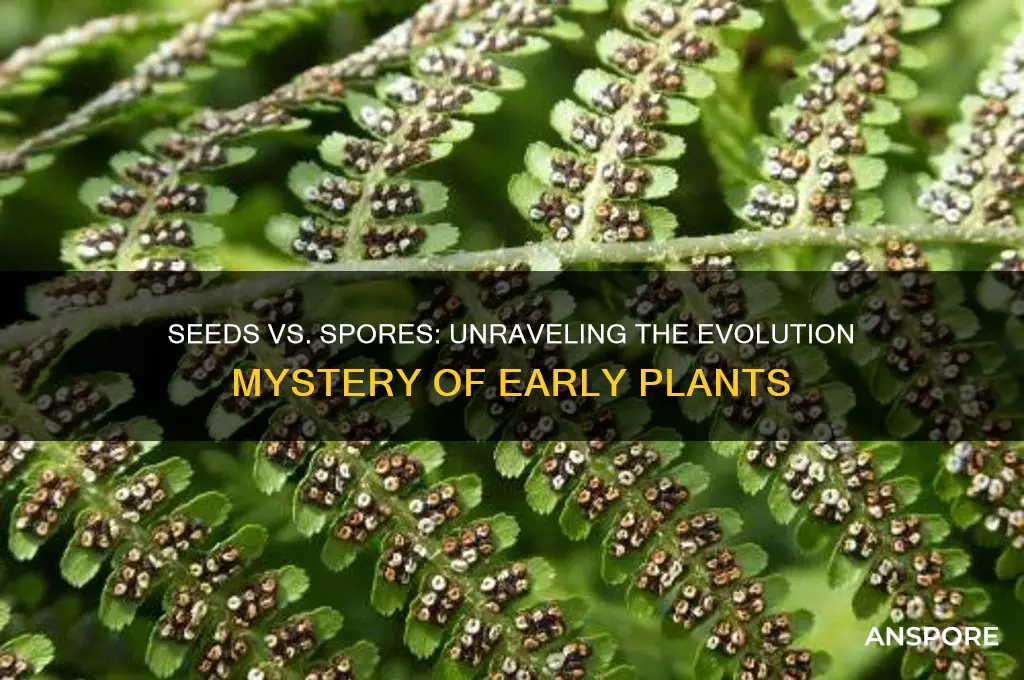

The question of whether seeds or spores evolved first is a fascinating one that delves into the early history of plant life on Earth. Both seeds and spores are reproductive structures, but they represent distinct evolutionary strategies. Spores, characteristic of non-vascular plants like ferns and mosses, are simple, single-celled units that rely on water for dispersal and germination. Seeds, on the other hand, are more complex structures found in vascular plants, such as flowering plants and conifers, and are encased in a protective coat that allows them to survive in drier environments. Fossil evidence and genetic studies suggest that spores evolved first, appearing around 470 million years ago during the Ordovician period, long before the emergence of seeds, which first appeared in the fossil record around 360 million years ago during the Devonian period. This timeline indicates that spores were the earliest form of plant reproduction, paving the way for the later evolution of seeds as plants adapted to life on land.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Which evolved first? | Spores |

| Estimated time of spore evolution | Around 470 million years ago (Ordovician period) |

| Estimated time of seed evolution | Around 360 million years ago (Late Devonian period) |

| Organisms that first developed spores | Early land plants (e.g., bryophytes, lycophytes) |

| Organisms that first developed seeds | Seed ferns (Pteridospermatophyta) and early gymnosperms |

| Function of spores | Asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions |

| Function of seeds | Sexual reproduction, protection of embryo, and nutrient storage |

| Complexity | Spores are simpler structures compared to seeds |

| Dependence on water | Spores require water for fertilization; seeds do not |

| Dispersal mechanisms | Spores are typically dispersed by wind or water; seeds have more diverse dispersal methods (e.g., wind, animals, water) |

| Evolutionary advantage of spores | Allowed early plants to colonize land and survive in diverse environments |

| Evolutionary advantage of seeds | Enhanced survival of offspring, reduced dependence on water, and greater adaptability to terrestrial environments |

| Fossil evidence | Spores are found in older fossil records compared to seeds |

| Current prevalence | Both spores and seeds are widespread, but seeds dominate in modern terrestrial ecosystems |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fossil Evidence: Examines ancient fossils to determine earliest reproductive structures: seeds or spores

- Plant Evolution Timeline: Traces evolutionary history of plants to identify which appeared first

- Reproductive Advantages: Compares survival benefits of seeds versus spores in early environments

