Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, is widely used in microbiology as a solidifying agent for culturing microorganisms. Its ability to provide a stable, nutrient-rich medium makes it a popular choice for cloning various fungi, including mushrooms. However, when it comes to cloning dry mushrooms, the process becomes more complex. Dry mushrooms lack the moisture and active mycelium necessary for immediate cultivation, requiring rehydration and careful preparation to revive the fungal material. While agar can serve as a growth medium once the mycelium is reactivated, success depends on factors such as the mushroom species, the condition of the dried material, and the sterilization techniques employed. Thus, using agar to clone dry mushrooms is feasible but demands precision and understanding of fungal biology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method | Agar cloning |

| Substrate | Dry mushrooms |

| Purpose | To isolate and propagate mycelium from dried mushroom tissue |

| Feasibility | Possible, but less reliable than fresh tissue |

| Success Rate | Lower compared to fresh mushrooms due to reduced viability of mycelium in dried tissue |

| Required Materials | Agar, Petri dishes, sterile tools, dried mushroom tissue |

| Sterilization | Critical to prevent contamination |

| Hydration | Dried tissue may need rehydration before inoculation |

| Contamination Risk | Higher due to potential dormant contaminants in dried mushrooms |

| Alternative Methods | Grain spawn, liquid culture, or using fresh tissue |

| Best Practices | Use high-quality agar, sterile technique, and select healthy dried mushrooms |

| Common Issues | Slow or no growth, contamination, tissue necrosis |

| Recommended Use | For preservation or when fresh tissue is unavailable |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Agar's role in mushroom cloning

Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, serves as a cornerstone in mushroom cloning due to its unique properties. Its ability to solidify at room temperature and remain stable at high temperatures makes it an ideal growth medium for fungi. Unlike other gelling agents, agar is inert, meaning it does not provide nutrients to microorganisms, which allows for the selective cultivation of the target mushroom mycelium. This characteristic is crucial when working with dry mushrooms, as it ensures that only the desired fungal species proliferates, minimizing contamination risks.

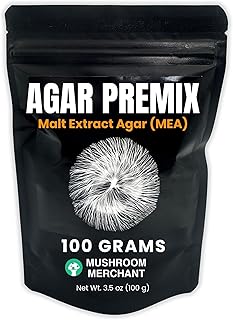

To clone dry mushrooms using agar, the process begins with rehydrating the mushroom tissue to reactivate its mycelium. Submerge the dry mushroom in sterile water for 20–30 minutes, ensuring it absorbs enough moisture without becoming waterlogged. Once rehydrated, carefully excise a small piece of the mushroom’s inner tissue, avoiding the outer surface to reduce the risk of contaminants. This tissue is then placed onto an agar plate prepared with a nutrient-rich medium, such as potato dextrose agar (PDA) or malt extract agar (MEA), which provides the essential nutrients for mycelial growth.

The role of agar in this process extends beyond merely providing a solid substrate. Its transparency allows cultivators to monitor mycelial growth and detect contaminants early. For optimal results, maintain the agar plates at a temperature of 22–26°C (72–78°F), as this range promotes rapid mycelial colonization. After 7–14 days, the mycelium should visibly spread across the agar surface, indicating successful cloning. At this stage, the mycelium can be transferred to a bulk substrate, such as grain or sawdust, to initiate fruiting.

While agar is indispensable for mushroom cloning, it is not without challenges. Contamination remains a significant risk, particularly when working with dry mushrooms, which may harbor dormant spores or bacteria. To mitigate this, sterilize all equipment and work in a clean environment, such as a still-air box or laminar flow hood. Additionally, using a pressure cooker to sterilize the agar medium at 15 psi for 30–45 minutes ensures a contamination-free base for mycelial growth.

In conclusion, agar’s role in mushroom cloning is multifaceted, offering a stable, observable, and controllable environment for mycelial propagation. When applied correctly, it enables cultivators to clone dry mushrooms with precision, paving the way for consistent and scalable mushroom cultivation. By understanding agar’s properties and following best practices, even novice mycologists can achieve successful cloning results.

Where to Buy Microdose Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Preparing agar plates for cloning

Agar plates are a cornerstone of mushroom cloning, offering a sterile, nutrient-rich environment for mycelium growth. Preparing them correctly is crucial for success, especially when working with dry mushrooms, which require careful rehydration and handling to ensure viable tissue transfer. The process begins with selecting the right agar formula, typically Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or Malt Extract Agar (MEA), both of which provide essential nutrients for fungal growth. Sterilization is paramount; all equipment, including Petri dishes, must be autoclaved at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to eliminate contaminants. Once cooled, the agar solution is poured into the dishes in a sterile environment, such as a laminar flow hood, to prevent airborne contamination.

