Charophytes, a group of freshwater green algae closely related to land plants, are of significant interest in understanding the evolutionary transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments. One key aspect of this transition is the development of desiccation-resistant spores, which allow organisms to survive in dry conditions. While charophytes exhibit various adaptations to their aquatic habitats, the question of whether they produce desiccation-resistant spores remains a topic of scientific inquiry. Some species of charophytes have been observed to form structures like oospores, which are resilient to harsh conditions, but their specific resistance to desiccation is still under investigation. Understanding this feature could provide crucial insights into the evolutionary mechanisms that enabled early land plants to colonize terrestrial ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Charophytes have desiccation-resistant spores? | Yes |

| Type of spores | Oospores |

| Function of oospores | Survive harsh environmental conditions, including desiccation |

| Wall structure of oospores | Thick and resistant, providing protection against drying out |

| Metabolic activity during desiccation | Reduced, allowing for long-term survival in a dormant state |

| Significance | Allows charophytes to persist in fluctuating aquatic environments, contributing to their success in diverse habitats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Charophyte spore structure and adaptations

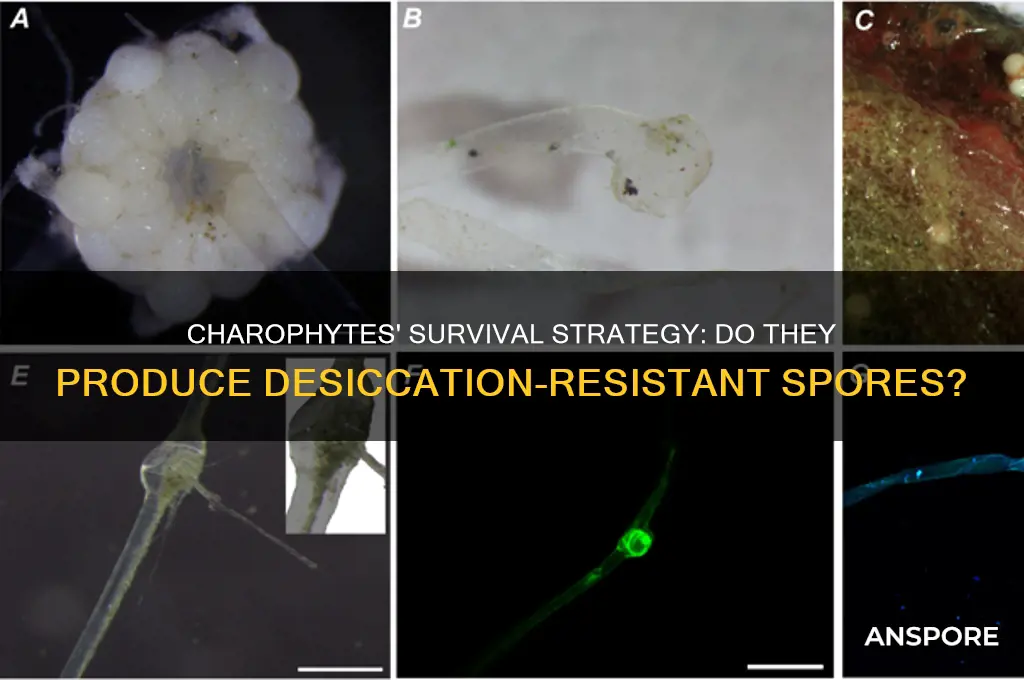

Charophytes, often considered the evolutionary link between aquatic plants and terrestrial flora, exhibit unique spore structures that reflect their adaptation to diverse environments. Their spores are typically encased in a robust, multi-layered wall composed of sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer. This structure provides a critical barrier against desiccation, enabling charophyte spores to survive in both aquatic and transiently dry habitats. Unlike the spores of many land plants, which are often specialized for wind dispersal, charophyte spores are adapted for water-based dispersal, yet retain features that mitigate water loss in fluctuating conditions.

