The question of whether all gilled mushrooms belong to a single lineage has intrigued mycologists for decades, as it challenges our understanding of fungal evolution and diversity. Gilled mushrooms, characterized by their distinctive lamellar structure, are widespread and ecologically significant, yet their phylogenetic relationships remain complex. Recent advancements in molecular phylogenetics have revealed that gilled mushrooms are not monophyletic, meaning they do not share a single common ancestor exclusive to their group. Instead, they are distributed across multiple lineages within the Basidiomycota division, with some belonging to the Agaricomycetes class while others are found in unrelated groups. This polyphyletic nature suggests that the gilled morphology evolved independently multiple times, driven by convergent evolutionary pressures. Understanding this diversity not only sheds light on fungal evolution but also highlights the remarkable adaptability of mushrooms in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lineage Origin | Not all gilled mushrooms come from a single lineage. Gilled mushrooms (Agaricomycetes) are part of the Basidiomycota division, but they have evolved independently multiple times, indicating polyphyletic origins. |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Gilled mushrooms belong to various orders within Agaricomycetes, such as Agaricales, Boletales, and Russulales, each with distinct evolutionary histories. |

| Morphological Convergence | Gills (lamellae) are a convergent trait, meaning they evolved separately in different lineages as an adaptation for spore dispersal. |

| Genetic Evidence | Molecular studies (e.g., rDNA sequencing) confirm that gilled mushrooms are not monophyletic, with gills arising independently in different fungal groups. |

| Ecological Roles | Despite shared gill structures, these mushrooms occupy diverse ecological niches, from saprotrophic to mycorrhizal associations. |

| Taxonomic Classification | Classification is based on genetic data, not solely on gill presence, reflecting their complex evolutionary relationships. |

| Examples of Polyphyly | Orders like Agaricales (e.g., Agaricus) and Boletales (e.g., Boletus) are not closely related despite both having gilled or pore-like structures. |

Explore related products

$20.94 $29.99

What You'll Learn

Phylogenetic Analysis of Gilled Mushrooms

The phylogenetic analysis reveals that gilled mushrooms belong to several distinct clades within the Agaricomycetes class. For instance, the Agaricales order, which includes well-known genera like *Agaricus* (button mushrooms) and *Coprinus* (inky caps), represents one major lineage. However, other gilled mushrooms, such as those in the orders Russulales (e.g., *Russula* and *Lactarius*) and Boletales (e.g., *Boletus*), are phylogenetically distant from Agaricales. These findings highlight the convergent evolution of gills as a fruiting body structure, which has independently arisen in different lineages to adapt to spore dispersal strategies. Such convergence complicates morphological taxonomy and underscores the importance of molecular data in resolving evolutionary relationships.

To conduct a robust phylogenetic analysis of gilled mushrooms, researchers employ multi-gene approaches, combining data from nuclear, mitochondrial, and protein-coding genes. This increases the resolution and reliability of phylogenetic trees, allowing for a more accurate reconstruction of evolutionary history. Phylogenetic trees constructed from these datasets consistently show that gill formation is not a synapomorphy (shared derived trait) for all gilled mushrooms but rather a homoplasy (trait that evolved independently). For example, the presence of gills in Agaricales and Russulales is not due to common ancestry but rather to separate evolutionary events. This polyphyletic nature of gilled mushrooms has significant implications for fungal systematics, necessitating revisions to taxonomic groupings based on molecular evidence.

Comparative genomics has further enriched our understanding of the evolutionary divergence among gilled mushrooms. Genome-wide analyses have identified key genetic differences and similarities between lineages, shedding light on the molecular mechanisms driving gill development and other morphological traits. For instance, genes involved in fruiting body formation and spore production show divergent patterns across different gilled mushroom groups, supporting the hypothesis of independent evolutionary origins. Additionally, ecological and environmental factors, such as substrate preference and symbiotic relationships, have influenced the diversification of these lineages, contributing to their distinct phylogenetic placements.

In conclusion, phylogenetic analysis unequivocally demonstrates that gilled mushrooms do not originate from a single lineage but are instead scattered across multiple evolutionary branches within the Basidiomycota. This polyphyly is a testament to the complexity of fungal evolution and the limitations of morphology-based taxonomy. As molecular techniques continue to advance, further refinements in the phylogenetic understanding of gilled mushrooms are expected, potentially revealing new lineages and clarifying existing relationships. Such research not only enhances our knowledge of fungal diversity but also has practical applications in fields like mycology, ecology, and biotechnology.

