Mushrooms, often perceived as simple organisms, are in fact complex multicellular fungi composed of numerous cells working together in a highly organized structure. Unlike single-celled organisms, mushrooms consist of specialized cell types, including hyphae—thread-like structures that form the bulk of the fungus—and cells that make up the cap, stem, and gills. These cells collaborate to perform essential functions such as nutrient absorption, growth, and reproduction. Understanding the multicellular nature of mushrooms not only highlights their biological sophistication but also sheds light on their ecological roles and potential applications in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cellular Structure | Mushrooms are multicellular organisms, composed of many cells. |

| Cell Type | Eukaryotic cells with a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. |

| Tissue Organization | Cells are organized into tissues, including hyphae (filamentous structures) and fruiting bodies. |

| Hyphal Structure | Hyphae are long, thread-like cells that form the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. |

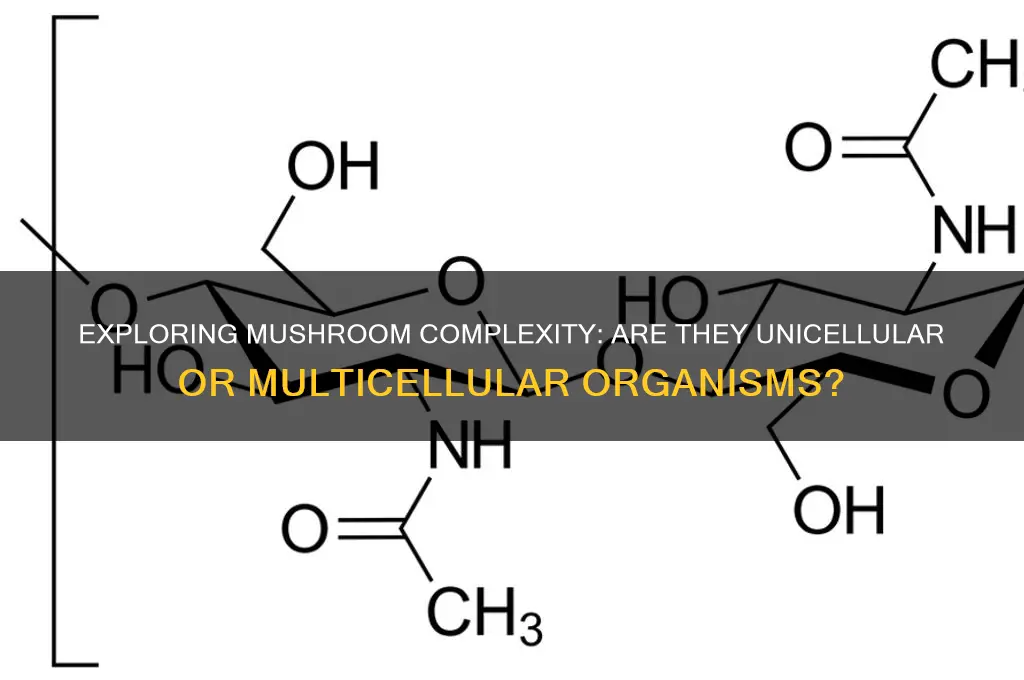

| Cell Walls | Composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides, providing structural support. |

| Multicellularity | Mushrooms exhibit complex multicellularity, with specialized cell types and tissue differentiation. |

| Growth Form | Grow through apical extension of hyphae and branching, forming a network of interconnected cells. |

| Reproduction | Can reproduce both asexually (via spores) and sexually (via fusion of hyphae and formation of fruiting bodies). |

| Size of Cells | Individual cells (hyphae) are typically microscopic, but the multicellular structure can be visible to the naked eye. |

| Complexity | Exhibit a high degree of cellular and tissue complexity compared to unicellular organisms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom Structure Basics: Mushrooms are multicellular fungi with specialized structures like hyphae, mycelium, and fruiting bodies

- Cell Types in Mushrooms: They contain vegetative cells (hyphae) and reproductive cells (spores) for growth and propagation

- Hyphal Networks: Hyphae form interconnected networks, enabling nutrient absorption and communication within the mushroom organism

- Fruiting Body Development: The visible mushroom (fruiting body) develops from mycelium to disperse spores

- Single vs. Multicellular: Mushrooms are multicellular, unlike single-celled organisms, with complex cellular organization for survival

Mushroom Structure Basics: Mushrooms are multicellular fungi with specialized structures like hyphae, mycelium, and fruiting bodies

Mushrooms are indeed multicellular organisms, belonging to the kingdom Fungi. Unlike single-celled organisms such as bacteria or yeast, mushrooms are composed of numerous cells that work together to form complex structures. These structures are essential for their growth, reproduction, and survival. The basic building blocks of mushrooms are specialized components like hyphae, mycelium, and fruiting bodies, each playing a distinct role in the fungus's life cycle. Understanding these structures is key to grasping how mushrooms function as multicellular organisms.

