Blastocladiomycota, a diverse phylum of fungi, is known for its unique characteristics, particularly in its reproductive structures. One of the most intriguing features of this group is the presence of flagellated spores, which sets them apart from most other fungi. These flagellated spores, also known as zoospores, are capable of swimming through aqueous environments, allowing Blastocladiomycota to disperse and colonize new habitats effectively. This adaptation is a key factor in their ecological success, especially in moist and aquatic ecosystems. The flagellated nature of their spores not only highlights their evolutionary distinctiveness but also underscores their importance in understanding fungal diversity and adaptation.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Blastocladiomycota spore types: Identifying whether flagellated spores are present in Blastocladiomycota life cycles

- Flagellated spore function: Role of flagella in Blastocladiomycota spore motility and dispersal

- Comparative fungal spores: Contrasting Blastocladiomycota spores with other fungal groups' spore structures

- Blastocladiomycota reproduction: How flagellated spores contribute to Blastocladiomycota reproductive strategies

- Evolutionary significance: Flagellated spores' role in Blastocladiomycota's evolutionary adaptation and survival

Blastocladiomycota spore types: Identifying whether flagellated spores are present in Blastocladiomycota life cycles

Blastocladiomycota, a diverse group of fungi, exhibit a unique range of spore types that play critical roles in their life cycles. Among these, flagellated spores, known as zoospores, are a defining feature of this phylum. These motile spores are equipped with one or more flagella, enabling them to swim through aqueous environments in search of suitable substrates for growth. This characteristic distinguishes Blastocladiomycota from other fungal groups, which typically produce non-motile spores. Understanding the presence and function of flagellated spores is essential for identifying and classifying species within this phylum.

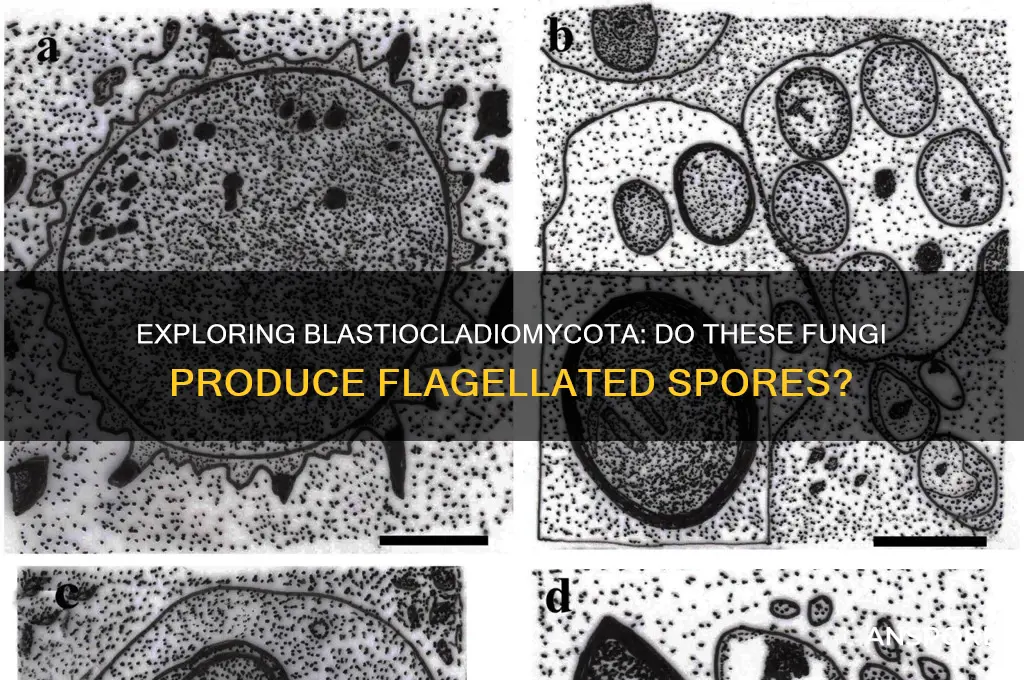

To identify whether flagellated spores are present in the life cycle of a Blastocladiomycota species, researchers employ a combination of microscopic observation and molecular techniques. Microscopically, zoospores can be visualized using phase-contrast or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, which highlights their flagellar movement. A key indicator is the observation of spores with one or two whiplash flagella, often released from sporangia or gametangia in aquatic environments. For example, *Blastocladiella emersonii* produces biflagellate zoospores, while *Allomyces arbusculus* releases uniflagellate spores, demonstrating the variability within the phylum.