Rehydrating dry mushrooms for cloning requires precision. Submerge the mushroom fragments in sterile distilled water for 10–15 minutes to revive the tissue without causing degradation. After rehydration, gently blot the fragments with a sterile paper towel to remove excess moisture, which can dilute the agar and introduce impurities. Using a flame-sterilized scalpel or blade, excise a small piece of tissue (ideally from the cap or stem) and place it onto the agar plate. Ensure the tool is cooled before contact with the agar to avoid damaging the medium. This step demands a steady hand and attention to detail, as contamination at this stage can ruin the entire process.

The incubation phase is critical for successful cloning. Agar plates should be stored in a dark, temperature-controlled environment, ideally at 22–26°C, to encourage mycelial growth. Monitor the plates daily for signs of contamination, such as mold or discoloration, and discard any compromised samples immediately. Healthy mycelium typically appears as white, thread-like structures radiating from the tissue fragment. After 7–14 days, the mycelium should be ready for transfer to a larger substrate, such as grain spawn or agar slants, for further propagation.

While agar cloning is effective, it’s not without challenges. Contamination remains the primary risk, particularly when working with dry mushrooms, which may harbor dormant spores or bacteria. To mitigate this, maintain strict aseptic technique throughout the process, including frequent disinfection of work surfaces and tools. Additionally, using a pressure cooker or autoclave for sterilization is non-negotiable, as boiling alone does not achieve the necessary level of sterility. For hobbyists, investing in a DIY laminar flow hood or still-air box can significantly improve success rates by minimizing airborne contaminants.

In conclusion, preparing agar plates for cloning dry mushrooms is a meticulous but rewarding process. By combining the right materials, sterile techniques, and careful handling, cultivators can reliably propagate mushroom cultures from dried tissue. While the method requires patience and precision, the ability to revive and clone mushrooms from a desiccated state opens up new possibilities for preservation and experimentation in mycology. With practice, even beginners can master this technique, unlocking the potential to grow a diverse array of mushroom species from minimal starting material.

Lion's Mane Mushrooms: A Potential Alzheimer's Disease Treatment?

You may want to see also

Sterilizing mushroom tissue for agar

Sterilizing mushroom tissue is a critical step in the agar cloning process, ensuring the removal of contaminants that could compromise the culture. The goal is to create a sterile environment where only the desired mushroom mycelium can thrive. This step is particularly challenging when working with dry mushrooms, as rehydration can introduce bacteria or other microorganisms. To begin, select a healthy, uncontaminated portion of the mushroom, typically the stem base or gill tissue, as these areas are less likely to harbor spores or external contaminants.

The sterilization process often involves a combination of physical and chemical methods. One effective technique is flame sterilization, where the scalpel or tissue forceps are passed through a flame to kill surface microorganisms. For the tissue itself, a common approach is to use a dilute solution of household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) or alcohol. A 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) can be used to soak the tissue for 1–2 minutes, followed by rinsing with sterile distilled water to remove any residual chemicals. Alternatively, a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution can be applied directly to the tissue for 30 seconds before transferring it to the agar plate.

While chemical sterilization is effective, it must be executed carefully to avoid damaging the mushroom tissue. Over-exposure to bleach or alcohol can kill the mycelium, rendering the cloning attempt futile. A key takeaway is to balance sterilization with tissue viability. After treatment, the tissue should be gently blotted dry on a sterile paper towel or filter paper to remove excess moisture, which can dilute the agar and hinder mycelial growth.

Comparing sterilization methods, autoclaving is the gold standard in laboratory settings but is impractical for home cultivators due to the specialized equipment required. For DIY setups, the bleach or alcohol method, combined with flame sterilization of tools, offers a reliable alternative. However, consistency and precision are crucial—even a small oversight can introduce contaminants. For example, using non-sterile water for rinsing or failing to flame tools can undo the entire process.

In practice, sterilizing dry mushroom tissue for agar cloning requires attention to detail and a sterile workflow. Work in a clean environment, ideally with a still air box or laminar flow hood to minimize airborne contaminants. Label all sterile materials clearly to avoid cross-contamination, and always assume that any unsterilized surface or tool is a potential source of contamination. With patience and adherence to these steps, even dry mushrooms can be successfully cloned on agar, opening up possibilities for preserving rare or unique strains.

