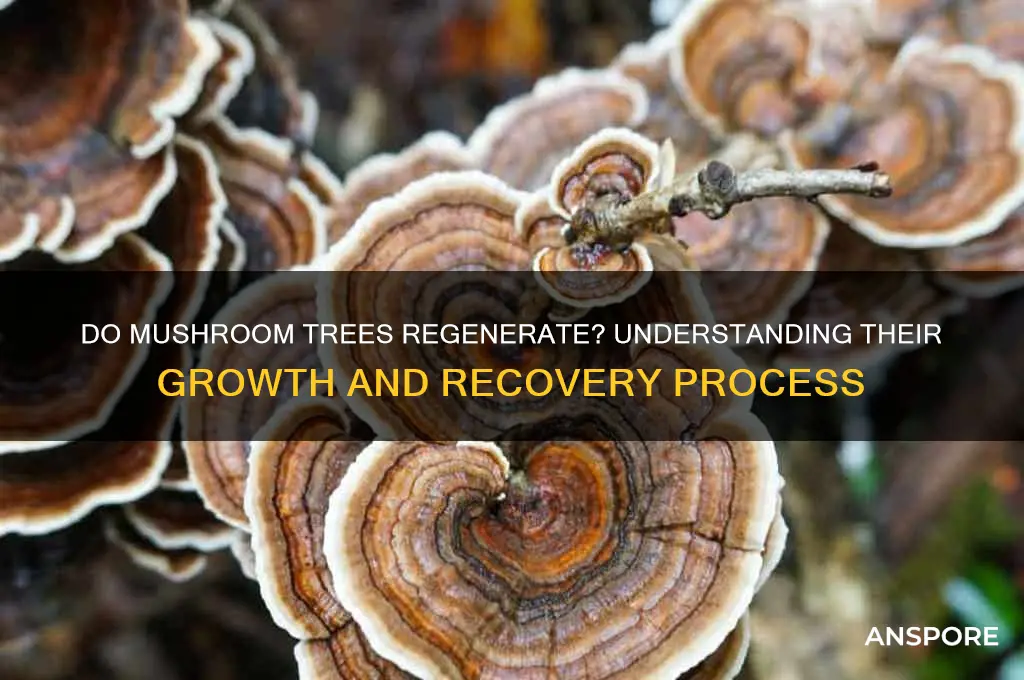

Mushroom trees, more accurately referred to as fungal mycelium networks, are not trees in the traditional sense but rather complex underground systems of fungi that support various ecosystems. When discussing whether these mushroom trees grow back, it’s important to clarify that mushrooms themselves are the fruiting bodies of fungi, while the mycelium is the root-like structure that persists beneath the surface. If a mushroom is harvested or damaged, the mycelium can often regenerate and produce new mushrooms under favorable conditions, such as adequate moisture, nutrients, and temperature. However, repeated disturbance or environmental stress can weaken the mycelium, potentially hindering its ability to recover. Understanding this regenerative capacity is crucial for sustainable foraging and conservation efforts, as it highlights the delicate balance between human interaction and the health of fungal ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Regeneration Ability | Mushroom trees, also known as fungal trees or mycelium-based structures, do not grow back in the traditional sense like plants. However, the mycelium network (the vegetative part of a fungus) can regenerate under favorable conditions. |

| Mycelium Survival | The mycelium can survive in the soil for extended periods, even after the visible mushroom or fungal structure has decayed. |

| Environmental Factors | Regeneration depends on factors like moisture, temperature, nutrient availability, and lack of disturbance in the soil. |

| Fruiting Bodies | Mushroom fruiting bodies (the visible part) do not regrow from the same spot once harvested or decayed, but new fruiting bodies can emerge from the same mycelium network elsewhere. |

| Cultivation Practices | In controlled environments, mycelium can be cultivated to produce new mushroom fruiting bodies repeatedly, given proper care and substrate. |

| Natural Decay | In nature, mushroom trees or fruiting bodies decompose, returning nutrients to the soil, but the mycelium may persist and produce new growth under suitable conditions. |

| Species Variation | Some fungal species are more resilient and likely to regenerate than others, depending on their biology and habitat. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushroom tree life cycle

The life cycle of a mushroom tree, more accurately referred to as a fungus that forms mycorrhizal associations with trees, is a fascinating and complex process. Unlike trees, mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, and their life cycle is closely tied to the health and growth of the associated tree. The question of whether mushroom trees grow back is rooted in understanding this symbiotic relationship and the fungal life cycle. Fungi, including those that produce mushrooms, grow through a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which can persist in the soil for many years.

