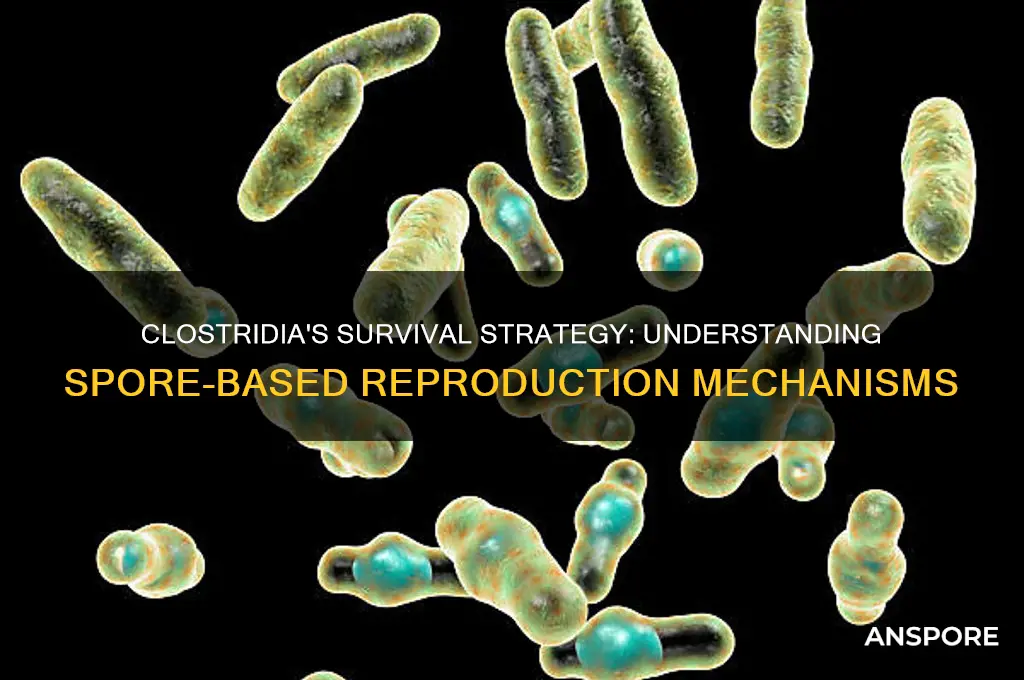

Clostridia, a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, are well-known for their ability to form highly resistant endospores under unfavorable environmental conditions. These spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing the bacteria to endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. When conditions become favorable again, the spores germinate, giving rise to new vegetative cells. This reproductive strategy is crucial for the persistence and dissemination of clostridia in various environments, including soil, water, and the gastrointestinal tracts of animals. Understanding whether and how clostridia reproduce through spores is essential for comprehending their ecology, pathogenicity, and potential control measures.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Clostridia primarily reproduce through spore formation (endospores). |

| Spore Type | Endospores (highly resistant, dormant structures). |

| Spore Location | Formed within the bacterial cell (endospore). |

| Spore Function | Survival in harsh conditions (heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Germination | Spores germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions. |

| Vegetative Reproduction | Also reproduce by binary fission under optimal conditions. |

| Spore Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, radiation, and disinfectants. |

| Spore Formation Conditions | Triggered by nutrient depletion or environmental stress. |

| Medical Significance | Spores can cause infections (e.g., Clostridium difficile). |

| Industrial Applications | Spores used in biotechnology (e.g., enzyme production). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: Clostridia form spores via a complex, multi-stage cellular differentiation process

- Spore Structure: Spores consist of a core, cortex, coat, and exosporium for protection

- Germination Triggers: Spores activate and germinate in response to specific environmental cues

- Survival Advantages: Spores enable Clostridia to withstand harsh conditions like heat and toxins

- Role in Infection: Spores facilitate Clostridia's transmission and persistence in hosts

Sporulation Process: Clostridia form spores via a complex, multi-stage cellular differentiation process

Clostridia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, are renowned for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a process known as sporulation. This complex, multi-stage cellular differentiation is a survival mechanism that allows these bacteria to endure harsh environmental conditions, including extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. The sporulation process is not merely a simple transformation but a meticulously orchestrated series of events that ensure the bacterium's long-term viability.

