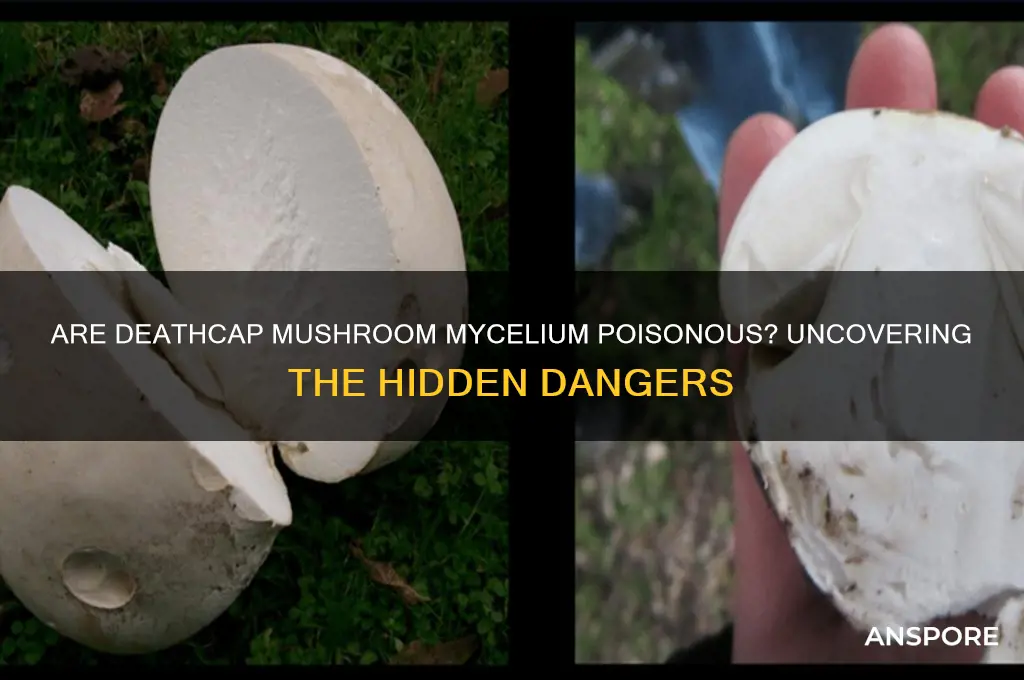

The Death Cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is one of the most toxic fungi in the world, responsible for numerous fatal poisonings due to its potent toxins, including amatoxins. While the fruiting body (the visible mushroom) is well-known for its deadly properties, questions often arise about whether the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus that grows underground—also contains these poisons. Research indicates that the mycelium of the Death Cap does indeed produce amatoxins, though the concentration may vary compared to the fruiting body. This means that even handling or ingesting the mycelium can pose a significant health risk, underscoring the importance of caution when dealing with any part of this highly toxic fungus.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | Yes, deathcap mushroom mycelium contains the same toxins (amatoxins) as the fruiting body. |

| Toxins Present | Amatoxins (e.g., α-amanitin, β-amanitin), phallotoxins. |

| Toxicity Level | Highly toxic; ingestion can be fatal. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Delayed onset (6–24 hours), gastrointestinal distress, liver and kidney failure, potential death. |

| Mycelium vs. Fruiting Body | Mycelium contains the same toxins as the fruiting body, though concentrations may vary. |

| Risk of Exposure | Handling or ingesting mycelium can be dangerous, especially if not properly identified. |

| Medical Treatment | Immediate medical attention required; supportive care, activated charcoal, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation. |

| Prevention | Avoid contact or ingestion of unknown fungi, including mycelium, especially in the wild. |

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides (mycelium). |

| Common Name | Deathcap mushroom mycelium. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Toxic Compounds in Mycelium: Does deathcap mycelium contain amatoxins like the fruiting body

- Mycelium vs. Mushroom Toxicity: Are poison levels in mycelium similar to mature mushrooms

- Amatoxin Production: Do deathcap mycelium actively produce deadly amatoxins during growth

- Safety of Handling Mycelium: Is contact with deathcap mycelium dangerous to humans or pets

- Mycelium in Contaminated Soil: Can toxic mycelium spread amatoxins through soil or substrates

Toxic Compounds in Mycelium: Does deathcap mycelium contain amatoxins like the fruiting body?

