Gram-negative bacteria, characterized by their outer lipid membrane and thin peptidoglycan layer, are a diverse group of microorganisms known for their resistance to many antibiotics and environmental stresses. Unlike their gram-positive counterparts, which include spore-forming genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, gram-negative bacteria are generally not known to form spores. Sporulation is a survival mechanism that allows certain bacteria to withstand harsh conditions by producing highly resistant endospores. While some gram-negative bacteria, such as *Chromobacterium violaceum*, have been observed to produce cyst-like structures under specific conditions, these are not true spores and lack the same level of durability. Thus, the ability to form spores is predominantly a feature of gram-positive bacteria, with gram-negative species relying on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and efflux pumps, to survive adverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Gram-negative bacteria form spores? | No, most Gram-negative bacteria do not form spores. |

| Exceptions | A few rare exceptions exist, such as Adenosynbacter and Oceanibacillus, but these are not typical Gram-negative bacteria. |

| Spore formation in bacteria | Primarily observed in Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium). |

| Reason for lack of spore formation | Gram-negative bacteria lack the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation. |

| Survival strategies | Gram-negative bacteria use other methods like biofilm formation, persistence, and resistance mechanisms to survive harsh conditions. |

| Cell wall structure | Gram-negative bacteria have a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane, which does not support spore formation. |

| Relevance in medicine | Gram-negative bacteria are often associated with antibiotic resistance and hospital-acquired infections, but not spore-related diseases. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporulation in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are traditionally known for their outer membrane and thin peptidoglycan layer, but their ability to form spores has long been a subject of debate. While sporulation is a well-documented survival mechanism in Gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, Gram-negative species were historically considered non-sporulating. However, recent discoveries challenge this assumption, revealing that certain Gram-negative bacteria do indeed form spore-like structures under specific environmental stresses. These findings expand our understanding of bacterial resilience and have implications for fields ranging from medicine to biotechnology.

One notable example is *Chromobacterium violaceum*, a Gram-negative bacterium that produces spore-like structures under nutrient deprivation. These structures exhibit enhanced resistance to heat, desiccation, and antibiotics, mirroring the protective functions of spores in Gram-positive organisms. Another example is *Desulfotomaculum*, a sulfate-reducing bacterium that forms endospores despite its Gram-negative classification. These cases highlight the diversity of survival strategies within the bacterial kingdom and suggest that sporulation may be more widespread than previously thought.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria has significant implications for infection control and treatment. Spores are notoriously difficult to eradicate, as they can persist in hostile environments for extended periods. If Gram-negative pathogens like *Escherichia coli* or *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* were found to form spores, it could complicate efforts to sterilize medical equipment or treat infections. However, this knowledge also opens avenues for developing targeted therapies that disrupt spore formation or germination, potentially reducing the reliance on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

For researchers and clinicians, investigating sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria requires a multidisciplinary approach. Techniques such as electron microscopy, genetic sequencing, and stress-induction experiments can help identify spore-like structures and the genes involved in their formation. For instance, studies have shown that overexpression of certain sigma factors in *E. coli* can induce spore-like phenotypes, offering a starting point for further exploration. Practical tips include using nutrient-limited media to simulate stress conditions and employing spore stains like malachite green to visualize resistant structures.

In conclusion, while sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria remains a relatively niche area of study, its potential impact on science and medicine is profound. By reevaluating long-held assumptions and embracing new discoveries, researchers can uncover novel mechanisms of bacterial survival and develop innovative strategies to combat persistent infections. Whether in the lab or the clinic, this emerging field promises to reshape our understanding of microbial resilience.

Understanding Spore Prints: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Mechanisms of Spore Formation

Spore formation, a survival strategy mastered by certain bacteria, is a complex process that ensures their endurance in harsh conditions. While Gram-negative bacteria are not typically known for spore formation, understanding the mechanisms of this process in their Gram-positive counterparts provides valuable insights into bacterial resilience. The ability to form spores is a remarkable adaptation, allowing bacteria to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical stressors. This process involves a series of intricate cellular changes, culminating in the creation of a highly resistant spore.