The life cycle begins with spore germination. When conditions are favorable—typically involving adequate moisture, temperature, and organic matter—spores released from mature mushrooms land on the soil and germinate. These spores develop into hyphae, the individual filaments that collectively form the mycelium. The mycelium then expands through the soil, seeking nutrients and, in the case of mycorrhizal fungi, the roots of trees. Once the mycelium encounters a tree root, it forms a mutualistic relationship where the fungus helps the tree absorb water and nutrients, particularly phosphorus, while the tree provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

As the mycelium network grows and strengthens, it may eventually produce mushrooms under the right conditions, such as sufficient moisture and warmth. These mushrooms are the reproductive structures of the fungus, releasing spores to start the cycle anew. The mushrooms themselves are ephemeral, typically lasting only a few days to weeks, but the underlying mycelium can remain viable for years or even decades. This persistence is key to the question of whether mushroom trees grow back, as the mycelium can regenerate mushrooms seasonally or after disturbances.

Disturbances, such as harvesting mushrooms or environmental changes, do not necessarily kill the fungus. The mycelium can repair itself and continue to grow, often producing new mushrooms in subsequent seasons. However, severe damage to the mycelium or the associated tree can disrupt this cycle. For example, if the tree dies or the soil conditions become unfavorable, the fungus may decline or relocate. Therefore, while mushrooms may reappear year after year, their growth depends on the health of the mycelium and its tree partner.

In summary, the life cycle of a mushroom tree involves spore germination, mycelium growth, mycorrhizal formation with a tree, and mushroom production. The mycelium’s ability to persist and regenerate ensures that mushrooms can grow back under suitable conditions. However, this process is contingent on the continued health of both the fungus and the tree. Understanding this cycle highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems and the resilience of fungal networks.

Mastering Baby Bella Mushroom Cultivation: Simple Steps for Abundant Harvests

You may want to see also

Regeneration after harvesting

Mushroom trees, more accurately referred to as fungal mycelium networks associated with trees, play a crucial role in forest ecosystems. When considering the regeneration of these networks after harvesting, it’s essential to understand that mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, while the mycelium—the underground network—is the primary organism. Unlike trees, which regrow from stumps or seeds, fungal mycelium regenerates through its resilient network. After harvesting mushrooms, the mycelium often remains intact, provided the substrate (such as wood or soil) is undisturbed. This network can continue to grow and produce new mushrooms under favorable conditions, such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrients.

To promote regeneration after harvesting, maintaining the substrate’s integrity is key. For wood-loving fungi, leaving some mushrooms to release spores can help replenish the mycelium. In agricultural settings, such as mushroom farms, ensuring the growing medium (e.g., straw or sawdust) remains uncontaminated and nutrient-rich supports ongoing mycelium growth. For forest ecosystems, avoiding soil compaction and preserving organic matter fosters a healthy environment for mycelium regeneration. Additionally, managing moisture levels is critical, as fungi require specific humidity to thrive and produce new fruiting bodies.

In natural settings, the regenerative capacity of fungal mycelium is remarkable. Even after disturbances like harvesting, the network can repair itself and resume growth. However, repeated or aggressive harvesting without allowing recovery time can weaken the mycelium. Sustainable practices, such as rotational harvesting or leaving certain areas untouched, ensure long-term regeneration. For mycorrhizal networks, protecting the associated trees from stress or disease is equally important, as the health of the fungus is directly tied to its host.

Finally, understanding the lifecycle of fungi is vital for effective regeneration management. Unlike plants, fungi do not rely on seeds or visible structures for regrowth. Instead, their resilience lies in the mycelium’s ability to persist and adapt. By respecting this natural process and adopting practices that minimize disruption, both wild and cultivated mushroom populations can regenerate successfully after harvesting. This approach not only supports fungal ecosystems but also ensures a sustainable yield for harvesters.

Mysterious Fairy Rings: Unveiling Why Mushrooms Grow in Circular Patterns

You may want to see also

Factors affecting regrowth

Mushroom trees, more accurately referred to as fungi associated with trees or mycorrhizal networks, do not "grow back" in the same way a tree does after being cut down. Instead, the regrowth of mushrooms depends on the health and vitality of the fungal mycelium, the underground network of thread-like structures that support mushroom production. Several factors influence whether and how quickly mushrooms will reappear after harvesting or disturbance. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone interested in sustainable foraging or cultivating mushrooms.