At the core of mushroom structure are hyphae, which are long, thread-like filaments that serve as the fundamental units of fungal growth. Hyphae are individual cells encased in a tubular structure, often compared to roots in plants. They grow by extending at their tips, allowing the fungus to explore and colonize new substrates. Hyphae are responsible for nutrient absorption, breaking down organic matter in the environment and extracting essential resources for the fungus. This network of hyphae forms the basis of the mushroom's multicellular nature, as they interconnect to create a larger, more complex system.

The collective mass of interconnected hyphae is known as mycelium, which acts as the vegetative part of the fungus. Mycelium can spread extensively underground or within its substrate, often covering large areas. It is through the mycelium that mushrooms absorb water, minerals, and other nutrients necessary for growth. The mycelium is not visible to the naked eye but is crucial for the fungus's survival and development. It is also the stage where the fungus spends most of its life cycle, remaining hidden until conditions are right for the formation of fruiting bodies.

Fruiting bodies are the most recognizable part of mushrooms, emerging above ground as the reproductive structures. These include the cap, gills, stem, and other features that produce and disperse spores. Fruiting bodies develop when environmental conditions, such as temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability, signal the mycelium to allocate resources to reproduction. Unlike the mycelium, which is multicellular and remains below the surface, fruiting bodies are transient structures that serve a specific purpose: to release spores and ensure the continuation of the species.

In summary, mushrooms are multicellular fungi with a sophisticated structure designed for growth, nutrient absorption, and reproduction. Hyphae form the basic cellular units, mycelium acts as the expansive, nutrient-gathering network, and fruiting bodies serve as the reproductive organs. Together, these specialized structures highlight the complexity of mushrooms as multicellular organisms, demonstrating their ability to thrive in diverse environments through coordinated cellular activity. Understanding these basics provides a foundation for exploring the fascinating biology of fungi.

Kosher Truffles: Are These Mushrooms Kosher or Not?

You may want to see also

Cell Types in Mushrooms: They contain vegetative cells (hyphae) and reproductive cells (spores) for growth and propagation

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are multicellular organisms composed of specialized cell types that facilitate their growth, survival, and reproduction. Unlike plants and animals, fungi have unique cellular structures adapted to their heterotrophic lifestyle. The primary cell types in mushrooms are vegetative cells, known as hyphae, and reproductive cells, called spores. These cells work in tandem to ensure the mushroom’s life cycle continues, from nutrient absorption to propagation. Understanding these cell types is essential to grasp how mushrooms function as complex, multicellular organisms.

Vegetative cells, or hyphae, form the bulk of a mushroom’s structure. Hyphae are long, thread-like filaments that grow and branch out to form a network called the mycelium. This mycelium acts as the mushroom’s body, absorbing nutrients from the environment through its extensive surface area. Hyphae are typically divided by cross-walls called septa, which contain pores allowing for the flow of nutrients and cellular components. However, some fungi have non-septate hyphae, where the cytoplasm flows continuously. These vegetative cells are responsible for the mushroom’s growth, nutrient uptake, and interaction with its surroundings, making them crucial for the organism’s survival.

In contrast to hyphae, reproductive cells, or spores, serve a different purpose. Spores are microscopic, single-celled structures produced by mushrooms for reproduction and dispersal. They are often generated in specialized structures like gills, pores, or teeth, depending on the mushroom species. Spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. When conditions are favorable, spores germinate and grow into new hyphae, starting the life cycle anew. This dual system of vegetative and reproductive cells ensures that mushrooms can both thrive in their current environment and colonize new areas.

The coexistence of hyphae and spores highlights the multicellular nature of mushrooms. Hyphae provide the foundation for growth and nutrient acquisition, while spores enable propagation and survival in diverse environments. This division of labor between cell types is a key feature of fungal biology, distinguishing mushrooms from single-celled organisms. Thus, mushrooms undeniably have more than one cell type, each with specific functions that contribute to the organism’s overall success.

