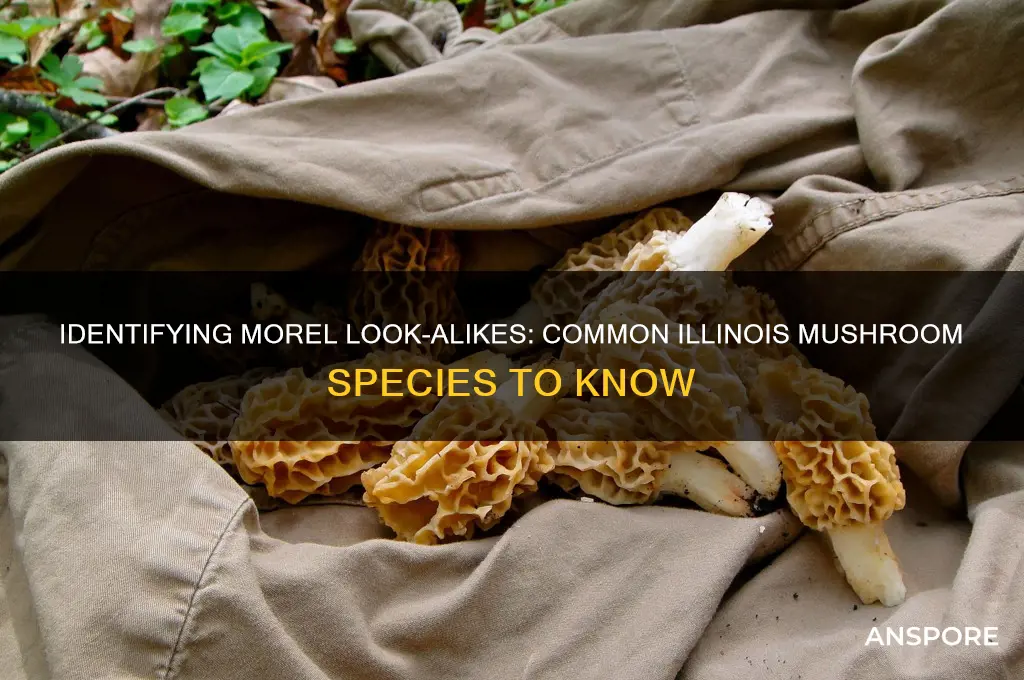

When foraging for morel mushrooms in Illinois, it’s crucial to be aware that several other mushroom species can resemble them, posing potential risks to inexperienced hunters. Mushrooms like the false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) and the early false morel (*Verpa bohemica*) share similar shapes and habitats but are toxic or require careful preparation. Additionally, some non-edible species, such as the wrinkled thimble cap (*Verpa conica*), can be mistaken for morels due to their conical caps and hollow stems. Proper identification is essential, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even fatalities. Always consult a field guide or an expert to ensure safe foraging.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| False Morel (Gyromitra spp.) | Brain-like or wrinkled cap, often reddish-brown, lacks the honeycomb appearance of true morels |

| Elf Cup (Sarcoscypha spp.) | Bright red cup-shaped fungus, grows on wood, much smaller than morels |

| Wrinkled Peach (Rhodotus palmatus) | Fan-shaped or peachy cap with wrinkles, pinkish to reddish-brown, grows on wood |

| Verpa bohemica (Thimble Morel) | Smooth, thimble-like cap, skirt-like cup at the base of the stem, lacks true morel's honeycomb texture |

| Pholiota squarrosa (Scaly Pholiota) | Scaly, conical cap, grows in clusters on wood, yellowish-brown |

| Stinkhorn (Phallus ravenelii) | Phallic shape, foul odor, slimy spore mass on the cap, not similar to morels in appearance |

| Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) | Fan-shaped, shell-like cap, grows on wood, lacks honeycomb texture |

| Dryad's Saddle (Cerioporus squamosus) | Large, brown, scaly cap with a saddle-like shape, grows on wood, not honeycomb-textured |

| Split Gill (Schizophyllum commune) | Fan-shaped, split gills, grows on wood, lacks morel's honeycomb pattern |

| Note: Always consult a local mycologist or field guide for accurate identification, as some false morels can be toxic. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- False Morels: Gyromitra species resemble morels but are toxic, requiring careful identification to avoid poisoning