Baking Zucchini and Mushrooms: A Tasty, Healthy Treat

You may want to see also

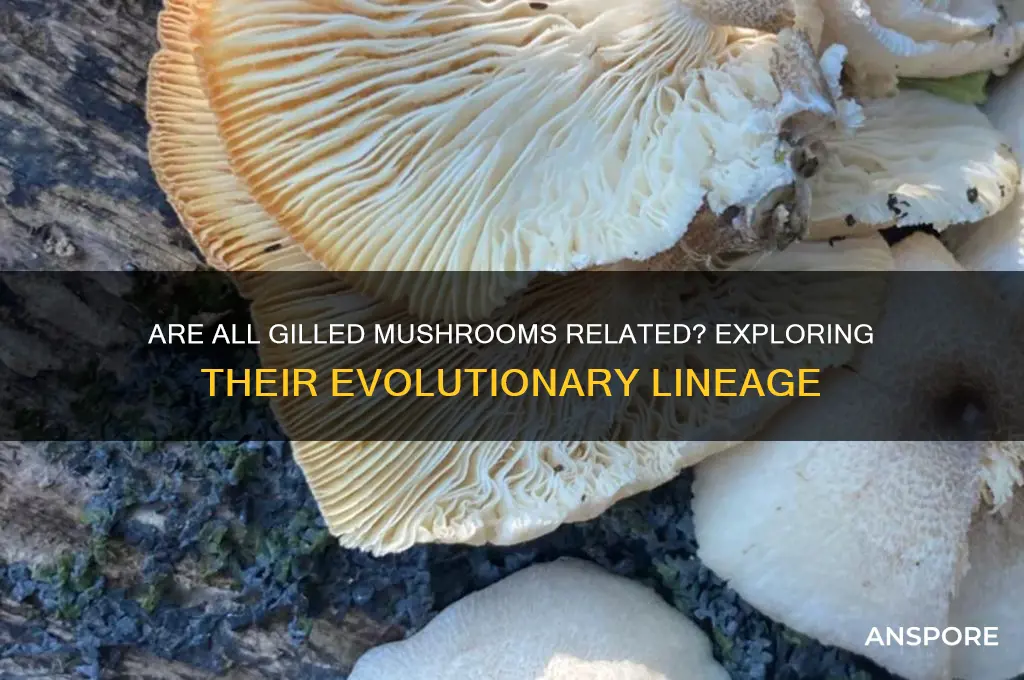

Evolutionary Origins of Lamellae Structures

The presence of lamellae, or gills, in mushrooms is a distinctive feature that has intrigued mycologists and evolutionary biologists alike. Lamellae are the radiating, blade-like structures found on the underside of the mushroom cap, serving as the primary site for spore production and dispersal. Understanding the evolutionary origins of these structures is crucial to addressing the question of whether all gilled mushrooms share a common lineage. Recent research suggests that lamellae have evolved independently multiple times across different fungal lineages, challenging the notion of a single ancestral origin. This phenomenon, known as convergent evolution, indicates that the gill structure provides significant adaptive advantages, such as increased surface area for spore production, which has been selected for in diverse fungal groups.

Molecular phylogenetics has played a pivotal role in unraveling the evolutionary history of gilled mushrooms. Studies based on DNA sequencing have revealed that lamellae-bearing mushrooms are distributed across several major fungal clades, including the Agaricomycetes, a large class within the Basidiomycota division. However, not all Agaricomycetes possess gills, and gilled species are interspersed among non-gilled relatives, suggesting that lamellae have arisen multiple times within this group. For instance, the Agaricales order, which includes well-known gilled mushrooms like *Agaricus* (button mushrooms) and *Coprinus* (inky caps), is nested within a broader phylogenetic tree that also contains poroid and resupinate (crust-like) fungi. This distribution pattern strongly implies that the gill structure has evolved independently in different lineages rather than being inherited from a single common ancestor.

The developmental biology of lamellae further supports the idea of multiple evolutionary origins. The formation of gills involves complex genetic and environmental interactions, with key regulatory genes likely co-opted from ancestral developmental pathways. Comparative studies have identified homologous genes involved in gill development across distantly related gilled mushrooms, but these genes often have different functions in non-gilled fungi. This suggests that the genetic toolkit for gill formation has been assembled and repurposed independently in different lineages, a process known as developmental system drift. Such findings underscore the flexibility and modularity of fungal developmental programs, enabling the recurrent evolution of similar structures under varying selective pressures.

Environmental factors have also likely influenced the convergent evolution of lamellae. Gills are particularly effective in humid environments, where they facilitate efficient spore dispersal while minimizing water loss. This adaptive advantage may have driven the independent evolution of gills in fungi inhabiting similar ecological niches. For example, gilled mushrooms are predominantly found in woodland and forest ecosystems, where the combination of shade and moisture creates ideal conditions for gill function. In contrast, non-gilled fungi often occupy drier or more exposed habitats, where alternative spore-bearing structures, such as pores or teeth, may be more advantageous.

