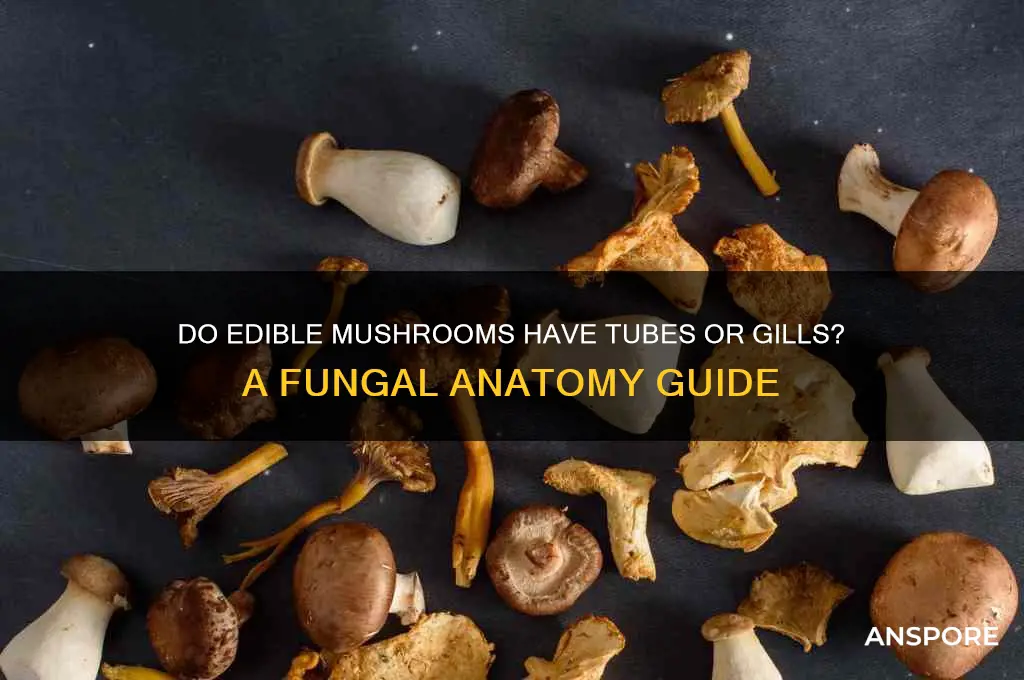

Edible mushrooms exhibit a variety of structures for spore production, with tubes and gills being two common types. Gills, found in mushrooms like the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), are thin, blade-like structures located under the cap that release spores. In contrast, tubes, characteristic of boletes such as the porcini (*Boletus edulis*), are sponge-like structures that line the underside of the cap and contain pores through which spores are dispersed. Understanding whether an edible mushroom has tubes or gills is crucial for identification, as it helps distinguish between different species and ensures safe foraging.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Tube Presence | Some edible mushrooms have tubes (pores) instead of gills, such as porcini (Boletus edulis) and chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius). |

| Gill Presence | Many edible mushrooms have gills, like button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus), shiitake (Lentinula edodes), and oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus). |

| Spore Release | Tubes release spores through pores, while gills release spores from their edges. |

| Texture | Tubes are softer and spongy, while gills are more delicate and blade-like. |

| Identification | Tubes are a key feature for identifying Boletaceae family mushrooms, while gills are common in Agaricaceae and other families. |

| Examples of Tube Fungi | Porcini, chanterelles, lion's mane (Hericium erinaceus). |

| Examples of Gill Fungi | Button mushrooms, shiitake, portobello, and enoki (Flammulina velutipes). |

| Culinary Use | Both tube and gill mushrooms are widely used in cooking, with unique textures and flavors. |

| Safety Note | Always properly identify mushrooms before consumption, as some toxic species may have tubes or gills. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Tube vs. Gill Structures: Understanding the physical differences between tubes and gills in mushrooms

- Edible Mushroom Types: Identifying common edible mushrooms with tubes or gills

- Tubes in Boletes: Exploring tube-bearing mushrooms like boletes and their edibility

