Mushrooms, as fungi, play a crucial role in ecosystems by acting as decomposers and recyclers of nutrients. Unlike plants, which convert inorganic molecules like carbon dioxide and water into organic molecules through photosynthesis, mushrooms primarily obtain their nutrients by breaking down organic matter. However, certain fungi, including some mushrooms, form symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizae) or engage in processes like chemoautotrophy, where they can indirectly contribute to the conversion of inorganic molecules into organic compounds. Additionally, some fungi use enzymes to solubilize minerals, making inorganic nutrients more accessible for absorption. While mushrooms themselves do not directly convert inorganic molecules into organic ones like plants do, their ecological functions and associations with other organisms highlight their indirect role in nutrient cycling and organic matter formation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process | Mushrooms, like other fungi, can convert inorganic molecules into organic molecules through a process called biological fixation or assimilation. |

| Key Mechanism | They primarily achieve this via enzymatic reactions, particularly through enzymes like nitrate reductase and sulfate reductase, which reduce inorganic compounds to organic forms. |

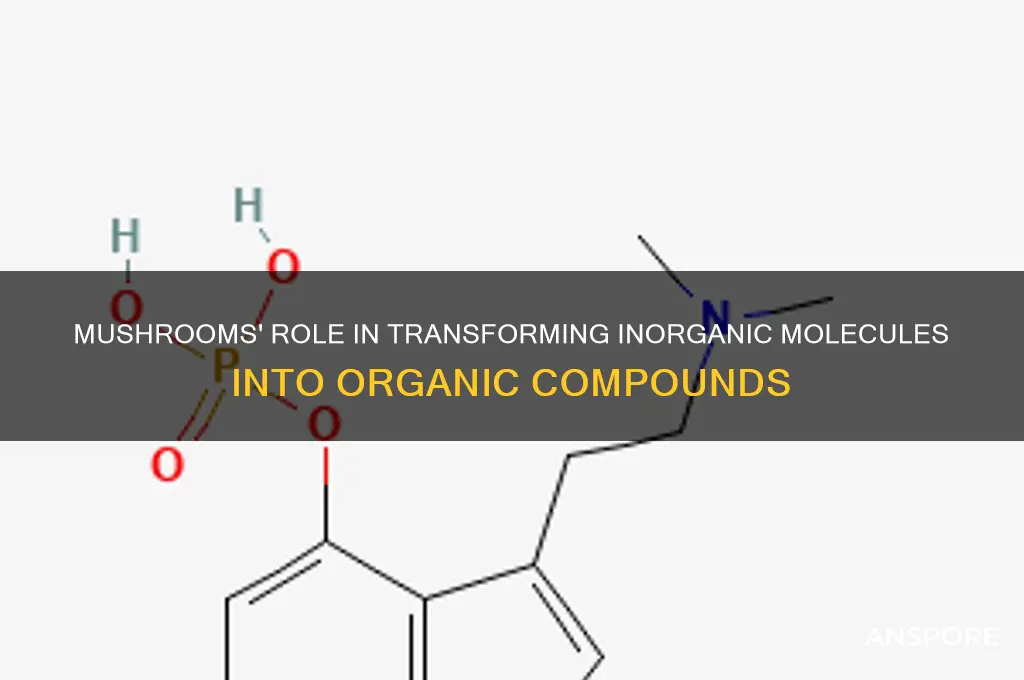

| Inorganic Molecules Converted | Nitrates (NO₃⁻) → Amino acids (e.g., glutamine), Sulfates (SO₄²⁻) → Sulfur-containing amino acids (e.g., cysteine), Phosphates (PO₄³⁻) → Phospholipids and nucleic acids. |

| Energy Source | Mushrooms use energy from decomposing organic matter or symbiotic relationships (e.g., mycorrhizal associations with plants) to drive these conversions. |

| Role in Ecosystems | Essential for nutrient cycling, especially in breaking down complex organic materials and releasing inorganic nutrients back into the soil. |

| Examples of Fungi | Saprotrophic mushrooms (e.g., Agaricus bisporus), mycorrhizal fungi (e.g., Amanita species), and lichens (symbiotic fungi with algae/cyanobacteria). |

| Limitations | Mushrooms cannot fix atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) directly, unlike some bacteria; they rely on already available inorganic forms like nitrates. |

| Environmental Impact | Contribute to soil fertility by converting inorganic compounds into forms usable by plants and other organisms. |

| Research Status | Well-documented in mycology and ecology, with ongoing studies on optimizing fungal processes for sustainable agriculture and bioremediation. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mycorrhizal Symbiosis and Nutrient Uptake

Mycorrhizal symbiosis is a fascinating and ecologically significant relationship between fungi and plant roots, playing a crucial role in nutrient uptake and cycling within ecosystems. This symbiotic association is particularly important in understanding how mushrooms and fungi contribute to the conversion of inorganic molecules into organic forms, a process vital for plant growth and soil health. In this mutualistic relationship, the fungus colonizes the plant's roots, forming an extensive network of filaments called hyphae, which greatly increases the surface area for absorption. This intricate network allows the fungus to access nutrients that might be otherwise unavailable to the plant.

