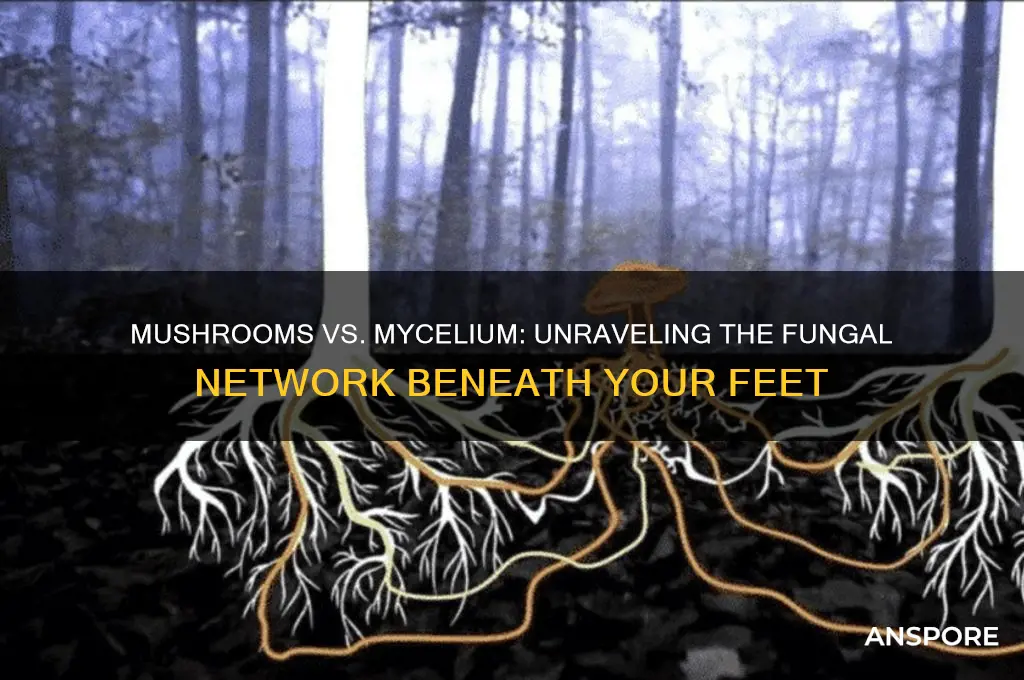

Mushrooms and mycelium are both integral parts of the fungal kingdom, yet they serve distinct roles and exhibit different characteristics. While mushrooms are the visible, fruiting bodies that emerge above ground, often recognized for their caps and stems, mycelium is the hidden, underground network of thread-like structures called hyphae that form the fungus's vegetative growth. Understanding the difference between these two is crucial, as mushrooms are typically associated with spore production and dispersal, whereas mycelium focuses on nutrient absorption and colonization. This distinction not only highlights the complexity of fungal life cycles but also underscores the importance of both components in ecosystems, agriculture, and even medicinal applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Visible Structure | Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies (reproductive structures) that emerge above ground, while mycelium is the underground network of thread-like filaments (hyphae) that forms the vegetative part of the fungus. |

| Function | Mushrooms produce and disperse spores for reproduction, whereas mycelium absorbs nutrients, grows, and supports the fungus's life cycle. |

| Appearance | Mushrooms are typically umbrella-shaped with a cap and stem, while mycelium appears as a white, cobweb-like mass or network of threads. |

| Location | Mushrooms grow above ground or on surfaces, while mycelium thrives beneath the soil, in wood, or other substrates. |

| Lifespan | Mushrooms are short-lived (days to weeks), whereas mycelium can persist for years or even centuries. |

| Role in Ecosystem | Mushrooms aid in spore dispersal and decomposition, while mycelium breaks down organic matter and forms symbiotic relationships with plants. |

| Edibility | Some mushrooms are edible, while mycelium is generally not consumed directly (though it can be grown for supplements or food products like mycelium-based meat alternatives). |

| Growth Rate | Mushrooms grow rapidly during fruiting, while mycelium grows slowly and steadily over time. |

| Composition | Mushrooms consist of dense fungal tissue, while mycelium is a network of thin, branching hyphae. |

| Detection | Mushrooms are easily visible, while mycelium requires careful observation or excavation to detect. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Visual Differences: Mushrooms are visible fruiting bodies; mycelium is a hidden, thread-like network underground

- Function Comparison: Mushrooms disperse spores; mycelium absorbs nutrients and supports growth

- Life Cycle Role: Mushrooms are reproductive; mycelium is the vegetative, sustaining part

- Texture and Form: Mushrooms are solid and fleshy; mycelium is fibrous and web-like

