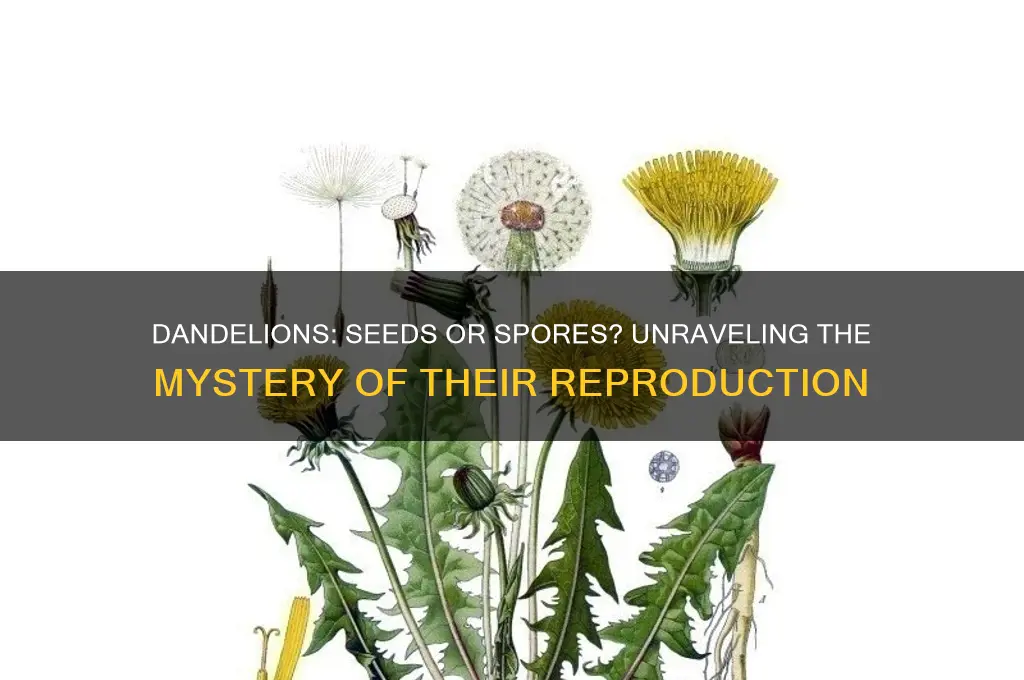

Dandelions are often recognized for their bright yellow flowers and fluffy, white seed heads, but there is sometimes confusion about how they reproduce. Unlike plants that disperse spores, such as ferns or fungi, dandelions reproduce through seeds. Each of the tiny, parachute-like structures on the white, fluffy head is actually a seed, known as an achene, equipped with a feathery pappus that allows it to be carried by the wind. This adaptation ensures widespread dispersal, making dandelions highly successful in colonizing new areas. Therefore, dandelions do not produce spores; they rely entirely on seeds for propagation.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dandelion Seed Structure: Tiny, parachute-like seeds called achenes aid wind dispersal for wide propagation

- Spores vs. Seeds: Dandelions reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

- Seed Dispersal Methods: Wind carries seeds, ensuring dandelions spread across large areas efficiently

- Life Cycle Overview: Seeds germinate, grow, flower, and produce new seeds annually

- Seedling Development: Seeds sprout quickly, forming rosettes before flowering and seeding again

Dandelion Seed Structure: Tiny, parachute-like seeds called achenes aid wind dispersal for wide propagation

Dandelions, often dismissed as weeds, are marvels of botanical engineering. Their seeds, known as achenes, are tiny, dry fruits that encapsulate a single seed. Each achene is crowned with a feathery, parachute-like structure called a pappus, which serves as a natural glider. This design is no accident—it’s a masterpiece of evolution, optimized for wind dispersal. When mature, the pappus catches the slightest breeze, carrying the seed far from its parent plant. This mechanism ensures dandelions colonize new territories efficiently, outcompeting many other plants in their ability to propagate.