The initiation of sporulation in Clostridia is triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. This environmental signal prompts the bacterium to divert its energy from vegetative growth to the development of a spore. The process begins with the formation of an asymmetrically positioned septum, dividing the cell into two compartments: the smaller forespore and the larger mother cell. This spatial organization is critical, as it sets the stage for the subsequent stages of spore development.

As sporulation progresses, the forespore is engulfed by the mother cell, a process akin to phagocytosis, resulting in a double-membrane structure. The mother cell then synthesizes a thick layer of peptidoglycan, known as the cortex, around the forespore. Concurrently, the forespore begins to synthesize its own protective coat proteins, which are deposited in a precise, layered manner. This coat serves as a barrier against environmental stressors, contributing to the spore's remarkable resilience.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Clostridia sporulation is the synthesis of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a calcium-chelating agent that accumulates in the spore core. DPA plays a crucial role in maintaining the spore's structural integrity and protecting its DNA from damage. The accumulation of DPA is accompanied by the dehydration of the spore core, further enhancing its resistance to heat and radiation. This stage is particularly critical, as it transforms the spore into a metabolically dormant state, capable of surviving for extended periods.

Finally, the mature spore is released from the mother cell through lysis, marking the completion of the sporulation process. This endospore is now equipped with multiple layers of protection, including the cortex, coat, and exosporium, each contributing to its ability to withstand adverse conditions. The entire process, from initiation to completion, is a testament to the evolutionary sophistication of Clostridia, ensuring their survival in diverse and challenging environments. Understanding this intricate process not only sheds light on the biology of these bacteria but also has practical implications for industries such as food preservation, where controlling sporulation can prevent contamination.

Can You Get a Parking Ticket Using SpotHero Spots?

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Spores consist of a core, cortex, coat, and exosporium for protection

Clostridia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, are renowned for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a key survival mechanism in harsh environments. These spores are not just simple structures but intricate, multi-layered entities designed to protect the bacterial core. Understanding the spore structure is crucial, as it explains how clostridia can persist in soil, water, and even medical settings for years, posing challenges in infection control and food safety.

At the heart of the spore lies the core, housing the bacterial DNA, ribosomes, and essential enzymes. This core is dehydrated and metabolically dormant, a state that significantly enhances its resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. Surrounding the core is the cortex, a thick layer of peptidoglycan that provides structural integrity and additional protection. The cortex’s low water content further contributes to the spore’s resilience, making it impervious to many antimicrobial agents. For instance, spores can survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a process that kills most vegetative bacteria.

The coat is the next critical layer, composed of multiple proteins arranged in a crystalline structure. This layer acts as a physical barrier against enzymes and other degradative agents. Its complexity varies among species, with some clostridia having additional coat proteins that enhance adhesion or resistance. For example, *Clostridium difficile* spores have a coat that aids in gut colonization, a key factor in its pathogenicity. The outermost layer, the exosporium, is a loose-fitting, hair-like structure that provides further protection and facilitates environmental interactions. It contains proteins and carbohydrates that help spores evade the host immune system, ensuring their survival in diverse habitats.

Practical implications of this structure are significant. In healthcare, understanding spore layers helps in developing effective decontamination protocols. For instance, hydrogen peroxide vapor or peracetic acid can penetrate the exosporium and coat to inactivate spores. In food processing, spore resistance necessitates high-temperature treatments (e.g., 121°C for canned foods) to ensure safety. Home canners should follow USDA guidelines, processing low-acid foods for at least 20 minutes at 240°F to destroy spores.

In summary, the spore structure of clostridia is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation, with each layer serving a specific protective function. From the dormant core to the immune-evading exosporium, these features enable clostridia to thrive in extreme conditions. Recognizing this complexity is essential for combating spore-related infections and ensuring food safety, making it a critical area of study in microbiology and public health.

Milky Spore Overuse: Risks and Best Practices for Lawn Care

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Spores activate and germinate in response to specific environmental cues

Clostridia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, are renowned for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a key survival mechanism in harsh environments. These spores remain dormant until specific environmental cues trigger germination, a process critical for the bacteria's lifecycle. Understanding these germination triggers is essential for controlling Clostridia in various settings, from food preservation to medical treatments.