The deathcap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is notorious for its deadly fruiting body, which contains amatoxins—a group of cyclic octapeptides responsible for severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to death if ingested. However, the question of whether its mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, also harbors these toxins remains less explored. Amatoxins are primarily associated with the fruiting body, but recent studies suggest that mycelium may not be entirely free of these compounds, raising concerns for cultivators and foragers alike.

Analyzing the presence of amatoxins in deathcap mycelium requires understanding the fungus’s life cycle. Amatoxins are believed to be synthesized during the fruiting stage, but mycelium serves as the foundation for toxin production. Laboratory studies have detected trace amounts of amatoxins in deathcap mycelium, though concentrations are significantly lower than in the fruiting body. For instance, one study found α-amanitin levels in mycelium at approximately 0.01–0.1% of those in mature mushrooms. While these amounts may not be immediately lethal, prolonged exposure or accidental ingestion could pose risks, particularly for individuals with compromised immune systems or children.

From a practical standpoint, anyone handling deathcap mycelium—whether in research or cultivation—should adhere to strict safety protocols. Wear gloves, use a well-ventilated area, and avoid direct contact with skin or mucous membranes. If cultivating non-toxic mushroom species, ensure no cross-contamination occurs, as even trace amatoxins can accumulate over time. For foragers, it’s critical to identify mushrooms accurately, as mycelium in soil may indicate the presence of toxic species nearby. A single deathcap contains enough amatoxins to kill an adult, so caution is paramount.

Comparatively, other toxic mushrooms like the destroying angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) also produce amatoxins, but their mycelium has shown even lower toxin levels than the deathcap’s. This suggests variability among species, though the principle remains: mycelium should not be assumed safe. Unlike the fruiting body, mycelium’s toxin content is less predictable, making it a potential hidden danger in environments where deathcaps thrive.

In conclusion, while deathcap mycelium contains amatoxins at lower concentrations than the fruiting body, it is not toxin-free. This knowledge underscores the need for vigilance in handling and identifying fungi, whether in the wild or in controlled settings. Understanding the risks associated with mycelium ensures safer practices and highlights the complexity of fungal toxicity beyond the visible mushroom.

Identifying Backyard Mushrooms: Are They Safe or Poisonous to Humans?

You may want to see also

Mycelium vs. Mushroom Toxicity: Are poison levels in mycelium similar to mature mushrooms?

The deathcap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is notorious for its deadly toxins, primarily amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage. While mature mushrooms are well-documented as lethal, the toxicity of their mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—remains less explored. Understanding whether the mycelium contains similar poison levels is critical for foragers, researchers, and anyone handling fungal materials. Amatoxins are heat-stable and not destroyed by cooking, making even trace amounts in mycelium a potential hazard.

Analyzing toxin distribution reveals that amatoxins are primarily synthesized in the fruiting bodies (mushrooms) of *Amanita phalloides*. However, mycelium is not entirely toxin-free. Studies suggest that mycelium may contain lower, but still detectable, levels of amatoxins. For instance, a 2018 study found that mycelium cultures of *Amanita phalloides* contained approximately 10–20% of the amatoxin concentration found in mature mushrooms. While this is significantly less, ingestion of a sufficient quantity of mycelium could still pose a risk, particularly for children or pets.

From a practical standpoint, handling deathcap mycelium requires caution. Foragers should avoid assuming mycelium is safe, especially when cultivating or studying these fungi. Wearing gloves and ensuring proper ventilation are essential precautions. If accidental ingestion occurs, immediate medical attention is necessary, as symptoms of amatoxin poisoning (e.g., nausea, vomiting, liver failure) can appear within 6–24 hours. Even small doses, such as 0.1 mg/kg of body weight, can be fatal in humans.

Comparatively, the toxicity of mycelium versus mature mushrooms highlights a critical difference in risk management. While mature deathcaps are easily identifiable and avoided, mycelium is often invisible, growing underground or in substrates. This makes accidental exposure more likely, particularly in contaminated soil or compost. For example, gardeners using mushroom compost should verify its source to avoid *Amanita phalloides* mycelium. Unlike mature mushrooms, mycelium lacks visual cues, making it a hidden danger.