To understand the achene’s role, consider its structure. The seed itself is lightweight, typically measuring less than 2 millimeters in length, while the pappus can span up to 10 millimeters. This size ratio maximizes lift-to-weight efficiency, akin to a miniature hot air balloon. Unlike spores, which are microscopic and often rely on water or animals for dispersal, dandelion seeds are self-sufficient travelers. Their design allows them to remain airborne for minutes, sometimes traveling hundreds of meters. This adaptability explains why dandelions thrive in diverse environments, from lawns to meadows.

For gardeners or educators, observing this process can be both instructive and practical. To study wind dispersal, collect a mature dandelion head and gently blow on it to see how seeds detach and float away. Alternatively, place a dandelion in a clear container and observe how seeds disperse when air currents are introduced. This simple experiment demonstrates the principles of aerodynamics in nature. For those managing dandelion populations, understanding this mechanism highlights the futility of manual removal—seeds can travel far beyond the visible plant.

Comparatively, dandelion seeds differ starkly from spores, which are reproductive units produced by ferns, fungi, and some plants. Spores are unicellular and require specific conditions to germinate, whereas dandelion seeds are multicellular embryos encased in protective achenes. This distinction is critical for identification and management. For instance, herbicides targeting spore-producing plants may be ineffective on dandelions, which rely on seeds. Recognizing these differences ensures more precise control strategies, whether in agriculture or landscaping.

In practical terms, the dandelion’s seed structure offers lessons in sustainability and design. Engineers have drawn inspiration from the pappus to develop micro-drones and biodegradable packaging. Gardeners can mimic this natural dispersal by creating windbreaks or using lightweight seed coatings for their plants. For children, dandelions provide an accessible entry point to botany—encourage them to observe how seeds fly or germinate in soil. By appreciating the achene’s ingenuity, we not only demystify dandelions but also gain insights into solving human challenges through biomimicry.

Can Spores Travel on Paper? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Seeds: Dandelions reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

Dandelions, those ubiquitous yellow-flowered plants often dismissed as weeds, rely on seeds for reproduction, not spores. This distinction is crucial for understanding their life cycle and how they spread so effectively. Unlike ferns or fungi, which disperse tiny, lightweight spores to colonize new areas, dandelions produce seeds equipped with feathery structures called pappus. These pappus act as parachutes, allowing the seeds to travel significant distances on the wind, ensuring the plant’s survival and proliferation across diverse environments.

To grasp the difference, consider the mechanics of seed versus spore dispersal. Spores, such as those produced by ferns, are microscopic and require moisture to germinate, making them dependent on specific environmental conditions. In contrast, dandelion seeds are larger, more resilient, and can germinate in a variety of soils and climates. This adaptability explains why dandelions thrive in lawns, cracks in sidewalks, and even barren soil, while ferns are confined to shaded, moist habitats. For gardeners or landscapers, understanding this difference is key to managing dandelion growth effectively.

From a practical standpoint, knowing that dandelions reproduce via seeds offers actionable strategies for control. Pulling the entire plant, including its deep taproot, prevents seed production and reduces future spread. Alternatively, mowing before the seeds mature can limit dispersal. For those who appreciate dandelions’ ecological benefits—such as providing early-season nectar for pollinators—allowing controlled growth in designated areas can strike a balance. Unlike spore-producing plants, which are harder to contain due to their microscopic dispersal units, dandelions’ seed-based reproduction makes them more manageable with targeted interventions.

Finally, the comparison between dandelion seeds and fern spores highlights broader evolutionary strategies in the plant kingdom. Seeds represent a more advanced reproductive mechanism, encapsulating nutrients and protective layers to support embryonic plants. Spores, while simpler, rely on sheer numbers and favorable conditions to succeed. This distinction underscores why dandelions are so successful in human-altered landscapes, while ferns remain niche players in specific ecosystems. Whether viewed as a nuisance or a marvel of adaptation, dandelions’ seed-based reproduction is a testament to their resilience and resourcefulness.