Molecular methods, such as PCR amplification of flagellar genes, complement microscopic observations by providing genetic evidence of flagellated spore production. Genes encoding flagellar proteins, such as those in the *FLA* family, are conserved across Blastocladiomycota and can be used as markers. By sequencing these genes, researchers can confirm the presence of flagellated spores even in species where zoospore release is not readily observable. This dual approach ensures accurate identification and classification, particularly in species with complex or cryptic life cycles.

Practical tips for studying Blastocladiomycota spore types include culturing isolates in nutrient-rich media to induce sporulation and using environmental samples from aquatic habitats, where these fungi thrive. For microscopy, staining with fluorophores like calcofluor white can enhance spore visibility. When analyzing molecular data, BLAST searches against fungal databases can help verify the identity of flagellar genes. By integrating these techniques, researchers can confidently determine the presence of flagellated spores and gain deeper insights into the evolutionary and ecological significance of Blastocladiomycota.

In conclusion, identifying flagellated spores in Blastocladiomycota requires a multifaceted approach combining microscopy and molecular biology. The presence of these motile spores is a hallmark of the phylum, reflecting their adaptation to aquatic environments. By mastering the techniques outlined above, researchers can accurately characterize spore types, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of Blastocladiomycota diversity and biology. This knowledge not only aids in taxonomic studies but also highlights the unique ecological roles these fungi play in their habitats.

Can Spores Produce Toxins? Unveiling the Hidden Dangers of Microbial Spores

You may want to see also

Flagellated spore function: Role of flagella in Blastocladiomycota spore motility and dispersal

Blastocladiomycota, a group of fungi closely related to animals, produce flagellated spores known as zoospores. These spores are equipped with one or more flagella, whip-like structures that enable active motility. Unlike passive dispersal mechanisms seen in many fungal spores, flagella allow Blastocladiomycota zoospores to swim through aqueous environments, such as soil or water, in search of suitable substrates for germination. This active motility is a key adaptation for their survival and colonization in diverse habitats.

The function of flagella in Blastocladiomycota spores extends beyond mere movement. Flagella are powered by a complex system of microtubules and dynein arms, which convert chemical energy into mechanical force. This energy-efficient system allows zoospores to navigate toward nutrient gradients, a behavior known as chemotaxis. For example, zoospores of *Blastocladiella emersonii* exhibit positive chemotaxis toward glucose, ensuring they locate and colonize nutrient-rich environments. This targeted dispersal mechanism enhances their ecological success and competitive advantage in natural settings.

From a practical standpoint, understanding flagellated spore function in Blastocladiomycota has implications for biotechnology and agriculture. Zoospores’ motility and chemotactic abilities can be harnessed for targeted delivery of biocontrol agents or biofertilizers. For instance, engineered zoospores could be used to deliver antifungal compounds directly to plant roots, combating soil-borne pathogens. However, caution must be exercised to prevent unintended environmental impacts, as the dispersal efficiency of flagellated spores can lead to rapid colonization of non-target areas.

Comparatively, the flagella of Blastocladiomycota zoospores share structural similarities with those of algae and protozoa but serve distinct ecological roles. While algal flagella primarily aid in photosynthesis and nutrient uptake, those in Blastocladiomycota are specialized for dispersal and substrate localization. This evolutionary divergence highlights the adaptability of flagella across different organisms. By studying these differences, researchers can gain insights into the convergent evolution of motility mechanisms and their functional optimization in specific environments.

In conclusion, the flagella of Blastocladiomycota spores are not just tools for movement but sophisticated systems that enhance survival and dispersal. Their role in chemotaxis, energy efficiency, and targeted colonization underscores their importance in fungal ecology. Leveraging this knowledge can lead to innovative applications in biotechnology, but it also requires careful consideration of ecological consequences. The study of flagellated spores in Blastocladiomycota thus bridges fundamental biology with practical solutions, offering a unique lens into the intersection of motility and adaptation.