The primary function of mycorrhizae is to enhance the host plant's ability to acquire nutrients, especially inorganic compounds, from the soil. Fungi are efficient absorbers of minerals and can take up nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and micronutrients, which are essential for plant growth. These inorganic molecules are then converted into organic forms through the fungus's metabolic processes. For instance, fungi can solubilize insoluble phosphorus compounds, making them accessible for plant uptake. This is achieved through the release of organic acids and enzymes that break down complex inorganic molecules, transforming them into simpler organic substances that can be easily absorbed by both the fungus and the plant.

The process of nutrient uptake in mycorrhizal symbiosis is highly efficient due to the large surface area provided by the fungal hyphae. These hyphae can explore the soil matrix more effectively than plant roots, reaching microscopic pores and depleting nutrient sources that would be inaccessible to roots alone. As the fungus absorbs inorganic nutrients, it benefits from the carbohydrates provided by the plant, which are products of photosynthesis. This exchange of resources highlights the mutualistic nature of the relationship, where both organisms gain essential resources they might struggle to obtain independently.

Furthermore, mycorrhizal fungi contribute to the long-term fertility of soils. By converting inorganic molecules into organic forms, they improve nutrient retention and reduce leaching. This is especially critical in ecosystems with nutrient-poor soils, where mycorrhizae can significantly enhance plant growth and ecosystem productivity. The organic compounds produced by the fungi also contribute to soil organic matter, which is essential for soil structure, water retention, and overall soil health.

In summary, mycorrhizal symbiosis is a key process in nutrient cycling, where fungi facilitate the conversion of inorganic molecules into organic forms, making them available to plants. This relationship not only benefits individual plants but also contributes to the overall health and productivity of ecosystems. Understanding these mechanisms provides valuable insights into sustainable agricultural practices and the potential for harnessing mycorrhizae to improve soil fertility and plant nutrition. The role of mushrooms and fungi in this process is a remarkable example of nature's ingenuity in nutrient management and ecosystem balance.

Easiest Way to Quarter Cremini Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Enzymatic Breakdown of Minerals by Fungi

Fungi, including mushrooms, play a crucial role in the biogeochemical cycling of nutrients by facilitating the conversion of inorganic molecules into organic forms. This process is primarily driven by the secretion of enzymes capable of breaking down complex minerals and rocks. Fungi produce a diverse array of enzymes, such as phosphatases, phosphatases, and siderophores, which target specific inorganic compounds like phosphates, sulfates, and iron. These enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis and chelation of minerals, making essential nutrients available for fungal metabolism and growth. This enzymatic activity is particularly significant in nutrient-poor environments, where fungi act as pioneers in mineral weathering and nutrient mobilization.

The enzymatic breakdown of minerals by fungi begins with the attachment of fungal hyphae to rock surfaces or mineral particles. Hyphae secrete organic acids, such as oxalic and citric acids, which dissolve mineral structures by chelating metal ions and lowering pH. Simultaneously, fungi release extracellular enzymes that further degrade mineral complexes. For example, acid phosphatases hydrolyze inorganic phosphates into organic phosphates, which can be directly assimilated by the fungus. This process not only benefits the fungus but also enriches the surrounding soil, making nutrients accessible to other organisms in the ecosystem.

One of the most well-studied mechanisms of mineral breakdown by fungi involves the use of siderophores, small molecules that bind and transport iron. In environments where iron is present in insoluble forms, fungi secrete siderophores to chelate ferric iron (Fe³⁺), converting it into a soluble and bioavailable form. Once bound to siderophores, iron is transported into fungal cells, where it is utilized in various metabolic processes, including photosynthesis and respiration. This ability to solubilize iron highlights the adaptability of fungi in nutrient acquisition and their role in enhancing soil fertility.

Fungal enzymes also contribute to the breakdown of silicate minerals, the most abundant minerals in Earth's crust. While this process is slower and less direct than the breakdown of phosphates or iron, fungi produce enzymes like polysaccharide monooxygenases and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases that can degrade the organic components of silicate matrices. Over time, this activity weakens mineral structures, facilitating further weathering by physical and chemical processes. The organic acids and chelating agents produced by fungi also aid in the dissolution of silicates, releasing cations like potassium, magnesium, and calcium into the soil.