- Genetic Studies: Uses DNA analysis to track origins of seed and spore development

- Environmental Factors: Explores how early Earth conditions influenced seed or spore evolution

Fossil Evidence: Examines ancient fossils to determine earliest reproductive structures: seeds or spores

The fossil record holds the key to unraveling the mystery of whether seeds or spores emerged first in the evolutionary timeline. By examining ancient plant fossils, scientists can identify the earliest reproductive structures and piece together the evolutionary history of land plants. This process involves meticulous analysis of fossilized remains, often requiring advanced imaging techniques to reveal intricate details. For instance, the discovery of Cooksonia, a 430-million-year-old fossil, provides critical insights into early land plant reproduction. While Cooksonia lacks true leaves and roots, its sporangia—structures that produce spores—are clearly visible, suggesting that spore-based reproduction predates seed-based systems.

To determine the earliest reproductive structures, paleontologists follow a systematic approach. First, they identify the geological age of the fossil, as older fossils provide clues about earlier evolutionary stages. Next, they analyze the morphology of the reproductive organs, distinguishing between spore-producing sporangia and seed-like structures. For example, fossils of Rhynia, dating back to the Early Devonian (around 407 million years ago), show clear evidence of spore production, reinforcing the idea that spores evolved before seeds. Caution must be exercised, however, as fossilization can distort or obscure delicate structures, making accurate identification challenging.

A comparative analysis of fossil evidence reveals a clear trend: spore-based reproduction appeared significantly earlier than seed-based reproduction. Spores, being simpler and more resilient, likely evolved as an adaptation to the harsh conditions of early land environments. Seeds, on the other hand, represent a more complex innovation, providing protection and nutrients to the developing embryo. The earliest known seed-bearing plants, such as Archaeopteris, emerged during the Late Devonian, approximately 385 million years ago. This timeline suggests a gap of tens of millions of years between the evolution of spores and seeds, highlighting the gradual nature of plant reproductive evolution.

Practical tips for understanding this fossil evidence include exploring digital databases like the Paleobiology Database, which catalog plant fossils and their reproductive structures. Additionally, visiting natural history museums can provide firsthand access to fossil specimens and interpretive displays. For those interested in deeper analysis, learning basic paleobotanical techniques, such as cuticle analysis or coal ball examination, can offer valuable insights into ancient plant life. By engaging with these resources, enthusiasts and researchers alike can contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the origins of plant reproduction.

In conclusion, fossil evidence overwhelmingly supports the hypothesis that spores evolved before seeds. The presence of spore-producing structures in some of the earliest land plant fossils, coupled with the later appearance of seed-like structures, paints a clear evolutionary picture. While the fossil record is incomplete, advancements in technology and continued discoveries will further refine our understanding of this critical transition in plant history. By studying these ancient remains, we not only answer the question of which came first but also gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and resilience of life on Earth.

Exploring Spore: Combining Creepy and Cute Parts for Unique Creations

You may want to see also

Plant Evolution Timeline: Traces evolutionary history of plants to identify which appeared first

The fossil record reveals a clear sequence in plant evolution, and it’s spores, not seeds, that emerged first. Around 470 million years ago, during the Ordovician period, the earliest land plants, such as liverworts and mosses, reproduced via spores. These microscopic, single-celled structures were lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing plants to colonize barren landscapes. Spores were the first adaptation enabling plants to survive and reproduce on land, long before seeds evolved. This early innovation laid the foundation for all subsequent plant life.

To understand why spores preceded seeds, consider the environmental challenges of early terrestrial ecosystems. The first land plants lacked roots, stems, and leaves, relying on moisture for reproduction. Spores, with their simple structure and ability to withstand desiccation, were perfectly suited to this harsh environment. Seeds, on the other hand, are more complex structures that require pollination, fertilization, and protection for the developing embryo—features that evolved much later. By tracing the plant evolution timeline, it becomes evident that spores were the initial solution to the problem of reproduction in a dry, unpredictable environment.

A comparative analysis highlights the evolutionary leap from spores to seeds. While spores are haploid and develop into gametophytes, seeds are the product of a more advanced reproductive strategy. Seeds enclose an embryo, stored nutrients, and a protective coat, ensuring the survival of the next generation even in adverse conditions. This complexity didn’t appear until the Devonian period, around 360 million years ago, with the emergence of seed ferns and early gymnosperms. Seeds represented a significant evolutionary advancement, but they built upon the foundation established by spores millions of years earlier.