Fixing Spore Error 1004: Default Preferences Not Found Solutions

You may want to see also

Comparative fungal spores: Contrasting Blastocladiomycota spores with other fungal groups' spore structures

Blastocladiomycota stand out in the fungal kingdom due to their flagellated spores, a feature that sharply contrasts with the spore structures of other fungal groups. Unlike the majority of fungi, which produce non-motile spores, Blastocladiomycota develop zoospores equipped with one or two flagella, enabling them to swim through aqueous environments. This adaptation is crucial for their aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyles, allowing them to disperse efficiently in water. In contrast, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, the two largest fungal phyla, produce spores that rely on wind, water, or vectors for dispersal, lacking any motility mechanisms. This fundamental difference in spore structure highlights the evolutionary divergence of Blastocladiomycota from other fungi, reflecting their unique ecological niche.

To understand the significance of flagellated spores, consider the spore dispersal strategies of other fungal groups. For instance, Ascomycota, such as *Penicillium* and *Aspergillus*, produce ascospores or conidia that are lightweight and easily carried by air currents. Similarly, Basidiomycota, including mushrooms and rust fungi, release basidiospores from gills or other specialized structures, relying on wind for dispersal. These spores are non-motile and often possess adaptations like hydrophobic surfaces or aerodynamic shapes to enhance passive dispersal. In contrast, the flagellated zoospores of Blastocladiomycota actively seek out new habitats, a trait more commonly associated with protists than fungi. This active dispersal mechanism underscores the evolutionary convergence of Blastocladiomycota with certain protists, despite their fungal classification.

The development of flagellated spores in Blastocladiomycota is a complex process involving specific cellular structures. Zoospores are produced within sporangia and are released into the environment when mature. The flagella, composed of microtubules arranged in the characteristic "9+2" pattern, are powered by dynein arms, enabling propulsive movement. This structural complexity is absent in the spores of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which lack flagella and associated motility machinery. Instead, these fungi invest in producing large quantities of spores to increase the likelihood of successful dispersal. For example, a single mushroom cap can release billions of basidiospores in a single night, a strategy that contrasts sharply with the targeted, energy-intensive approach of Blastocladiomycota zoospores.

From a practical standpoint, the flagellated spores of Blastocladiomycota have implications for their ecological roles and biotechnological applications. Their ability to swim allows them to colonize nutrient-rich environments rapidly, making them important players in nutrient cycling in aquatic ecosystems. Additionally, their motility has been exploited in laboratory settings to study fungal development and cell biology. For researchers, understanding the mechanisms behind flagellated spore production could inspire innovations in biotechnology, such as engineered microbial systems for environmental remediation. In contrast, the non-motile spores of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are more frequently studied for their roles in food production (e.g., yeast in baking and brewing) and medicine (e.g., penicillin production), highlighting the diverse applications of fungal spores across different groups.

In summary, the flagellated spores of Blastocladiomycota represent a unique adaptation that sets them apart from other fungal groups. While Ascomycota and Basidiomycota rely on passive dispersal mechanisms, Blastocladiomycota invest in active motility, reflecting their distinct ecological and evolutionary trajectories. This comparison not only illuminates the diversity of fungal spore structures but also underscores the importance of studying lesser-known fungal groups like Blastocladiomycota. By examining these differences, researchers can gain deeper insights into fungal biology and harness their unique traits for practical applications.

Using Spore Creature Creator Creations for Commercial Projects: Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Blastocladiomycota reproduction: How flagellated spores contribute to Blastocladiomycota reproductive strategies

Blastocladiomycota, a diverse group of fungi, employ a unique reproductive strategy centered around flagellated spores. These spores, known as zoospores, are equipped with one or more flagella, enabling them to swim through aqueous environments. This motility is a critical adaptation for Blastocladiomycota, which often inhabit damp soils, freshwater, and decaying organic matter. Unlike stationary spores, zoospores actively seek out favorable substrates, increasing the chances of successful colonization and resource acquisition. This mobility is particularly advantageous in heterogeneous environments where nutrients are patchily distributed.

The life cycle of Blastocladiomycota involves both asexual and sexual reproduction, with zoospores playing a pivotal role in both phases. During asexual reproduction, zoospores are produced in sporangia and released into the environment. Once they locate a suitable substrate, they encyst, germinate, and develop into new thalli. This process allows for rapid dispersal and colonization of new habitats. In sexual reproduction, zoospores of compatible mating types fuse to form a zygote, which later undergoes meiosis to produce new zoospores. This dual functionality of zoospores—both as agents of dispersal and as gametes—highlights their centrality to Blastocladiomycota reproductive success.