One of the most striking adaptations of charophyte spores is their ability to enter a state of dormancy when exposed to dry conditions. This dormancy is facilitated by the spore’s low metabolic rate and the impermeability of its outer layers, which minimize water loss. For instance, species like *Chara vulgaris* produce oospores that can remain viable in soil or sediment for years, waiting for rehydration to resume growth. This strategy ensures survival in ephemeral water bodies, where desiccation is a recurring threat. Practical applications of this trait are seen in aquaculture, where charophyte spores are used to restore degraded aquatic ecosystems, leveraging their resilience to harsh conditions.

Comparatively, the spore structure of charophytes differs from that of bryophytes and ferns, which rely on thinner walls and rapid germination to avoid desiccation. Charophytes, however, prioritize long-term survival over immediate germination, a trade-off that reflects their transitional evolutionary position. The thickness of their spore walls, often exceeding 1 micrometer, is a key factor in their desiccation resistance, though it also slows their response to favorable conditions. This balance between durability and functionality highlights the adaptive ingenuity of charophytes.

To study charophyte spore adaptations, researchers often employ techniques like scanning electron microscopy to examine wall morphology and permeability assays to measure water retention. For hobbyists or educators, observing charophyte spores under a light microscope can reveal their distinctive structure, while exposing them to controlled drying cycles demonstrates their resilience. A simple experiment involves placing spores in a desiccator for 48 hours and then rehydrating them to observe germination rates, typically around 70-80% for healthy spores.

In conclusion, the spore structure and adaptations of charophytes exemplify a sophisticated response to environmental challenges. Their sporopollenin-rich walls, dormancy mechanisms, and balanced trade-offs between survival and growth underscore their role as evolutionary pioneers. Understanding these features not only sheds light on plant evolution but also offers practical insights for conservation and biotechnology, where desiccation-resistant spores are invaluable assets.

Mastering Mushroom Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Desiccation resistance mechanisms in charophytes

Charophytes, often considered the evolutionary link between aquatic algae and terrestrial plants, exhibit remarkable desiccation resistance mechanisms that enable their survival in fluctuating aquatic environments. Unlike many algae, charophytes produce structures like oospores and zygotes that can withstand prolonged periods of dryness. These spores are encased in robust cell walls composed of sporopollenin, a highly durable biopolymer that acts as a protective barrier against water loss. This structural adaptation is crucial for their persistence in ephemeral water bodies, where desiccation is a frequent threat.

One of the key mechanisms employed by charophytes is the accumulation of compatible solutes, such as sugars and sugar alcohols, within their cells. These compounds act as osmoprotectants, stabilizing cellular structures and maintaining membrane integrity during dehydration. For instance, species like *Chara vulgaris* have been observed to increase their trehalose levels under desiccating conditions, a sugar known for its exceptional water retention properties. This metabolic response not only aids in desiccation tolerance but also facilitates rapid rehydration and recovery once water becomes available again.

Another critical strategy is the regulation of gene expression in response to desiccation stress. Studies have identified genes in charophytes that encode for late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins, which are known to protect cellular components from dehydration damage. These proteins bind to membranes and other macromolecules, preventing their denaturation during drying. Additionally, charophytes activate antioxidant systems to mitigate oxidative stress caused by desiccation, ensuring cellular function is preserved even in the absence of water.

Comparatively, charophytes’ desiccation resistance mechanisms share similarities with those of bryophytes and resurrection plants, yet they are uniquely adapted to their aquatic-terrestrial transitional niche. While bryophytes rely heavily on poikilohydry (tolerating cellular dehydration), charophytes combine this with the production of desiccation-resistant spores, offering a dual survival strategy. This distinction highlights their evolutionary significance as precursors to land plants, which further developed these traits to colonize arid environments.

For researchers and conservationists, understanding these mechanisms provides insights into plant evolution and potential applications in biotechnology. For example, the sporopollenin biosynthesis pathway in charophytes could inspire the development of drought-resistant crops. Practical tips for studying these mechanisms include using controlled desiccation experiments to observe spore viability and employing molecular techniques to track gene expression changes. By focusing on charophytes, we not only unravel their survival secrets but also unlock tools for addressing modern agricultural challenges.