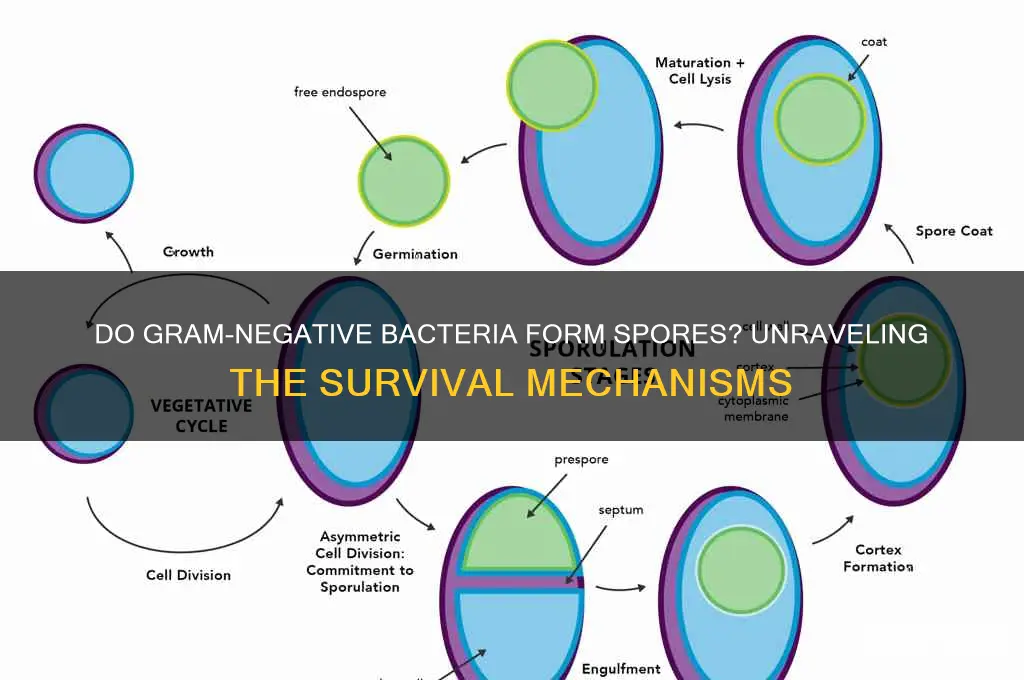

The Sporulation Journey: A Step-by-Step Transformation

Sporulation begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is precisely regulated, ensuring the correct positioning of the forespore within the mother cell. As the process progresses, the mother cell engulfs the forespore, creating a double-membrane structure. The space between these membranes becomes the site of intense activity, with the synthesis of spore-specific proteins and the modification of the cell wall. The mother cell then undergoes autolysis, releasing the mature spore, which is now equipped with a protective coat and a thickened, impermeable cell wall.

A Protective Coat: The Key to Spore Resilience

The spore coat is a critical component, providing a physical barrier against environmental stressors. It is composed of multiple layers of proteins, each with specific functions. Some proteins contribute to the coat's structural integrity, while others play a role in resisting heat, enzymes, or chemicals. For instance, the presence of dipicolinic acid, a calcium-chelating agent, is essential for heat resistance in spores. This unique chemical composition allows spores to remain viable for extended periods, even in the most adverse conditions.

Regulation and Timing: A Precise Dance

The decision to initiate sporulation is tightly regulated, ensuring it occurs only when necessary. This process is controlled by a network of genes and signaling molecules that respond to environmental cues. For example, the lack of nutrients or the presence of specific stressors can trigger the sporulation pathway. The timing of each step is crucial; premature or delayed sporulation can lead to non-viable spores. This precision is achieved through a series of checkpoints, where the cell verifies the completion of one stage before progressing to the next.

Practical Implications and Applications

Understanding spore formation has significant implications in various fields. In medicine, it helps explain the persistence of certain bacterial infections, as spores can remain dormant in the body, evading the immune system. In the food industry, spore-forming bacteria are a major concern, as they can survive standard cooking temperatures and cause food spoilage or foodborne illnesses. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can develop more effective sterilization techniques and preservation methods. For instance, specific spore-targeting antibiotics or improved autoclave protocols can be designed to ensure complete bacterial eradication.

In summary, while Gram-negative bacteria do not typically form spores, exploring the mechanisms of spore formation in other bacteria reveals a fascinating survival strategy. This process involves a series of carefully orchestrated cellular changes, resulting in a highly resistant spore. The practical applications of this knowledge are far-reaching, impacting fields from healthcare to food safety, and highlighting the importance of understanding bacterial resilience.