- Gills in Agarics: Examining gill-bearing mushrooms like agarics and their safety for consumption

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Spotting poisonous mushrooms that mimic tube or gill structures of edible species

Tube vs. Gill Structures: Understanding the physical differences between tubes and gills in mushrooms

Mushrooms, with their diverse structures, often leave foragers puzzled about edibility. One key distinction lies in their underside: tubes versus gills. Tubes, or pores, are tiny openings found on the underside of mushrooms like boletes, resembling a sponge. Gills, in contrast, are thin, blade-like structures seen in species such as agarics, often radiating outward like the ribs of an umbrella. Understanding this difference is crucial, as it can help differentiate between edible varieties and their toxic look-alikes.

Analyzing these structures reveals more than just physical traits. Tubes typically indicate a mushroom belongs to the Boletaceae family, many of which are edible, though exceptions like the Satan’s Bolete exist. Gills, however, are more common and found in a broader range of families, including both safe (e.g., button mushrooms) and dangerous (e.g., Amanita species) varieties. Foraging tip: Always check the color and consistency of tubes or gills, as these can provide additional clues to a mushroom’s identity.

From a practical standpoint, identifying tubes or gills is a foundational step in mushroom foraging. For beginners, focus on boletes with tubes if you’re uncertain, as they generally pose less risk. However, never rely solely on this feature; always cross-reference with other characteristics like cap color, spore print, and habitat. Pro tip: Carry a small magnifying glass to inspect these structures closely, as details like pore size or gill attachment can be decisive.

Comparatively, tubes and gills serve the same biological purpose—releasing spores for reproduction—but their distinct forms evolved to suit different environments. Tubes are often found in mushrooms growing in symbiotic relationships with trees, while gilled mushrooms are more adaptable to various substrates. This evolutionary divergence highlights why certain families are more predictable in terms of edibility, offering a scientific lens to safer foraging practices.

In conclusion, mastering the tube-gill distinction is a cornerstone of mushroom identification. While tubes generally signal a safer bet, especially in boletes, gills demand meticulous scrutiny due to their association with both edible and toxic species. Always approach foraging with caution, armed with knowledge, tools, and a willingness to learn. Remember, no single feature guarantees edibility—combine observations for a confident identification.

Are Mushrooms with Black Gills Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Edible Mushroom Types: Identifying common edible mushrooms with tubes or gills

Mushrooms with tubes, or pores, under their caps are often referred to as boletes, and many of them are edible. One of the most well-known examples is the King Bolete (*Boletus edulis*), prized for its meaty texture and nutty flavor. Unlike gilled mushrooms, boletes have a spongy layer of tubes that release spores. When identifying edible boletes, look for a thick, sturdy stem and a cap that may range in color from brown to white. A key feature is the absence of a ring on the stem and the presence of a bulbous base. Always avoid boletes with red pores or a slimy cap, as these can be toxic.

Gilled mushrooms, on the other hand, are more diverse, and identifying edible ones requires careful attention to detail. The Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) is a prime example, known for its golden color and forked, wavy gills. These gills run down the stem, a unique feature that distinguishes chanterelles from other mushrooms. When foraging, ensure the gills are not brittle and that the mushroom has a fruity aroma. Another gilled edible is the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which grows in clusters on wood and has a fan-shaped cap with decurrent gills. Both of these mushrooms are safe for consumption and widely used in culinary applications.

While tubes and gills are primary identifiers, other characteristics must be considered for accurate identification. For instance, the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) has neither tubes nor gills but instead features cascading spines that resemble a lion’s mane. This edible mushroom is not only unique in appearance but also valued for its cognitive benefits. Always cross-reference multiple features, such as spore color, habitat, and season, to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes. For beginners, it’s advisable to forage with an experienced guide or use a reliable field guide.

