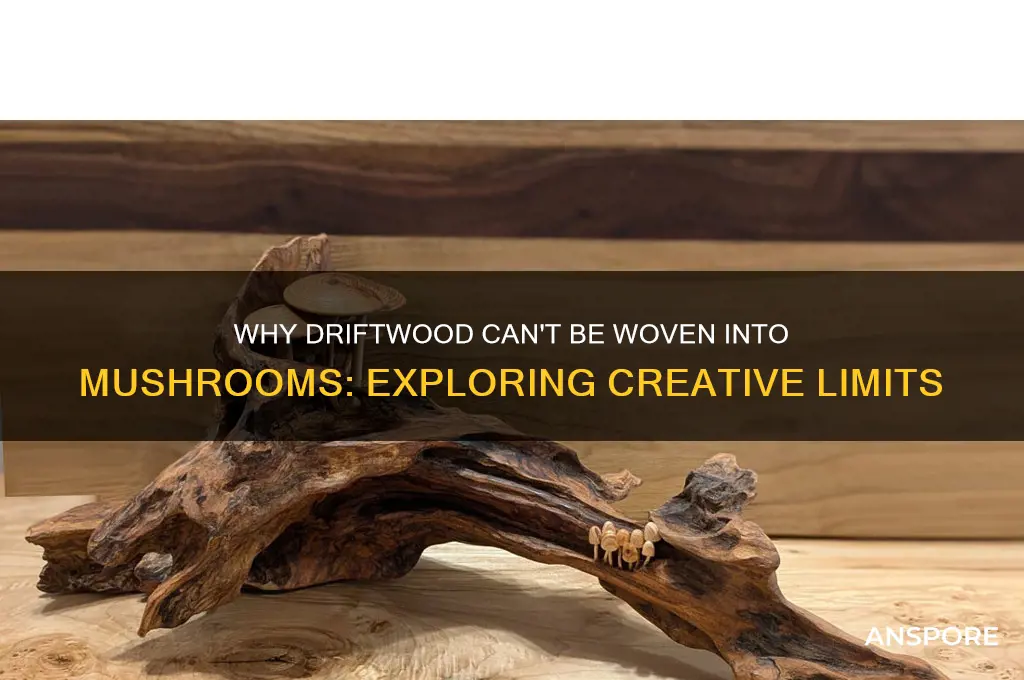

The idea of weaving driftwood into mushrooms may seem intriguing, but it’s fundamentally impossible due to the inherent properties of these materials. Driftwood, weathered by water and time, lacks the flexibility and pliability required for weaving, as its rigid structure resists bending or shaping into intricate forms like mushrooms. Weaving typically involves malleable materials such as fibers, reeds, or vines, which can be interlaced to create patterns and structures. Mushrooms, on the other hand, are organic, delicate, and three-dimensional, making them incompatible with the linear and rigid nature of driftwood. While driftwood can be creatively used in art or sculpture, transforming it into woven mushrooms defies both the material’s capabilities and the principles of weaving itself.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Material | Driftwood |

| Desired Outcome | Mushrooms |

| Feasibility | Not Possible |

| Reason | Driftwood lacks the necessary cellular structure and biological properties to support mushroom growth |

| Alternative Uses for Driftwood | Sculpture, furniture, garden decor, beach-themed crafts |

| Mushroom Cultivation Requirements | Specific substrate (e.g., sawdust, straw, or compost), spores or spawn, controlled environment (temperature, humidity, light) |

| Common Mushroom Substrates | Sawdust, straw, compost, wood chips, grain |

| Driftwood Properties | Hard, brittle, lacks nutrients, and does not retain moisture |

| Mushroom Growth Medium | Requires organic, nutrient-rich, and moisture-retentive material |

| Conclusion | Driftwood is unsuitable for mushroom cultivation due to its physical and chemical properties |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Driftwood's rigidity limits flexibility needed for mushroom shapes

- Mushrooms require organic material, not driftwood's inorganic structure

- Weaving techniques fail on driftwood's uneven, brittle surface

- Mushroom forms demand pliability, absent in driftwood's nature

- Driftwood lacks the texture and softness mushrooms inherently possess

Driftwood's rigidity limits flexibility needed for mushroom shapes

Driftwood, shaped by the relentless forces of water and time, possesses a rigidity that defies the supple curves of mushroom forms. Its natural hardening, a result of prolonged exposure to saltwater and sun, renders it brittle and resistant to bending. Attempting to weave such material into the delicate, organic shapes of mushrooms would likely result in fractures or uneven contours. This physical limitation underscores why driftwood, despite its aesthetic appeal, remains unsuited for crafting mushroom-like structures without significant alteration.

To illustrate, consider the process of weaving: it demands pliability, allowing materials to bend and interlock seamlessly. Willow branches, for instance, are often used in basketry due to their flexibility when soaked. Driftwood, however, lacks this adaptability. Even if soaked or steamed, its cellular structure remains too compromised to retain new shapes without breaking. A practical tip for those experimenting with driftwood is to focus on designs that embrace its linear, angular nature rather than forcing it into forms it cannot sustain.