Extending Mushroom Spores Lifespan: Fridge Storage Tips and Duration

You may want to see also

Species Known to Sporulate

Gram-negative bacteria are primarily known for their outer lipid membrane, which distinguishes them from Gram-positive bacteria. While sporulation is a hallmark of certain Gram-positive species, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, it is less common among Gram-negative bacteria. However, exceptions exist, and understanding these species is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and environmental science. Among the Gram-negative bacteria known to sporulate, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* are not included, as they are Gram-positive. Instead, the focus shifts to rare but significant examples like *Desulfotomaculum* and *Sporomusa*, which challenge the conventional understanding of Gram-negative bacteria.

One notable example is *Desulfotomaculum*, a genus of sulfate-reducing bacteria found in diverse environments, including soil and aquatic sediments. These bacteria form spores under unfavorable conditions, such as nutrient depletion or oxygen exposure. Sporulation in *Desulfotomaculum* is a survival mechanism, allowing them to persist in harsh environments for extended periods. For researchers studying anaerobic ecosystems, understanding this process is essential, as it influences nutrient cycling and microbial community dynamics. Practical applications include bioremediation, where *Desulfotomaculum* spores can be used to degrade contaminants in oxygen-limited environments.

Another species of interest is *Sporomusa*, a Gram-negative bacterium capable of sporulation and known for its role in syntrophic metabolism. *Sporomusa* forms spores in response to environmental stressors, such as changes in pH or temperature. This ability is particularly relevant in industrial settings, where *Sporomusa* is used in bioenergy production through processes like hydrogen generation. For instance, in anaerobic digesters, *Sporomusa* spores can enhance system resilience by surviving transient unfavorable conditions and resuming metabolic activity when conditions improve. Engineers and biotechnologists can optimize bioreactor performance by accounting for *Sporomusa*’s sporulation behavior.

Comparatively, while *Desulfotomaculum* and *Sporomusa* are the most well-documented Gram-negative sporulating bacteria, other candidates like *Moorella* and *Carboxydothermus* are emerging in research. *Moorella*, for example, is a thermophilic bacterium that forms spores in high-temperature environments, such as hot springs. This makes it a candidate for studying extremophile biology and potential biotechnological applications in thermostable enzyme production. *Carboxydothermus*, on the other hand, sporulates in carbon-rich environments, offering insights into carbon sequestration and biofuel production. These examples highlight the diversity of Gram-negative sporulating bacteria and their untapped potential.

In practical terms, identifying and culturing Gram-negative sporulating bacteria requires specific techniques. For instance, *Desulfotomaculum* spores can be isolated using selective media containing sulfate and grown under anaerobic conditions. Researchers should maintain strict anaerobic environments using tools like anaerobic chambers or GasPak jars. For *Sporomusa*, syntrophic co-cultures with hydrogen-consuming partners are often necessary to stimulate growth and sporulation. Caution must be exercised when handling these bacteria, as their spores can survive extreme conditions and contaminate experiments if not properly inactivated. Heat treatment at 80°C for 20 minutes is a common method to destroy spores before disposal.

In conclusion, while Gram-negative bacteria are not typically associated with sporulation, species like *Desulfotomaculum*, *Sporomusa*, *Moorella*, and *Carboxydothermus* defy this generalization. Their ability to form spores under specific conditions offers insights into microbial survival strategies and opens avenues for biotechnological applications. By studying these exceptions, scientists can expand their understanding of bacterial resilience and harness their unique capabilities for practical purposes. Whether in environmental remediation, bioenergy production, or extremophile research, these sporulating Gram-negative bacteria represent a fascinating and underutilized resource.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Crafting Liquid Culture from Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.25

Environmental Triggers for Sporulation

Sporulation in bacteria is a survival mechanism triggered by harsh environmental conditions, but it is predominantly associated with Gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. Gram-negative bacteria, such as *Escherichia coli* and *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, generally do not form spores. However, understanding the environmental triggers for sporulation in spore-forming bacteria provides insights into the conditions that drive such survival strategies, even if Gram-negative bacteria lack this capability.

Environmental stressors act as critical triggers for sporulation in spore-forming bacteria. Nutrient depletion, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources, is a primary signal. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* initiates sporulation when amino acids and glucose become scarce, as detected by the Spo0A regulatory protein. This response ensures survival in nutrient-poor environments. Similarly, dehydration and high salinity can induce sporulation, as seen in soil-dwelling bacteria exposed to arid conditions. These triggers highlight the adaptive nature of sporulation in response to resource limitations.