Practical tips for safe foraging include carrying a knife for clean cuts, a basket for airflow, and gloves to avoid skin irritation. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If in doubt, consult a mycologist or use a mushroom identification app. Cooking edible mushrooms thoroughly is essential, as some can cause digestive issues when raw. For example, morels (*Morchella* spp.), which have a honeycomb-like cap, should always be cooked to eliminate potential toxins. Incorporating these practices ensures a safe and rewarding mushroom-hunting experience.

Are Ghost Mushrooms Edible? Unveiling the Truth About Omphalotus Olearius

You may want to see also

Tubes in Boletes: Exploring tube-bearing mushrooms like boletes and their edibility

Boletes, a distinctive group of fungi, are characterized by their spongy underside composed of tubes, setting them apart from gilled mushrooms. These tubes, which release spores, are a key identifier for foragers. Unlike the delicate gills of Agaricus species, bolete tubes are robust and often brightly colored, ranging from yellow to green or even red. This unique feature not only aids in identification but also hints at their edibility, as many boletes are prized for their culinary value. However, not all tube-bearing mushrooms are safe to eat, making careful examination essential.

When foraging for boletes, start by inspecting the tubes. Young specimens have tubes that are tightly packed and may appear white or pale, while mature ones display more vivid colors. A practical tip is to gently press the tubes; if they bruise blue or brown, it could indicate a less desirable species, such as the bitter *Tylopilus felleus*. Edible boletes, like the coveted *Boletus edulis* (porcini), typically have tubes that remain pale or turn slightly yellow with age. Always cross-reference with a reliable field guide or app to confirm identification.

Edibility in boletes is closely tied to their tube structure and overall appearance. For instance, the *Suillus* genus, often found near conifers, has tubes that are decurrent (running down the stem) and is generally edible but may have a slimy cap, which some find unappealing. In contrast, the *Boletus* genus, with its distinct tubes and stout stature, includes many edible species. A cautionary note: avoid boletes with red pores or those that stain blue immediately upon cutting, as these traits often correlate with toxicity.

Foraging for tube-bearing mushrooms like boletes requires patience and attention to detail. Begin by familiarizing yourself with local species through guided walks or online resources. When harvesting, use a knife to cut the mushroom at the base, preserving the mycelium for future growth. Cook boletes thoroughly, as some species can cause digestive upset when raw. Incorporate them into dishes like risottos or soups to enhance flavor, but always consume in moderation, especially when trying a species for the first time. With proper knowledge and caution, boletes offer a rewarding culinary experience for the discerning forager.

Can You Eat Lawn Mushrooms? A Guide to Edible Varieties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gills in Agarics: Examining gill-bearing mushrooms like agarics and their safety for consumption

Agarics, a diverse group of gill-bearing mushrooms, are among the most recognizable fungi in the world. Their distinctive caps and gills make them a common sight in forests, fields, and even urban areas. But what exactly are these gills, and how do they factor into the safety and identification of edible agarics? Gills are the radiating, blade-like structures found on the underside of the mushroom cap, serving as the primary site for spore production. Unlike tube-bearing mushrooms, such as boletes, agarics rely on gills to disperse their spores, a feature that is both taxonomically significant and visually striking. Understanding the role and appearance of gills is crucial for anyone interested in foraging edible mushrooms, as it helps distinguish safe species from their toxic counterparts.

When examining agarics for consumption, the gills are a key identifier. Edible species like the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) and the meadow mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*) have gills that change color as they mature, typically progressing from pink to brown. This color shift is a natural process tied to spore development and is not an indicator of spoilage. However, foragers must be cautious, as some toxic mushrooms, such as the deadly *Galerina marginata*, also have gills that darken with age. To avoid confusion, always cross-reference gill characteristics with other features, such as cap color, stem structure, and habitat. For instance, edible agarics often have a fleshy, white stem and a cap that bruises yellow or brown when handled, whereas toxic species may lack these traits.