- Habitat and Growth: Mushrooms appear above ground; mycelium thrives in soil or substrates

Visual Differences: Mushrooms are visible fruiting bodies; mycelium is a hidden, thread-like network underground

Mushrooms and mycelium are both integral parts of the fungal kingdom, yet their appearances differ dramatically. Mushrooms, the visible fruiting bodies, emerge above ground as distinct structures—caps, stems, and gills—that are easily identifiable to the naked eye. In contrast, mycelium operates in secrecy, forming a dense, thread-like network of filaments called hyphae that sprawl beneath the soil or within decaying matter. This hidden infrastructure is the lifeblood of the fungus, absorbing nutrients and sustaining growth, while mushrooms serve primarily as reproductive organs, releasing spores to propagate the species.

To distinguish the two visually, consider their roles and environments. Mushrooms are ephemeral, appearing seasonally in forests, lawns, or cultivated beds, often after rain or in humid conditions. Their shapes, colors, and textures vary widely—from the iconic umbrella-like portobello to the delicate, lacy structures of coral fungi. Mycelium, however, is rarely seen without deliberate excavation or laboratory cultivation. When exposed, it resembles a white, cobweb-like mat or a clump of fine roots, sometimes visible in decomposing wood or as a thin layer beneath the soil. This contrast in visibility underscores their functional differences: mushrooms are designed to be noticed, while mycelium thrives in obscurity.

For practical identification, focus on context. If you spot a conspicuous, above-ground structure with a cap and stem, it’s a mushroom. If you’re examining soil or decaying material and find a network of tiny, branching threads, you’re likely observing mycelium. Gardeners and foragers can use this knowledge to assess soil health—abundant mycelium indicates robust fungal activity, which aids nutrient cycling and plant growth. Conversely, the presence of mushrooms signals spore dispersal, a fleeting but vital phase in the fungal life cycle.

A cautionary note: while mushrooms are visible and often edible, not all are safe to consume. Mycelium, though less accessible, is generally non-toxic but lacks culinary or medicinal value in its raw form. Always verify mushroom species before consumption, and avoid disturbing mycelium networks, as they play a critical role in ecosystem stability. Understanding these visual and functional differences empowers both casual observers and enthusiasts to appreciate the dual nature of fungi—one part showy, the other stealthy, yet both indispensable.

Moldy Shiitake Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Toss Them Out?

You may want to see also

Function Comparison: Mushrooms disperse spores; mycelium absorbs nutrients and supports growth

Mushrooms and mycelium, though interconnected, serve distinct roles in the fungal life cycle. Mushrooms, the visible fruiting bodies, are primarily spore factories. Their gills, pores, or teeth are designed to release billions of spores into the environment, ensuring the fungus’s genetic material travels far and wide. This dispersal mechanism is akin to a plant’s seeds, but on a microscopic scale. For instance, a single mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in a day, highlighting their efficiency in propagation. Without this function, fungi would struggle to colonize new habitats or recover from disturbances.

In contrast, mycelium operates behind the scenes as the fungus’s nutrient acquisition and growth support system. This network of thread-like structures, called hyphae, secretes enzymes to break down organic matter—wood, soil, or decaying leaves—into absorbable nutrients. Mycelium can cover vast areas, with some networks spanning acres, making it one of nature’s most efficient recyclers. For example, oyster mushroom mycelium can decompose straw in weeks, converting it into a nutrient-rich substrate. This dual role of absorption and structural support is critical for the fungus’s survival and the ecosystem’s health.

To illustrate the functional divide, consider a practical scenario: cultivating mushrooms at home. Growers inoculate substrates like sawdust or grain with mycelium, which then colonizes the material over weeks, absorbing nutrients and preparing for fruiting. Once conditions are right—adequate humidity, light, and temperature—mushrooms emerge, their primary purpose being spore dispersal. This process underscores the symbiotic relationship: mycelium sustains growth, while mushrooms ensure future generations. For optimal results, maintain substrate moisture at 50-60% and fruiting chamber humidity at 85-95%.

From an ecological perspective, this division of labor is a masterclass in efficiency. Mycelium’s nutrient absorption supports not only the fungus but also surrounding plants by enhancing soil fertility and facilitating nutrient exchange. Mushrooms, meanwhile, contribute to biodiversity by dispersing spores that can colonize new areas. This dual functionality explains why fungi are keystone species in many ecosystems. For gardeners, incorporating mycelium-rich compost can improve soil structure and nutrient availability, while planting mushrooms in shaded, moist areas encourages spore dispersal and fungal diversity.