Peziza Spores: Understanding Their Haploid or Diploid Nature Explained

You may want to see also

Comparing charophyte and land plant spores

Charophytes, often considered the closest living relatives of land plants, produce spores that share some similarities with those of their terrestrial counterparts. However, a critical distinction lies in their desiccation resistance. Land plant spores, such as those of ferns and mosses, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme dryness, a trait essential for survival in diverse environments. Charophyte spores, while adapted to aquatic or moist conditions, lack this robust desiccation resistance. This difference highlights a key evolutionary divergence: land plants developed spores capable of enduring harsh, dry conditions, while charophytes remained tied to water-rich habitats.

To understand this disparity, consider the structural adaptations of spores. Land plant spores often have thick, multilayered walls composed of sporopollenin, a highly durable polymer that protects against desiccation. Charophyte spores, in contrast, typically have thinner walls and rely on their aquatic environment for moisture retention. For example, *Chara* species release spores directly into water, where they can germinate without needing to survive prolonged dryness. This reliance on moisture underscores why charophytes never fully transitioned to land, unlike their evolutionary cousins.

From a practical standpoint, this comparison has implications for plant conservation and research. Scientists studying early plant evolution often examine charophytes to understand the transition from water to land. By comparing spore structures, researchers can pinpoint the evolutionary innovations that enabled land colonization. For instance, experiments exposing charophyte and land plant spores to controlled desiccation levels reveal stark differences in survival rates, providing empirical evidence of their distinct adaptations.

Persuasively, this analysis suggests that desiccation resistance was a pivotal trait in the conquest of land. Without it, plants would have remained confined to aquatic environments. Charophytes, despite their evolutionary proximity to land plants, serve as a living reminder of the limitations imposed by a lack of this adaptation. Their spores, while functional in water, fail to bridge the gap to terrestrial life, making them an intriguing case study in evolutionary biology.

In conclusion, comparing charophyte and land plant spores reveals a fundamental difference in desiccation resistance, rooted in their respective environments and evolutionary histories. Land plants’ durable spores enabled their success on dry land, while charophytes’ moisture-dependent spores kept them anchored to water. This comparison not only enriches our understanding of plant evolution but also highlights the critical role of spore adaptations in shaping life on Earth.

Exploring the Potential for Spore Mines to Advance in Modern Warfare

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental triggers for spore formation

Charophytes, often considered the evolutionary link between aquatic plants and terrestrial flora, exhibit a fascinating response to environmental stressors, particularly in spore formation. One of the key triggers for this process is desiccation, a condition where water availability drops to critical levels. When charophytes detect a decline in their aquatic habitat’s moisture, they initiate spore production as a survival mechanism. These spores are not merely dormant cells but are equipped with robust cell walls and protective layers that resist desiccation, ensuring the plant’s genetic material survives until conditions improve. This adaptive strategy highlights the intricate relationship between environmental cues and reproductive responses in charophytes.

To understand the environmental triggers for spore formation, consider the light and temperature fluctuations that charophytes experience in their habitats. Reduced light intensity, often a precursor to drying conditions, signals the plant to allocate resources toward spore development. Similarly, temperature shifts, particularly a rise in warmth followed by cooling, mimic seasonal changes and prompt spore formation. For instance, in laboratory settings, exposing charophytes to 12 hours of light at 25°C followed by a 12-hour dark period at 15°C accelerates spore production. These controlled conditions demonstrate how specific environmental cues can be manipulated to study and potentially enhance spore formation in charophytes.

A comparative analysis of charophytes and their terrestrial descendants reveals that nutrient availability also plays a critical role in triggering spore formation. In nutrient-poor environments, charophytes prioritize energy allocation to reproductive structures over vegetative growth. This is particularly evident in species like *Chara vulgaris*, where phosphorus deficiency has been shown to increase spore production by up to 40%. Such findings underscore the importance of nutrient sensing in the plant’s decision to form spores, a trait that likely contributed to the success of early land plants in colonizing nutrient-scarce environments.

