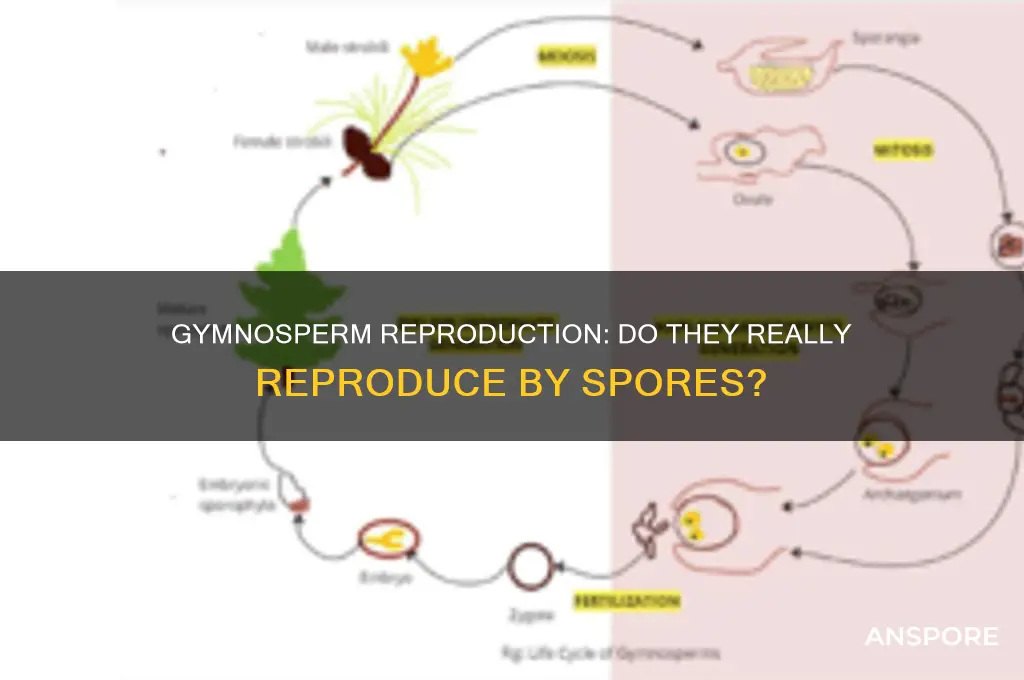

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, primarily reproduce through seeds rather than spores. However, they do produce spores as part of their life cycle, specifically during the alternation of generations. In gymnosperms, the sporophyte (the dominant, diploid phase) produces two types of spores: microspores, which develop into pollen grains, and megaspores, which give rise to the female gametophyte. These spores are crucial for sexual reproduction, as they facilitate the formation of male and female gametes. While gymnosperms are not classified as spore-reproducing plants in the same way as ferns or mosses, their reliance on spores for part of their reproductive process highlights the complexity and diversity of plant life cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Gymnosperms do not reproduce by spores. |

| Reproductive Structures | They produce seeds that are not enclosed in an ovary. |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte dominant, gametophyte reduced). |

| Sporophyte Phase | Dominant and long-lived (e.g., trees like pines, spruces). |

| Gametophyte Phase | Reduced and dependent on the sporophyte (e.g., pollen grains, archegonia). |

| Seed Formation | Seeds develop from ovules after fertilization, exposed on cones or scales. |

| Spore Production | Produce spores (microspores and megaspores) for gametophyte development, but not for reproduction. |

| Pollination | Wind-pollinated, with pollen grains transferring male gametes to female cones. |

| Examples | Conifers (pines, firs), cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes. |

| Distinction from Pteridophytes | Unlike ferns and mosses, gymnosperms do not rely on spores for reproduction. |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation in Gymnosperms: Gymnosperms produce spores in cones, which develop into gametophytes

- Male vs. Female Spores: Microspores (male) and megaspores (female) are produced in separate cones

- Pollination Process: Wind carries male spores to female cones for fertilization in gymnosperms

- Gametophyte Development: Spores germinate into tiny gametophytes, producing gametes for reproduction

- Seed Formation: Fertilized female gametophytes develop into seeds, completing the gymnosperm life cycle

Spore Formation in Gymnosperms: Gymnosperms produce spores in cones, which develop into gametophytes

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants including conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, employ a unique reproductive strategy centered on spore formation within cones. Unlike angiosperms, which enclose their seeds in ovaries, gymnosperms expose their seeds on the surface of cones, a trait reflected in their name, derived from the Greek *gymnos* (naked) and *sperma* (seed). This process begins with the production of spores, which are housed in specialized structures called cones. These spores are not merely dormant cells but the precursors to gametophytes, the diminutive plants that facilitate sexual reproduction.

