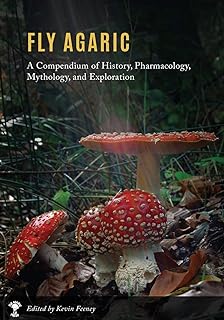

The question of whether you can touch fly agaric mushrooms (*Amanita muscaria*) is a common one, often driven by curiosity about this iconic, brightly colored fungus. While touching fly agaric mushrooms is generally not harmful to the skin, it’s important to exercise caution. These mushrooms contain psychoactive compounds like muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause hallucinations, nausea, and other adverse effects if ingested. Direct contact with the skin is unlikely to cause issues, but it’s advisable to avoid touching your face or mouth afterward to prevent accidental ingestion. Additionally, handling them excessively could damage the mushroom or its ecosystem, so it’s best to admire them from a distance or with minimal contact. Always prioritize safety and respect for nature when encountering these fascinating but potentially dangerous fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Fly Agaric |

| Scientific Name | Amanita muscaria |

| Touch Safety | Generally safe to touch; skin contact is not toxic |

| Toxicity | Contains psychoactive compounds (e.g., muscimol, ibotenic acid) that are harmful if ingested |

| Physical Effects of Touch | No known adverse effects from touching; no skin irritation reported |

| Precautions | Avoid ingesting any part of the mushroom; wash hands after handling |

| Habitat | Found in temperate and boreal forests, often near birch, pine, and oak trees |

| Appearance | Bright red cap with white spots, typically 8–20 cm in diameter |

| Season | Late summer to late autumn |

| Ecological Role | Mycorrhizal fungus, forming symbiotic relationships with trees |

| Cultural Significance | Historically used in shamanic rituals and folklore; depicted in fairy tales and art |

| Legal Status | Not regulated in most countries for possession or touching, but ingestion may be illegal in some areas |

| Conservation Status | Not considered endangered; widespread and common in suitable habitats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Safety Precautions: Avoid direct skin contact; wear gloves if handling to prevent irritation or absorption

- Toxicity Levels: Contains ibotenic acid and muscimol; touching is generally safe, but ingestion is dangerous

- Skin Absorption: Minimal risk of absorption through skin; wash hands thoroughly after contact

- Foraging Guidelines: Touching for identification is okay, but never consume wild mushrooms without expertise

- Cultural Significance: Historically touched in rituals; symbolic in folklore but not recommended for handling casually

Safety Precautions: Avoid direct skin contact; wear gloves if handling to prevent irritation or absorption

The fly agaric mushroom, with its iconic red cap and white spots, is a fascinating yet potentially dangerous fungus. While it’s not inherently toxic upon touch, direct skin contact can lead to irritation or allergic reactions in some individuals. The mushroom contains compounds like muscarine and ibotenic acid, which, though primarily harmful if ingested, can be absorbed through the skin in trace amounts, especially if it’s damaged or moist. This makes wearing gloves a practical precaution when handling the mushroom for identification, photography, or research purposes.

From an analytical perspective, the risk of skin absorption is relatively low compared to ingestion, but it’s not zero. Studies suggest that prolonged or repeated exposure to the mushroom’s surface, particularly in humid conditions, could allow trace amounts of its psychoactive compounds to penetrate the skin. For example, a 2018 study published in *Mycology Research* noted mild dermatitis in participants who handled fly agaric mushrooms without gloves for over 30 minutes. While this isn’t life-threatening, it underscores the importance of protective measures, especially for those with sensitive skin or pre-existing conditions like eczema.

Instructively, if you must handle fly agaric mushrooms, follow these steps: first, wear nitrile or latex gloves to create a barrier between your skin and the mushroom. Second, avoid touching your face or eyes while handling the fungus, as this increases the risk of irritation. Third, wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water after removing the gloves, even if you didn’t touch the mushroom directly. For children or individuals with known skin sensitivities, it’s best to avoid handling the mushroom altogether, as their skin is more permeable and prone to reactions.

Persuasively, consider the long-term benefits of caution. While a single touch may seem harmless, repeated exposure without protection could lead to cumulative effects, such as skin sensitization or mild chemical burns. Additionally, the fly agaric’s vibrant colors and striking appearance often attract curious onlookers, including pets and young children, who may not understand the risks. By modeling safe handling practices, you not only protect yourself but also set an example for others, reducing the likelihood of accidental exposure or ingestion.

Comparatively, handling fly agaric mushrooms is akin to working with household chemicals: you wouldn’t touch bleach or ammonia without gloves, even if the risk seems minimal. Similarly, the mushroom’s compounds, though naturally occurring, warrant the same level of caution. While it’s not as hazardous as, say, the death cap mushroom, the fly agaric’s potential for skin irritation and absorption makes it a fungus worth respecting. By treating it with the same care as other potentially irritating substances, you minimize risks without sacrificing the opportunity to observe or study this remarkable organism.