Practical applications of understanding these triggers extend to conservation and biotechnology. For instance, in restoring aquatic ecosystems, monitoring environmental factors like light, temperature, and nutrient levels can predict and manage charophyte spore formation, ensuring their survival during habitat disturbances. Additionally, biotechnologists can harness these triggers to cultivate charophytes for biofuel production, as their desiccation-resistant spores provide a stable source of biomass. By manipulating environmental conditions, researchers can optimize spore yield, making charophytes a viable candidate for sustainable energy solutions.

In conclusion, the environmental triggers for spore formation in charophytes—desiccation, light and temperature changes, and nutrient availability—are not isolated factors but interconnected signals that drive this adaptive response. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on the evolutionary transition from water to land but also offers practical insights for conservation and biotechnology. Whether in a natural habitat or a controlled lab setting, these triggers provide a roadmap for studying and leveraging charophytes’ remarkable resilience.

Do All Bacillus Species Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Role of desiccation resistance in charophyte evolution

Charophytes, often considered the evolutionary link between aquatic algae and terrestrial plants, exhibit a fascinating adaptation: desiccation-resistant spores. These spores, akin to the seeds of early land plants, allowed charophytes to survive in fluctuating aquatic environments, particularly those prone to drying. This trait was not merely a passive survival mechanism but a key innovation that facilitated their persistence in shallow, ephemeral water bodies. By encapsulating their genetic material within a protective, drought-tolerant structure, charophytes could endure harsh conditions, ensuring their lineage’s continuity even when their habitats temporarily vanished.

The evolution of desiccation-resistant spores in charophytes highlights a critical step in the transition from water to land. While charophytes themselves remain aquatic, their spores’ ability to withstand drying mirrors the adaptations seen in the earliest land plants. This suggests that the genetic and physiological mechanisms for desiccation resistance were already present in charophytes, providing a foundation for the colonization of terrestrial environments. For instance, the sporopollenin found in charophyte spores is chemically similar to that in land plant spores and pollen, indicating a shared evolutionary heritage.

From a practical standpoint, understanding desiccation resistance in charophytes offers insights into plant conservation and biotechnology. Scientists studying drought-resistant crops often look to early plant lineages for inspiration. Charophytes, with their robust spores, serve as a model for developing crops that can withstand water scarcity. For example, isolating the genes responsible for sporopollenin synthesis in charophytes could inform genetic engineering efforts to enhance crop resilience. This application underscores the relevance of charophyte biology beyond evolutionary curiosity.

Comparatively, desiccation resistance in charophytes contrasts with other aquatic organisms that rely on migration or rapid reproduction to cope with drying habitats. Charophytes’ strategy of producing durable spores represents a long-term investment in survival, trading immediate reproductive output for long-term persistence. This distinction highlights the diversity of evolutionary strategies in response to environmental stress and underscores the uniqueness of charophytes’ approach.

In conclusion, the role of desiccation resistance in charophyte evolution is a testament to the ingenuity of life in adapting to challenging environments. By developing spores capable of withstanding drying, charophytes not only secured their survival in fluctuating aquatic habitats but also laid the groundwork for the conquest of land. This adaptation, rooted in their biology, continues to inspire scientific inquiry and practical applications, bridging the gap between ancient evolution and modern innovation.

Spore Syringe Shelf Life: Fridge Storage Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some charophytes, particularly those in the genus *Chara*, produce desiccation-resistant spores called oospores, which allow them to survive in drying environments.

Desiccation-resistant spores in charophytes serve as a survival mechanism, enabling them to withstand harsh, dry conditions and disperse to new habitats when water returns.

No, not all charophyte spores are desiccation-resistant. While oospores are highly resistant, other spore types like zoospores are not adapted to survive desiccation.

Charophyte oospores resist desiccation through their thick, protective cell walls and the accumulation of storage compounds like lipids and carbohydrates, which help maintain cellular integrity during drying.

Yes, desiccation-resistant oospores are a key part of the charophyte life cycle, serving as a dormant stage that ensures long-term survival and facilitates colonization of new aquatic environments.