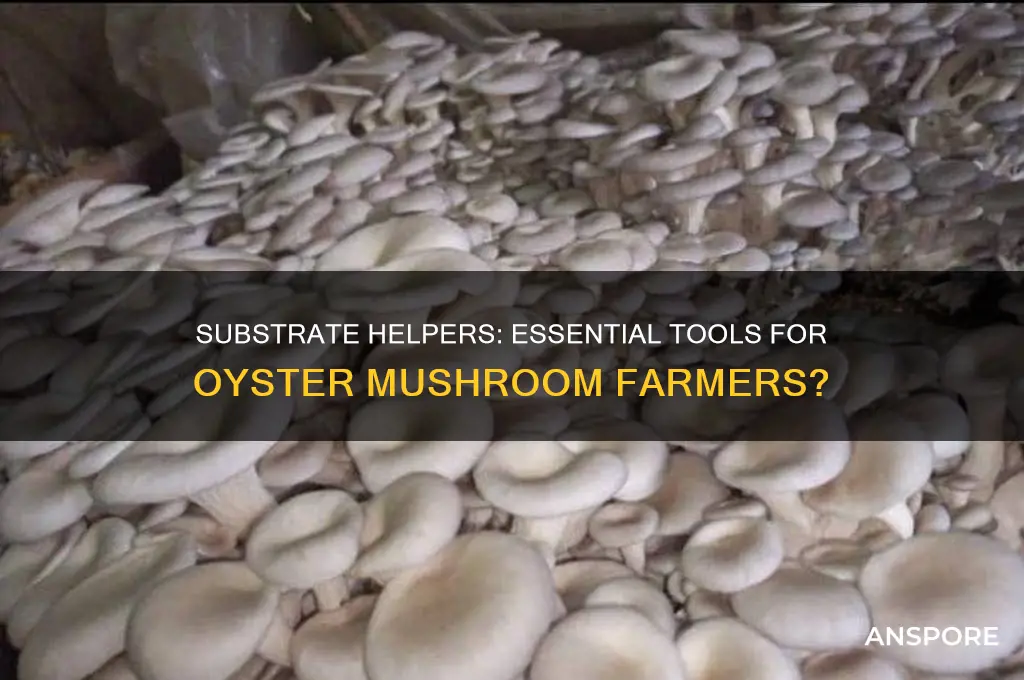

Oyster mushroom cultivation often involves the use of a substrate helper, which is a material added to the growing medium to enhance mycelium growth and fruiting body production. Substrate helpers, such as straw, sawdust, or coffee grounds, provide essential nutrients and structure for the mushrooms to thrive. Farmers carefully select and prepare these materials to create an optimal environment for oyster mushrooms, ensuring a successful and bountiful harvest. The choice of substrate helper can significantly impact the quality and yield of the crop, making it a crucial aspect of the cultivation process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Substrate Helper Usage | Yes, many oyster mushroom farmers use substrate helpers to enhance growth and yield. |

| Common Substrate Helpers | Straw, sawdust, coffee grounds, wood chips, and agricultural waste. |

| Purpose | Provides a nutrient-rich base for mycelium colonization and mushroom fruiting. |

| Benefits | Improves mushroom yield, accelerates growth, and reduces contamination risk. |

| Preparation | Substrates are often pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing organisms. |

| Supplementation | Some farmers add supplements like gypsum, lime, or bran to optimize nutrient content. |

| Environmental Impact | Utilizes agricultural and industrial waste, promoting sustainability. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Reduces costs by using readily available and often recycled materials. |

| Common Challenges | Maintaining proper moisture and pH levels, preventing contamination. |

| Popular Techniques | Straw logs, sawdust blocks, and bag cultivation methods. |

Explore related products

$22.31 $23.99

What You'll Learn

Types of Substrate Helpers

Oyster mushroom farmers often rely on substrate helpers to optimize growth, yield, and quality. These additives enhance the nutritional and structural properties of the substrate, creating an ideal environment for mycelium colonization. From natural supplements to chemical amendments, the types of substrate helpers vary widely, each offering unique benefits and considerations.

Organic Amendments: Boosting Nutrient Content Naturally

One popular category of substrate helpers is organic amendments, such as wheat bran, soybean meal, or cottonseed hulls. These materials are rich in nitrogen and other essential nutrients, accelerating mycelium growth. For instance, adding 5–10% wheat bran by weight to straw substrates can significantly improve mushroom yields. Farmers often prefer these options for their sustainability and compatibility with organic farming practices. However, balancing the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is critical; excessive nitrogen can lead to contamination or poor fruiting.