Flagellated spores also confer resilience to Blastocladiomycota in challenging environments. For instance, in habitats prone to desiccation or nutrient scarcity, zoospores can remain dormant in a cyst stage until conditions improve. This dormancy mechanism ensures survival during unfavorable periods while maintaining the potential for rapid proliferation when resources become available. Additionally, the ability to swim allows zoospores to escape predators or adverse conditions, further enhancing their survival and dispersal capabilities.

From a practical standpoint, understanding Blastocladiomycota’s flagellated spores has implications for fields like agriculture and ecology. For example, certain Blastocladiomycota species are known to parasitize algae, which can impact algal blooms in aquatic ecosystems. Managing these interactions requires knowledge of zoospore behavior, such as their chemotactic responses to algal exudates. Similarly, in agricultural settings, Blastocladiomycota can affect plant health, either as pathogens or as biocontrol agents against other fungi. Tailoring strategies to disrupt or enhance zoospore motility could thus be a targeted approach to managing these organisms.

In conclusion, flagellated spores are not merely a reproductive feature of Blastocladiomycota but a cornerstone of their ecological success. Their motility, versatility, and adaptability underpin the fungi’s ability to thrive in diverse environments. By studying these spores, researchers can uncover novel insights into fungal biology and develop practical applications for managing Blastocladiomycota in natural and agricultural systems. This unique reproductive strategy exemplifies the ingenuity of evolutionary adaptations in the microbial world.

Can You Kill Botulism Spores? Effective Methods and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Evolutionary significance: Flagellated spores' role in Blastocladiomycota's evolutionary adaptation and survival

Blastocladiomycota, a group of fungi closely related to animals, possess flagellated spores, a feature that sets them apart from most other fungi. This unique characteristic is not merely a biological curiosity but a key to their evolutionary success. Flagellated spores, or zoospores, enable these organisms to navigate aquatic environments with precision, a capability that has profound implications for their survival and adaptation. By actively swimming, these spores can locate optimal substrates for growth, evade predators, and colonize new habitats, ensuring the species’ persistence in dynamic ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of *Blastocladiella emersonii*, a well-studied species within this group. After germination, the fungus produces zoospores equipped with a single, posterior flagellum. These spores can detect chemical gradients in their environment, a process known as chemotaxis, allowing them to swim toward nutrient-rich areas. For instance, zoospores are attracted to amino acids and simple sugars, which signal the presence of organic matter suitable for colonization. This targeted movement increases their chances of successful germination and reduces energy expenditure compared to passive dispersal methods.

The evolutionary advantage of flagellated spores becomes even more apparent when comparing Blastocladiomycota to non-motile fungi. While the latter rely on wind, water currents, or vectors for spore dispersal, Blastocladiomycota actively seek out favorable conditions. This proactive approach enhances their competitive edge in nutrient-limited environments, such as freshwater ecosystems. Moreover, the ability to swim allows zoospores to escape adverse conditions, such as high salinity or predation, by relocating to safer areas. This adaptability is particularly crucial in fluctuating habitats, where survival often depends on rapid response to environmental changes.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the role of flagellated spores in Blastocladiomycota’s survival has implications for biotechnology and ecology. For example, their chemotactic abilities could inspire the development of bioengineered systems for targeted drug delivery or pollutant remediation. Ecologically, these fungi play a vital role in nutrient cycling, breaking down complex organic matter in aquatic systems. By studying their dispersal mechanisms, scientists can better predict how fungal communities respond to environmental disturbances, such as climate change or habitat fragmentation.

In conclusion, the flagellated spores of Blastocladiomycota are not just a biological trait but a testament to the ingenuity of evolution. Their motility enables these fungi to thrive in challenging environments, ensuring their survival and ecological relevance. As we continue to explore the natural world, the unique adaptations of organisms like Blastocladiomycota remind us of the intricate strategies life employs to persist and flourish.

Is Milky Spore Powder Safe? Potential Risks to Humans Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Blastocladiomycota produce flagellated spores, specifically zoospores, which are a defining characteristic of this fungal phylum.

The flagellated spores in Blastocladiomycota are called zoospores, which are motile and play a key role in their life cycle.

The flagellated spores (zoospores) of Blastocladiomycota move using one or more whip-like flagella, allowing them to swim through water or moist environments.

No, not all spores of Blastocladiomycota are flagellated. While zoospores are flagellated, they also produce non-motile spores like sporangiospores in certain stages of their life cycle.

Blastocladiomycota produce flagellated spores (zoospores) to disperse efficiently in aquatic or moist environments, aiding in colonization and survival in their habitats.