In summary, mushrooms are multicellular organisms with two primary cell types: hyphae for vegetative growth and nutrient absorption, and spores for reproduction and dispersal. These cells work together to ensure the mushroom’s survival and propagation, showcasing the complexity of fungal life. By examining these cell types, it becomes clear that mushrooms are not simple, single-celled organisms but rather sophisticated structures with specialized roles for each cell. This understanding underscores the importance of recognizing the multicellular nature of mushrooms in discussions about their biology.

Mushroom Cap: The Ultimate Guide

You may want to see also

Hyphal Networks: Hyphae form interconnected networks, enabling nutrient absorption and communication within the mushroom organism

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are composed of multiple cells, and their structure is fundamentally based on a network of filamentous cells called hyphae. These hyphae are the building blocks of the fungal organism and form intricate, interconnected networks known as hyphal networks. This network is essential for the mushroom's survival, growth, and function, playing a critical role in nutrient absorption and communication within the organism. Unlike plants and animals, which have distinct organs for specific functions, fungi rely on their hyphal networks to perform multiple tasks simultaneously, making them highly efficient and adaptable organisms.

Hyphal networks are the primary means through which mushrooms absorb nutrients from their environment. Each hypha is surrounded by a cell wall and contains a plasma membrane that facilitates the uptake of water, minerals, and organic matter from the substrate, such as soil or decaying matter. The network's extensive surface area maximizes contact with the environment, allowing the mushroom to efficiently extract resources even from nutrient-poor surroundings. This absorptive capability is crucial for the mushroom's growth and development, as it relies on external sources for sustenance. The interconnected nature of the hyphae ensures that nutrients are distributed throughout the organism, supporting both the mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus) and the fruiting bodies (mushrooms) that emerge under favorable conditions.

Beyond nutrient absorption, hyphal networks also serve as a communication system within the mushroom organism. Hyphae are capable of transmitting chemical signals, electrical impulses, and even resources like carbohydrates and proteins between different parts of the network. This internal communication allows the fungus to respond to environmental changes, coordinate growth, and allocate resources efficiently. For example, if one part of the mycelium detects a rich nutrient source, it can signal other areas to redirect growth toward that location. This level of coordination is made possible by the continuous and dynamic nature of the hyphal network, which functions as a unified organism despite being composed of many individual cells.

The structure of hyphal networks is both flexible and resilient, enabling mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments. Hyphae can branch, fuse, and extend into new areas, allowing the network to grow and adapt to changing conditions. This plasticity is particularly important for fungi, which often inhabit unpredictable and resource-limited habitats. Additionally, the network's interconnectedness provides redundancy, ensuring that damage to one part of the mycelium does not necessarily compromise the entire organism. This resilience is a key factor in the success of fungi as a biological group, allowing them to colonize a wide range of ecosystems, from forest floors to deep-sea vents.

In summary, hyphal networks are the cornerstone of mushroom biology, enabling these multicellular organisms to absorb nutrients and communicate internally with remarkable efficiency. The interconnected nature of hyphae not only supports the mushroom's growth and survival but also highlights the unique and sophisticated organization of fungal life. Understanding hyphal networks provides valuable insights into the cellular complexity of mushrooms and underscores their role as more than just single-celled entities. Through their hyphal networks, mushrooms exemplify the power of cooperation and connectivity at the cellular level, making them a fascinating subject of study in biology.

The Intriguing World of Mushrooms: Single-Celled or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fruiting Body Development: The visible mushroom (fruiting body) develops from mycelium to disperse spores

The development of a mushroom's fruiting body is a fascinating process that begins with the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus consisting of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae are indeed multicellular, as each hypha is a long, tubular cell with multiple nuclei, challenging the notion that mushrooms are single-celled organisms. The mycelium grows through the substrate, such as soil or decaying wood, absorbing nutrients and establishing a robust network. When environmental conditions are favorable—typically involving factors like temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability—the mycelium initiates the formation of the fruiting body, the visible part of the mushroom we commonly recognize.

Fruiting body development starts with the aggregation of hyphae into a structure called the primordium, which serves as the foundation for the mushroom. This process is highly coordinated and involves cellular differentiation, where specific hyphae take on specialized roles. As the primordium grows, it develops into distinct parts: the stipe (stem), pileus (cap), and gills or pores, depending on the mushroom species. The gills or pores are particularly crucial, as they house the basidia, specialized cells that produce spores. This differentiation highlights the multicellular nature of mushrooms, as various cell types work together to form the fruiting body.