The ecological significance of enzymatic mineral breakdown by fungi extends beyond nutrient cycling. By converting inorganic molecules into organic forms, fungi contribute to carbon sequestration, as organic matter produced by fungi becomes part of the soil carbon pool. Additionally, this process supports plant growth by improving soil structure and nutrient availability. Understanding the mechanisms of fungal mineral weathering is essential for applications in agriculture, bioremediation, and sustainable resource management, as fungi can be harnessed to enhance soil health and reclaim nutrient-depleted lands. In summary, the enzymatic breakdown of minerals by fungi is a vital process that bridges the gap between inorganic and organic matter, driving nutrient cycling and ecosystem productivity.

Grow Your Own Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Role of Mushrooms in Soil Organic Matter Formation

Mushrooms play a crucial role in soil organic matter formation through their unique ability to interact with both inorganic and organic components in the soil. While mushrooms themselves do not directly convert inorganic molecules into organic molecules through photosynthesis (as plants do), they contribute significantly to this process indirectly via their symbiotic relationships and decomposing activities. Mushrooms, as fungi, secrete enzymes that break down complex organic materials like dead plant matter, lignin, and cellulose, which are otherwise difficult to decompose. This decomposition process releases nutrients and simpler organic compounds, enriching the soil with organic matter.

One of the key mechanisms by which mushrooms contribute to soil organic matter formation is through their mycorrhizal associations with plants. Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing the plant’s ability to absorb nutrients, particularly inorganic compounds like phosphorus and nitrogen. In exchange, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. These carbohydrates are organic molecules that the fungus incorporates into its biomass and the surrounding soil, thereby increasing soil organic matter. This process effectively bridges the gap between inorganic and organic nutrient cycles in ecosystems.

Additionally, mushrooms act as primary decomposers in ecosystems, breaking down dead organic material into simpler forms. As they decompose plant and animal residues, they release organic compounds that contribute to the humus layer of the soil. Humus is a stable form of organic matter that improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability. By accelerating the decomposition process, mushrooms ensure that organic matter is continually recycled and replenished in the soil, fostering long-term soil fertility.

Another important role of mushrooms in soil organic matter formation is their involvement in nutrient cycling. Fungi can mobilize inorganic nutrients from minerals and rocks through a process called weathering. While this does not directly convert inorganic molecules into organic ones, it makes these nutrients available for plants and other organisms. Once absorbed by plants and converted into organic forms, these nutrients can re-enter the soil through litterfall and decomposition, further enriching organic matter. Mushrooms thus act as facilitators in the transformation and stabilization of organic matter in soil ecosystems.

Lastly, the extensive network of fungal hyphae (thread-like structures) created by mushrooms helps bind soil particles together, enhancing soil aggregation. This aggregation protects organic matter from rapid decomposition and erosion, allowing it to accumulate over time. The hyphae themselves also contribute to organic matter as they grow, die, and decompose, leaving behind organic residues. This dual role of mushrooms—as decomposers and soil stabilizers—makes them indispensable in the formation and maintenance of soil organic matter, ultimately supporting ecosystem health and productivity.

Carbs in Fried Mushroom Batter: What's the Count?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fungal Metabolism of Inorganic Compounds

Fungi, including mushrooms, play a significant role in the biogeochemical cycling of elements, and their ability to metabolize inorganic compounds is a fascinating aspect of their biology. This process is essential for nutrient acquisition and contributes to the overall ecosystem functioning. One of the key mechanisms through which fungi achieve this is by converting inorganic molecules into organic forms, a process driven by their unique metabolic capabilities.

Uptake and Transport of Inorganic Nutrients: Fungi have evolved efficient systems to acquire inorganic nutrients from their environment. They secrete various enzymes and organic acids that solubilize and mobilize essential elements. For instance, fungi can take up inorganic phosphorus by releasing phosphatases, which convert insoluble phosphorus compounds into soluble forms that can be easily absorbed. Similarly, they can access inorganic nitrogen sources by producing proteases and peptidases to break down complex organic matter, releasing ammonium and other nitrogenous compounds. This initial step of nutrient mobilization is crucial for the subsequent conversion into organic molecules.

Biotransformation of Inorganic Compounds: The metabolism of inorganic compounds by fungi involves a series of biochemical reactions. Once the inorganic nutrients are absorbed, they undergo transformation within the fungal cells. For example, inorganic sulfur can be oxidized to sulfate by fungal enzymes, which is then incorporated into organic compounds such as amino acids and vitamins. Fungi are also known to reduce inorganic compounds; they can reduce nitrate to ammonium, which is then assimilated into amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. This reduction process is particularly important in nitrogen metabolism.

Biosynthesis and Organic Compound Formation: The converted inorganic molecules are utilized in various biosynthetic pathways. Fungi can synthesize a wide array of organic compounds, including amino acids, nucleotides, and secondary metabolites. For instance, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, a central metabolic pathway, plays a crucial role in converting inorganic carbon (CO2) into organic intermediates, which are further used for the synthesis of complex molecules. Fungi also produce enzymes that catalyze the incorporation of inorganic elements into organic structures, ensuring the efficient utilization of resources.