For those interested in practical applications, understanding this timeline offers insights into modern plant biology. Spores remain the reproductive method for ferns, fungi, and some algae, while seeds dominate flowering plants and conifers. Gardeners, for instance, can use this knowledge to propagate plants effectively: ferns are best grown from spores, while vegetables and flowers are cultivated from seeds. By recognizing the evolutionary history of these structures, we can better appreciate the diversity of plant life and apply this knowledge to horticulture, conservation, and even agriculture.

In conclusion, the plant evolution timeline unequivocally shows that spores evolved first, predating seeds by over 100 million years. This sequence underscores the gradual complexity of plant reproduction, from simple spore dispersal to the sophisticated mechanisms of seed development. By studying this history, we gain not only a deeper understanding of plant biology but also practical tools for working with plants in various contexts. Spores were the pioneers, seeds the innovators—both shaping the green world we inhabit today.

Understanding Spores: Biology's Tiny Survival Masters Explained Simply

You may want to see also

Reproductive Advantages: Compares survival benefits of seeds versus spores in early environments

Seeds and spores represent two distinct reproductive strategies that emerged early in Earth's history, each with unique advantages tailored to their environments. Spores, produced by plants like ferns and fungi, are lightweight, resilient, and capable of dispersing over vast distances via wind or water. This adaptability allowed early spore-bearing organisms to colonize diverse habitats, from arid deserts to dense forests, with minimal energy investment. However, spores rely on moisture for germination, limiting their success in dry or unpredictable climates. Seeds, on the other hand, evolved later in plant lineages like gymnosperms and angiosperms, offering a protective coat and nutrient reserves that enhance survival in harsh conditions. This comparison highlights how reproductive strategies were shaped by the challenges of early environments.

Consider the survival benefits of seeds in nutrient-poor soils. Unlike spores, seeds contain endosperm or cotyledons, providing embryos with essential nutrients during germination. This internal resource allows seed-bearing plants to thrive in environments where external nutrients are scarce, giving them a competitive edge over spore-dependent species. For example, conifer seeds can germinate in rocky, nutrient-deficient soils, while fern spores require rich, moist substrates to develop. This advantage explains why seed plants dominate modern ecosystems, particularly in challenging terrains.

Spores, however, excel in rapid colonization and resilience. Their small size and hard outer walls enable them to survive extreme conditions, including heat, cold, and desiccation. For instance, fungal spores can remain dormant for decades, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This longevity and durability make spores ideal for environments prone to sudden changes, such as volcanic regions or floodplains. In contrast, seeds, while more resource-intensive to produce, are less suited to such unpredictable settings due to their shorter viability periods and higher energy costs.

The trade-off between seeds and spores also lies in their dispersal mechanisms. Spores’ lightweight nature allows them to travel far and wide, increasing the chances of finding suitable habitats. Seeds, however, often rely on animals or water for dispersal, which limits their range but ensures targeted placement in favorable environments. This difference underscores how spores prioritized quantity and reach, while seeds focused on quality and precision, reflecting their respective evolutionary pressures.

In early environments, the choice between seeds and spores hinged on balancing energy investment and survival probability. Spores offered a low-cost, high-volume strategy suited to unstable, resource-rich habitats, while seeds provided a high-investment, high-reward approach for stable but challenging environments. This dichotomy illustrates how reproductive advantages were finely tuned to the demands of ancient ecosystems, shaping the evolutionary trajectories of plants and fungi alike. Understanding these trade-offs provides insights into the resilience and diversity of life on Earth.

Nematodes and Milky Spore: Unraveling Their Relationship in Soil Health

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Studies: Uses DNA analysis to track origins of seed and spore development

DNA analysis has revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary timelines, particularly in the debate over whether seeds or spores evolved first. By comparing the genetic blueprints of modern plants, scientists can trace back mutations and shared ancestral traits to pinpoint when these reproductive structures diverged. For instance, the presence of homologous genes in both seed-bearing plants (spermatophytes) and spore-bearing plants (like ferns and mosses) suggests a common ancestor. However, the complexity of seed development, involving multiple gene regulatory networks, indicates a later evolutionary refinement compared to the simpler spore mechanism.

To conduct such studies, researchers often focus on conserved genes like *LEAFY* and *FLOWERING LOCUS T*, which play critical roles in plant reproduction. By sequencing these genes across diverse species, scientists can construct phylogenetic trees that reveal evolutionary relationships. For example, a 2018 study published in *Nature Plants* used whole-genome sequencing of early land plants to show that spore-like structures likely predated seeds by millions of years. This approach not only clarifies the timeline but also highlights the incremental genetic changes that led to the seed’s emergence as a more efficient reproductive strategy.