Analytical Insight: Spores of Clostridia are remarkably resilient, capable of withstanding extreme conditions such as high temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. However, germination is not a random event. Research indicates that specific factors, including temperature shifts, nutrient availability, and pH changes, act as precise triggers. For instance, a sudden increase in temperature to around 37°C (98.6°F) can signal to the spore that it has entered a favorable environment, initiating the germination process. This temperature is particularly relevant in medical contexts, as it mimics the human body temperature, highlighting the spore's adaptability to host environments.

Instructive Guide: To effectively manage Clostridia in food processing, it is crucial to manipulate these environmental cues. For example, in canning, maintaining a consistent temperature above 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes (a process known as sterilization) ensures that any spores present are destroyed. Conversely, in controlled environments like fermentation, specific nutrients such as amino acids (e.g., L-alanine at concentrations of 10-100 mM) can be added to induce germination, allowing for the subsequent inactivation of the bacteria. This dual approach—elimination through extreme conditions and controlled activation—demonstrates the importance of understanding germination triggers in practical applications.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike other spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus, Clostridia often require additional factors for germination. For example, while Bacillus spores may germinate solely in response to nutrients like L-valine, Clostridia frequently necessitate a combination of nutrients and specific environmental conditions, such as anaerobic atmospheres. This distinction underscores the unique challenges in managing Clostridia, particularly in industries where anaerobic conditions are prevalent, such as in the production of certain cheeses or in wastewater treatment.

Descriptive Example: Consider the case of Clostridium botulinum, a pathogen notorious for causing botulism. Spores of this bacterium can germinate in environments with low oxygen levels and the presence of specific sugars, such as glucose. In food preservation, this knowledge is pivotal. For instance, in the production of canned vegetables, ensuring that the canning process eliminates both spores and their germination triggers is critical. This involves not only heat treatment but also controlling the pH (typically below 4.6) and oxygen levels to create an environment inhospitable to spore activation.

Persuasive Takeaway: The precise control of germination triggers offers a powerful tool in combating Clostridia-related issues. By manipulating temperature, nutrient availability, and other environmental factors, industries can prevent spore activation and ensure safety. For individuals, understanding these triggers can inform practices such as proper food storage and handling, reducing the risk of contamination. In medical settings, this knowledge aids in the development of targeted therapies, such as antimicrobial treatments that exploit the spore's reliance on specific cues for germination. Mastery of these triggers is not just a scientific curiosity but a practical necessity for health and safety.

Can Dogs Be Allergic to Mold Spores? Symptoms and Solutions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Advantages: Spores enable Clostridia to withstand harsh conditions like heat and toxins

Clostridia, a genus of anaerobic, Gram-positive bacteria, have mastered the art of survival through their ability to form spores. These spores are not just a means of reproduction but a sophisticated survival mechanism. When faced with adverse environmental conditions such as extreme heat, desiccation, or exposure to toxins, Clostridia cells differentiate into spores, a process known as sporulation. This transformation is a strategic retreat, allowing the bacteria to enter a dormant state where metabolic activity is drastically reduced, and resistance to external stressors is maximized.

Consider the practical implications of this survival strategy in food preservation. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum*, a notorious pathogen responsible for botulism, can produce spores that withstand temperatures up to 100°C for several minutes. This resilience poses a significant challenge in the food industry, where heat treatment is a common method to eliminate pathogens. To combat this, food processors often employ a combination of heat (e.g., 121°C for 3 minutes in autoclaving) and other preservation techniques like irradiation or high-pressure processing to ensure spore inactivation. Understanding the spore’s heat resistance is crucial for designing effective sterilization protocols, particularly in canned foods where spores can survive and germinate if conditions become favorable.

From a comparative perspective, the spore’s ability to resist toxins is equally remarkable. Clostridia spores possess a thick, multilayered coat composed of proteins and peptidoglycan, which acts as a barrier against antimicrobial agents, including antibiotics and chemical disinfectants. For example, spores of *Clostridioides difficile* (formerly *Clostridium difficile*) can survive exposure to common hospital disinfectants like alcohol-based hand sanitizers, which are ineffective against them. This resistance underscores the importance of using spore-specific disinfectants, such as chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 5,000–10,000 ppm chlorine) or hydrogen peroxide, in healthcare settings to prevent *C. difficile* transmission.