The primary purpose of the fruiting body is to facilitate spore dispersal, ensuring the fungus's survival and propagation. Spores are produced through meiosis in the basidia and are released into the environment when mature. This dispersal mechanism relies on the fruiting body's elevated structure, which aids in wind or animal-mediated spore distribution. The development of the fruiting body is thus a strategic investment by the mycelium to reproduce and colonize new areas, emphasizing the importance of multicellularity in fungi.

Environmental cues play a critical role in triggering fruiting body development. For example, changes in light exposure, carbon dioxide levels, or substrate exhaustion can signal the mycelium to initiate fruiting. This responsiveness to external conditions underscores the complexity of fungal biology and the coordinated effort of multiple cells. Once the fruiting body is fully developed, it releases spores, completing the life cycle and allowing the fungus to spread and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

In summary, the visible mushroom (fruiting body) develops from the multicellular mycelium as a means to disperse spores. This process involves cellular differentiation, environmental responsiveness, and the formation of specialized structures like gills or pores. By understanding fruiting body development, we gain insight into the intricate, multicellular nature of mushrooms and their adaptive strategies for survival and reproduction.

Sage and Mushrooms: A Match Made in Heaven?

You may want to see also

Single vs. Multicellular: Mushrooms are multicellular, unlike single-celled organisms, with complex cellular organization for survival

Mushrooms, often mistaken for simple organisms, are in fact multicellular fungi with a complex cellular structure that sets them apart from single-celled organisms. Unlike bacteria, protozoa, or yeast, which consist of a single cell, mushrooms are composed of numerous cells that work together in a highly organized manner. This multicellular nature allows mushrooms to perform specialized functions, such as nutrient absorption, growth, and reproduction, which are essential for their survival in diverse environments. The cellular complexity of mushrooms is a key factor in their ability to thrive in various ecosystems, from forest floors to decaying wood.

The distinction between single-celled and multicellular organisms is fundamental to understanding mushrooms' biology. Single-celled organisms, such as amoebas or paramecia, carry out all life processes within a single cell. In contrast, mushrooms exhibit cellular differentiation, where cells develop into specialized tissues and structures like mycelium, hyphae, and fruiting bodies. This differentiation enables mushrooms to efficiently extract nutrients from their surroundings, anchor themselves to substrates, and disperse spores for reproduction. The mycelium, a network of thread-like hyphae, is particularly crucial as it serves as the mushroom's primary means of nutrient absorption and growth.

One of the most striking features of mushrooms' multicellular organization is their ability to form fruiting bodies, the visible part of the fungus that emerges above ground. These structures are the result of coordinated cellular activity, where hyphae aggregate and differentiate into tissues such as the cap, stem, and gills. The gills, for instance, are densely packed with cells that produce and release spores, ensuring the mushroom's genetic continuity. This level of cellular cooperation and specialization is a hallmark of multicellular life and is absent in single-celled organisms, which rely solely on individual cellular functions.

The survival advantages of being multicellular are evident in mushrooms' adaptability and resilience. Their extensive mycelial networks can cover large areas, allowing them to access resources that single-celled organisms cannot reach. Additionally, the ability to form fruiting bodies enables mushrooms to disperse spores over long distances, increasing their chances of colonizing new habitats. This complexity also provides mushrooms with mechanisms to withstand environmental stresses, such as drought or predation, which single-celled organisms often lack. Thus, the multicellular nature of mushrooms is not just a structural feature but a critical adaptation for their ecological success.

In summary, mushrooms are multicellular organisms with a sophisticated cellular organization that contrasts sharply with single-celled life forms. Their ability to differentiate cells into specialized structures and tissues enables them to perform complex functions essential for survival and reproduction. This multicellularity is a key factor in mushrooms' ability to thrive in diverse environments, outcompeting single-celled organisms in many ecological niches. Understanding this distinction highlights the remarkable biology of mushrooms and their unique place in the natural world.

Magic Mushrooms: Understanding Psychoactive Fungi

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mushrooms are multicellular organisms, meaning they are composed of many cells that work together to form their structure.

Mushrooms have eukaryotic cells, which contain a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, similar to plant and animal cells.

No, different parts of a mushroom, such as the cap, stem, and gills, are made up of specialized cells that perform specific functions.

Mushroom cells lack chlorophyll and cell walls made of cellulose, unlike plant cells. Instead, their cell walls are primarily composed of chitin, a substance also found in insect exoskeletons.

Mushrooms begin their life cycle as a single-celled spore, but they must develop into a multicellular structure (the mycelium) before forming the visible mushroom (fruiting body).