One practical tip for assessing gill-bearing mushrooms is to observe their attachment to the stem. In edible agarics, gills are typically free, notched, or attached to the stem without extending down it. This contrasts with toxic species, where gills may be closely attached or even decurrent (running down the stem). Additionally, the spacing and thickness of gills can provide clues. Edible agarics often have crowded, thin gills, while toxic species may have widely spaced or unusually thick ones. For beginners, it’s advisable to start with easily identifiable species and consult a field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushroom.

Despite their importance, gills alone are not a definitive marker of edibility. Some toxic mushrooms, like the Amanita species, also have gills and can resemble edible agarics. To ensure safety, foragers should adopt a multi-step approach: first, verify the mushroom’s overall morphology; second, check for specific gill characteristics; and finally, perform a spore print test. A spore print involves placing the cap gill-side down on paper overnight to observe spore color, which can help confirm the mushroom’s identity. For example, edible agarics typically produce brown or black spores, while toxic species may produce white or colored spores.

In conclusion, gills are a defining feature of agarics and play a critical role in their identification and safety assessment. While not a standalone indicator of edibility, understanding gill characteristics—such as color, attachment, and spacing—can significantly reduce the risk of misidentification. Foragers should combine this knowledge with other identification techniques and exercise caution, especially when dealing with unfamiliar species. By mastering the nuances of gill-bearing mushrooms, enthusiasts can safely enjoy the bounty of edible agarics while avoiding the dangers of their toxic look-alikes.

Are Crown Tip Coral Mushrooms Edible? A Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Spotting poisonous mushrooms that mimic tube or gill structures of edible species

Edible mushrooms often feature distinct tube or gill structures, but these very characteristics can be mimicked by toxic look-alikes, posing a serious risk to foragers. For instance, the edible chanterelle, known for its forked gills, has a dangerous doppelgänger in the jack-o’lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), which displays similar gills but causes severe gastrointestinal distress. Recognizing these structural similarities is the first step in avoiding a potentially fatal mistake.

To spot toxic mimics, focus on subtle differences in color, texture, and habitat. While the edible lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) has cascading, tooth-like structures (a form of modified gills), its toxic counterpart, the split-gill mushroom (*Schizophyllum commune*), lacks the same creamy white hue and grows on wood rather than trees. Always note the substrate—edible species like morels thrive in specific environments, whereas their poisonous look-alikes, such as false morels, often appear in disturbed soil or near decaying matter.

A critical caution: never rely solely on structural features. Toxic mushrooms like the deadly galerina (*Galerina marginata*) closely resemble edible honey mushrooms (*Armillaria mellea*) in their gill structure and growth pattern. Ingesting just one galerina can cause liver failure within 24–48 hours. Always cross-reference multiple identifiers, such as spore color (collected by placing the cap on paper overnight) or the presence of a ring on the stem, which is absent in most edible species.

For novice foragers, a step-by-step approach is essential. First, consult a field guide or app with high-resolution images. Second, examine the mushroom’s underside with a magnifying glass to compare gill or tube spacing and attachment. Third, perform a taste test only if absolutely certain—even a small nibble of a toxic species can be harmful. Finally, when in doubt, throw it out. No meal is worth risking organ damage or worse.

The takeaway is clear: toxic look-alikes exploit our reliance on familiar structures like tubes or gills. By combining meticulous observation, environmental context, and a healthy dose of skepticism, foragers can enjoy the bounty of edible mushrooms while avoiding their deadly mimics. Remember, the forest floor is a minefield of deception—tread carefully.

Are Bark Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging Practices

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all edible mushrooms have tubes or gills. Some, like chanterelles, have ridges and forks instead.

Tubes are the spore-bearing structures found on the underside of some mushrooms, like boletes. Edible mushrooms with tubes include porcini (bolete) and lion's mane.

Yes, edible gilled mushrooms, such as button mushrooms and shiitakes, have thin, blade-like structures (gills) under their caps where spores are produced.

No, tubes or gills alone are not enough to determine edibility. Always consult a field guide or expert, as some toxic mushrooms also have tubes or gills.

No, edible mushrooms typically have either tubes or gills, not both. Each structure is unique to specific mushroom families.