Substrate and Environmental Conditions

The primary factor affecting regrowth is the condition of the substrate, which is the material the mycelium colonizes, often wood, soil, or decaying organic matter. If the substrate remains intact and nutrient-rich, the mycelium can continue to thrive and produce mushrooms. For example, in a forest, a fallen log colonized by oyster mushrooms will continue to fruit as long as the wood is not fully decomposed. However, if the substrate is damaged, removed, or depleted of nutrients, regrowth will be hindered. Environmental conditions such as moisture, temperature, and humidity also play a critical role. Mushrooms require specific conditions to fruit, and deviations from these optimal ranges can delay or prevent regrowth.

Mycelium Health and Disturbance

The health of the mycelium is another critical factor. Overharvesting or improper harvesting techniques can damage the mycelium, reducing its ability to recover and produce new mushrooms. For instance, pulling mushrooms out of the ground instead of cutting them can disrupt the mycelium. Additionally, physical disturbances like tilling soil or heavy foot traffic can destroy the delicate network, preventing regrowth. In contrast, leaving the base of the mushroom intact and minimizing disturbance to the surrounding area can encourage the mycelium to repair itself and fruit again.

Competition and Pests

Competition from other organisms can also affect regrowth. In natural settings, mushrooms often compete with bacteria, molds, and other fungi for resources. If competing organisms outpace the mycelium, mushroom production may decline. Pests such as slugs, insects, or rodents can consume mushrooms before they mature or damage the mycelium directly. Managing these competitors and pests through natural methods, such as introducing predators or creating barriers, can support regrowth.

Seasonality and Life Cycle

Seasonality plays a significant role in mushroom regrowth. Most mushrooms have specific fruiting seasons tied to environmental cues like temperature, rainfall, and daylight. For example, morel mushrooms typically fruit in spring, while chanterelles are more common in late summer and fall. Understanding these cycles is essential for predicting regrowth. Additionally, some mushrooms have annual life cycles, fruiting only once before the mycelium dies, while others are perennial, fruiting repeatedly over several years. Knowing the life cycle of the specific mushroom species is key to managing expectations for regrowth.

Human Intervention and Cultivation

Human intervention can either support or hinder regrowth. In cultivation settings, factors like controlled environments, proper substrate preparation, and mycelium care can enhance regrowth. Techniques such as inoculating logs or beds with mycelium can establish new fungal networks, ensuring consistent mushroom production. However, in wild settings, activities like deforestation, pollution, or climate change can disrupt natural habitats, making regrowth difficult or impossible. Sustainable practices, such as leaving some mushrooms to release spores and avoiding overharvesting, can help maintain healthy mycelium populations and support regrowth in natural ecosystems.

Master Shiitake Log Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Growing Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sustainable mushroom tree farming

Mushroom trees, often referred to as fungi-bearing trees or mycorrhizal trees, are not actually trees that grow mushrooms directly from their trunks or branches. Instead, these trees form symbiotic relationships with certain fungi, which grow mushrooms at their base or in the surrounding soil. The question of whether mushroom trees grow back is closely tied to the sustainability of both the tree and the fungal species involved. Sustainable mushroom tree farming focuses on maintaining this delicate balance while ensuring long-term productivity. By adopting practices that support both the tree and the fungi, farmers can create a regenerative system where both organisms thrive and continue to produce mushrooms over time.

One key aspect of sustainable mushroom tree farming is selecting the right tree species and fungal partners. Trees like oak, beech, and birch are commonly associated with mycorrhizal fungi that produce edible mushrooms such as porcini, chanterelles, and truffles. Planting these tree species in suitable environments ensures they grow healthily, providing a stable habitat for the fungi. Additionally, inoculating the soil with specific fungal spores during planting can establish a strong symbiotic relationship early on. This practice not only enhances mushroom production but also improves the tree’s nutrient uptake and resilience to environmental stressors.

Proper land management is another critical component of sustainability in mushroom tree farming. Avoiding overharvesting of mushrooms is essential, as it allows the fungal mycelium to recover and continue fruiting. Rotating harvest areas and leaving some mushrooms to release spores can help maintain a healthy fungal population. Furthermore, minimizing soil disturbance and avoiding the use of chemical fertilizers or pesticides protects the mycorrhizal network. Instead, organic matter such as wood chips or leaf litter can be added to the soil to support both the trees and the fungi.

Water management and climate considerations also play a significant role in sustainable mushroom tree farming. Mycorrhizal fungi thrive in well-drained, moist soil, so irrigation systems should be designed to mimic natural rainfall patterns. Mulching around the base of the trees can help retain soil moisture and regulate temperature, creating an ideal environment for both the trees and the fungi. In regions with varying climates, selecting tree and fungal species adapted to local conditions ensures the system remains productive year after year.

