery, but delays can be fatal. Without intervention, the fatality rate for death cap poisoning is alarmingly high, estimated at 10-50%.

Immediate Steps to Improve Survival

If ingestion is suspected, act within the first 6-12 hours. Induce vomiting to expel toxins, but only if the person is conscious and alert. Administer activated charcoal, available over the counter, to bind remaining toxins in the stomach. Seek emergency medical care immediately. Hospitals may use gastric lavage (stomach pumping) or administer intravenous fluids to stabilize the patient. Early treatment with silibinin, a milk thistle derivative, has shown promise in reducing liver damage by inhibiting toxin uptake.

The Role of Age and Dosage in Outcomes

Children and the elderly are at higher risk due to their lower body mass and weaker immune systems. Even a small cap (10-20 grams) can be lethal for a child, while an adult might require 50 grams or more. However, toxicity varies by mushroom, and symptoms often don’t appear for 6-24 hours, leading to delayed treatment. This latency period is deceptive, as it lulls victims into a false sense of security before organ failure begins.

Comparing Intervention vs. No Intervention

With prompt medical care, survival rates jump to 70-90%. Treatment protocols include liver support, such as N-acetylcysteine to counteract toxin effects, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation. Without intervention, the body’s organs deteriorate rapidly. By the time symptoms like jaundice, seizures, or coma appear, the damage is often irreversible. Historical data shows that untreated cases have a fatality rate exceeding 50%, underscoring the urgency of early action.

Practical Tips for Prevention and Response

Avoid foraging for wild mushrooms unless you’re an expert. Even experienced foragers mistake death caps for edible varieties like the paddy straw mushroom. If in doubt, consult a mycologist or use a mushroom identification app. Keep a first-aid kit with activated charcoal and contact poison control immediately if ingestion is suspected. Remember, the clock starts ticking the moment the mushroom is consumed—every minute counts in the fight for survival.

Rehydrating Hen of the Woods Mushrooms: Tips and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Survival is possible if medical treatment is sought immediately, but it is extremely dangerous. The death cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides) contains toxins that cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to death if untreated.

Symptoms typically appear 6–24 hours after ingestion and include abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, and jaundice. Later stages may involve liver and kidney failure, which can be fatal.

Treatment includes gastric decontamination, activated charcoal, and supportive care. Intravenous fluids, medications to protect the liver, and, in severe cases, a liver transplant may be necessary for survival.