From a comparative perspective, materials like rattan or vine offer the elasticity needed for intricate, rounded shapes akin to mushrooms. Driftwood’s rigidity places it at the opposite end of this spectrum, making it better suited for static, geometric compositions. For example, a driftwood sculpture might excel as a linear, abstract piece but falter when attempting to mimic the soft, bulbous cap and slender stem of a mushroom. This contrast highlights the importance of material selection in aligning with the desired outcome.

Persuasively, one might argue that driftwood’s limitations are not flaws but opportunities for innovation. Instead of weaving, artisans could explore techniques like carving or assembling pre-cut pieces to achieve mushroom-inspired designs. For instance, a mushroom cap could be carved from a flat piece of driftwood, while the stem could be fashioned from a slender branch. This approach leverages the material’s strength—its durability and textured surface—while bypassing its inflexibility.

In conclusion, driftwood’s rigidity is both a challenge and a characteristic to respect. Its inability to bend into mushroom shapes is not a failure but a reminder of its unique properties. By understanding and working within these constraints, creators can transform what seems like a limitation into a distinctive artistic advantage. Whether through alternative techniques or embracing its natural form, driftwood remains a versatile medium—just not for weaving mushrooms.

Exploring the Unique Scent of Mushroom Wood: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Mushrooms require organic material, not driftwood's inorganic structure

Mushrooms thrive on organic matter, breaking down materials like wood chips, straw, or compost to extract nutrients. Driftwood, however, is inorganic—shaped by water and time into a hardened, mineralized structure devoid of the cellulose and lignin fungi need. Attempting to weave driftwood into mushrooms ignores this fundamental biological requirement, akin to expecting plants to grow in sand without soil. The very essence of mushroom cultivation lies in providing a substrate rich in organic compounds, which driftwood inherently lacks.

Consider the mycelium, the root-like network of fungi, as a microscopic architect. It secretes enzymes to decompose organic material, releasing sugars and nutrients essential for growth. Driftwood’s inorganic nature resists this process, acting more like a barrier than a food source. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) grow vigorously on straw or sawdust but would fail to colonize driftwood due to its mineralized composition. Practical cultivation demands substrates like hardwood sawdust mixed with bran or coffee grounds, not the lifeless remains of water-worn wood.

From a comparative standpoint, organic substrates like straw or cardboard offer a porous, nutrient-rich environment ideal for mycelial expansion. Driftwood, in contrast, is dense and nutrient-poor, its structure hardened by years of submersion. Even if woven into a mushroom-like shape, the absence of organic material renders it biologically inert. This highlights a critical distinction: form without function is futile in nature. Mushrooms are not sculptures but living organisms with specific needs that driftwood cannot fulfill.

For those tempted to experiment, a cautionary note: inorganic materials like driftwood can introduce contaminants or toxins into the growing environment. Mushrooms are bioaccumulators, absorbing substances from their substrate, which could render them unsafe for consumption. Instead, focus on proven organic substrates and follow sterile techniques, such as pasteurizing straw at 160°F (71°C) for 1 hour or using pre-sterilized grain spawn. These methods ensure a clean, nutrient-rich foundation for fungal growth, bypassing the pitfalls of inorganic alternatives.

In conclusion, the idea of weaving driftwood into mushrooms is a poetic metaphor, not a practical endeavor. Mushrooms demand organic material to flourish, a truth rooted in their biology and ecology. By understanding this, cultivators can channel creativity into viable projects, such as crafting mushroom-inspired art from driftwood while reserving organic substrates for actual fungal cultivation. The lesson is clear: respect the science of growth, and let art and biology inspire, not hinder, each other.

Are Mushrooms Harmful? Uncovering Potential Risks and Side Effects

You may want to see also

Weaving techniques fail on driftwood's uneven, brittle surface

Driftwood's allure lies in its weathered texture and organic shapes, but these very qualities render traditional weaving techniques ineffective. Unlike supple willow or rattan, driftwood's surface is a mosaic of cracks, knots, and splintered edges. Standard weaving patterns, which rely on consistent flexibility and pliability, falter against this unpredictable terrain. Each piece of driftwood presents a unique challenge, demanding a departure from conventional methods and a reevaluation of what it means to "weave."

Consider the basic under-over pattern, a cornerstone of many weaving traditions. When applied to driftwood, this technique often results in broken strands or uneven tension. The wood's brittleness resists the gentle bending required for intricate weaves, while its uneven surface creates gaps and snags. Even if a weaver manages to force the material into a semblance of order, the final structure lacks the cohesion and stability of traditional woven forms. This fragility undermines the functional and aesthetic goals of weaving, leaving the creator with a piece that is more fragile than functional.

To illustrate, imagine attempting to weave a mushroom cap from driftwood. The curved shape requires precise manipulation of the material, but driftwood's rigidity makes it impossible to achieve the smooth, continuous lines necessary. Instead of a cohesive cap, the result is a disjointed arrangement of pieces, held together tenuously at best. This example highlights the fundamental incompatibility between driftwood's physical properties and the demands of weaving techniques.