- Elf Cup Mushrooms: Orange peel-like fungi often mistaken for morels due to similar color and shape

- Wrinkled Ink Caps: Dark, wrinkled caps can mimic morels but are a different species entirely

- Split Gill Mushrooms: Shaggy, split gills may appear morel-like but are not edible or safe

- Coral Mushrooms: Branching, coral-like structures can be confused with morels but are distinct in texture

False Morels: Gyromitra species resemble morels but are toxic, requiring careful identification to avoid poisoning

Gyromitra species, commonly known as false morels, are a deceptive doppelgänger to the prized morel mushrooms. At first glance, their brain-like, wrinkled caps and hollow stems might fool even seasoned foragers. However, these mushrooms harbor a dangerous secret: they contain gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine, a compound used in rocket fuel. Ingesting false morels can lead to symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to seizures, and in severe cases, organ failure or death. While cooking reduces the toxin levels, it does not eliminate the risk entirely, making accurate identification critical.

To distinguish false morels from true morels, examine the cap structure. True morels have a honeycomb-like appearance with distinct pits and ridges, while false morels have a more convoluted, brain-like surface. Additionally, true morels are typically hollow throughout, whereas false morels may have cottony or partially solid interiors. Another telltale sign is the stem: false morels often have a thicker, more substantial stem compared to the delicate, hollow stem of true morels. If in doubt, avoid harvesting the mushroom altogether, as the consequences of misidentification can be severe.

Foraging safely requires more than visual inspection. False morels are particularly treacherous because their toxicity can vary depending on factors like location, age, and preparation methods. Even experienced foragers have fallen victim to their resemblance to true morels. To minimize risk, carry a reliable field guide or consult a mycologist when identifying mushrooms. If you suspect you’ve ingested false morels, seek medical attention immediately, as prompt treatment can mitigate the effects of poisoning.

Despite their toxic nature, Gyromitra species are not without intrigue. Some cultures have traditionally consumed them after extensive preparation, such as boiling and discarding the water multiple times. However, this practice is not recommended, as it does not guarantee complete toxin removal. Instead, focus on cultivating a deep understanding of mushroom morphology and habitat. True morels thrive in specific environments, such as disturbed soil near trees, while false morels are often found in coniferous forests. Knowing these preferences can further aid in accurate identification.

In the world of mushroom foraging, caution is paramount. False morels serve as a stark reminder that nature’s beauty can sometimes conceal danger. By mastering the subtle differences between these species, foragers can safely enjoy the bounty of the forest while avoiding the pitfalls of toxic look-alikes. Remember, when it comes to mushrooms, certainty is the only acceptable standard—doubt should always lead to abstention.

Spotting Tree Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Elf Cup Mushrooms: Orange peel-like fungi often mistaken for morels due to similar color and shape

Elf Cup mushrooms, scientifically known as *Sarcoscypha coccinea*, are a striking sight in Illinois forests, often catching the eye with their vibrant, orange peel-like appearance. These fungi thrive in deciduous woods, particularly on decaying wood or twigs, and their cup-shaped structure can easily be mistaken for the prized morel mushroom by novice foragers. The key similarity lies in their color and shape: both Elf Cups and morels often display hues of orange or brown, and their cup-like forms can appear deceptively alike from a distance. However, a closer inspection reveals critical differences that every forager should know.

To distinguish Elf Cups from morels, focus on their texture and structure. Elf Cups have a smooth, gelatinous exterior that feels almost rubbery to the touch, whereas morels are characterized by their spongy, honeycomb-like ridges. Additionally, Elf Cups are significantly smaller, typically measuring less than an inch in diameter, compared to morels, which can grow several inches tall. Foraging tip: always carry a magnifying glass or a small knife to examine the mushroom’s surface and underside, as these details are crucial for accurate identification.