Deadly Mushrooms: Identifying Toxic Fungi That Can Kill Your Dog

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Transferring mycelium to agar

The success of this process hinges on the agar’s ability to provide a nutrient-rich, sterile environment conducive to mycelial growth. Agar plates are typically prepared using a mixture of malt extract, dextrose, and agar powder, sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C for 15–20 minutes. Once cooled, the agar should be solid but not overly firm, allowing the mycelium to spread easily. After transferring the mushroom fragment, seal the plate with parafilm or lab tape and incubate it in a dark, temperature-controlled environment (22–26°C) for 7–14 days. Monitor for signs of contamination, such as mold or discoloration, which may require discarding the plate.

One challenge in transferring mycelium from dried mushrooms is the low moisture content, which can hinder initial growth. To mitigate this, some cultivators rehydrate the mushroom tissue in sterile water or a nutrient solution for 1–2 hours before inoculation. However, this step must be performed under sterile conditions to avoid introducing bacteria or competing fungi. Alternatively, using a more nutrient-dense agar formulation, such as potato dextrose agar (PDA), can enhance the mycelium’s ability to revive and colonize the medium.

Once the mycelium has visibly grown on the agar, it can be subcultured to new plates or transferred to grain spawn for fruiting. This step ensures the strain’s longevity and allows for further experimentation or cultivation. For long-term storage, agar plates can be sealed in plastic bags and refrigerated at 4°C, where they remain viable for several months. This method not only preserves the genetic integrity of the mushroom strain but also provides a foundation for advanced techniques like tissue culture and genetic analysis.

In summary, transferring mycelium to agar from dried mushrooms is a meticulous but rewarding process that combines sterile technique with an understanding of fungal biology. By carefully selecting tissue, using properly prepared agar, and maintaining optimal conditions, cultivators can successfully revive and propagate specific strains. This technique is invaluable for mycologists, hobbyists, and commercial growers seeking to preserve rare or desirable mushroom genetics for future use.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Trees That Attract These Elusive Fungi

You may want to see also

Maintaining agar cultures long-term

Agar cultures are a cornerstone for mycologists and hobbyists seeking to preserve and propagate mushroom strains, but their longevity hinges on meticulous care. Long-term maintenance requires a balance of sterility, environmental control, and periodic subculturing. Unlike short-term projects, these cultures demand a proactive approach to prevent contamination and genetic drift. For instance, storing agar plates at 4°C (39°F) in sealed containers can extend viability for 6–12 months, but this is not indefinite. Humidity levels must be monitored to prevent desiccation, and plates should be inspected monthly for signs of mold or bacterial growth.

Subculturing is the lifeblood of long-term agar culture preservation. Every 3–6 months, transfer a small, healthy portion of the mycelium to fresh agar plates using sterile technique. This process rejuvenates the culture and reduces the risk of degeneration. Use a flame-sterilized inoculation loop or scalpel to extract the sample, and work in a still air box or laminar flow hood to minimize contamination. For added security, maintain backup cultures in separate containers or even different locations to safeguard against total loss.

Environmental stability is equally critical. Fluctuations in temperature or light exposure can stress the mycelium, accelerating degradation. Store cultures in a dark, temperature-controlled environment, and avoid frequent handling. Label each plate with the strain name, date, and subculture generation to track lineage and viability. For dry mushroom clones, ensure the original genetic material is robust before transferring to agar, as weak or degraded tissue may not thrive long-term.

Innovative techniques can further enhance preservation. Cryopreservation, though more complex, offers near-indefinite storage by freezing mycelium in liquid nitrogen or glycerol solutions. Alternatively, slant cultures—where agar is solidified at an angle—reduce surface area exposure, minimizing contamination risk. For hobbyists, simpler methods like parafilm-sealed petri dishes stored in airtight containers with desiccant packets can suffice, provided regular monitoring and subculturing are maintained.

In conclusion, maintaining agar cultures long-term is a blend of science and diligence. By prioritizing sterility, regular subculturing, and stable storage conditions, you can preserve mushroom strains for years. Whether for research, cultivation, or conservation, the key lies in treating these cultures as living archives, demanding respect and care to ensure their survival. With the right approach, even dry mushroom clones can thrive on agar, bridging the gap between preservation and propagation.

Can Mushrooms Thrive Without Oxygen? Exploring Anaerobic Growth Conditions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, agar can be used to clone dry mushrooms by rehydrating the mushroom tissue and transferring it to an agar plate to isolate and grow mycelium.

Rehydrate the dry mushrooms in sterile water, sterilize a small piece of the rehydrated tissue, and then transfer it to a nutrient-rich agar plate to encourage mycelial growth.

Malt Extract Agar (MEA) or Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) are commonly used due to their nutrient content, which supports mycelial growth from mushroom tissue.

Yes, contamination is a risk, especially with dry mushrooms, as they may carry spores or bacteria. Sterile techniques and proper sterilization of equipment are crucial for success.