In summary, while mushrooms and mycelium are inseparable, their functions are specialized and complementary. Mushrooms act as reproductive agents, dispersing spores to propagate the species, while mycelium functions as the metabolic powerhouse, absorbing nutrients and supporting growth. Understanding this distinction not only deepens appreciation for fungal biology but also informs practical applications, from cultivation to ecological restoration. Whether you’re a hobbyist grower or an environmental enthusiast, recognizing these roles allows you to harness the unique capabilities of each.

Mushroom Compost Risks: Worms, Parasites, and Garden Safety Explained

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Role: Mushrooms are reproductive; mycelium is the vegetative, sustaining part

Mushrooms and mycelium are two distinct yet interconnected parts of the fungal life cycle, each playing a unique role in the organism's survival and propagation. While mushrooms are the visible, fruiting bodies that emerge from the substrate, mycelium is the hidden, thread-like network that forms the foundation of the fungus. Understanding their life cycle roles is crucial for anyone interested in cultivation, foraging, or simply appreciating the complexity of these organisms.

From an analytical perspective, the mushroom's primary function is reproductive. It produces and disperses spores, which are akin to fungal seeds, ensuring the continuation of the species. These spores are released into the environment, often in vast quantities, and can travel through air, water, or animal vectors to colonize new habitats. In contrast, mycelium serves as the vegetative, sustaining part of the fungus, responsible for nutrient absorption, growth, and energy storage. This underground network can span vast areas, sometimes covering acres, and can live for decades or even centuries, making it one of the most resilient and long-lived organisms on Earth.

To illustrate the practical implications of these roles, consider mushroom cultivation. Growers focus on creating optimal conditions for mycelium to thrive, as a healthy mycelial network is essential for fruiting. This involves maintaining proper humidity, temperature, and substrate composition. Once the mycelium is well-established, it can be induced to produce mushrooms through environmental triggers like changes in light, temperature, or carbon dioxide levels. For example, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) typically fruit when the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate and is exposed to fresh air and higher light levels. Understanding this process allows cultivators to manipulate the environment, encouraging the mycelium to allocate resources toward mushroom production.

A comparative analysis highlights the symbiotic relationship between mushrooms and mycelium. While mushrooms are short-lived and ephemeral, mycelium is persistent and enduring. This duality reflects the fungus's strategy for survival: the mycelium ensures long-term sustenance and adaptability, while mushrooms facilitate rapid reproduction and dispersal. For foragers, this distinction is critical. Identifying mushrooms requires knowledge of their visible characteristics, such as cap shape, gill structure, and spore color. In contrast, mycelium is often identified indirectly, through its effects on the substrate, such as wood decay or soil aggregation. For instance, the presence of white, fibrous material in decomposing logs indicates active mycelium, even if no mushrooms are visible.

Finally, a persuasive argument can be made for the importance of preserving both mushrooms and mycelium in ecosystems. Mushrooms contribute to nutrient cycling by breaking down organic matter and releasing minerals back into the soil. Mycelium, with its extensive network, enhances soil structure, promotes plant growth through mycorrhizal relationships, and even filters toxins. For example, certain mycelium species are used in mycoremediation to clean up oil spills and contaminated soil. By protecting these organisms, we support biodiversity, improve soil health, and address environmental challenges. Whether you're a cultivator, forager, or conservationist, recognizing the distinct life cycle roles of mushrooms and mycelium is key to harnessing their potential and ensuring their survival.

Can Dogs Hallucinate? Mushroom Risks and Symptoms to Watch For

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

Texture and Form: Mushrooms are solid and fleshy; mycelium is fibrous and web-like

Mushrooms and mycelium, though interconnected, present starkly different physical characteristics that make them distinguishable to the naked eye. The mushroom, the fruiting body of the fungus, is solid and fleshy, often with a distinct cap and stem. This structure is designed for spore dispersal, making it a visible and tangible entity in the forest or garden. In contrast, mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, is a network of thread-like filaments called hyphae. This fibrous, web-like structure is hidden beneath the soil or within organic matter, serving as the organism’s nutrient absorption system. Understanding these differences is crucial for foragers, cultivators, and enthusiasts alike.

To identify mushrooms in the wild, focus on their texture and form. A mature mushroom typically feels firm yet yielding, akin to a ripe fruit. Its shape is often symmetrical, with a cap that may be smooth, gilled, or porous, and a stem that supports it. For example, the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) has a smooth, white cap and a sturdy stem, while the lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) has a shaggy, icicle-like appearance. When harvesting, ensure the mushroom is fully mature but not overripe, as older specimens may become slimy or discolored. Always cut the stem at the base to avoid damaging the mycelium below, allowing it to continue growing.