The lifecycle of gymnosperms is heterosporous, meaning they produce two types of spores: microspores and megaspores. Microspores, smaller and more numerous, develop into male gametophytes, while megaspores, larger and fewer, give rise to female gametophytes. These spores are formed within microsporangia and megasporangia, respectively, which are located in the male and female cones. The male cones, typically smaller and more transient, release microspores that are carried by wind to female cones. Female cones, larger and more durable, contain ovules where megaspores develop. This division of labor ensures efficient pollination and fertilization, even in the absence of animals or water as vectors.

Once spores are dispersed, they germinate into gametophytes. The male gametophyte, or pollen grain, is a simple structure consisting of a few cells, one of which becomes the sperm. It is transported to the female cone via wind pollination. The female gametophyte, housed within the ovule, is more complex, developing archegonia that produce egg cells. Fertilization occurs when the sperm from the male gametophyte reaches the egg, resulting in the formation of a zygote, which develops into an embryo. This embryo, along with stored nutrients, becomes the seed, ready to grow into a new plant.

Understanding spore formation in gymnosperms offers practical insights for horticulture and conservation. For instance, conifer growers can optimize seed production by ensuring adequate wind exposure for pollination. Additionally, knowledge of spore development aids in the preservation of endangered species like cycads, whose reproductive cycles are slow and vulnerable to disruption. By studying these processes, scientists and enthusiasts alike can contribute to the sustainability of these ancient plants, which play vital roles in ecosystems worldwide.

In summary, spore formation in gymnosperms is a fascinating interplay of structure and function, culminating in the production of gametophytes that drive sexual reproduction. From the heterosporous lifecycle to the role of cones in spore protection and dispersal, this process highlights the adaptability and resilience of gymnosperms. Whether for scientific inquiry or practical application, exploring this mechanism deepens our appreciation for these plants and their enduring significance in the natural world.

Can Antibiotics Kill Spores? Unraveling the Science Behind Resistance

You may want to see also

Male vs. Female Spores: Microspores (male) and megaspores (female) are produced in separate cones

Gymnosperms, such as conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, rely on a unique reproductive strategy centered around the production of spores. Unlike angiosperms, which enclose their seeds within ovaries, gymnosperms produce their spores in distinct structures called cones. These cones are not merely protective casings but specialized organs that differentiate into male and female forms, each with a specific role in reproduction. The male cones produce microspores, while the female cones produce megaspores, setting the stage for a fascinating interplay of sexual reproduction in these plants.

Consider the process of microspore production in male cones. Each microspore is a tiny, haploid cell that develops into a pollen grain. These grains are lightweight and often wind-dispersed, allowing them to travel significant distances to reach female cones. For example, pine trees release billions of pollen grains annually, ensuring that at least some will successfully fertilize megaspores. This strategy, while inefficient in terms of resource use, maximizes the chances of cross-pollination, promoting genetic diversity. In contrast, megaspores, produced in female cones, are larger and remain within the cone. One megaspore develops into a female gametophyte, which houses the egg cell awaiting fertilization.

The separation of microspores and megaspores into distinct cones is a critical adaptation for gymnosperms. This division ensures that male and female reproductive structures mature independently, reducing the risk of self-fertilization. For instance, in species like spruce and fir, male cones often appear on lower branches, while female cones develop higher up, further minimizing the likelihood of self-pollination. This spatial separation, combined with the timing of pollen release and cone receptivity, enhances the efficiency of outcrossing, a key advantage in heterogeneous environments.

Practical observations of gymnosperm reproduction reveal intriguing details. For hobbyists or educators studying these plants, examining cones under a magnifying glass can provide insights into their reproductive anatomy. Male cones, typically smaller and more numerous, shed after releasing pollen, while female cones may persist longer, eventually developing into seed-bearing structures. For example, the female cones of pine trees can take up to two years to mature, highlighting the extended timeline of gymnosperm reproduction. Understanding these differences allows for better identification and appreciation of these plants in their natural habitats.