Gypsum: A Structural and Nutritional Enhancer

Gypsum (calcium sulfate) is a versatile substrate helper used to improve substrate structure and provide calcium, a vital nutrient for mushroom development. Typically applied at a rate of 1–2% by weight, gypsum helps prevent substrate compaction, allowing better air circulation and water retention. Its calcium content also strengthens mushroom cell walls, enhancing shelf life and texture. While gypsum is widely used, over-application can raise substrate pH, potentially inhibiting mycelium growth.

Chemical Additives: Precision with Caution

For farmers seeking precise control, chemical additives like lime or hydrogen peroxide serve as substrate helpers. Lime, applied at 1–2% by weight, adjusts pH levels, creating an optimal range (6.0–6.5) for oyster mushrooms. Hydrogen peroxide, used in diluted form (3% solution), sterilizes substrates, reducing the risk of contamination. These additives require careful measurement and application, as misuse can harm mycelium or produce unsafe mushrooms. They are particularly useful in large-scale operations where consistency is paramount.

Microbial Inoculants: Harnessing Beneficial Bacteria

An emerging trend is the use of microbial inoculants, such as *Trichoderma* species, as substrate helpers. These beneficial microorganisms outcompete harmful pathogens, reducing contamination risks. Applied as a liquid spray or mixed into the substrate, they create a protective biofilm around the mycelium. While research is ongoing, early results suggest improved yields and disease resistance. Farmers adopting this method should source inoculants from reputable suppliers to ensure efficacy and safety.

Understanding the types of substrate helpers allows oyster mushroom farmers to tailor their approach to specific needs, whether prioritizing organic practices, structural integrity, contamination control, or yield maximization. Each option comes with its own set of advantages and challenges, making informed decision-making essential for success.

Do Mushrooms Require High Nitrogen Levels for Growth and Health?

You may want to see also

Benefits of Using Substrate Helpers

Oyster mushroom farmers often turn to substrate helpers to optimize their yields and streamline their operations. These additives, which can include supplements like gypsum, limestone, or agricultural by-products, play a crucial role in enhancing the nutritional content and structure of the growing medium. By incorporating substrate helpers, farmers can create an ideal environment for mycelium colonization, leading to faster growth and more robust mushroom production.

One of the primary benefits of using substrate helpers is their ability to balance pH levels in the growing medium. Oyster mushrooms thrive in slightly acidic to neutral conditions, typically between pH 5.5 and 7.0. Gypsum, for instance, can be added at a rate of 1-2% by weight to stabilize pH and provide essential calcium and sulfur. This not only ensures optimal nutrient availability but also prevents the substrate from becoming too acidic, which can inhibit mycelium growth. Farmers should monitor pH levels regularly using a soil testing kit to fine-tune their substrate mixtures.

Another advantage of substrate helpers is their role in improving substrate structure and aeration. Materials like straw, sawdust, or coffee grounds, when combined with helpers like bran or cottonseed meal, create a more porous medium. This allows for better air circulation, which is critical for mycelium respiration and fruitbody formation. For example, adding 5-10% cottonseed meal by weight can increase the substrate’s water-holding capacity while maintaining adequate airflow. Proper aeration reduces the risk of contamination and promotes even mushroom development.

From an economic perspective, substrate helpers can significantly reduce production costs and increase profitability. By enhancing nutrient availability and accelerating colonization, farmers can achieve higher yields in shorter time frames. For instance, supplementing straw substrates with 10-15% wheat bran can boost mushroom production by up to 30%. Additionally, reusing substrates with the help of additives like lime or gypsum extends their lifespan, minimizing waste and resource consumption. This makes substrate helpers a sustainable and cost-effective solution for both small-scale and commercial growers.

Lastly, substrate helpers contribute to disease resistance and overall crop health. Certain additives, such as limestone or wood ash, create an environment less favorable to competing molds and bacteria. Applying limestone at a rate of 1-2% by weight can deter pathogens by maintaining optimal pH levels. Similarly, incorporating biological agents like *Trichoderma* species alongside substrate helpers can further protect the crop from common fungal diseases. By fortifying the substrate, farmers can reduce the need for chemical interventions and ensure a healthier, more consistent harvest.