In conclusion, the evolutionary origins of lamellae structures in mushrooms are characterized by convergent evolution rather than a single lineage. Phylogenetic, developmental, and ecological evidence collectively demonstrates that gills have arisen independently multiple times across the fungal tree of life. This highlights the remarkable adaptability of fungi and the role of natural selection in shaping convergent traits. While gilled mushrooms share a common function in spore dispersal, their evolutionary histories are diverse and complex, reflecting the dynamic interplay between genetics, development, and environment in fungal evolution.

Best Temperature to Sauté Mushrooms Perfectly

You may want to see also

Diversity in Agaricomycetes Lineage

The Agaricomycetes, a diverse class within the Basidiomycota division, encompasses a vast array of mushroom-forming fungi, including the majority of gilled mushrooms. These fungi are characterized by their fruiting bodies, which produce spores on gills, pores, or teeth. The question of whether all gilled mushrooms originate from a single lineage has been a subject of extensive research, and the answer lies in understanding the evolutionary diversity within the Agaricomycetes. Phylogenetic studies have revealed that while many gilled mushrooms share a common ancestor, the Agaricomycetes lineage is far from monolithic, exhibiting remarkable diversity in morphology, ecology, and genetic composition.

One of the key findings in the study of Agaricomycetes diversity is the presence of multiple independent origins of gilled mushrooms. Molecular phylogenetics has shown that gilled mushrooms (Agaricales) are not a single, tightly knit group but rather a polyphyletic assemblage, meaning they have evolved the gilled morphology multiple times within the Agaricomycetes. This challenges the traditional view that all gilled mushrooms are closely related and instead highlights the convergent evolution of this trait. For example, the Agaricales order, which includes well-known genera like *Agaricus* (button mushrooms) and *Coprinus* (inky caps), is just one of several lineages within Agaricomycetes that have independently developed gills. Other orders, such as the Boletales (pored mushrooms) and Russulales (toothed mushrooms), have also evolved distinct fruiting body structures, further underscoring the diversity within this class.

The ecological roles of Agaricomycetes contribute significantly to their diversity. These fungi are primarily saprotrophic, decomposing wood and plant material, but they also include mycorrhizal species that form symbiotic relationships with plants. This ecological versatility has driven speciation and adaptation to various habitats, from tropical rainforests to boreal forests. For instance, the genus *Amanita* includes both mycorrhizal species associated with trees and saprotrophic species that decompose organic matter. Such ecological diversity is mirrored in their genetic diversity, with recent genomic studies revealing extensive variation in gene content and regulatory mechanisms across the Agaricomycetes.

Morphological diversity within the Agaricomycetes is equally striking. Beyond the gilled mushrooms, this lineage includes fungi with poroid hymenophores (e.g., *Boletus*), toothed hymenophores (e.g., *Hericium*), and even resupinate (crust-like) forms. This variety in fruiting body structure is accompanied by differences in spore dispersal mechanisms, life cycle strategies, and biochemical capabilities. For example, some Agaricomycetes produce complex secondary metabolites, such as antibiotics and toxins, which play roles in defense, competition, and symbiosis. The ability to produce such compounds varies widely across the lineage, reflecting both evolutionary history and ecological pressures.

In conclusion, the Agaricomycetes lineage exemplifies the extraordinary diversity of mushroom-forming fungi. While many gilled mushrooms share a common ancestry, the broader class is characterized by multiple independent evolutionary trajectories, ecological niches, and morphological adaptations. This diversity is a testament to the dynamic evolutionary processes that have shaped the Agaricomycetes, making them a fascinating subject for both mycological and evolutionary research. Understanding this diversity not only sheds light on the origins of gilled mushrooms but also highlights the complexity and richness of fungal life on Earth.

Goomas and Mushrooms: What's the Real Deal?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Convergent Evolution in Gill Formation

The question of whether all gilled mushrooms share a common lineage has intrigued mycologists for decades. While it might seem intuitive to assume that such a distinctive feature as gills would arise from a single evolutionary origin, research suggests a more complex scenario. Recent phylogenetic studies have revealed that gilled mushrooms, despite their morphological similarities, do not all descend from a single ancestor. Instead, gill formation is a striking example of convergent evolution, where unrelated species independently develop similar traits in response to comparable environmental pressures or functional needs.

Molecular evidence further supports the convergent nature of gill evolution. Genetic analyses have identified distinct developmental pathways for gill formation across different fungal groups. For example, the genes responsible for gill development in Agaricales differ from those in Gilled Polypores, even though the end result—gills—is morphologically similar. This divergence in genetic mechanisms underscores the independent origins of gills in these lineages. Such findings highlight how natural selection can drive the emergence of analogous structures through entirely different evolutionary routes.