Mycelium, on the other hand, requires a different approach to identification and handling. Its fibrous, web-like texture is best observed in cultivated environments, such as in mushroom grow kits or laboratory settings. When inoculating substrate with mycelium, ensure even distribution to promote healthy growth. For instance, in oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) cultivation, mycelium is often mixed into straw or sawdust, where its network can efficiently break down the material. Avoid compacting the substrate too tightly, as this can restrict the mycelium’s ability to spread. Patience is key, as mycelium growth can take weeks before fruiting bodies emerge.

The contrast between mushrooms and mycelium extends to their practical applications. Mushrooms are prized for their culinary and medicinal properties, with specific textures influencing their use. For example, the meaty texture of portobello mushrooms makes them ideal for grilling, while the delicate flesh of enoki mushrooms is perfect for soups. Mycelium, however, is gaining attention in sustainable industries, such as packaging and leather alternatives, due to its fibrous strength and biodegradability. Companies like Ecovative Design use mycelium to create compostable packaging, showcasing its potential beyond food production.

In summary, the texture and form of mushrooms and mycelium are not just distinguishing features but also indicators of their function and utility. By recognizing the solid, fleshy structure of mushrooms and the fibrous, web-like nature of mycelium, individuals can better appreciate their roles in ecosystems and human applications. Whether foraging, cultivating, or innovating, this knowledge empowers informed and sustainable practices.

Mushrooms on a Yeast-Free Diet: Safe or Off-Limits?

You may want to see also

Habitat and Growth: Mushrooms appear above ground; mycelium thrives in soil or substrates

Mushrooms and mycelium, though interconnected, inhabit distinct realms within their ecosystem. Mushrooms, the fruiting bodies we often see, emerge above ground, their caps and stems breaking through soil, wood, or other substrates. This above-ground appearance is a strategic move for spore dispersal, as it allows wind, water, and animals to carry spores to new locations. In contrast, mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—operates beneath the surface, forming a dense network of thread-like structures called hyphae. This subterranean lifestyle enables mycelium to absorb nutrients, decompose organic matter, and establish a robust foundation for fungal growth.

To understand their habitats better, consider the analogy of an iceberg. The mushroom is the visible tip, while the mycelium is the vast, hidden mass below. Mycelium thrives in dark, moist environments, often within soil, decaying wood, or even compost. It requires a substrate rich in organic material to sustain its metabolic processes. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) grow on dead or dying trees, their mycelium breaking down lignin and cellulose. In cultivation, mycelium is often grown on substrates like straw, sawdust, or grain, which are sterilized to prevent contamination and provide a nutrient-rich base.

Practical tips for distinguishing their habitats include observing where mushrooms appear. If you spot mushrooms in your garden, they’re likely growing where mycelium has colonized the soil or mulch. Foraging enthusiasts should note that mushrooms in wooded areas often indicate mycelium networks within fallen logs or leaf litter. To cultivate mushrooms at home, focus on creating a suitable substrate for mycelium. For example, shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) require hardwood logs inoculated with mycelium, while button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) thrive in composted manure.

A comparative analysis reveals the symbiotic relationship between mushrooms and mycelium. While mushrooms are transient, appearing only under specific conditions (e.g., adequate moisture and temperature), mycelium persists year-round, silently working to decompose and recycle nutrients. This duality highlights their ecological roles: mushrooms as reproductive agents and mycelium as the primary nutrient gatherers. Understanding this distinction is crucial for both mycologists and hobbyists, as it informs techniques for cultivation, conservation, and even medicinal applications, such as using mycelium-based products for soil remediation or immune support.

In conclusion, the habitats of mushrooms and mycelium are as distinct as their functions. Mushrooms’ above-ground presence serves reproduction, while mycelium’s subterranean network sustains growth and nutrient cycling. By recognizing these differences, one can better appreciate the complexity of fungal ecosystems and apply this knowledge to practical endeavors, from gardening to gourmet mushroom cultivation. Whether you’re a forager, farmer, or fungi enthusiast, understanding these habitats unlocks a deeper connection to the hidden world beneath our feet.

Medicines That Interact with Mushrooms: Potential Risks and Precautions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A mushroom is the fruiting body of a fungus, visible above ground, while mycelium is the underground network of thread-like structures (hyphae) that absorb nutrients.

Mycelium is often too fine to see without magnification, though it may appear as a white, cobweb-like mass in soil or on decaying material.

Yes, all mushrooms are produced by mycelium, which is the vegetative part of the fungus responsible for growth and nutrient absorption.

Yes, mycelium can grow and spread without forming mushrooms, especially if environmental conditions (like light, humidity, or temperature) are not ideal for fruiting.

Mycelium often appears as white, thread-like structures in soil, wood, or compost. It may also form a dense, mat-like layer beneath the surface.