Despite these challenges, some artisans experiment with hybrid approaches, combining weaving with other methods like lashing or gluing. These adaptations acknowledge driftwood's limitations while leveraging its unique beauty. For instance, a mushroom stem might be constructed by bundling small driftwood pieces and securing them with wire, while the cap could be a mosaic of flat shards arranged in a radial pattern. Such techniques prioritize the material's natural characteristics over traditional weaving, resulting in pieces that celebrate driftwood's imperfections rather than fighting against them.

In conclusion, while weaving techniques fail on driftwood's uneven, brittle surface, this failure opens doors to innovative alternatives. By embracing the material's constraints, creators can develop new methods that highlight its inherent beauty. This shift in perspective transforms driftwood from an unsuitable medium for weaving into a canvas for experimental, texture-driven art. The key lies in working with the wood, not against it, allowing its unique qualities to guide the creative process.

Can You Trip Off Cutleaf Mushroom Gummies? Facts and Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mushroom forms demand pliability, absent in driftwood's nature

Driftwood, shaped by water and time, embodies rigidity. Its twisted forms, though captivating, resist bending. Mushrooms, in stark contrast, thrive on supple curves and organic contours. Attempting to weave driftwood into mushroom shapes ignores this fundamental mismatch: one material craves flexibility, the other defies it.

Consider the anatomy of a mushroom. Its cap, often umbrella-like, requires a smooth, rounded surface. The stem, slender and sometimes tapered, demands a seamless transition from base to apex. These forms are born from the give-and-take of living tissue, a pliability driftwood lacks. Even the most skilled artisan would struggle to coax driftwood into these shapes without fracturing its integrity.

This isn’t merely a matter of aesthetics. Driftwood’s brittleness poses practical challenges. Bending it risks splintering, while carving it to mimic mushroom curves would strip away its natural character. Forcing the material into an unnatural form undermines both the beauty of driftwood and the essence of mushrooms.

Instead, embrace driftwood’s inherent qualities. Use its rugged textures and irregular shapes to evoke woodland themes without literal imitation. Pair it with flexible materials like wire or willow for contrast, or incorporate it as a base for mushroom sculptures crafted from clay or papier-mâché. Let driftwood inspire, not dictate, your creation.

Can Mushrooms Grow on a Penis? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Driftwood lacks the texture and softness mushrooms inherently possess

Driftwood, weathered by waves and sun, boasts a rugged, fibrous texture that speaks of its aquatic journey. Its surface, often cracked and splintered, lacks the velvety softness that defines mushrooms. This tactile disparity isn’t merely aesthetic; it’s structural. Mushrooms, composed of chitin and delicate hyphae, offer a pliability that driftwood’s dense, dried wood cannot replicate. Attempting to weave driftwood into mushroom-like forms would result in rigid, unyielding structures, devoid of the organic give that mushrooms naturally possess.

Consider the practical implications of this texture mismatch. Mushrooms, with their soft caps and gills, are designed for spore dispersal and environmental interaction. Driftwood, in contrast, is static and unchanging, its texture resistant to manipulation. For artisans or hobbyists aiming to mimic mushrooms, driftwood’s inflexibility poses a challenge. Soft materials like felt or clay could better capture the mushroom’s essence, while driftwood might serve as a base or accent, not the primary medium.

From a persuasive standpoint, embracing driftwood’s limitations can spark creativity. Instead of forcing it into mushroom-like forms, celebrate its unique qualities. Use driftwood’s rough texture to create contrasting elements in a piece—perhaps a base for a mushroom sculpture made from softer materials. This approach honors both the material’s natural state and the artist’s vision, avoiding the frustration of fighting against its inherent properties.

Comparatively, the softness of mushrooms is tied to their biological function and ephemeral nature. Driftwood, on the other hand, endures, its texture a testament to survival. This contrast highlights why weaving driftwood into mushrooms is not just impractical but philosophically misaligned. Mushrooms symbolize growth and decay, while driftwood represents resilience and permanence. Bridging these two requires more than physical manipulation—it demands a shift in perspective.

For those determined to experiment, start small. Select driftwood pieces with smoother edges and pair them with malleable materials like wire or fabric. Use sandpaper to refine the wood’s texture, but accept that it will never achieve mushroom-like softness. Focus on creating abstract forms that evoke mushrooms rather than literal replicas. This hybrid approach allows driftwood’s strength to complement softer elements, turning limitation into opportunity.

Freezing Dehydrated Mushrooms: A Guide to Preservation and Storage

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, driftwood cannot be woven into mushrooms. Driftwood is a hard, rigid material that lacks the flexibility needed for weaving, and mushrooms are organic structures that cannot be created through weaving techniques.

Driftwood is too brittle and inflexible to be woven, and mushrooms are living organisms that grow naturally rather than being crafted through weaving. The two materials and processes are fundamentally incompatible.

Yes, you can carve or sculpt driftwood into mushroom shapes, but weaving is not a viable method. Other techniques like gluing, stacking, or shaping individual pieces of driftwood can achieve a mushroom-like form.