A persuasive argument for studying Clostridia spores lies in their role as both a threat and a tool. While their resilience can lead to foodborne illnesses and hospital-acquired infections, the same properties make them valuable in biotechnology. For instance, spores’ resistance to harsh conditions has been exploited in the development of probiotic formulations, where they can survive the acidic environment of the stomach and deliver beneficial bacteria to the gut. Additionally, spores’ ability to remain viable for extended periods makes them ideal candidates for bioindicators in sterilization validation processes, ensuring equipment and materials are free of microbial contamination.

In conclusion, the survival advantages conferred by spores are a testament to Clostridia’s evolutionary ingenuity. By withstanding heat, toxins, and other stressors, these spores ensure the bacteria’s persistence in diverse environments. For industries and researchers, understanding this resilience is not just an academic exercise but a practical necessity for mitigating risks and harnessing potential applications. Whether in food safety, healthcare, or biotechnology, the spore’s survival capabilities demand respect and strategic countermeasures.

Rapid Bacterial Spore Growth: Fact or Fiction? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Role in Infection: Spores facilitate Clostridia's transmission and persistence in hosts

Clostridia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, are notorious for their ability to form highly resistant spores. These spores play a pivotal role in the transmission and persistence of Clostridia within hosts, making them formidable pathogens. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can survive extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and exposure to disinfectants, ensuring the bacteria’s longevity in diverse environments. This resilience allows Clostridia to persist in soil, water, and even the gastrointestinal tracts of animals, where they await favorable conditions to reactivate and cause infection.

Consider the lifecycle of *Clostridium difficile*, a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. When a host ingests *C. difficile* spores, they remain dormant as they pass through the stomach’s acidic environment. Upon reaching the intestines, the spores germinate into vegetative cells, which then produce toxins that damage the intestinal lining. This process highlights how spores act as vehicles for transmission, enabling the bacteria to bypass host defenses and establish infection. Without the spore stage, Clostridia would struggle to survive outside the host, limiting their ability to spread.

The persistence of spores in healthcare settings is particularly concerning. For instance, *C. difficile* spores can remain viable on surfaces for months, posing a risk to immunocompromised patients. Standard alcohol-based disinfectants are ineffective against spores, necessitating the use of spore-specific agents like chlorine-based cleaners. In clinical practice, strict adherence to infection control protocols, such as hand hygiene with soap and water, is critical to prevent spore transmission. Patients on prolonged antibiotic therapy, especially those over 65 years old, are at higher risk due to disrupted gut microbiota, which allows *C. difficile* to colonize more easily.

From an evolutionary perspective, spore formation is a survival strategy that ensures Clostridia’s ecological success. Spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for conditions conducive to growth. This adaptability is particularly advantageous in environments with fluctuating resources or hostile conditions. For example, in agricultural settings, spores in soil can contaminate food crops, leading to foodborne illnesses like botulism caused by *Clostridium botulinum*. Here, spores not only facilitate transmission but also act as a reservoir, maintaining the bacteria’s presence in ecosystems.

In summary, spores are indispensable to Clostridia’s role in infection, serving as both a transmission mechanism and a means of persistence. Their ability to withstand harsh conditions ensures the bacteria’s survival and spread, posing significant challenges in clinical and environmental settings. Understanding the spore lifecycle is crucial for developing targeted interventions, from improved disinfection protocols to spore-germination inhibitors. By focusing on spores, we can better combat Clostridia-related infections and mitigate their impact on public health.

Unbelievable Lifespan: How Long Can Spores Survive in Extreme Conditions?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all clostridia reproduce through spores. While many species of clostridia are known for their ability to form spores, some species do not produce spores and reproduce solely through vegetative cell division.

Clostridia spores are highly resistant structures that allow the bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This dormancy ensures their long-term survival until favorable conditions return, at which point the spores can germinate and resume growth.

Clostridia spores are notoriously resistant to standard sterilization methods, such as boiling or alcohol exposure. They typically require more extreme measures, such as autoclaving at high temperatures (e.g., 121°C for 15–30 minutes) or specific chemical treatments, to effectively destroy them.