Can Sceptile Learn Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities in Pokémon

You may want to see also

Seed Dispersal Methods: Wind carries seeds, ensuring dandelions spread across large areas efficiently

Dandelions are masters of dispersal, and their seeds are perfectly designed for wind travel. Each seed is attached to a delicate, white, hair-like structure called a pappus, which acts as a miniature parachute. When the seed head matures and dries, the slightest breeze can catch these pappus-equipped seeds, lifting them into the air and carrying them far from the parent plant. This adaptation ensures that dandelions can colonize new areas quickly and efficiently, even in environments where other plants might struggle to spread.

Consider the mechanics of this process: the pappus reduces the seed’s terminal velocity, allowing it to stay airborne longer and travel greater distances. Studies have shown that dandelion seeds can be carried by wind currents for over a kilometer under ideal conditions. This method of dispersal is not just random but highly effective, as it maximizes the plant’s ability to reach open, sunny areas where it thrives. For gardeners or landowners, this means that a single dandelion can quickly become a widespread issue if left unchecked.

To combat this natural dispersal mechanism, practical steps can be taken. Regularly mowing lawns or fields before dandelions go to seed can prevent the formation of seed heads. If seeds have already developed, removing the entire plant, including the root, ensures it cannot regrow. For those who appreciate dandelions but want to control their spread, planting them in contained areas or pots can limit their dispersal. Understanding the wind’s role in seed dispersal highlights the importance of timing and proactive management.

Comparatively, other plants rely on animals, water, or explosive mechanisms to disperse seeds, but dandelions’ wind-based strategy is uniquely efficient. Unlike spores, which are microscopic and often produced in vast quantities, dandelion seeds are larger and fewer in number, yet their dispersal is no less effective. This balance between seed size and dispersal method allows dandelions to dominate landscapes without relying on external agents. It’s a testament to the plant’s evolutionary success and a challenge for those seeking to control its spread.

Finally, appreciating the elegance of dandelion seed dispersal can shift perspectives on this often-maligned plant. While many view dandelions as weeds, their ability to thrive and spread is a marvel of natural engineering. For educators or parents, observing dandelion seeds in action provides a hands-on lesson in botany and ecology. Encourage children to blow on a dandelion seed head and watch the seeds disperse—it’s a simple yet powerful way to demonstrate how plants adapt to their environment. Whether you love them or loathe them, dandelions’ wind-driven dispersal is a fascinating example of nature’s ingenuity.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Overview: Seeds germinate, grow, flower, and produce new seeds annually

Dandelions, often dismissed as weeds, are marvels of botanical efficiency. Their life cycle is a testament to resilience and adaptability, driven by seeds rather than spores. Each year, these plants follow a precise sequence: germination, growth, flowering, and seed production. This annual cycle ensures their proliferation across lawns, fields, and cracks in pavement, making them nearly impossible to eradicate. Understanding this process reveals not just their survival strategy but also their ecological role and potential benefits.

Consider the germination phase, where a dandelion seed, carried by wind or animals, finds fertile soil. Within days, under optimal conditions—moisture and warmth—the seed sprouts. This stage is critical, as it determines the plant’s future vigor. Gardeners and landscapers often underestimate the importance of this early phase, focusing instead on mature plants. Yet, disrupting germination through mulching or soil disruption can significantly reduce dandelion populations. For instance, applying a 3-inch layer of mulch in early spring can block sunlight, preventing seeds from establishing.

As the plant grows, it develops a deep taproot, a feature that distinguishes dandelions from many other weeds. This root not only anchors the plant but also stores nutrients, enabling it to survive harsh conditions. By the time it flowers, the dandelion has become a powerhouse of energy. The bright yellow blooms are not just aesthetically striking but also functional, attracting pollinators like bees and butterflies. This stage is a reminder of the plant’s dual nature: a nuisance to some, a resource to others. For those interested in foraging, the flowers can be harvested to make tea or wine, though it’s essential to ensure they’re free from pesticides.