While Elf Cups are not toxic, they are not considered edible due to their tough, unpalatable texture. This is another point of differentiation from morels, which are highly sought after for their culinary value. If you’re foraging in Illinois and come across an orange, cup-shaped fungus, take a moment to assess its features before assuming it’s a morel. Misidentification can lead to disappointment in the kitchen or, worse, accidental ingestion of a harmful species. Always prioritize safety by cross-referencing with a reliable field guide or consulting an experienced mycologist.

For those interested in observing Elf Cups in their natural habitat, late winter to early spring is the ideal time to explore Illinois woodlands. Look for them on fallen branches or stumps, often in clusters that resemble scattered orange peels. While they may not be a culinary treasure, Elf Cups offer a unique aesthetic appeal and serve as a reminder of the diverse fungal ecosystem in the region. By learning to identify them correctly, foragers can deepen their appreciation for the natural world while avoiding common pitfalls in mushroom hunting.

Mushroom Varieties: A Diverse and Delicious World

You may want to see also

Wrinkled Ink Caps: Dark, wrinkled caps can mimic morels but are a different species entirely

In the forests of Illinois, foragers often mistake Wrinkled Ink Caps (*Coprinus comatus*) for morels due to their dark, wrinkled caps. These mushrooms emerge in a similar habitat—wooded areas or disturbed soils—and their textured appearance can deceive even seasoned hunters. However, unlike morels, Wrinkled Ink Caps belong to the *Coprinus* genus, known for their delicate, short-lived nature. Their caps start as egg-like structures before unfurling into bell shapes, eventually dissolving into a black, inky liquid—a unique trait morels lack.

To distinguish Wrinkled Ink Caps from morels, focus on key features. Morels have a honeycomb-like, spongy cap with pits and ridges, while Wrinkled Ink Caps have gills beneath their wrinkled surface. Additionally, morels grow from a hollow stem, whereas Wrinkled Ink Caps have a slender, fibrous stem that often resembles a small tree trunk. A simple test: slice a cap open. If you see gills, it’s an Ink Cap, not a morel. This quick identification saves time and prevents accidental consumption, as Ink Caps are edible but must be cooked promptly to avoid their autodigestion process.

Foraging safely requires attention to detail. Wrinkled Ink Caps are edible when young, but their rapid decay makes timing crucial. Harvest them before the cap begins to flatten and darken, and cook within hours to preserve their mild, nutty flavor. Morels, on the other hand, remain firm and stable for days. Always carry a field guide or use a mushroom identification app to cross-reference findings. Misidentification can lead to toxic ingestion, as some look-alikes, like *Verpa bohemica*, resemble both morels and Ink Caps but are less desirable or even harmful.

Instruct novice foragers to start by learning the life cycles of both species. Wrinkled Ink Caps progress from egg-like to inky decay in days, while morels maintain their structure throughout their lifespan. Practice by comparing fresh specimens side by side, noting differences in texture, color, and stem structure. Foraging workshops or local mycological clubs in Illinois can provide hands-on experience. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms but to understand their unique characteristics, ensuring a safe and rewarding harvest.

Did Mushrooms Originate from Outer Space? Exploring the Cosmic Fungus Theory

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Split Gill Mushrooms: Shaggy, split gills may appear morel-like but are not edible or safe

In the forests of Illinois, foragers often encounter mushrooms with shaggy, split gills that resemble morels at first glance. Split Gill mushrooms, scientifically known as *Schizophyllum commune*, share a similar texture and color palette with morels, making them a common source of confusion. However, unlike morels, Split Gills are not edible and can cause gastrointestinal distress if consumed. Their gills, which split longitudinally as they mature, create a visually striking but deceptive appearance that lures even experienced hunters.

To distinguish Split Gills from morels, focus on their growth pattern and gill structure. Split Gills typically grow in clusters on decaying wood, whereas morels emerge singly or in small groups from forest floors. The gills of Split Gills are thin, wavy, and distinctly split, whereas morels have a honeycomb-like network of ridges and pits. Additionally, Split Gills lack the hollow stem characteristic of morels. If you’re unsure, avoid harvesting—misidentification can lead to unpleasant or even harmful outcomes.