Do Mushrooms Use Serotonin? Unveiling the Fungal Brain Connection

You may want to see also

Common Materials for Substrate Helpers

Oyster mushroom farmers often rely on substrate helpers to optimize growth, enhance yield, and ensure consistent quality. These additives improve nutrient availability, moisture retention, and structural integrity of the growing medium. Common materials for substrate helpers include agricultural byproducts, natural supplements, and microbial inoculants, each serving a specific function in the cultivation process.

Agricultural Byproducts: The Backbone of Substrate Helpers

Straw, sawdust, and corn cobs are staple materials in oyster mushroom cultivation, but they often require supplementation. Wheat bran, for instance, is a popular substrate helper due to its high nutrient content. Adding 5–10% wheat bran by weight to the substrate increases nitrogen levels, promoting faster mycelial colonization. Similarly, cottonseed hulls improve moisture retention, reducing the need for frequent watering. These byproducts are cost-effective and widely available, making them ideal for small-scale and commercial growers alike.

Natural Supplements: Boosting Nutrient Profiles

Gypsum (calcium sulfate) is a critical substrate helper, providing calcium and sulfur essential for mushroom development. A dosage of 1–2% gypsum by substrate weight prevents structural abnormalities in fruiting bodies. Another natural additive, limestone, balances pH levels, ensuring the substrate remains within the optimal range of 6.0–6.5. For organic growers, alfalfa meal offers a rich source of nitrogen, vitamins, and trace minerals, enhancing both yield and mushroom quality.

Microbial Inoculants: The Hidden Catalysts

Beneficial microorganisms, such as *Trichoderma* species, are increasingly used as substrate helpers to suppress pathogens and improve nutrient breakdown. These biocontrol agents are typically applied at a rate of 1–2 grams per kilogram of substrate. Another microbial helper, effective microorganisms (EM), enhances fermentation in pasteurized substrates, accelerating the decomposition process. While microbial inoculants require precise application to avoid contamination, they offer a sustainable solution for disease management and nutrient cycling.

Practical Tips for Effective Use

When incorporating substrate helpers, uniformity is key. Mix additives thoroughly to ensure even distribution throughout the substrate. Always pasteurize or sterilize substrates before adding microbial inoculants to eliminate competing organisms. Monitor moisture levels closely, as some helpers, like gypsum, can affect water retention. Lastly, experiment with small batches to determine the optimal combination of materials for your specific growing conditions.

By strategically selecting and applying these common materials, oyster mushroom farmers can create a substrate environment that fosters robust growth and maximizes productivity.

Prince and Psilocybin: Unraveling the Mushroom Mystery in His Life

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Application Techniques for Substrate Helpers

Oyster mushroom farmers often rely on substrate helpers to optimize growth, enhance yields, and improve mushroom quality. These additives, ranging from agricultural byproducts to microbial inoculants, play a critical role in creating an ideal environment for mycelium colonization. However, their effectiveness hinges on precise application techniques tailored to the substrate type, mushroom strain, and environmental conditions.

Layering and Mixing: A Comparative Approach

Two primary methods dominate substrate helper application: layering and thorough mixing. Layering involves sprinkling the helper (e.g., gypsum or limestone) between substrate layers, ensuring even distribution without over-concentration. This method is ideal for coarse substrates like straw, where uniform coverage is challenging. Mixing, on the other hand, blends the helper directly into the substrate, often during pasteurization or hydration. For fine substrates like sawdust, mixing guarantees consistent nutrient availability but requires careful measurement—typically 1–2% by weight of the substrate. For instance, adding 100 grams of gypsum per 10 kilograms of sawdust can improve calcium levels, essential for oyster mushroom fruiting.

Hydration and Activation: Timing Matters

Some substrate helpers, such as microbial inoculants or enzymes, require activation through hydration. These additives are often applied during the substrate soaking phase, allowing them to disperse evenly. For example, Trichoderma-based products, used to suppress contaminants, are mixed into water at a rate of 1 gram per liter, then soaked with the substrate for 1–2 hours before pasteurization. This ensures the microbes colonize the substrate before mushroom mycelium is introduced. Overlooking hydration timing can render these helpers ineffective, as they may not survive the pasteurization process or compete poorly with mycelium.