In conclusion, the production of microspores and megaspores in separate cones is a cornerstone of gymnosperm reproduction. This system not only facilitates efficient pollination but also promotes genetic diversity, a vital trait for long-term survival. By studying these mechanisms, we gain a deeper understanding of plant evolution and the strategies organisms employ to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Whether for academic research or personal curiosity, exploring the intricacies of gymnosperm spores offers a window into the remarkable complexity of the natural world.

Hyphae, Spores, and Molds: Understanding Their Interconnected Fungal Roles

You may want to see also

Pollination Process: Wind carries male spores to female cones for fertilization in gymnosperms

Gymnosperms, such as pines and spruces, rely on wind pollination to transport male spores, or pollen grains, to female cones for fertilization. This process, known as anemophily, is highly efficient in open environments where wind currents are consistent. Male cones produce microspores in large quantities, which are lightweight and easily carried by air currents. Female cones, positioned higher on the tree, have exposed ovules ready to receive the pollen. This spatial arrangement maximizes the chances of successful pollination, ensuring the continuation of the species.

The mechanism of wind pollination in gymnosperms is a marvel of adaptation. Unlike angiosperms, which often attract pollinators with colorful flowers and nectar, gymnosperms invest in producing vast amounts of pollen to increase the likelihood of reaching a female cone. For example, a single pine tree can release millions of pollen grains in a single season. This strategy compensates for the randomness of wind dispersal, as only a fraction of the pollen will land on a receptive ovule. The success of this method lies in its simplicity and scalability, making it ideal for species that dominate large, uninterrupted habitats like forests.

To observe this process, one can examine the structure of gymnosperm cones during the spring season. Male cones, typically smaller and more numerous, release a cloud of yellow pollen when mature. Female cones, often larger and located higher on the tree, have open scales that allow pollen to enter. A practical tip for enthusiasts is to place a white sheet under a conifer during peak pollination to collect and observe the pollen. This simple experiment highlights the sheer volume of pollen produced and the reliance on wind for dispersal.

Despite its effectiveness, wind pollination in gymnosperms is not without challenges. Pollen grains must travel significant distances, often against environmental obstacles like rain or dense foliage. Additionally, the lack of specificity in pollen delivery means that much of it lands in unsuitable locations. However, the evolutionary success of gymnosperms demonstrates that this method, though inefficient in terms of pollen usage, is highly effective in ensuring genetic diversity and species survival. For gardeners or foresters, understanding this process can inform planting strategies, such as spacing trees to optimize wind flow and pollen dispersal.

In conclusion, the pollination process in gymnosperms is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By harnessing wind to carry male spores to female cones, these plants have thrived in diverse ecosystems for millions of years. This method, while seemingly wasteful, ensures widespread fertilization and adaptability. For those studying or working with gymnosperms, recognizing the role of wind in their reproductive cycle provides valuable insights into their ecology and management. Whether in a forest or a garden, the dance of pollen on the breeze is a silent yet vital force in the life of these ancient plants.

Do Angiosperms Reproduce by Spores? Unraveling Plant Reproduction Myths

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gametophyte Development: Spores germinate into tiny gametophytes, producing gametes for reproduction

Gymnosperms, unlike angiosperms, do not produce flowers or fruits, but they do share a fundamental reproductive strategy rooted in spore-based alternation of generations. This process begins with the germination of spores into gametophytes, which are diminutive, yet crucial, structures responsible for gamete production. These gametophytes are the linchpins of gymnosperm reproduction, bridging the gap between the sporophyte (the dominant, visible plant) and the next generation. Understanding their development offers insight into the evolutionary continuity between ancient plant lineages and modern flora.

The lifecycle of gymnosperms is a delicate dance between sporophyte and gametophyte phases. Spores, produced in cones or analogous structures, are dispersed and, upon finding suitable conditions, germinate into gametophytes. Male gametophytes, or microgametophytes, develop within pollen grains and are transported by wind to female cones. Female gametophytes, or megagametophytes, form within ovules and provide the environment for fertilization. This division of labor ensures genetic diversity while maintaining the structural simplicity characteristic of gymnosperms.