From a safety perspective, consuming Split Gills is not recommended, even in small quantities. While they are not fatally toxic, they can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in sensitive individuals. Foragers, especially beginners, should prioritize learning the subtle differences between these mushrooms and morels. Carrying a field guide or using a mushroom identification app can provide real-time assistance during foraging expeditions. Always remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

A comparative analysis highlights the importance of texture and habitat in mushroom identification. While Split Gills and morels share a shaggy appearance, their ecological niches differ significantly. Split Gills are saprotrophic, breaking down dead wood, while morels are often associated with living trees or disturbed soil. This distinction underscores the need to consider both visual and environmental cues when foraging. By mastering these differences, enthusiasts can safely enjoy the thrill of mushroom hunting without risking their health.

Practically, foragers in Illinois should adopt a cautious approach when encountering mushrooms with split or shaggy features. Start by examining the substrate—Split Gills will always be found on wood, while morels are terrestrial. Next, inspect the gills or ridges closely; the longitudinal splits of Split Gills are a dead giveaway. Finally, avoid relying solely on color or overall shape, as these can vary widely within species. With patience and practice, distinguishing between Split Gills and morels becomes second nature, ensuring a safe and rewarding foraging experience.

Mastering the Art of Cleaning Rams Head Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Coral Mushrooms: Branching, coral-like structures can be confused with morels but are distinct in texture

Coral mushrooms, with their intricate, branching structures, often catch the eye of foragers exploring Illinois woodlands. At first glance, their upright, fork-like formations might remind you of morels, especially if you’re scanning the forest floor for those prized honeycomb caps. However, a closer inspection reveals a critical difference: texture. While morels are spongy and riddled with pits and ridges, coral mushrooms are smoother, almost brittle, and lack the honeycomb pattern. This distinction is crucial, as misidentification can lead to unpleasant—or even dangerous—consequences.

To avoid confusion, focus on the mushroom’s base. Coral mushrooms typically grow from a central, often thick, stem that branches outward, resembling underwater coral. In contrast, morels have a more hollow, conical structure with a seamless connection to the stem. Additionally, coral mushrooms come in vibrant hues like yellow, orange, or white, whereas morels are typically brown or tan. If you’re unsure, gently press the mushroom’s surface: coral mushrooms will feel firmer, almost waxy, compared to the soft, sponge-like texture of morels.

Foraging safely requires more than visual identification. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to cross-reference your findings. If you’re new to foraging, consider joining a local mycological club or attending a guided mushroom walk in Illinois. These resources can provide hands-on experience and expert advice, reducing the risk of misidentification. Remember, while coral mushrooms are generally not toxic, some species can cause gastrointestinal discomfort if consumed, so caution is key.

One practical tip for distinguishing between the two is to examine the mushroom’s underside. Morels have their spores housed in the honeycomb network of their caps, while coral mushrooms produce spores on their branching surfaces. This difference in spore-bearing structures is a telltale sign that can help even novice foragers make an accurate identification. By focusing on these specific traits, you’ll develop a sharper eye for the unique characteristics that set coral mushrooms apart from morels.

In conclusion, while coral mushrooms may initially resemble morels due to their branching structure, their distinct texture and other features make them easy to differentiate with practice. Always prioritize safety by double-checking your findings and avoiding consumption unless you’re absolutely certain. With patience and knowledge, you’ll soon be able to appreciate coral mushrooms for their beauty and uniqueness, rather than mistaking them for their more coveted counterparts.

Do Flower Boots Work on Glowing Mushrooms? A Myth-Busting Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, several mushrooms in Illinois resemble morels, such as false morels (Gyromitra species) and early false morels (Verpa bohemica). These look-alikes can be toxic and should not be consumed.

True morels have a honeycomb-like cap with pits and ridges, while false morels have a brain-like, wrinkled appearance. Additionally, true morels are hollow throughout, whereas false morels are often partially filled with cotton-like material.

Yes, false morels and some species of the genus Gyromitra are poisonous and can resemble morels. It’s crucial to properly identify mushrooms before consuming them, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death.