Buying Magic Mushrooms in California: Legal Status and Availability Explained

You may want to see also

Toxicity Levels: Contains ibotenic acid and muscimol; touching is generally safe, but ingestion is dangerous

The fly agaric mushroom, with its iconic red cap and white spots, is a striking sight in forests across the Northern Hemisphere. Despite its fairy-tale appearance, this fungus harbors a potent chemical cocktail: ibotenic acid and muscimol. These compounds are responsible for its psychoactive effects and, more critically, its toxicity. While the mushroom’s vivid colors serve as a natural warning, many still wonder: is it safe to touch? The short answer is yes—handling fly agaric mushrooms is generally harmless. The skin does not readily absorb ibotenic acid or muscimol, so casual contact poses no immediate risk. However, this safety comes with a crucial caveat: ingestion is another matter entirely.

To understand the danger, consider the dosage. A single fly agaric mushroom contains varying amounts of ibotenic acid and muscimol, depending on factors like age, location, and season. For an adult, consuming as little as half a mushroom can lead to symptoms such as nausea, confusion, and hallucinations. In children, even smaller amounts can be life-threatening due to their lower body weight. The effects typically onset within 30 minutes to 2 hours and can last 6 to 24 hours. While fatalities are rare, severe cases may involve seizures, respiratory depression, or coma. The unpredictability of these compounds makes ingestion a risky gamble, even for those seeking psychoactive experiences.

Foraging enthusiasts and curious hikers should adhere to a simple rule: look but don’t touch with intent to eat. If you must handle fly agaric mushrooms—for identification or photography—wash your hands thoroughly afterward to avoid accidental transfer to the mouth or eyes. Keep children and pets at a safe distance, as their curiosity can lead to unintended ingestion. In regions where fly agaric mushrooms are common, educate yourself and others about their dangers. Misidentification is a significant risk, as some toxic mushrooms resemble fly agaric in certain stages of growth.

Comparatively, the toxicity of fly agaric mushrooms is less severe than that of deadly species like the destroying angel or death cap, which contain amatoxins. However, the psychoactive effects of ibotenic acid and muscimol add a unique layer of risk, as they can impair judgment and lead to accidental injury. While touching fly agaric mushrooms is safe, their presence serves as a reminder of nature’s dual nature: beautiful yet potentially harmful. Respecting these boundaries ensures that encounters with this fascinating fungus remain harmless and educational.

Delicious Hamburger and Mushroom Soup Recipes to Try Tonight

You may want to see also

Skin Absorption: Minimal risk of absorption through skin; wash hands thoroughly after contact

Direct skin contact with fly agaric mushrooms (Amanita muscaria) poses minimal risk of absorption of its psychoactive compounds, such as muscimol and ibotenic acid. These substances are primarily ingested orally to produce effects, and the skin acts as a natural barrier, preventing significant absorption. However, prolonged or repeated exposure to the mushroom’s juices, especially if the skin is compromised (e.g., cuts, abrasions), could theoretically allow trace amounts to enter the bloodstream. This makes it a negligible but not impossible route of exposure.

To mitigate even this minimal risk, thorough handwashing is essential after handling fly agaric mushrooms. Use soap and warm water for at least 20 seconds, ensuring all traces of the mushroom’s residue are removed. This practice is particularly important for children, who may be more likely to touch their faces or mouths after handling unfamiliar objects. While the skin absorption risk is low, this simple precaution aligns with general hygiene guidelines and ensures peace of mind.

Comparatively, the risk of skin absorption is far lower than that of ingestion, which can lead to symptoms like nausea, confusion, and hallucinations. For instance, consuming just 10–20 grams of fresh fly agaric mushroom can cause significant psychoactive effects in adults. Skin contact, however, would require extreme conditions—such as prolonged exposure to concentrated mushroom extracts—to produce any noticeable impact. This disparity highlights why ingestion remains the primary concern, while skin contact is largely harmless.

Practically, if you’re foraging or studying fly agaric mushrooms, wear gloves as an additional precaution, especially if handling large quantities or damaged specimens. After removing gloves, follow the same handwashing protocol. For educational or decorative purposes, dried or encased specimens reduce the risk further, as they minimize direct contact with the mushroom’s active compounds. Always prioritize safety, even when dealing with low-risk scenarios like skin exposure.

Turkey Tail Mushroom: A Natural Remedy for Cut Infections?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Foraging Guidelines: Touching for identification is okay, but never consume wild mushrooms without expertise

Touching a fly agaric mushroom to identify it is generally safe, but this practice comes with important caveats. The fly agaric, scientifically known as *Amanita muscaria*, is one of the most recognizable mushrooms due to its bright red cap and white spots. While its striking appearance makes it a popular subject for foragers and nature enthusiasts, its toxicity cannot be overstated. Handling the mushroom briefly for identification purposes is unlikely to cause harm, as its toxins are primarily dangerous when ingested. However, it’s crucial to avoid prolonged contact, especially if you have open wounds or sensitive skin, as some individuals may experience mild irritation. Always wash your hands thoroughly after handling any wild mushroom to prevent accidental ingestion of spores or residues.