Temperature fluctuations also play a significant role in sporulation. Extreme temperatures, both high and low, can prompt spore formation. For example, *Bacillus cereus* sporulates in response to heat stress, while *Bacillus psychrophilus* does so in cold environments. These temperature-driven responses are mediated by stress-responsive genes that activate sporulation pathways. Understanding these mechanisms underscores the importance of temperature as a universal environmental cue for survival strategies in bacteria.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to controlling bacterial growth in various settings. In food preservation, for instance, manipulating environmental conditions like nutrient availability and temperature can inhibit sporulation in contaminants. For example, storing food at low temperatures (below 4°C) slows bacterial metabolism and delays sporulation. Conversely, in biotechnology, inducing sporulation in controlled environments can enhance the production of bacterial spores for use in probiotics or vaccines.

While Gram-negative bacteria do not form spores, studying environmental triggers for sporulation in Gram-positive bacteria offers valuable lessons in microbial resilience. These triggers—nutrient depletion, dehydration, salinity, and temperature extremes—reveal how bacteria adapt to survive adverse conditions. By applying this knowledge, we can develop strategies to manage bacterial populations in both industrial and natural settings, ensuring safety and efficiency in processes ranging from food production to environmental remediation.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Differences from Gram-Positive Spores

Gram-negative bacteria are known for their distinct cell wall structure, but their ability to form spores is a topic of intrigue. Unlike their Gram-positive counterparts, Gram-negative bacteria generally do not produce spores as a survival mechanism. This fundamental difference raises questions about the resilience and adaptability of these two bacterial groups in harsh environments.

The Sporulation Process: A Gram-Positive Privilege

Sporulation, a complex process of spore formation, is predominantly observed in Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species. These bacteria, when faced with adverse conditions like nutrient depletion or extreme temperatures, can differentiate into highly resistant endospores. The spore's structure, characterized by a thick, protective coat and a dehydrated core, enables it to withstand extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and chemicals. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, can survive in spore form for decades, making it a significant concern in bioterrorism.

In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria lack this sporulation capability. Their cell wall structure, composed of an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides, provides a different kind of protection. This outer membrane acts as a barrier, preventing the entry of many antibiotics and toxic substances, but it does not offer the same level of resilience as a spore.

Mechanisms of Survival: Alternative Strategies

Without the ability to form spores, Gram-negative bacteria have evolved alternative strategies to ensure their survival. One such mechanism is the production of biofilms, which are communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced protective matrix. Biofilms provide a physical barrier against antibiotics and host immune responses, allowing bacteria to persist in hostile environments. For example, *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, a common Gram-negative pathogen, is known for its biofilm formation in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, making it challenging to eradicate.

Additionally, some Gram-negative bacteria can enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, where they remain metabolically active but cannot be detected by standard culturing methods. This state is induced by various stress factors and allows bacteria to persist in adverse conditions. Research suggests that VBNC bacteria may still pose a risk to human health, as they can revert to a culturable state under favorable conditions.

Implications for Treatment and Control

The absence of spore formation in Gram-negative bacteria has significant implications for infection control and treatment strategies. Since spores are not a concern, disinfection methods can focus on targeting the vegetative cells and their biofilms. This often involves the use of specific antibiotics, such as beta-lactams or fluoroquinolones, which can penetrate the Gram-negative cell wall. However, the emergence of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, like carbapenem-resistant *Enterobacteriaceae* (CRE), poses a growing challenge, requiring the development of novel antibiotics and treatment approaches.

In summary, while Gram-positive bacteria utilize sporulation as a key survival strategy, Gram-negative bacteria have evolved distinct mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and the VBNC state, to endure harsh conditions. Understanding these differences is crucial for developing effective control measures and treatments tailored to each bacterial group's unique characteristics. This knowledge is particularly relevant in healthcare settings, where preventing and managing infections caused by these bacteria is essential for patient safety.

Understanding Mold Spores Lifespan: How Long Do They Survive?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, gram-negative bacteria do not typically form spores. Sporulation is a characteristic primarily associated with certain gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*.

Yes, there are rare exceptions. Some gram-negative bacteria, like *Xanthomonas* and *Achromobacter*, have been observed to produce spore-like structures, but these are not true endospores and are less resistant to harsh conditions.

Gram-negative bacteria lack the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation. Their cell wall structure and composition differ from gram-positive bacteria, making spore formation energetically and structurally unfavorable.

Gram-negative bacteria use alternative survival strategies, such as forming biofilms, producing protective extracellular polymers, or entering a dormant state through mechanisms like persister cells, to withstand adverse environments.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)