Consider the male gametophyte’s journey: after landing on a female cone, the pollen grain germinates, producing a pollen tube that grows toward the ovule. This process, known as siphonogamy, is a hallmark of seed plants and ensures successful delivery of sperm cells. The female gametophyte, meanwhile, nurtures the egg cell and provides nutrients for early embryo development. This symbiotic relationship between male and female gametophytes underscores the efficiency of gymnosperm reproduction, even in the absence of flowers.

Practical observation of gametophyte development can be facilitated by examining pine or spruce cones under a microscope. Male cones, typically smaller and more numerous, release pollen grains that can be collected and observed for germination. Female cones, larger and more robust, contain ovules where megagametophytes develop. By dissecting these structures, one can witness the intricate interplay between spores, gametophytes, and the eventual formation of seeds. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also highlights the resilience of gymnosperms in diverse ecosystems.

In conclusion, gametophyte development in gymnosperms is a testament to the elegance of nature’s reproductive strategies. From spore germination to gamete production, each step is finely tuned to ensure the survival and propagation of these ancient plants. By studying this process, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also appreciation for the enduring legacy of gymnosperms in the plant kingdom.

Can Carbon Filters Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Seed Formation: Fertilized female gametophytes develop into seeds, completing the gymnosperm life cycle

Gymnosperms, unlike angiosperms, do not produce flowers or fruits, yet their reproductive strategy is a marvel of efficiency and adaptation. Central to this process is the development of seeds from fertilized female gametophytes, a mechanism that ensures the continuation of species in diverse environments. This seed formation is a critical phase in the gymnosperm life cycle, marking the transition from a spore-dependent stage to a seed-producing one.

The Journey from Gametophyte to Seed

Following pollination, the male gametophyte delivers sperm cells to the female gametophyte, housed within the ovule. Fertilization occurs, resulting in the formation of a zygote, which develops into the embryo. Simultaneously, the female gametophyte nurtures this embryo, providing essential nutrients and protection. Over time, the ovule matures into a seed, encapsulating the embryo, stored food reserves, and a protective seed coat. This transformation is a testament to the gymnosperm’s ability to thrive without the enclosure of an ovary or fruit, as seen in angiosperms.

Environmental and Developmental Factors

Seed formation in gymnosperms is influenced by both genetic and environmental cues. Temperature, light, and water availability play pivotal roles in regulating the timing and success of fertilization and seed maturation. For instance, conifers often require specific chilling periods to initiate reproductive processes. Additionally, the longevity of female gametophytes—sometimes persisting for years—allows gymnosperms to synchronize seed production with favorable conditions, enhancing survival rates.

Practical Implications and Applications

Understanding seed formation in gymnosperms has significant implications for forestry, conservation, and agriculture. For example, knowing the optimal conditions for fertilization can improve reforestation efforts, particularly in regions affected by climate change. Horticulturists can also leverage this knowledge to cultivate gymnosperms like pines and spruces more effectively. Practical tips include monitoring soil moisture during pollination seasons and providing shade for young seedlings to mimic natural habitats.

Comparative Advantage Over Spore Reproduction

While gymnosperms begin their life cycle with spore production (via sporophytes and gametophytes), the shift to seed formation represents a critical evolutionary advancement. Seeds offer greater protection and nutrient storage compared to spores, enabling gymnosperms to colonize a wider range of habitats. This adaptation reduces reliance on water for reproduction, a limitation faced by spore-dependent plants like ferns. By completing their life cycle with seeds, gymnosperms ensure genetic continuity and resilience in challenging environments.

Predicting Spore's Defeat: Analyzing Potential Round Losses in the Match

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, gymnosperms reproduce by spores, but only during their alternation of generations life cycle. They produce both microspores (male) and megaspores (female) in cones.

Gymnosperms use spores to initiate the gametophyte generation. Microspores develop into male gametophytes (pollen grains), while megaspores develop into female gametophytes inside ovules.

No, spores are part of the sexual reproduction process in gymnosperms, but they also rely on seeds for their primary method of reproduction, which distinguishes them from ferns and other spore-dependent plants.

Spores in gymnosperms give rise to gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and egg). Fertilization of these gametes results in the formation of seeds, which are then dispersed for new plant growth.