Finally, long-term planning and monitoring are essential for the success of sustainable mushroom tree farming. Regularly assessing the health of both the trees and the fungal populations allows farmers to address issues early, such as disease or nutrient deficiencies. Pruning trees to maintain their structure and removing competing vegetation can also support their growth and, by extension, mushroom production. By viewing the farm as an interconnected ecosystem, farmers can ensure that mushroom trees continue to grow back and produce mushrooms for generations, embodying the principles of sustainability.

Can Blue Oyster Mushrooms Thrive on Living Sugar Maple Trees?

You may want to see also

Species-specific regrowth rates

Mushroom trees, more accurately referred to as fungi associated with trees or mycorrhizal networks, exhibit species-specific regrowth rates that depend on the type of fungus and its ecological role. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), which often grow on decaying wood, can regrow rapidly under favorable conditions. These fungi are saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead organic matter. If the substrate (typically a fallen tree or log) remains moist and nutrient-rich, oyster mushrooms can fruit multiple times in a single growing season, with regrowth occurring within weeks after harvesting or natural decay. However, their ability to regrow depends on the continued availability of suitable wood and environmental conditions.

In contrast, morel mushrooms (Morchella spp.), which are highly prized for their culinary value, have a more complex regrowth pattern. Morels form symbiotic relationships with trees, particularly in disturbed soils or recently burned areas. Their regrowth is closely tied to specific environmental triggers, such as soil temperature, moisture, and the presence of compatible tree species. While morels can reappear annually in the same location, their regrowth is not guaranteed and can take months or even years, depending on conditions. Efforts to cultivate morels commercially have highlighted their sensitivity to environmental factors, making their regrowth rates highly species-specific and unpredictable.

Chanterelle mushrooms (Cantharellus cibarius) are another example of fungi with distinct regrowth characteristics. These mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic relationships with tree roots, particularly conifers and hardwoods. Their regrowth is slower compared to saprotrophic mushrooms, as it relies on the health and growth of the host tree. Chanterelles typically fruit seasonally, often in late summer and fall, and their regrowth can take several months to a year. Disturbing the soil or damaging the mycorrhizal network can significantly hinder their ability to regrow, underscoring the importance of species-specific ecological considerations.

Lion's Mane mushrooms (Hericium erinaceus) are unique in their regrowth behavior. These saprotrophic fungi grow on hardwood trees, particularly beech and oak, and are known for their ability to regrow on the same log multiple times. However, their regrowth rate is influenced by the log's decomposition stage and environmental conditions. Lion's Mane can take several weeks to months to regrow, with optimal conditions including cool temperatures and high humidity. Unlike some other species, they are less likely to regrow if the substrate is exhausted of nutrients, making substrate management critical for repeated fruiting.

Finally, shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) are cultivated on logs or sawdust blocks and have well-documented regrowth rates. These wood-decay fungi can fruit multiple times over 2-4 years on the same log, with regrowth intervals ranging from 3 to 12 months, depending on environmental conditions and substrate quality. Commercial growers often soak the logs to stimulate fruiting, demonstrating how species-specific management practices can enhance regrowth. Shiitake's ability to regrow consistently makes them a popular choice for both hobbyists and commercial cultivators, though their regrowth is still contingent on proper care and species-specific requirements.

Understanding these species-specific regrowth rates is essential for sustainable harvesting and cultivation. Each fungus has unique ecological needs, and factors such as substrate type, environmental conditions, and symbiotic relationships play critical roles in determining how and when they regrow. By tailoring practices to the specific requirements of each species, individuals can promote healthier fungal ecosystems and ensure the long-term viability of mushroom regrowth.

Are Mushroom Grow Kits Legal in Virginia? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom trees, or more accurately, fungi that grow on trees (like bracket fungi), do not regrow in the same way as plants. Once the fruiting body (mushroom) is harvested, it does not grow back, but the mycelium (root-like structure) may produce new mushrooms under suitable conditions.

There is no regrowth of the harvested mushroom itself, but new mushrooms may emerge from the same mycelium in weeks to months, depending on environmental factors like moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability.

Mushroom trees are not plants and cannot be replanted. However, you can cultivate new mushrooms by transferring the mycelium to a suitable substrate, such as wood or soil, under controlled conditions.

Cutting or harvesting a mushroom does not harm the mycelium, which can continue to produce new mushrooms. However, damaging the substrate (e.g., the tree it grows on) could affect the mycelium's ability to thrive.

While individual mushrooms do not regrow, the mycelium can produce new mushrooms repeatedly, making them a potentially renewable resource if managed sustainably and if the substrate remains healthy.