Practical tips for interpreting genetic data in this field include focusing on synonymous mutations, which accumulate neutrally over time and serve as reliable molecular clocks. Additionally, comparing gene expression patterns in developing seeds versus spores can shed light on the evolutionary pressures that drove their divergence. For instance, seeds exhibit higher expression of genes related to desiccation tolerance and nutrient storage, adaptations absent in spores. These insights underscore the seed’s role as a key innovation in plant evolution, enabling survival in drier, more variable environments.

A cautionary note: genetic studies are not without limitations. Horizontal gene transfer, convergent evolution, and incomplete fossil records can complicate interpretations. For example, some algae produce seed-like structures despite being evolutionarily distant from land plants, a case of convergent evolution rather than shared ancestry. To mitigate these challenges, researchers often cross-validate genetic data with paleontological evidence, such as the earliest known seed fossils dating back to the Devonian period (400 million years ago). This multidisciplinary approach ensures a more robust understanding of seed and spore origins.

In conclusion, genetic studies provide a powerful lens for tracking the origins of seed and spore development. By analyzing DNA sequences, gene expression patterns, and evolutionary markers, scientists can reconstruct the stepwise genetic changes that led to these reproductive strategies. While challenges remain, the integration of genetic data with other lines of evidence offers a clearer picture of plant evolution, supporting the hypothesis that spores evolved first, with seeds emerging later as a more complex adaptation to changing environments.

Exploring Fungal Reproduction: Can Spores Be Produced Sexually?

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Explores how early Earth conditions influenced seed or spore evolution

The early Earth was a crucible of extremes, with conditions vastly different from today's relatively stable environment. High levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, intense ultraviolet radiation, and frequent volcanic activity created a challenging landscape for life. These factors played a pivotal role in shaping the evolution of reproductive strategies, particularly the development of seeds and spores. Understanding how these environmental pressures influenced the emergence of seeds and spores provides insight into the resilience and adaptability of early plant life.

Consider the protective mechanisms required to survive such harsh conditions. Spores, with their hardy, desiccation-resistant structures, were well-suited to endure the unpredictable climate of the early Earth. They could remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate. This adaptability allowed spore-producing plants, like ferns and bryophytes, to thrive in environments where water availability was inconsistent. For instance, fossil records show that spore-bearing plants dominated the Devonian period, a time when Earth's climate was characterized by fluctuating humidity and temperature.

In contrast, seeds evolved as a more sophisticated reproductive strategy, offering greater protection and nutrient storage for the developing embryo. Seeds are encased in a protective coat and often contain stored food reserves, enabling them to survive longer periods of adversity. However, this complexity required more stable environmental conditions to develop. The evolution of seeds is closely linked to the colonization of land by plants, particularly during the Carboniferous period, when atmospheric oxygen levels rose, and more predictable rainfall patterns emerged. This stability allowed seed-bearing plants, such as gymnosperms, to outcompete spore-bearing species in certain ecosystems.

A comparative analysis reveals that spores and seeds represent different evolutionary responses to environmental challenges. Spores were the earliest adaptation, thriving in the volatile conditions of the early Earth. Seeds, on the other hand, evolved later as a refinement of reproductive strategies, capitalizing on the stabilizing climate to offer greater advantages in resource allocation and survival. This progression highlights how environmental factors acted as both a constraint and a catalyst for evolutionary innovation.

Practical takeaways from this exploration include the importance of understanding environmental context in evolutionary biology. For educators and researchers, emphasizing the role of early Earth conditions in plant evolution can provide a more nuanced understanding of biodiversity. For gardeners or ecologists, recognizing the resilience of spore-based plants in arid or unpredictable climates can inform conservation strategies. By studying these ancient adaptations, we gain valuable insights into how modern plants might respond to current environmental changes, such as climate variability and habitat disruption.

Anthrax Spores: Can They Lie Dormant for Centuries?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores evolved first, appearing in the fossil record around 470 million years ago during the Ordovician period, long before seeds.

Spores are single-celled reproductive units produced by plants like ferns and fungi, while seeds are multicellular structures containing an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat, found in flowering plants and gymnosperms.

Spores evolved earlier because they are simpler structures that allowed early plants to reproduce and disperse in aquatic or moist environments, which were dominant on Earth before the colonization of land.

Seeds first appeared around 360 million years ago during the Late Devonian period, marking a significant evolutionary advancement in plant reproduction.

Seeds provided advantages such as protection for the embryo, stored nutrients for early growth, and the ability to survive in drier environments, enabling plants to colonize more diverse terrestrial habitats.