In conclusion, while deathcap mycelium contains lower toxin levels than mature mushrooms, it is not harmless. The presence of amatoxins, even in reduced concentrations, necessitates caution in handling and exposure. Awareness of this distinction is vital for safety, particularly in environments where mycelium may be present but unseen. Treat deathcap mycelium with the same respect as its deadly fruiting bodies.

Reheating Mushrooms: Safe Practice or Poisonous Mistake?

You may want to see also

Amatoxin Production: Do deathcap mycelium actively produce deadly amatoxins during growth?

The deathcap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is infamous for its lethal amatoxins, which are responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide. While the fruiting bodies of this fungus are well-documented sources of these toxins, the question of whether the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—actively produces amatoxins during growth remains a critical yet less explored area. Understanding this could have significant implications for safety in cultivation, foraging, and even accidental exposure scenarios.

From an analytical perspective, amatoxins are cyclic octapeptides primarily synthesized during the fruiting body development stage of *Amanita phalloides*. Research suggests that the genes responsible for amatoxin production are expressed more prominently in the fruiting bodies than in the mycelium. However, this does not definitively rule out mycelial production. Studies using PCR and LC-MS techniques have detected amatoxin precursors in mycelial cultures, indicating that the biosynthetic pathway is active, albeit at lower levels. This raises the question: is the mycelium a latent threat, or does it simply lack the environmental cues to produce toxins at dangerous concentrations?

For those cultivating mushrooms or studying mycology, understanding the potential risks of handling deathcap mycelium is essential. While the mycelium may not produce amatoxins at the same lethal levels as the fruiting bodies, even trace amounts can pose risks, especially with prolonged exposure. For instance, a dose of just 0.1 mg/kg of alpha-amanitin, a primary amatoxin, can be fatal to humans. Practical precautions include using gloves, masks, and proper ventilation when handling mycelial cultures, particularly in laboratory or commercial settings. Additionally, avoiding cross-contamination with edible mushroom species is critical to prevent accidental poisoning.

Comparatively, other toxic fungi, such as *Galerina marginata*, also produce amatoxins, but their mycelium has been less studied. This highlights a broader gap in mycotoxin research: the focus on fruiting bodies often overshadows the potential hazards of mycelial growth. By contrast, some edible mushrooms, like *Agaricus bisporus*, have mycelium that is safe to handle, underscoring the importance of species-specific knowledge. This comparative lens suggests that while deathcap mycelium may not be as toxic as its fruiting bodies, it warrants caution and further investigation.

In conclusion, while the mycelium of *Amanita phalloides* does not appear to actively produce deadly amatoxins at the same levels as the fruiting bodies, it is not entirely toxin-free. The presence of amatoxin precursors in mycelial cultures indicates that the biosynthetic pathway is functional, albeit less active. For practical safety, treating deathcap mycelium with the same caution as the fruiting bodies is advisable, especially in controlled environments. This nuanced understanding bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application, ensuring safer practices in both scientific and recreational contexts.

Are Earth Ball Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safety of Handling Mycelium: Is contact with deathcap mycelium dangerous to humans or pets?

The deathcap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is notorious for its deadly toxins, primarily amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage in humans and animals. While much attention is focused on the fruiting body, the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—raises questions about its safety. Unlike the mushroom itself, mycelium is less studied in terms of toxicity, but its potential risks cannot be overlooked. Amatoxins are produced by the fungus during its life cycle, and while the concentration in mycelium is generally lower than in the mature mushroom, it still poses a hazard if ingested or improperly handled.

Handling deathcap mycelium requires caution, particularly for those cultivating fungi or working in environments where it may be present. Direct skin contact with the mycelium is unlikely to cause harm, as amatoxins are not absorbed through intact skin. However, the risk escalates if the mycelium is inhaled or ingested. For instance, accidental ingestion of contaminated soil or spores could lead to poisoning, especially in children or pets who are more likely to put things in their mouths. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning, such as nausea, vomiting, and liver failure, can appear within 6–24 hours, making prompt medical intervention critical.