The ecological contexts in which gilled mushrooms thrive also shed light on the forces driving convergent evolution. Gills are particularly advantageous in environments where efficient spore dispersal is critical, such as forest floors or decaying wood. Unrelated fungal species occupying these niches have thus evolved gills as a solution to the shared challenge of maximizing reproductive success. This parallelism in adaptation demonstrates how environmental factors can shape convergent traits across diverse lineages, even in the absence of a common ancestor.

In conclusion, the formation of gills in mushrooms is a prime example of convergent evolution, illustrating how similar structures can arise independently in response to comparable selective pressures. While gilled mushrooms may appear morphologically uniform, their evolutionary histories are far more diverse. Understanding this phenomenon not only enriches our knowledge of fungal evolution but also underscores the remarkable ways in which nature finds repeated solutions to common problems. Convergent evolution in gill formation serves as a testament to the ingenuity of natural selection, revealing the intricate interplay between form, function, and environment in the fungal kingdom.

Mushroom Street Drug: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Genetic Markers for Gill Development

The question of whether all gilled mushrooms share a common ancestry is a fascinating one, and it has prompted researchers to delve into the genetic basis of gill development. While not all gilled mushrooms belong to a single lineage, understanding the genetic markers associated with gill formation can provide insights into the evolutionary relationships and developmental pathways across different mushroom species. Genetic markers for gill development are crucial for identifying the genes and regulatory networks that control this complex morphological trait.

One of the key approaches to identifying genetic markers for gill development involves comparative genomics. By comparing the genomes of gilled mushrooms from different lineages, researchers can pinpoint conserved genes and regulatory elements that are consistently associated with gill formation. For example, genes involved in cell differentiation, tissue patterning, and osmotic regulation are often found to play critical roles in gill development. These genes can serve as markers to trace the evolutionary history of gilled mushrooms and determine whether they share a common developmental program.

Molecular studies have highlighted specific gene families that are essential for gill development. For instance, the *Hydra* gene family, known for its role in tissue patterning, has been implicated in the development of gills in Agaricales, one of the largest orders of gilled mushrooms. Similarly, genes involved in the MAPK signaling pathway have been shown to regulate gill morphogenesis in species like *Coprinopsis cinerea*. Identifying such gene families and their regulatory interactions provides a foundation for understanding the genetic basis of gill development across diverse mushroom lineages.

Phylogenetic analyses combined with gene expression studies have further revealed that while gilled mushrooms do not all come from a single lineage, certain developmental pathways are conserved across different groups. For example, the expression patterns of transcription factors like *Brn-1* and *Brn-2* are highly conserved in gilled mushrooms, suggesting that these genes are part of an ancient developmental toolkit. However, variations in downstream targets and regulatory mechanisms indicate that gill development has been fine-tuned independently in different lineages, leading to the diversity of gill structures observed today.

To systematically identify genetic markers for gill development, researchers employ techniques such as RNA sequencing, CRISPR-based gene editing, and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping. These methods allow for the precise identification of genes and mutations that contribute to gill formation. For instance, QTL mapping in hybrid mushroom populations has identified specific genomic regions associated with gill density and arrangement, providing candidate genes for further functional analysis. Such studies not only advance our understanding of gill development but also have practical applications in mushroom breeding and biotechnology.

In conclusion, while gilled mushrooms do not all come from a single lineage, the study of genetic markers for gill development offers a powerful lens to explore their evolutionary relationships and developmental mechanisms. By identifying conserved genes, regulatory networks, and developmental pathways, researchers can unravel the complex history of gill evolution and gain insights into the genetic basis of fungal morphology. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of fungal biology but also opens new avenues for applied research in agriculture, medicine, and ecology.

Mushrooms: Low-Calorie Superfood?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, gilled mushrooms (Agaricales) do not all come from a single lineage. While many gilled mushrooms belong to the order Agaricales, others with similar gill structures have evolved independently in different fungal lineages, such as the orders Russulales and Boletales.

No, gilled mushrooms are not the only fungi with gills. Some fungi outside the Agaricales order, such as certain species in the Russulales and Boletales orders, also have gill-like structures, though they are not true gills in the same anatomical sense.

Gills in mushrooms evolved independently multiple times through convergent evolution. This means different fungal lineages developed gill structures separately to enhance spore dispersal, rather than inheriting the trait from a common ancestor.

Yes, gilled mushrooms or similar structures can be found in non-Agaricales lineages. For example, some species in the Russulales order have structures resembling gills, though they are technically folded or forked, not true gills.

Agaricales gilled mushrooms are distinguished by their true gills (lamellae) attached to a central stipe, their spore-producing basidia, and their shared evolutionary history. Non-Agaricales gilled fungi may have similar structures but differ in anatomy, spore dispersal mechanisms, or genetic lineage.