Spraying and Drenching: Targeted Applications

For substrates already colonized by mycelium, spraying or drenching substrate helpers offers a non-invasive solution. This technique is particularly useful for liquid additives like humic acid or kelp extracts, which stimulate mycelial growth during the fruiting stage. A foliar spray of 0.5% kelp solution applied during pinning can enhance mushroom size and color. Drenching, where the helper is poured directly onto the substrate, is effective for water-soluble nutrients like phosphorus supplements, applied at a rate of 5 ml per liter of water. Caution is advised to avoid over-saturation, which can lead to anaerobic conditions and contamination.

Cautions and Troubleshooting

While substrate helpers are beneficial, improper application can backfire. Overuse of lime, for instance, can raise substrate pH above 7.5, inhibiting mycelial growth. Similarly, excessive microbial inoculants may compete with mushroom mycelium for resources. Farmers should monitor substrate pH, moisture, and temperature post-application, adjusting dosages based on observable effects. For example, if yellowing occurs after gypsum application, reduce the dosage by 50% in the next batch. Always test new helpers on a small scale before full implementation to avoid crop loss.

Mastering substrate helper application techniques requires a blend of science and observation. Whether layering, mixing, hydrating, or spraying, the goal is to create a harmonious environment where mycelium thrives. By adhering to recommended dosages, timing applications strategically, and monitoring outcomes, oyster mushroom farmers can maximize the benefits of these additives, ensuring healthier crops and higher yields.

Do Mushrooms Absorb CO2? Exploring Their Role in Carbon Cycling

You may want to see also

Cost-Effectiveness of Substrate Helpers

Oyster mushroom farmers often turn to substrate helpers to optimize their yields, but the cost-effectiveness of these additives is a critical consideration. Substrate helpers, such as gypsum, lime, or supplements like bran or cottonseed meal, are used to enhance the nutritional profile and structure of the growing medium. While they can improve mushroom productivity, their financial impact varies depending on the scale of operation, type of helper, and local availability. For small-scale growers, the added cost may outweigh the benefits, whereas larger farms might find the investment justifiable due to increased yields.

Analyzing the cost-effectiveness requires a breakdown of expenses versus returns. For instance, gypsum, a common substrate helper, typically costs $0.10 to $0.20 per pound and is applied at a rate of 1-2% of the substrate weight. If a 100-pound substrate batch yields an additional 5-10 pounds of mushrooms due to gypsum, the added revenue must exceed the $1-$2 spent on the helper. However, this calculation assumes consistent results, which can vary based on environmental factors and farming practices. Growers must also consider the labor and time involved in mixing and applying these additives.

A persuasive argument for substrate helpers lies in their long-term benefits. For example, lime not only improves substrate pH but also reduces the risk of contamination, potentially saving costs associated with failed batches. Similarly, supplements like soybean meal, priced at $0.30 to $0.50 per pound, can significantly boost protein content in the substrate, leading to larger, more robust mushrooms. While the upfront cost is higher, the increased market value of premium mushrooms can offset expenses. This approach is particularly appealing for specialty mushroom growers targeting high-end markets.

Comparatively, organic substrate helpers like straw or wood chips are often more cost-effective for beginners. These materials are inexpensive and readily available, though they may require additional preparation, such as pasteurization. For instance, pasteurizing straw using a hot water bath costs approximately $0.05 per pound but ensures a sterile substrate, reducing contamination risks. While this method demands more labor, it aligns with organic farming principles and can appeal to eco-conscious consumers, potentially commanding higher prices.

In conclusion, the cost-effectiveness of substrate helpers hinges on a grower’s specific goals, resources, and market position. Small-scale farmers may prioritize low-cost, labor-intensive methods, while commercial operations might invest in premium additives for maximum yield. Practical tips include starting with small-scale trials to measure impact, sourcing local materials to reduce costs, and calculating break-even points for each helper. By balancing initial expenses with potential returns, oyster mushroom farmers can make informed decisions that align with their financial and production objectives.

Do Mushrooms Absorb or Produce Vitamins? Unveiling Their Nutritional Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A substrate helper is an additive or material used to improve the structure, nutrient content, or moisture retention of the growing medium (substrate) for oyster mushrooms. Common examples include gypsum, lime, or agricultural waste like straw or sawdust.

No, the use of a substrate helper depends on the substrate type and farming goals. Some substrates, like straw, may require helpers to enhance structure or nutrition, while others, like sawdust, might not need additional additives.

Substrate helpers can improve mushroom yield, speed up colonization, enhance nutrient availability, and optimize moisture retention. They also help prevent contamination and ensure a more consistent growing environment.