Pets, particularly dogs, are at higher risk due to their foraging behavior. Even small amounts of deathcap mycelium can be lethal to animals, as their smaller body mass makes them more susceptible to toxins. If you suspect your pet has come into contact with deathcap mycelium, immediate veterinary care is essential. Preventive measures include keeping pets away from areas where deathcap mushrooms are known to grow and regularly inspecting your yard for fungal growth.

For humans, the key to safety lies in proper identification and handling. If you are a mycologist or hobbyist working with fungi, always wear gloves and a mask when handling unknown mycelium. Avoid touching your face or eating without thorough handwashing. While the mycelium is less toxic than the fruiting body, it is not risk-free, and cross-contamination can occur if tools or surfaces are not sanitized. Educating oneself about the appearance and habitat of deathcap mushrooms is crucial, as misidentification can have fatal consequences.

In conclusion, while deathcap mycelium is less dangerous than the mushroom itself, it still contains toxins that pose a risk to humans and pets, particularly through ingestion. Cautious handling, proper protective measures, and awareness of potential exposure are essential to mitigate risks. When in doubt, consult experts or avoid contact altogether, as the consequences of poisoning are severe and often irreversible.

Ohio's Poisonous Mushrooms: Identifying Deadly Fungi in the Buckeye State

You may want to see also

Mycelium in Contaminated Soil: Can toxic mycelium spread amatoxins through soil or substrates?

The deathcap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is notorious for its deadly amatoxins, which are responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. While much attention is given to the fruiting bodies, the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—raises critical questions about its role in toxin dissemination. Amatoxins are primarily synthesized in the mushroom’s tissues, but recent studies suggest that mycelium may also produce these toxins under certain conditions. This raises concerns about contaminated soil, where mycelial networks can spread undetected, potentially releasing amatoxins into the environment. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for assessing risks in agricultural, forestry, and urban settings where deathcap mycelium might be present.

In contaminated soil, mycelium acts as a silent conduit, extending its network through substrates in search of nutrients. If toxic mycelium is present, it could theoretically release amatoxins into the soil, affecting nearby plants, microorganisms, and even groundwater. However, the concentration of amatoxins in mycelium is significantly lower than in the fruiting bodies, typically ranging from 10% to 30% of the levels found in mature mushrooms. This dilution reduces immediate toxicity but does not eliminate risk, especially in prolonged exposure scenarios. For instance, livestock grazing in contaminated areas or humans handling tainted soil could accumulate toxins over time, leading to health issues.

To mitigate risks, soil remediation strategies must consider mycelial networks. One effective method is heat treatment, where soil is raised to temperatures above 60°C (140°F) for several hours to denature amatoxins and kill mycelium. Another approach is biological control, introducing competitive fungi or bacteria that outcompete deathcap mycelium. For home gardeners, rotating crops and avoiding compost from unknown sources can prevent mycelial colonization. Testing soil for amatoxin presence using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) kits is also recommended, particularly in regions where deathcaps are endemic.

Comparatively, while mycelium’s toxin-spreading potential is lower than that of fruiting bodies, its persistence in soil poses unique challenges. Unlike mushrooms, which decompose within weeks, mycelium can survive for years, continually releasing trace amounts of amatoxins. This contrasts with other toxic fungi, such as *Claviceps purpurea* (ergot), whose toxins are primarily confined to sclerotia. The deathcap’s mycelium, however, remains active even in the absence of fruiting, making it a stealthy contaminant. This underscores the need for targeted research into mycelial toxin production and its environmental impact.

In conclusion, while deathcap mycelium contains amatoxins at lower concentrations than fruiting bodies, its ability to spread through soil or substrates poses a latent threat. Practical measures, from soil testing to remediation techniques, can help manage this risk. Awareness and proactive management are key to preventing toxin dissemination in contaminated environments, ensuring safety for both ecosystems and human activities.

Poisonous Mushrooms in Pennsylvania: Identifying Deadly Fungi in the Wild

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Deathcap mushroom mycelium contains the same deadly toxins, including amatoxins, as the fruiting bodies.

Yes, handling Deathcap mycelium can be dangerous, as the toxins are present in all parts of the fungus, including the mycelium.

Cultivating Deathcap mycelium should only be done in a controlled laboratory setting with proper safety measures, as all parts of the fungus are toxic.

No, cooking or processing does not remove the toxicity of Deathcap mycelium, as amatoxins are heat-stable and remain lethal.