Ecological Significance: The fungal metabolism of inorganic compounds has far-reaching implications in ecosystems. By converting inorganic molecules, fungi contribute to nutrient cycling, making essential elements available to other organisms. This process is particularly vital in nutrient-limited environments, where fungi act as primary decomposers and recyclers. Moreover, the organic compounds produced by fungi serve as a food source for other microorganisms and higher organisms, thus influencing the overall productivity and dynamics of ecosystems. Understanding these metabolic processes is essential for fields like mycology, ecology, and biotechnology, where fungal capabilities can be harnessed for various applications.

In summary, mushrooms and fungi, in general, possess remarkable metabolic versatility, allowing them to convert inorganic molecules into organic forms. This ability is fundamental to their survival and has a profound impact on nutrient cycling in ecosystems. The study of fungal metabolism provides valuable insights into the intricate relationships between microorganisms and their environment, offering potential applications in biotechnology and sustainable resource management. Further research in this area can lead to a better understanding of fungal contributions to global biogeochemical cycles.

Mushroom Magic: Do They Expire?

You may want to see also

Mushrooms and Carbon Sequestration Processes

Mushrooms play a significant role in carbon sequestration processes through their unique ability to interact with both inorganic and organic molecules in ecosystems. While mushrooms themselves do not directly convert inorganic carbon (such as carbon dioxide) into organic molecules like plants do through photosynthesis, they are integral to the carbon cycle in other ways. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, which primarily function as decomposers. Fungi secrete enzymes that break down complex organic matter, such as dead plant material, into simpler compounds. This process releases nutrients back into the soil, but it also involves the transformation and stabilization of carbon. As fungi decompose organic matter, they incorporate carbon into their hyphal networks, effectively storing it in the soil for extended periods.

The mycelium, the vegetative part of fungi, forms extensive underground networks that bind soil particles together, enhancing soil structure and carbon retention. This network acts as a carbon sink, trapping organic carbon compounds and preventing them from being released back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Additionally, mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, improve plant health and growth by facilitating nutrient uptake. Healthier plants can then photosynthesize more efficiently, converting more inorganic carbon dioxide into organic molecules and storing carbon in their tissues. Thus, while mushrooms do not directly convert inorganic molecules into organic ones, they indirectly support this process by fostering a healthier and more productive ecosystem.

Another critical aspect of mushrooms in carbon sequestration is their role in wood decay. Saprotrophic fungi, including those that produce mushrooms, break down lignin and cellulose in dead wood, which are complex organic molecules rich in carbon. During this decomposition, some carbon is released as carbon dioxide, but a significant portion is stabilized in the soil as humus or incorporated into fungal biomass. This long-term storage of carbon in soil and fungal structures contributes to reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Furthermore, the byproducts of fungal decomposition can enhance soil fertility, promoting the growth of more vegetation and thereby increasing the overall carbon storage capacity of the ecosystem.

Mushrooms also contribute to carbon sequestration through their involvement in the global phosphorus cycle. Fungi are efficient at mobilizing phosphorus from inorganic sources, making it available to plants. This nutrient cycling supports plant growth, which in turn drives greater carbon uptake from the atmosphere. By maintaining the health and productivity of forests and other ecosystems, mushrooms indirectly facilitate the conversion of inorganic carbon dioxide into organic molecules by plants. This interconnected process highlights the importance of fungi, and by extension mushrooms, in mitigating climate change.

In summary, while mushrooms do not directly convert inorganic molecules into organic molecules, they are vital to carbon sequestration processes through their roles as decomposers, soil stabilizers, and ecosystem supporters. Their ability to store carbon in soil, enhance plant growth, and decompose complex organic matter makes them key players in the global carbon cycle. Understanding and leveraging the functions of mushrooms and fungi can provide innovative solutions for carbon capture and storage, contributing to efforts to combat climate change.

Dehydrating Shiitake Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mushrooms, like other fungi, can convert inorganic molecules into organic molecules through a process called chemosynthesis, though they primarily rely on decomposing organic matter.

Mushrooms use enzymes and metabolic pathways to break down inorganic compounds, such as minerals and gases, and incorporate them into organic molecules like proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids.

Mushrooms can convert inorganic molecules like carbon dioxide, nitrogen compounds (e.g., ammonia or nitrates), and minerals (e.g., sulfur or phosphorus) into organic forms.

No, other organisms like certain bacteria, archaea, and plants (via photosynthesis) also convert inorganic molecules into organic molecules, but mushrooms play a unique role in nutrient cycling in ecosystems.

This process helps mushrooms recycle nutrients in ecosystems, making essential elements available to other organisms and contributing to soil fertility and plant growth.