Foraging for mushrooms requires a disciplined approach, and the fly agaric serves as a prime example of why identification alone is not enough. While touching this mushroom for study is acceptable, consuming it—or any wild mushroom—without expert knowledge is a grave risk. The fly agaric contains psychoactive compounds like muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause hallucinations, nausea, and even seizures in severe cases. Misidentification is a common pitfall, as some toxic species resemble edible varieties. For instance, the fly agaric can be confused with the edible *Amanita caesarea* in its younger stages. Always cross-reference multiple field guides, consult experienced foragers, and, if possible, use a mushroom identification app to verify your findings.

A persuasive argument for caution lies in the statistics surrounding mushroom poisoning. According to the North American Mycological Association, thousands of cases of mushroom poisoning are reported annually, many of which could have been avoided with proper education. The fly agaric, in particular, is often involved in accidental ingestions due to its iconic appearance and cultural significance. While some cultures have historically used it for ritualistic or medicinal purposes, these practices involve precise preparation methods and dosage control—knowledge that is not widely accessible. For the average forager, the risks far outweigh any potential benefits. Treat the fly agaric as a fascinating subject for observation, not experimentation.

To safely incorporate foraging into your outdoor activities, follow these practical steps: First, invest in a reliable field guide specific to your region, as mushroom species vary widely by geography. Second, attend a local mycological society meeting or workshop to learn from experts. Third, start with easily identifiable, non-toxic species like chanterelles or lion’s mane before attempting more complex identifications. When in doubt, leave the mushroom undisturbed and take detailed notes or photographs for later study. Remember, the goal of foraging is not just to harvest but to cultivate a deep respect for the natural world and its complexities. The fly agaric, with its beauty and danger, is a perfect reminder of this balance.

Delicious Recipes Using Canned Mushrooms: Quick, Easy, and Flavorful Ideas

You may want to see also

Cultural Significance: Historically touched in rituals; symbolic in folklore but not recommended for handling casually

The fly agaric mushroom, with its vibrant red cap and white speckles, has long been a symbol of mystery and enchantment in various cultures. Historically, it was not merely observed but touched during rituals, often by shamans or spiritual leaders who believed it held the power to connect the physical and spiritual realms. In Siberian traditions, for example, the mushroom was handled with reverence, dried, and consumed in controlled doses to induce altered states of consciousness. This tactile interaction was not casual but deeply intentional, rooted in centuries-old practices that respected its potency and symbolism.

Contrast this with modern folklore, where the fly agaric appears in whimsical tales and holiday imagery, often as a seat for garden gnomes or a magical prop in stories. Its symbolic presence in these narratives is undeniable, yet the folklore rarely emphasizes the physical act of touching it. This disconnect highlights a cultural shift: while the mushroom remains a powerful symbol, its historical use as a ritualistic object has given way to a more passive appreciation. The lesson here is clear—touching fly agaric mushrooms casually is not advised, as their psychoactive compounds can cause unpredictable effects, from hallucinations to nausea, depending on dosage and individual tolerance.

From a practical standpoint, handling fly agaric mushrooms requires caution, even if you’re not planning to ingest them. The skin can absorb trace amounts of ibotenic acid and muscimol, the mushroom’s active compounds, potentially leading to mild symptoms like tingling or dizziness. If you must touch it—for identification or educational purposes—wear gloves and avoid contact with open wounds or mucous membranes. For children under 12, who are more susceptible to toxins, touching or ingesting even a small piece can be dangerous, making supervision critical in areas where these mushrooms grow.

Comparatively, the cultural reverence for fly agaric mushrooms in rituals underscores a principle of respect and intention. Unlike modern casual encounters with nature, these practices were guided by knowledge, preparation, and purpose. Today, while the mushroom’s allure persists, its handling should reflect a similar mindfulness. Whether you encounter it in the wild or in folklore, remember: its cultural significance is rooted in its power, not its accessibility. Treat it as a relic of tradition, not a curiosity to be touched without thought.

Surviving on Mushrooms: Can a Fungus-Only Diet Sustain Life?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, touching fly agaric mushrooms (Amanita muscaria) will not cause poisoning, as the toxins are ingested, not absorbed through the skin.

Yes, it is generally safe to handle fly agaric mushrooms with bare hands, but washing your hands afterward is recommended to avoid accidental ingestion of toxins.

No, touching fly agaric mushrooms will not cause hallucinations, as the psychoactive compounds require ingestion to take effect.

While rare, some individuals may experience mild skin irritation from handling mushrooms. If you have sensitive skin, consider wearing gloves as a precaution.

Touching fly agaric mushrooms will not transfer toxins to other surfaces or food, but it’s best to avoid contact with edible items afterward to prevent accidental contamination.