The final stage—seed production—is where dandelions showcase their ingenuity. Each flower head transforms into a spherical cluster of seeds, each equipped with a parachute-like structure called a pappus. This design allows seeds to travel remarkable distances, often miles, on the slightest breeze. Here lies the challenge for those seeking to control them: a single plant can produce up to 2,000 seeds annually. To mitigate spread, remove flower heads before they turn white and disperse seeds. Alternatively, mowing regularly can prevent flowering altogether, though this requires diligence.

In conclusion, the dandelion’s life cycle is a masterclass in survival, optimized for annual renewal. By understanding each phase—germination, growth, flowering, and seed production—we can appreciate both their ecological value and the challenges they pose. Whether viewed as a weed or a wildflower, the dandelion’s cycle offers lessons in adaptability and resourcefulness, reminding us that even the most common plants have extraordinary stories to tell.

Spore Syringe Shelf Life: Fridge Storage Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Seedling Development: Seeds sprout quickly, forming rosettes before flowering and seeding again

Dandelions are prolific seed producers, and their seedling development is a rapid, efficient process. Within days of germination, seeds sprout quickly, forming rosettes—a low-lying cluster of leaves—that serve as the plant’s primary growth stage. This rosette phase is critical for establishing a strong root system and storing energy before the plant transitions to flowering. Unlike spore-based reproduction, which relies on wind dispersal and chance, dandelion seeds are encased in a parachute-like structure called a pappus, ensuring targeted dispersal and higher germination rates. This seed-driven strategy allows dandelions to colonize new areas swiftly, making them a resilient and widespread species.

To observe this process, sow dandelion seeds in well-drained soil, keeping the temperature between 50°F and 65°F for optimal germination. Within 7 to 14 days, seedlings will emerge, forming rosettes that expand over 2 to 3 weeks. During this phase, ensure consistent moisture but avoid overwatering to prevent root rot. The rosette stage typically lasts 4 to 6 weeks, after which the plant allocates energy to flowering. This timeline underscores the efficiency of dandelion seedling development, enabling multiple growth cycles within a single growing season.

Comparatively, spore-based plants like ferns rely on moisture-dependent germination and lack the protective structures of seeds. Dandelions, however, thrive in diverse conditions due to their seeds’ adaptability. The rosette phase acts as a survival mechanism, allowing the plant to endure harsh conditions before flowering. This contrasts with spore-dependent species, which often require specific environmental cues to propagate successfully. Dandelions’ seed-based strategy ensures their persistence, even in disturbed or nutrient-poor soils.

For gardeners or landscapers, understanding this development cycle is key to managing dandelion populations. Hand-pulling rosettes before they flower can prevent seeding, reducing future growth. Alternatively, applying pre-emergent herbicides in early spring can inhibit seed germination. However, if you’re cultivating dandelions for their edible leaves or medicinal properties, allow rosettes to mature for harvest. The rapid progression from seed to rosette to flower highlights the importance of timely intervention, whether for control or cultivation.

In conclusion, dandelion seedling development is a testament to the plant’s evolutionary success. From quick sprouting to rosette formation, each stage is optimized for survival and reproduction. Unlike spore-based plants, dandelions leverage seeds to dominate landscapes, making their lifecycle a fascinating study in botanical efficiency. Whether viewed as a weed or a resource, understanding this process empowers both eradication and appreciation of this ubiquitous plant.

Can Spores Survive Anaerobic Conditions? Exploring Their Resilience and Limits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Dandelions reproduce using seeds, not spores.

Dandelion seeds are small, with a fluffy, white, parachute-like structure called a pappus that helps them disperse in the wind.

Yes, the fluffy white balls are actually clusters of dandelion seeds, each with its own pappus for wind dispersal.

No, dandelions do not produce spores. They are flowering plants that rely solely on seeds for reproduction.

Dandelion seeds are produced from flowers and contain a tiny plant embryo, while spores are microscopic reproductive units produced by non-flowering plants like ferns and fungi.